Mass public shootings, like the May 14, 2022, tragedy in Buffalo, NY, and the attack in Uvalde, TX, just 10 days later, are typically accompanied by a flurry of questions from the public and policymakers. Why did this shooting happen? What drove this person to choose such violence? And why did it occur at this specific location?

Focusing solely on the why, however, often leads to failed attempts at profiling mass shooters or an overprediction of who may commit similar acts. It also fails to take into account that, while motives across these events vary, how individuals move from grievance to violence shares distinct and actionable similarities. Put another way, identifying and examining the typical stages of mass shooting events presents policymakers with a broader array of policy options for prevention than simply focusing on a shooter’s motives.

Research on Mass Shootings from the Regional Gun Violence Research Consortium

- Can Mass Shootings be Stopped? To Address the Problem, We Must Better Understand the Phenomenon. This policy brief examines trends in mass shootings and details broader concerns for policymakers and practitioners.

- Mass Shooting Factsheet. This resource shares data from more than 55 years of mass shootings on demographics of perpetrators, weapons selection, and target selection, among others.

- Policy Solutions to Address Mass Shootings. By evaluating the effect of state gun laws on mass public shootings, this policy brief finds gun permits and bans on large capacity magazines may reduce mass public shooting rates and mass public shooting victimization, respectively.

- Assault Weapons, Mass Shootings, and Options for Lawmakers. Presenting data that show the that mass shootings carried out with assault-style weapons are far more deadly than those involving a handgun, this policy brief looks at what solutions may be available to reduce deaths and injuries from these weapons.

The Path to Intended Violence

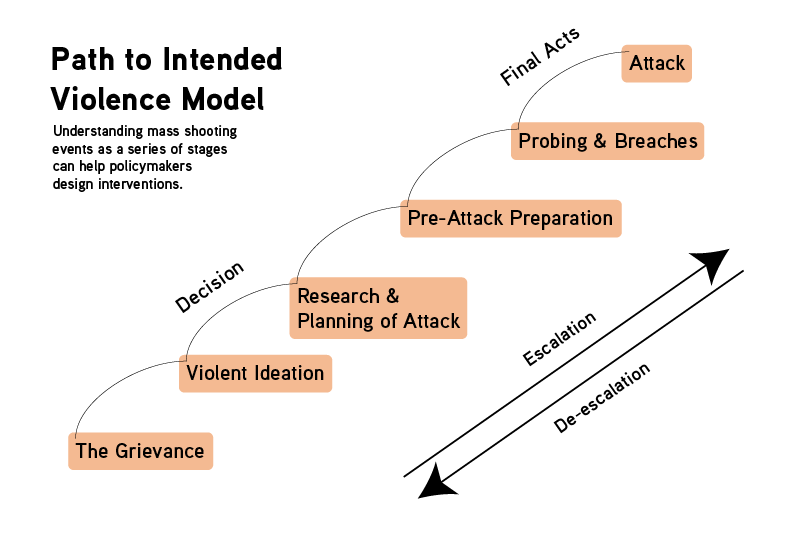

A guiding framework for understanding these stages is the Path to Intended Violence model, which outlines the progressive phases individuals may pass through ahead of committing acts of violence. The path begins with a grievance harbored by the perpetrator, which may either be real (e.g., loss of a job or relationship) or perceived (e.g., driven by paranoid or delusional thinking). Unable to move past the grievance, the individual becomes fixated on it and engages in ideation wherein they fantasize about responding to the grievance through violent means.

NOTE: Adapted from Calhoun and Weston (2003) and White and Meloy (2017).

At some point, the individual makes the decision that they are going to take their idea from fantasy to reality, and they begin planning their attack. This often involves researching previous attacks and their perpetrators and deciding on where they will carry out their plan and surveilling it (depending on their level of familiarity with the location), among other logistical considerations.

Individuals engage in preparation activities, such as acquiring their weapon(s), ammunition, and other elements (e.g., body armor). It is at this point that they may also craft manifestos or other legacy tokens or give away personal belongings. Since these behaviors are often noticeable, which could lead to the plan being thwarted, individuals may become more isolated during this stage of the process.

