In the spring of 2022, the Center for Law and Policy Solutions student interns conducted an in-depth study of green infrastructure. Inspired by historic levels of federal funding for infrastructure, they wanted to know how local communities could use these funds to address the environmental health challenges related to both legacy infrastructure and continuing climate change.

Over the course of the semester, they explored how more volatile weather, increased precipitation, and rising sea levels were further impacting local water systems already in need of repair or replacement; they spoke with municipal leaders in the Northeast and Midwest to learn more about the investments being made in communities to try to address these challenges; and they presented their initial findings in a webinar. Their work has been further developed into a series of blogs that discusses the intersecting challenges of climate change and aging infrastructure, introduces the role green infrastructure can play, and highlights how two municipalities have integrated green infrastructure into their water systems.

Our previous two blog posts considered the challenges of aging wastewater infrastructure and climate change in the United States and introduced the types of green infrastructure that can be used to address those challenges. In this blog, we will look at examples from two cities—Toledo, Ohio and Albany, New York. In recent years, both cities and their aging sewer systems have been forced to contend with stormwater and wastewater challenges. In response, these cities have implemented a series of green infrastructure projects as part of their long-term planning.

Implementing Green Infrastructure in Toledo, Ohio

The city of Toledo has a population of nearly 300,000 people and covers roughly 80 square miles, lying at a low and relatively flat elevation of 614 feet. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) stated that with the onset of climate change and the city’s location on Lake Erie and the Maumee River, Toledo is particularly susceptible to flooding. The region around and including the city was once known as the Great Black Swamp—a significant wetland accustomed to heavy rain. Prior to development, the swamp helped absorb excess precipitation, but the city’s buildings and pavements are more impervious. According to NOAA, 9,370 acres or 92 percent of the surrounding watershed is now covered in paved materials. In addition, Toledo’s wastewater infrastructure dates back to the 1860s, with one report estimating “approximately 20 percent of Toledo’s existing sewer system is a combined sewer and stormwater system.” These aging systems in Toledo continue to be challenged by the ever-increasing rainfall and extreme storm events. Between 1951 and 2017, the city experienced a 19.4 percent increase in rainfall.

To address overflow, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) found the city had a “long-standing practice of discharging raw sewage into Swan Creek and the Maumee and Ottawa Rivers.” In 2002, the EPA and the City of Toledo reached a settlement under the Clean Water Act to improve its wastewater treatment and transportation systems. At that time, the agency estimated that the improvements would eliminate “nearly 800 million gallons of raw sewage overflows annually.”

Under that agreement, from 2005 to 2009, the City developed the Toledo Waterways Initiative (TWI) Long-Term Control Plan (LTCP) for combined sewer overflow (CSO) abatement. The Control Plan “recommended implementing sewer separation, storage basins or tunnels, green infrastructure, disinfection facilities, etc. as appropriate, for each CSO.”1 By 2020, the TWI had implemented over 45 projects at a cost of approximately $529.7 million. Chief of Water Resources Patekka Pope Bannister for the City of Toledo stated in 2014 that “locally there is a perception that people see green infrastructure projects as things that happen on the East Coast or the West Coast, and we can show them that we have examples here.” NOAA and Toledo conducted research, funded by the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative administered under the EPA, to assess the cost and benefits of implementing green infrastructure to address flooding and overflows. Patekka and others from the City and NOAA gathered data on local flooding, economic impacts, and estimated the potential of particular green infrastructure projects to divert and absorb excess precipitation.

That research outlined the structural damages estimates for a 100-year storm event in Toledo’s Silver Creek watershed “for current and future flooding scenarios, both with and without green infrastructure.” As reflected in the table below, cost estimates with green infrastructure were far below those without it, reducing current flooding impacts from roughly $740,000 to $450,000 and reduce future impacts from nearly $1 million to $528,000. The implementation of green infrastructure, therefore, had the potential to lower the cost of flooding damages by $284,600 to $453,300 per storm.

In addition to the direct impacts monetized in the report, the research team noted the importance of considering the indirect benefits realized by residents including improved water quality and increased property values. Including these indirect benefits would shorten the time period required to realize the return on investment.

