Healthcare reform is an important topic in presidential campaigns and it is on the agenda in many statehouses across the nation. However, before moving forward with reforms and new options, it is important to analyze where we are at, specifically how the Affordable Care Act (ACA) is working.

In 1934, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt considered including national healthcare in the New Deal, but ultimately omitted it, fearing political pushback on other program proposals, such as Social Security and unemployment insurance. Efforts by each administration thereafter were similarly thwarted until 1965, when President Lyndon Johnson pushed Congress to pass legislation that created Medicaid and Medicare. Even after Medicaid and Medicare, significant healthcare reform continued to be a political third rail that often went nowhere, as evidenced by President Bill Clinton’s failed effort in 1993 to establish a national health insurance program.

All that changed, however, when in 2010 President Barack Obama signed into law the ACA, commonly known as “Obamacare,” a healthcare reform package designed to increase access to and the affordability of quality health insurance plans. However, President Obama’s legislative success played a key role that ultimately cost his party at the ballot box later that year when Congress flipped from Democrat- to Republican-controlled. Long-term though, benefits in the ACA have proven popular among the electorate.

As a new data dashboard by the Rockefeller Institute of Government illustrates, more people across the nation now have health insurance than ever before. Prior to the ACA, more than 15 percent of the United States population did not have health insurance; in fewer than eight years, the percentage of uninsured Americans dropped by almost half, to 8.7 percent.

But, given that the implementation of the ACA was largely left to states, success in reducing the rate of the uninsured varies from state to state. An important 2017 study by the Rockefeller Institute of Government, Texas A&M, Brookings Institution, and Wake Forest University, analyzed five diverse states — California, Michigan, Florida, North Carolina, and Texas — to see how each was implementing the ACA. California and Michigan aggressively implemented the ACA, while Florida, North Carolina, and Texas, states with a general opposition to the law, did not.

Using the Rockefeller Institute data dashboard to see how those five states are doing today, we found that supportive states, California and Michigan, have done a better job reducing the percentage of uninsured in their states versus the “oppositional” states, Florida, North Carolina, and Texas (see Table 1). California and Michigan reduced the number of uninsured at nearly twice the rate of Florida, North Carolina, and Texas; and Florida and Texas still have double-digit uninsured rates in their states.

TABLE 1. Change in Uninsured Rate in Five Key States

| State | ACA Expansion | 2010 Uninsured Rate | 2017 Uninsured Rate | Change |

| California | Created state health exchange; expanded Medicaid | 16% | 6% | -63% |

| Michigan | Created state health exchange; expanded Medicaid | 10% | 4% | -60% |

| Florida | Did not create state health exchange (used federal only); did not expand Medicaid | 17% | 11% | -35% |

| North Carolina | Did not create state health exchange (used federal only); did not expand Medicaid | 14% | 9% | -36% |

| Texas | Did not create state health exchange (used federal only); did not expand Medicaid | 20% | 15% | -25% |

SOURCE: Rockefeller Institute of Government analysis of “American Community Survey (ACS),” 1-Year Estimates, Tables S2701 and S2702, United States Census Bureau, access June 7, 2019,

https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs and Michael A. Morrisey et al., Five-State Study of ACA Marketplace Competition: A Summary Report (Washington, DC: Center for Health Policy at Brookings and Albany: Rockefeller Institute of Government, February 2017), https://rockinst.org/issue-area/five-state-study-aca-marketplace-competition/.

As Table 2 illustrates, Texas had the highest uninsured rate in the nation in 2010. However, even though the rate of uninsured dropped in the state by 25 percent after the enactment of the ACA, Texas’ uninsured rate is still the highest nationally today. That Texas, “…has been actively opposed to the ACA. It did not expand Medicaid, it has a federally facilitated exchange, and its department of insurance plays no role with respect to the functioning of the law,” surely had an impact. In contrast to Texas, Massachusetts had the lowest rate of uninsured in the nation in 2010 — only 4 percent — and had the lowest rate of uninsured in 2017 — 2 percent. Massachusetts is credited with having the lowest pre-ACA uninsured rate largely because the state implemented a system like the ACA — known as “RomneyCare” after Governor Mitt Romney — in 2006.

