In July 2019, New York established a commission to explore how rapidly evolving artificial intelligence (AI) and automation technologies can be used to benefit New Yorkers and the state’s economy. This is a question the Rockefeller Institute has addressed in its blog series AI:NY. The first installment found that 53 percent of New York could be facing automation in the near future. A panel of experts saw big opportunities for AI in the fields of healthcare, finance, and education, and called for an educational system that would prepare New Yorkers for the high-skills workforce of the future. The recent AI predictions are very similar to those made at the beginning of the digital revolution in the 1980s and 1990s. As policymakers consider how to respond to new technologies, it can be useful to see how accurate previous predictions have been in forecasting the impacts of other game-changing technologies.

In this post, I explore the accuracy of the predictions made at the initial roll-out of Information and Communications Technologies (ICTs). ICTs were the suite of technologies that enabled the “information age” or “digital revolution,” including the adoption of personal computers, the internet, the eventual creation of smart phones, and obsequious connectivity. At the dawn of the digital revolution, economists questioned whether or not we were entering the next industrial revolution. They forecasted dramatic leaps in our personal productivity, automation of mundane tasks, changes in the workforce, globalization, and self-employment. These are many of the same predictions being made today as artificial intelligence lays on the horizon.

At the dawn of the Digital Revolution, economists and technologists forecasted a fundamental shift in the American economy. US employment and output would move away from the production of goods and focus on services. At the time, this was not a surprising prediction. New production technologies made labor a relatively less important input in the production process. American manufacturing was being done in high-tech, capital-intensive factories producing high-value products such as electronics and automobiles. The more labor-intensive manufacturing of nondurable goods such as textiles had already started moving overseas.

At the time, economists likened the shift to the industrial revolution when employment transitioned away from the agricultural sector into manufacturing. Emerging ICTs were shifting information storage and processing from large mainframes and networks owned by large companies, universities, and governments to personal computers in workplaces, homes, and schools. It was a time of excitement and uncertainty with a wide range of predictions regarding the future of work. Some were optimistic about the possibilities the new technologies would bring and others feared a collapse of the labor market.

If the new information technology is properly employed, it can enable organizations to attain … the elimination of redundant work and unnecessary tasks such as retyping and laborious manual filing and retrieval; better utilization of human resources for tasks that require judgement, initiative and rapid communications; faster, better decision making that takes into account multiple, complex factors and full exploitation of the virtual office through the expansion of the workplace in space and time. (1982) [1]