Structural Damage Assessment for the Toledo Case Study

| Silver Creek Scenario (all 100-year storm event data) |

Number of Buildings Damaged | Maximum Single Building Damage ($) | Total Damage for all Buildings ($) |

| Current flooding without a green infrastructure strategy | 253 | $52,000 | $738,300 |

| Current flooding with a green infrastructure strategy | 159 | $53,200 | $453,700 |

| Future flooding without a green infrastructure strategy | 293 | $67,300 | $980,800 |

| Future flooding with a green infrastructure strategy | 179 | $53,500 | $527,500 |

Maywood Avenue Stormwater Volume Reduction Project

In 2011, the City of Toledo launched The Maywood Avenue Stormwater Volume Reduction Project. Maywood Avenue is a residential neighborhood and the project was viewed as a potential test for a larger-scale green infrastructure implementation throughout the city. The project was funded by the Ohio EPA, US Department of Agriculture, and Lucas County. Key partners included the local organization Toledo GROWS, a subdivision of the Toledo Botanical Gardens, and a national organization called Biohabitats. The green infrastructure components of the project cost $278,000, with total project costs of $500,000.

The project reconstructed the neighborhood streetscape, making sidewalks permeable, retrofitting right-of-ways and lawns to accommodate bioswales, implementing rain gardens and rain barrels on private property, etc. The bioswales spanned the length of both sides of Maywood Avenue and residents were given the choice of using different plants (buffalo grass, native flowers, or street plants). In collaboration with the City of Toledo, the homeowners agreed to care for the bioswales.

A Google Maps screenshot of the bioswales on Maywood Avenue in Toledo, Ohio.

The project reduced the average stormwater runoff on Maywood Avenue by 64 percent. Consequently, this partnership between Toledo and its residents highlights the importance of partnering with and providing resources and education for residents when implementing green infrastructure.

Cullen Park

The City then pursued funding for and the implementation of a range of projects, receiving $500,000 from the EPA’s Great Lakes Shorelines Cities Green Infrastructure Grants for “a street retrofit in the Silver Creek watershed and a series of green infrastructure projects within Cullen Park” adjacent to Lake Erie and the Maumee River. The Cullen Park portion of the project, which cost $300,000, featured the creation of new vernal pools or ponds with vegetation to divert excess precipitation. These ponds retain up to 650,000 gallons of water and help slowly drain that water into waterways, reducing local flooding.

Illustrative images of green infrastructure design from Cullen Park Best Management Practices, Mannik Smith Group.

Examples of Green Infrastructure from Albany, New York

The city of Albany lies along the Hudson River in New York State’s Capital Region. Albany and five of its surrounding municipalities (Troy, Cohoes, Watervliet, Green Island, and Rensselaer) rely on combined sewer systems and send a combined 1.3 billion gallons of untreated sewage and stormwater into the Hudson River. The Albany CSO Pool Communities Corporation (or, the Albany Pool) is a partnership of the municipalities and, similar to the TWI, is responsible for outlining and implementing the area’s Long-Term Control Plan required by the state’s Department of Environmental Conservation to improve local water quality. There are 92 Combined Sewer Overflow points in the Albany Pool region of the Hudson River. Pollutants that are of concern in the Capital Region from stormwater runoff and wastewater overflows, as in other areas, include bacteria, viruses, chlorine, trash, sediment, chemicals, and oil all of which are detrimental to the region’s waterways and human and ecological health.

To address the overflows, the City of Albany has already implemented a handful of projects to reduce stormwater runoff and overflows, including the Quail Street Green Infrastructure Project and the Hansen Alley and Ryckman Alley Overflow Abatement and Flood Mitigation Project. Both projects were implemented after an intense storm in 2014 that dumped three inches of rain on the city “resulted in several feet of water and combined sewer flooding residents’ homes.” These projects were designed to reduce stormwater flow to the combined sewer system to help reduce the intensity and frequency of CSO events.