TABLE 2. 2017 Uninsured Rates by Highest to Lowest Uninsured

| State | 2010 | 2017 | Change |

| Texas | 20% | 15% | -25% |

| Oklahoma | 16% | 12% | -25% |

| Alaska | 17% | 11% | -35% |

| Florida | 17% | 11% | -35% |

| Georgia | 17% | 11% | -35% |

| Nevada | 19% | 10% | -47% |

| Mississippi | 15% | 10% | -33% |

| Wyoming | 12% | 10% | -17% |

| North Carolina | 14% | 9% | -36% |

| South Carolina | 14% | 9% | -36% |

| Idaho | 15% | 8% | -47% |

| Arizona | 14% | 8% | -43% |

| Utah | 13% | 8% | -38% |

| Alabama | 12% | 8% | -33% |

| Tennessee | 12% | 8% | -33% |

| Missouri | 11% | 8% | -27% |

| New Mexico | 16% | 7% | -56% |

| Louisiana | 15% | 7% | -53% |

| Montana | 14% | 7% | -50% |

| Indiana | 12% | 7% | -42% |

| Kansas | 11% | 7% | -36% |

| New Jersey | 11% | 7% | -36% |

| Virginia | 11% | 7% | -36% |

| Nebraska | 10% | 7% | -30% |

| South Dakota | 10% | 7% | -30% |

| California | 16% | 6% | -63% |

| Arkansas | 14% | 6% | -57% |

| Colorado | 14% | 6% | -57% |

| Oregon | 14% | 6% | -57% |

| Illinois | 12% | 6% | -50% |

| Maine | 8% | 6% | -25% |

| North Dakota | 8% | 6% | -25% |

| Washington | 12% | 5% | -58% |

| West Virginia | 12% | 5% | -58% |

| New York | 10% | 5% | -50% |

| Ohio | 10% | 5% | -50% |

| Maryland | 9% | 5% | -44% |

| New Hampshire | 9% | 5% | -44% |

| Connecticut | 8% | 5% | -38% |

| Kentucky | 13% | 4% | -69% |

| Michigan | 10% | 4% | -60% |

| Rhode Island | 10% | 4% | -60% |

| Delaware | 8% | 4% | -50% |

| Minnesota | 8% | 4% | -50% |

| Pennsylvania | 8% | 4% | -50% |

| Wisconsin | 8% | 4% | -50% |

| Iowa | 7% | 4% | -43% |

| Vermont | 7% | 4% | -43% |

| Hawaii | 6% | 3% | -50% |

| Massachusetts | 4% | 2% | -50% |

SOURCE: Rockefeller Institute of Government analysis of “American Community Survey (ACS),” 1-Year Estimates, Tables S2701 and S2702.

Containing Healthcare Costs

Aggressive implementation of the ACA has not just been linked to trends showing a reduction in the overall proportion of those remaining uninsured, but also to trends showing better containment of health insurance costs. Analyzing data from the Kaiser Family Foundation, premium increases of the ACA silver health plan — the second-lowest cost plan — has been the lowest in California and Michigan and highest in Florida, North Carolina, and Texas (see Table 3).

TABLE 3. Average ACA Exchange Premiums

| State | 2014 | 2019 | Change |

| California | $300 | $435 | 45% |

| Michigan | $254 | $383 | 51% |

| Florida | $266 | $477 | 79% |

| Texas | $248 | $444 | 79% |

| North Carolina | $298 | $618 | 107% |

SOURCE: Rockefeller Institute of Government analysis of Kaiser Family Foundation review of second-lowest-cost silver premiums at “Marketplace Average Benchmark Premiums,” Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation State Health Facts, accessed June 7, 2019, https://www.kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/marketplace-average-benchmark-premiums/?currentTimeframe=o&selectedDistributions=2014-2019&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D

In other words, states that wanted the ACA to work have had much better success in providing affordable health insurance to individuals and families.

The State of New York Healthcare

New York has been one of the most aggressive states in taking advantage of the various benefits of the ACA program, from expanding Medicaid to creating a successful health exchange. (For a good summary of what New York has done to implement the ACA, see the Rockefeller Institute of Government’s 2016 report, New York: Individual State Report.) New York State has also taken steps to control consumer health costs. For instance, New York controls proposed health insurance premium requests from insurance companies, and has protected essential health services once required under the ACA but rolled back under the Trump administration.

As a result of New York’s aggressive efforts under the ACA to expand health coverage, the uninsured rate went from nearly 10 percent in 2010 to less than 5 percent in 2017, cutting the percent of uninsured New Yorkers in half. This was accomplished through a mix of private insurance and public insurance (such as expanding Medicaid). Today, more than 95 percent of New Yorkers have some form of health insurance, whether private (employer-based, direct purchase, TRICARE/military health insurance) or public (Medicare, Medicaid, Veterans Affairs health insurance) (see Table 4).