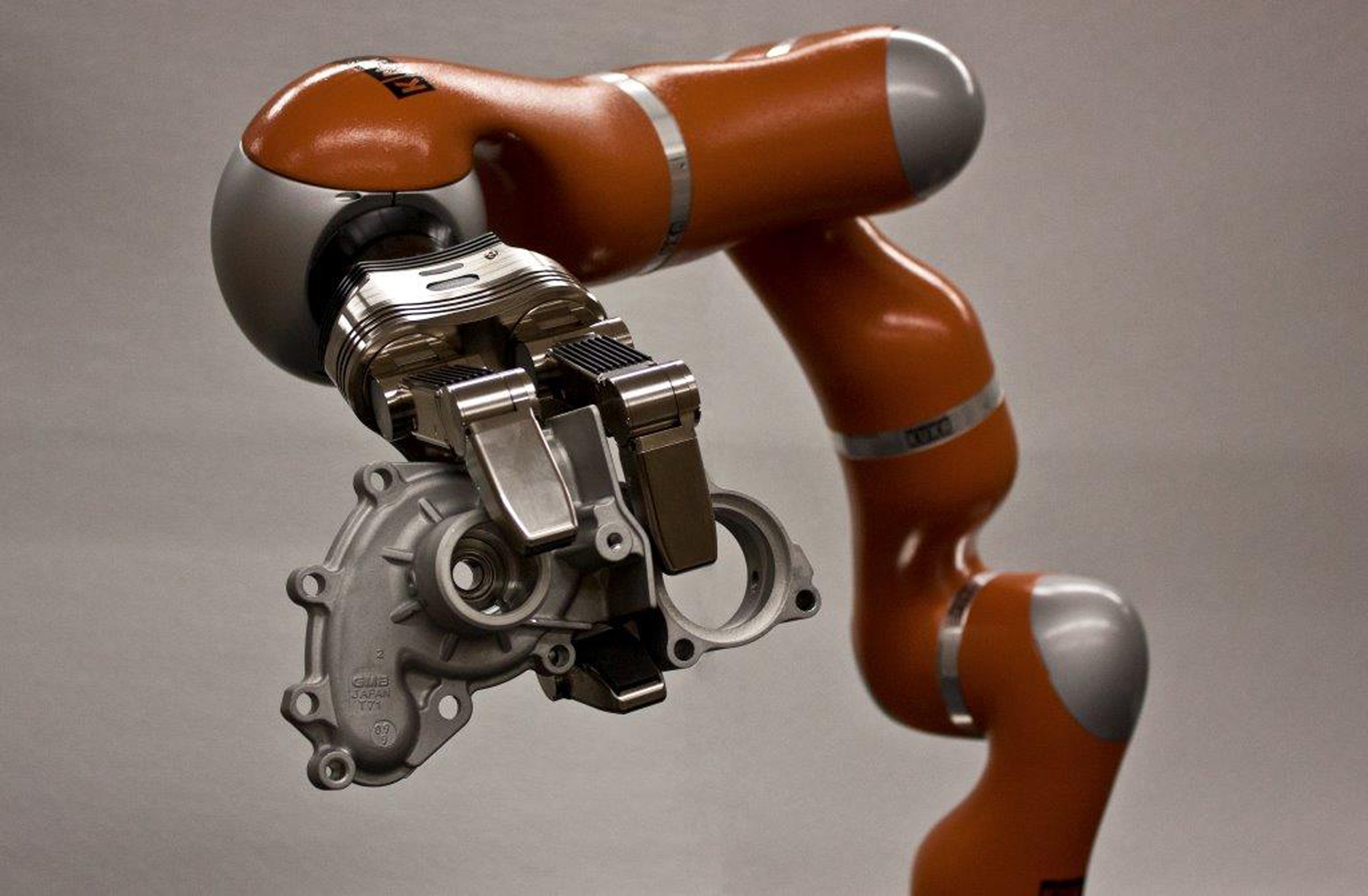

Silicon secretaries that can take dictation and edit letters, reservation clerks that understand speech in any language, or robots that can load a truck or pick strawberries are easily within the reach of technologies being developed now. By the year 2000 such machines will be coming into wide use. Even much more sophisticated tasks such as diagnosing illnesses or writing computer programs may be partly automated by the turn of the century. (1987)

Worldwide, more than a billion jobs will have to be created over the next ten years to provide an income for all the new job entrants in both developing and developed nations. With new information and telecommunication technologies, robotics, and automation fast eliminating jobs in every industry and sector, the likelihood of finding enough work for the hundreds of millions of new job entrants appears slim. (1995) [2]

It was well recognized by both the optimists and pessimists that manufacturing was on the decline and that, moving forward, US output and employment would be concentrated in the service-based sectors. The shift into services came with anxiety. In 1980, the largest service sector was Retail Trade, accounting for 21 percent of service-related labor, which was considered relatively low-wage, part-time employment. People were concerned that well-paid manufacturing jobs would be lost and replaced with lower-quality service positions.

The coming decades proved the more optimistic economists generally correct. (The robots that pick produce in fields and roll around offices delivering mail have yet to materialize.) There was a dramatic shift in US employment from goods to services. Since 1980, the number of people employed in private service-producing jobs has more than doubled and the number of goods-producing jobs has fallen by 15 percent. At the beginning of the 1980s, goods-producing jobs were a third of the workforce; by 2018, their share fell to 16 percent.

FIGURE 1. U.S. Private Employment, in Thousands, 1980-2018

SOURCE: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Current Employment Statistics (National)

Table 1 explores the make-up of the service industry at three points: 1980 (introduction of the PC), 1995 (introduction of the internet), and 2018. Since 1980, employment in the US has grown at a rate of 1.4 percent a year. This has been driven by growth in service-based employment (2.0 percent annually) that has offset losses in goods-producing employment (-0.4 percent annually). The jobs created have been dominated by three service sectors: education and healthcare, professional and business services, and leisure and hospitality. These industries represent 39.6 million of the 56.0 million new services jobs created since the digital revolution. In 1980, they accounted for 42 percent of service employment and last year they made up 57 percent.