Left: An image of flooding near Quail St. and Western Ave. in Albany, NY. Credit: Daniel Van Riper. Right: A worker with a trowel huddles over porous pavement on Quail St. in Albany, NY. Credit: CHA Consulting, Inc.

Quail Street Green Infrastructure Project

Quail Street which runs from Madison Avenue to Central Avenue in Albany has suffered from flooding in the past. In 2015 the Quail Street Green Infrastructure Project sought to mitigate and prevent such flooding from recurring.

The project accomplished this by collecting the first three inches of rainfall in porous pavement and storm sewers and directing runoff into bioretention basins until the flow in the combined sewer system returns to its functional level. This project was largely funded by the Green Innovation Grant Program (GIGP) which contributed $1.8 million. The funding also included $682,000 from The Albany Water Board, $293,000 from the City, and a $300,000 grant designated by the office of state Assemblywoman Patricia Fahy. In addition, the project included collaborative educational components, carried out by higher education institutions located in the same neighborhood—the College of St. Rose and the University of Albany’s Downtown Campus.

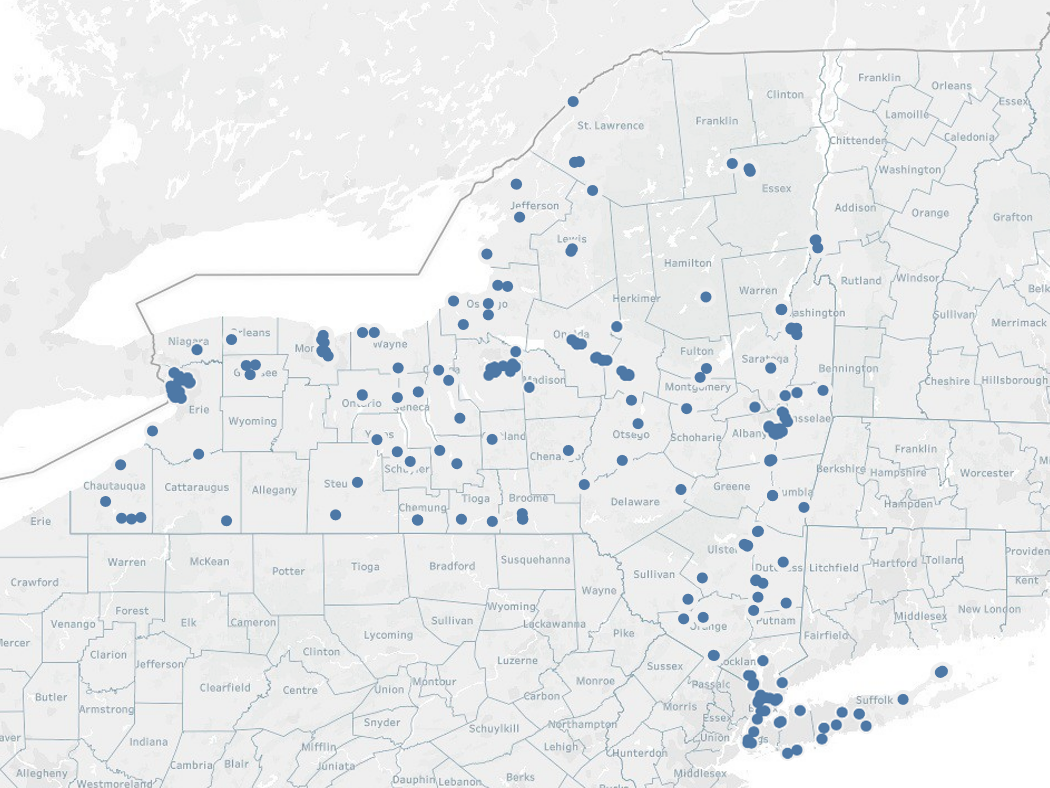

Green innovation grant program project locations throughout New York State, courtesy of Brian Gyory, NYS Environmental Facilities Corporation.

The Green Innovation Grant Program (GIGP) under the New York State Environmental Facilities Corporation provides up to $3 million in funding for local projects related to not only green stormwater infrastructure, but energy efficiency, water efficiency, and environmental innovation. The program has disbursed $143,593,673 to 198 projects across the state since its inception, according to GIGP’s Assistant Project Manager Brian Gyory.