TABLE 4. Where New Yorkers Get Their Healthcare

| Employer-Based | Direct-Purchase | Medicare | Medicaid | TRICARE/ Military | VA | Uninsured | |

| 2010 | 48.2% | 9.9% | 12.3% | 17.7% | 0.7% | 1.2% | 9.9% |

| 2011 | 47.7% | 9.5% | 12.6% | 18.7% | 0.7% | 1.2% | 9.6% |

| 2012 | 47.9% | 9.3% | 13.0% | 18.8% | 0.7% | 1.2% | 9.1% |

| 2013 | 47.5% | 9.1% | 13.3% | 19.2% | 0.7% | 1.2% | 9.0% |

| 2014 | 47.1% | 9.7% | 13.5% | 20.5% | 0.7% | 1.2% | 7.3% |

| 2015 | 46.7% | 10.2% | 13.7% | 21.6% | 0.8% | 1.1% | 5.9% |

| 2016 | 46.4% | 10.8% | 14.0% | 21.9% | 0.8% | 1.2% | 5.0% |

| 2017 | 46.4% | 10.9% | 14.3% | 21.8% | 0.7% | 1.1% | 4.7% |

SOURCE: Rockefeller Institute of Government analysis of “American Community Survey (ACS),” 1-Year Estimates, Tables S2701 and S2702, S2703, S2704, B27004, B27005, B27006, B27007, B27008, B27009, United States Census Bureau, accessed June 7, 2019, https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs.

Where is Healthcare Reform Heading?

Even with the healthcare reform occurring under the ACA, there is a push to do more to expand healthcare further to make insurance more accessible and affordable. But the question is, what?

Katherine Hempstead, senior policy adviser at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, said at a recent Rockefeller Institute forum:

Right now, we’re experiencing a period in healthcare and health reform where there’s a lot of creativity but also a lot of dissatisfaction. We are seeing expanded calls for increased coverage, increased access, and increased affordability. And some of those calls are for things that would really disrupt our current paradigm and create a sort of different system altogether.

While under Republican control, the U.S. Congress spent considerable effort trying to repeal the ACA through lawsuits and legislative action. After failing to repeal the law outright, Congress — at the urging and with the support of President Trump — repealed the ACA’s individual shared responsibility provision, better known as the individual mandate. The individual mandate requires individuals or families to purchase a basic amount of health insurance coverage or pay a penalty in order to help keep the cost of the program down for individuals and families. The Trump administration also ended cost-sharing reduction payments (CSRs) which, with the end of the individual mandate, is expected to drive up health insurance premiums. Rockefeller Institute Fellow Jim DeWan has written this extensively on this.

Some proposals to replace the ACA from congressional Republicans broadly discuss universal access, but have received criticism because they would likely only offer an illusion of access as costs of available insurance could become prohibitive for many families.