TABLE 1. Employment Trends in Services, 1980-2018

| Share of Service Employment | Average Annual Growth, 1980-2018 | Average Pay, 2018 | |||

| 1980 | 1995 | 2018 | |||

| Education and Healthcare | 14% | 18% | 22% | 3.23% | $50,442 |

| Professional and Business Services | 15% | 17% | 20% | 2.72% | $75,156 |

| Leisure and Hospitality | 13% | 14% | 15% | 2.37% | $24,074 |

| Other Services | 6% | 6% | 6% | 2.00% | $38,474 |

| Transportation | 6% | 5% | 5% | 1.60% | $53,215 |

| Financial Activities | 10% | 9% | 8% | 1.41% | $95,574 |

| Retail Trade | 21% | 19% | 15% | 1.15% | $32,357 |

| Wholesale Trade | 9% | 7% | 6% | 0.68% | $77,879 |

| Information | 5% | 4% | 3% | 0.48% | $113,795 |

| Utilities | 1% | 1% | 1% | -0.42% | $109,947 |

SOURCE: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Current Employment Statistics (National)

In the 1980s, growth in the education and healthcare sectors were both anticipated. The new technologies would require additional educational credentials, and education was a sector in which the US had global dominance. Forecasters accurately predicted the expansion. With the aging population requiring more care, healthcare growth was also expected.

The professional and business services industries include professional, scientific, and technical services; management of companies and enterprises; and administrative and support services. This well-paid sector represents many of the new jobs created by the digital revolution related to computer systems and software design. In the 1980s, it would have been hard to imagine data center employment, app developers, and digital marketing consultants. This sector also includes new businesses that were enabled as a result of the digital economy. Global connectivity has enabled new economies of scale in the management of firms. Traditionally functions such as human resources and engineering and design were kept in-house at a firm creating significant administrative costs. Digital technologies made it easier for companies to transfer these functions outside of the enterprise by hiring expertise on an as needed basis. The result was the creation of thousands of new firms in the management of companies and enterprise sector.

Leisure and hospitality has expanded as the digital revolution created higher wages and more wealth globally. The result is greater demand for entertainment and travel, driving up employment in this sector. Economic forecasters of the 1980s knew that this sector was going to change thanks to the digital revolution, but were wary to predict exactly what new forms of amusement would emerge.

What does this mean for AI?

Looking back, we see that, in fact, the Luddites were right; the digital revolution brought job losses in manufacturing. Since the 1980s, the US has lost over 3.5 million manufacturing jobs. But what these forecasters failed to take into account were the gains generated to offset losses. For every manufacturing job lost since 1980, 15.8 new jobs in service industries were created.

It takes decades of hindsight to identify the technologies that will change the structure of our economy and society. Every few years, economists ask if nanotechnology, 3-D printing, the internet of things, or (enter your favorite trendy tech here) is the innovation that will dramatically change the way our economy and labor force functions.

We are presently at the moment where we can ask if AI is going to bring about dramatic structural changes. Many of the changes predicted at the dawn of the digital age are the same ones promised by AI’s proponents: programs that diagnose illnesses, immediate translation of spoken language, and automation of mundane office tasks. The concerns regarding job loss due to automation are the same that are repeated when new technologies are introduced. The most important lesson to be learned by previous forecasters is that it is very easy to see the jobs that will be replaced by technology, but nearly impossible to imagine the opportunities that will be created.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Laura Schultz is director of fiscal analysis and senior economist at the Rockefeller Institute of Government

[1] Vincent E. Giuliano, “The Mechanization of Office Work,” Scientific American 247, 3 (1982): 149-64.

[2] Jeremy Rifkin, The End of Work: The Decline of the Global Labor Force and the Dawn of the Post-Market Era (New York: Warner Books, 1996).

AI:NY

Is New York Prepare to Lead AI?

Does New York have the workforce required to lead the development of this emerging sector? What can New York do to prepare itself to take advantage of the growth and opportunity created by AI?

The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on the Labor Force in New York State

Fifty-three percent of jobs in New York could be automated with technology available today or anticipated in the near future, while 56 percent of workers across the US face threats from automation.

AI Policy Forum: The Big Takeaways

SUNY’s Office of Research and Economic Development and the Rockefeller Institute of Government gathered experts from industry, government, and academia to discuss New York’s role in the development and adoption of artificial intelligence (AI). We offer six takeaways.

How Drones are Changing the Role of the Utility Worker

We explore how new technologies are changing the nature of jobs in the electric utility sector and how the sector is adapting to reflect those changes with a case study from the New York Power Authority.