Once the plan is set and the individual has acquired the means to carry it out, they may engage in probing behaviors, during which they test for security and other potential barriers to carrying out their plan at the intended location or conduct a dry run. At this point, the attack is imminent. Though some individuals ultimately may decide not to go through with their plan, others will continue forward and carry out their attack if the opportunity to do so is not removed.

While the stages on the Path to Intended Violence are progressive, how individuals proceed through them may not be linear. Individuals may spend more time in certain stages compared to others or they may skip stages entirely. The rate at which they travel along the path may also vary, with some individuals spending weeks planning and preparing and others taking months or even years. Still, by understanding how these behaviors can escalate, it provides opportunities for the identification, assessment, and management of the threat to deescalate the individual and prevent the attack from occurring.

Leakage

Another important aspect of this process is the act of leakage, which occurs when individuals are so consumed with thoughts of their fantasies and plans that they cannot keep it to themselves. Leakage can occur through different channels, such as directly telling their plan or making threats to other individuals or sharing through social media. Individuals may also chronicle their plans and the steps taken in journals, letters, or blogs.

A 2019 report from the US Secret Service, for example, found that more than 75 percent of school shooters communicated their intentions ahead of their attack. This pattern has also been found among perpetrators of mass shootings beyond schools. Oftentimes, at least one person—though multiple people in more than half of cases—knows about the threat but fails to report it. And research on averted mass shootings shows that the main reason these plots were thwarted was because someone with information came forward.

…more than 75 percent of school shooters communicated their intentions ahead of their attack.

Leakage is an overt warning sign that may occur at any stage on the path. As such, it is important that individuals who become aware of these statements report them to the authorities for further investigation and threat assessment immediately. Oftentimes, this does not happen due to the bystander effect—the phenomenon where individuals feel less personal responsibility to act when others are also aware of a threat or crisis—or because individuals fear repercussions for reporting.

Research Informing Policy

Efforts to prevent mass shootings should focus on disrupting the perpetrator’s journey along the Path to Intended Violence. This can be accomplished in three key ways.

First, to combat the bystander effect, efforts should be made to educate the public about what leakage looks like, the necessity to report it, and how to do so. Following the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, the US Department of Homeland Security launched their “If You See Something, Say Something” campaign designed to teach the public to recognize and report suspicious activity. Modeling a similar campaign around leakage and warning behaviors may increase both identification and reporting of mass shooting threats.

During the last school year, the Safe2Tell reporting platform received more than 11,300 tips, with 95 percent identified as actionable.

Second, mechanisms for reporting, such as anonymous tip lines, should be employed to provide an outlet to gather and manage identified threats. Several years after the 1999 shooting at Columbine High School in Colorado, the Safe2Tell program emerged as a method for students, parents, and community members to report information about safety issues and have it referred immediately to the appropriate channel, like law enforcement or mental health agencies. Anonymous tips can be submitted through different modalities (e.g., phone calls, mobile, and computer apps) for a range of concerns, including violence against others. During the 2020-21 school year, the platform received more than 11,300 tips, with 95 percent identified as actionable.

Third, community-based threat assessment teams, which include representatives from law enforcement, courts, mental health professionals, schools, and other vested stakeholders, should be used to assess the credibility of the threat and develop and deploy a corresponding management plan. Having various stakeholders collaborating in this capacity also increases the likelihood of information sharing and reduces “information silos” that have historically made preventing mass shootings difficult.

A Call for Researchers and Policymakers

While understanding why mass shootings happen is important, identifying how to stop them requires a focus on how individuals escalate from grievance to the attack. Looking to previous mass shootings and their commonalities—the perpetrators’ preattack behaviors—provides an important starting point.

Researchers have been studying mass shootings and have a strong understanding of the Path to Intended Violence and how perpetrators of these tragedies move through its associated steps. Policymakers and researchers should work together to identify interventions that can be the most impactful in preventing future tragedies. Leveraging existing resources developed out of other mass casualty events, including terrorism, can also help guide these efforts.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jaclyn Schildkraut is the interim executive director at the Regional Gun Violence Research Consortium at the Rockefeller Institute of Government and an associate professor of criminal justice at the State University of New York (SUNY) at Oswego.