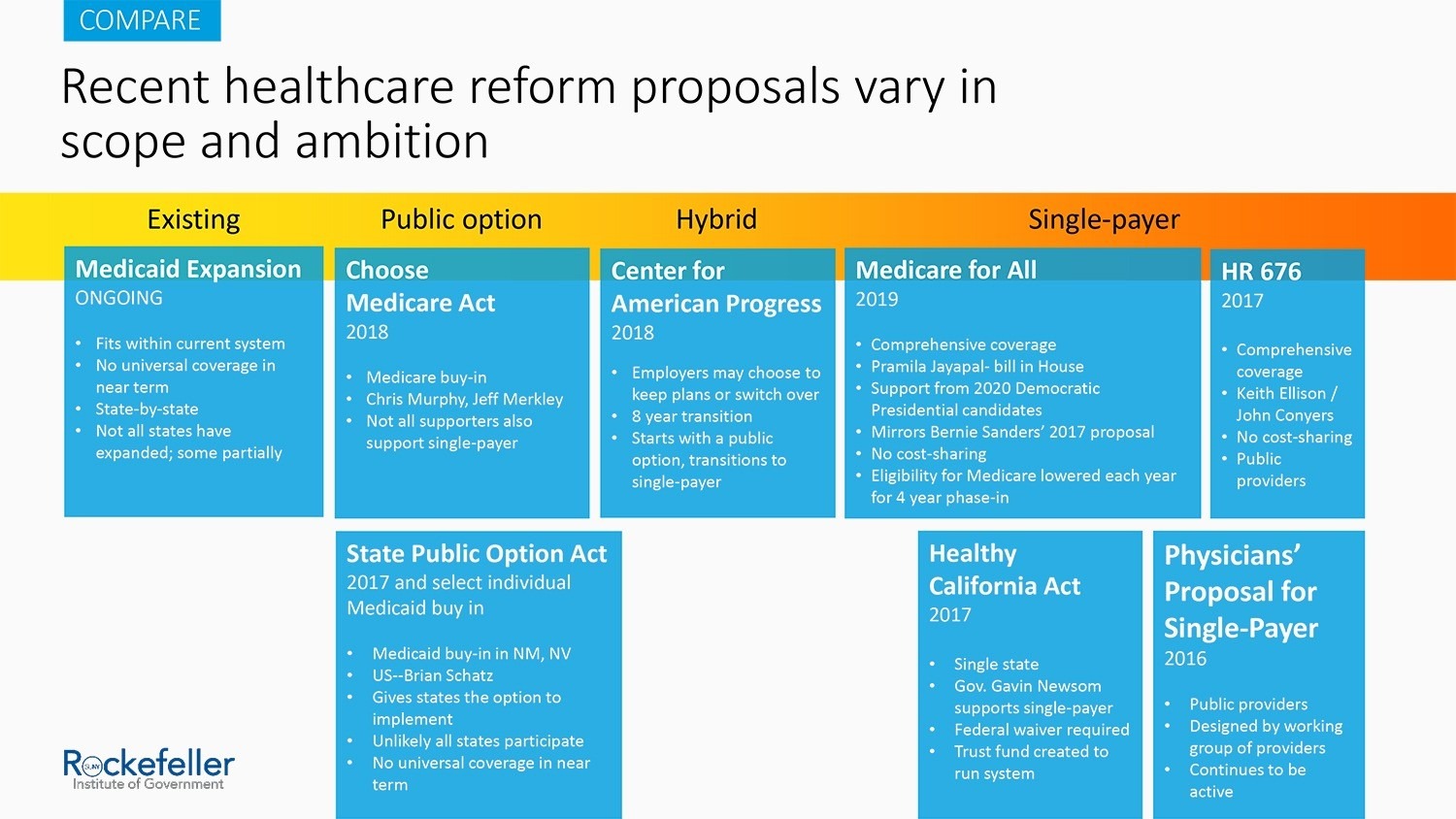

On the other side of the aisle, many Democratic officials and progressive groups have proposed overhauling the healthcare system by creating additional Medicaid buy-in programs or a single-payer system. The Rockefeller Institute’s series on healthcare reform has addressed many of these proposals, including Medicaid for More and single-payer.

Slide from a presentation by authors John Kaelin and Katherine Hempstead at the “Medicaid for More?” forum at the Rockefeller Institute of Government on February 25, 2018, https://rockinst.org/blog/video-medicaid-for-more-forum-at-the-rockefeller-institute/.

Slide from a presentation by authors John Kaelin and Katherine Hempstead at the “Medicaid for More?” forum at the Rockefeller Institute of Government on February 25, 2018, https://rockinst.org/blog/video-medicaid-for-more-forum-at-the-rockefeller-institute/.

In Albany, debates are ongoing about where to go next with healthcare reform. Recent discussion has centered on adopting a more disruptive system, such as single-payer. Given the broad coverage that exists in the wake of aggressive implementation of the ACA and the expansion of services and protections implemented in New York over the past few years, what exactly would be gained from such a dramatic shift? What are the actual costs and potential unintended consequences of moving toward such a system? Would the costs and risks associated with such an experiment be worth jeopardizing the advanced position New York State has already placed itself in?

A diverse cross-section of experts presented on precisely these questions at a February 28, 2019, panel at the Rockefeller Institute of Government. These experts testified that unintended consequences of expanding or overhauling the current system must be thought through thoroughly, including a diminished level of care provided to New Yorkers currently relying on Medicaid, our state’s most vulnerable population, under an overhauled system such as some being proposed currently.

As Lara Kassel of Medicaid Matters said:

Obviously, given the ramifications of ending a system we have now to create more affordability and more coverage for more people, etc. With that said, from the Medicaid consumer perspective, I think it’s really critically important to remember in this conversation that Medicaid, particularly in New York, there are distinct intents behind the Medicaid program. It’s intended to serve low-income people and serves a tremendous purpose for people in particular with long-term and complex needs. With that as a starting place, from my perspective, I think it’s really critically important that we remember that in this conversation. The Medicaid program, again, really ought to be protected and preserved from that standpoint, given the intent of the program.

Bea Grause, president of the Health Care Association of New York State, at another Rockefeller Institute event, said that New York should look to the experience in Vermont, which shelved a similar system because of cost and implementation problems.

These experts are not saying that bold steps and fundamental changes to the system are in and of themselves bad things. But given the data on the low uninsured rate in New York and better cost containment compared to other states, the question is: what problem are policymakers attempting to solve with the various proposals currently under consideration, and do they adequately solve the problem in the best way? Good policymaking should be wary of becoming solutions in search of problems instead of the other way around.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jim Malatras is president of the Rockefeller Institute of Government

Alexander Morse is a research support specialist at the Rockefeller Institute of Government

Nicholas Simons is a project coordinator at the Rockefeller Institute of Government