In the end, the project resulted in an annual 0.22 percent reduction in combined sewer overflow for the entire Albany pool. While this may seem small with respect to the broader pool-wide impact, this project has captured 8.867 million gallons annually. In addition to reducing the chance of major flooding, the project is visually pleasing for the neighborhood and helps improve pedestrian and cyclists traffic flow.

Hansen Alley and Ryckman Alley Overflow Abatement and Flood Mitigation Project

The Hansen Alley and Ryckman Alley Overflow Abatement and Flood Mitigation Project is an example of a green infrastructure project that was carried out alongside grey infrastructure improvements—particularly, the separation of stormwater pipes. Hansen Alley is a small passageway in a residential area that serves as an access drive for residents to reach their driveways. This project is located between Hansen Avenue and Woodlawn Avenue, a low-lying region where large amounts of stormwater runoff often collect. In addition, the area abuts a park that is home to the neighborhood Little League. The total drainage area includes 13.7 acres with 7.4 acres or 54 percent of this area being impervious.

As a result of the improvements, stormwater is now collected in separate storm sewer pipes and carried to an underground chamber system that is located beneath the adjacent little league field. The maximum volume of the underground chamber is 776,500 gallons. This allows for the reduction of flooding and runoff that would otherwise collect in combined sewers leading to flooding or overflow. The City has outlined future plans to support the reuse of the collected rainwater, in part for irrigating the baseball field, by implementing a pump station.

Ryckman Alley also serves as an access drive to the driveways of residents’ homes. The project is located in the residential area between Ridgefield Street and Ryckman Avenue, which is also a low-lying region. The total drainage area is 10.5 acres with 2.1 acres or 20 percent of this area being impervious. Next to Ryckman Alley, the project constructed wetlands, including marsh areas and low pools for excess water that can hold 350,000 gallons, with a maximum wetland volume of 640,300 gallons.

The project was funded partially by the New York State Environmental Facilities Corporation (EFC), which includes a $450,000 grant from the Green Innovation Grant Program (GIGP) and a $600,000 Integrated Construction Solutions (ISC) grant. The City of Albany and the Albany Water Board produced simulated results in order to estimate the impacts of these projects. In the performance analysis of the Ryckman Alley project, it was found that after experiencing 1.59 inches of precipitation, there was zero cubic feet of wet weather flow and zero cubic feet of discharge. And, in the performance analysis of the Hansen Alley project, it was found that after a total inflow of 120,000 feet3 of water there was zero feet3 of wet weather flow, meaning there was a 100 percent reduction.

When talking about the impacts of green infrastructure projects like those on Quail Street and Hansen and Ryckman Alley’s, Neil O’Connor, the engineer supervisor for the Albany Water Department, noted that “we don’t necessarily solve flooding. We do the best we can but we can only design a pipe for a certain amount of flow. So we’re trying to mitigate storms that we’re seeing right now. But should climate change continue, who’s to say that 20 years from now there’s not going to be a six inch in one hour storm that the city’s going to be dealing with.” These remarks highlight the crucial role that investments in green infrastructure can play alongside the repair and replacement of grey infrastructure, as communities seek to ensure that they have more resilient systems in the face of aging infrastructure and climate change.

Conclusion

While green infrastructure cannot replace the much-needed improvements municipalities must make to their gray infrastructure, the examples of projects in Toledo and Albany highlight the particular importance of integrating green infrastructure into existing urban infrastructure and new grey infrastructure projects. They further emphasize the value of starting with smaller projects; engaging with community members throughout project formation, implementation, and maintenance phases; establishing partnerships with educational institutions and other stakeholders; and leveraging experience and expertise to right-size the impacts and costs of green infrastructure projects, and measure the actual impacts once the project is implemented.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR(S)

The authors were Center for Law & Policy Solutions (CLPS) research interns for the spring 2022 semester.

[1] That consent decree was amended first in 2011, and is undergoing a second amendment in 2022.