At the international level, it is often thought that Mexico, under the current government, has moved from a militarized and security-based drug policy towards a more humane policy focused on people and their health. However, the signals are not clear on the part of the new administration because, although there are some officials clearly in favor of the regulation of illegal drugs and a health-based perspective, other officials and the president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, persist in a rhetoric of criminalization and stigmatization of people with problematic drug use, which exacerbates the difficulty that these populations experience in accessing health services. This blog describes how the lack of a public harm reduction policy in Mexico has led to the systematic de-funding of this type of intervention, which has, in turn, generated a harm reduction crisis in the north of the country.

Public Financing for Harm Reduction in Mexico

Since 1988, civil organizations in Mexico have carried out harm reduction interventions with the support of international organizations and universities. Through these interventions, people with problematic drug use, who live in contexts of extreme marginality, can gain access to health services. From 2011 to 2018, the National Center for AIDS Prevention and Control (Spanish acronym CENSIDA) financed harm reduction projects that civil organizations implemented mainly on the northern border of Mexico. According to CENSIDA data, these interventions prevented 4,000 new HIV infections between 2013 and 2018.[1]

Despite the success of the interventions financed by CENSIDA, since February 2019, the president canceled by decree all public financing for citizen-led interventions, citing the need to prevent corruption and diversion of public funds. This measure affected the harm reduction programs carried out on the northern border of Mexico, and it particularly affected the smaller and more recently established community-based organizations, which depended mainly on national financing.

Although this unilateral decision by the national executive made many community-based organizations unable to subsist, the decrease of public funds for harm reduction activities is a trend observed since 2013 — the year in which the Global Fund Project ended (see below) — and is the consequence of the absence of a public policy on the subject and the emphasis on abstinence as the only alternative to drug use.

The Fallacy of Harm Reduction in Mexico

Although the Official Mexican Rule for the prevention, treatment, and control of addictions (NOM-028) establishes that harm reduction is a strategy focused on prevention and treatment activities, this is nothing more than an abstract formulation. There are no binding mechanisms that compel the entities of the republic to carry out activities of this kind, nor is there currently a budget to implement plans, programs, and projects aimed at promoting the health of people who, for various circumstances, use drugs and cannot or do not want to stop using them. Consequently, the articulation between prevention, harm reduction, and treatment ends up being only a formulation of NOM-028 which, not being translated into a strategy, leads to abstinence being the exclusive goal of national policy towards drug use.

The only public institution that offered financing for harm reduction projects in Mexico was, as mentioned, CENSIDA. However, the centrality of HIV in harm reduction strategies and programs is still problematic. First, because the focus of HIV restricts the financing of strategies, programs, and projects aimed at users of noninjected drugs. Second, because it limits the perspective of harm reduction to syringe-exchange activities and access to diagnostic tests for HIV and Hepatitis C, without the state guaranteeing access to treatment under the assumption that “addicts” are noncompliant.

Despite CENSIDA’s interest in financing harm reduction strategies, the absence of a public policy on the matter has resulted in the stagnation and drastic fall of some indicators on the subject, including: number of distributed syringes, number of institutions that offer substitute treatment for opioids, and number of organizations that implement harm reduction actions (see Censida Reports from 2009 to 2018).

The Fall in Harm Reduction Indicators

Although the distribution of syringes has been a priority in the harm reduction activities financed by CENSIDA, Mexico has never approached the 200 syringes per person recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO), and things have progressively gotten worse. Data from CENSIDA indicate that, between 2012 and 2013, the highest number of syringe distribution was achieved (19.7). This was achieved within the context of the implementation of the Global Fund Project to strengthen the national response to HIV/AIDS. In 2014, there was a 30 percent reduction in the volume of distribution of syringes. As Figure 1 shows, only three syringes per person were distributed in 2017 — a trend that clearly does not favor HIV prevention.

FIGURE 1. Number of Syringes Distributed to People Who Inject Drugs, 2008-17 [2]

SOURCE: Author’s calculations based on data from CENSIDA, 2009-18.

The number of institutions that offer opioid replacement therapy (e.g., methadone) has also decreased significantly. While in 2013 CENSIDA recorded the existence of 21 institutions throughout the country, in 2017 the Federal Commission for Protection Against Sanitary Risks (Spanish acronym COFEPRIS) only recorded 10. To this we must also add the closures of institutions due to medicine shortages that are reported at least once a year, but for which there are no official records regarding the number of days in which these institutions were closed or the consequences that these closures had in the treatment of the users of these services.

FIGURE 2. Number of Institutions That Deliver Methadone Treatment in Mexico, 2013, 2014, and 2017 [3]

SOURCE: Author’s calculations based on data from CENSIDA.

The number of community-based organizations that carry out harm-reduction interventions on the northern border has also fallen dramatically in recent years. According to CENSIDA reports, while in 2014 38 organizations were registered, and in 2017 only eight continued conducting harm reduction. It is very likely that by the end of 2019 this number will be even lower given the lack of funding faced by some of the organizations.

FIGURE 3. Number of Community-Based Organizations That Offer Syringe Exchange in Northern Mexico, 2014, 2016, and 2017 [4]

SOURCE: Author’s calculations based on data from CENSIDA.

How Do Community-Based Organizations in the Northern Border Deal With Cuts in Public Funding?

The first austerity measure taken by these small community-based organizations is to stop paying salaries and work only with volunteers, which especially affects the peer workers[5] who support field activities, since professional staff usually have a second job which allows access to stable income. In most cases, peer workers who have family support can continue to support the activities of community-based organizations on a volunteer basis, while those who are heads of households see their participation in organizations much more restricted.

The second measure has been to reduce the hours and days they are open. In addition, the number of syringes, sterile water, and HIV tests distributed has been decreased, with the idea of riding out the crisis as much as possible, waiting for an exit that today remains unseen. With these measures, it is the population of people who inject drugs who are left to their fate, since there are no people to cure them, accompany them to health services, and give them new syringes.

Other organizations have resorted to asking for a recovery fee for the services they provide, which raises suspicions in some users, while others simply stop coming because they cannot afford the fees. There are also parties, raffles, and sales of posters and promotional materials to finance some of their activities, but the money collected is insufficient compared to the logistical efforts that these activities demand. This situation is unsustainable and jeopardizes the Sustainable Development Goals, which includes ending the HIV epidemic by 2030 and was signed by Mexico, “a country of rapid boom and slow compliance.”

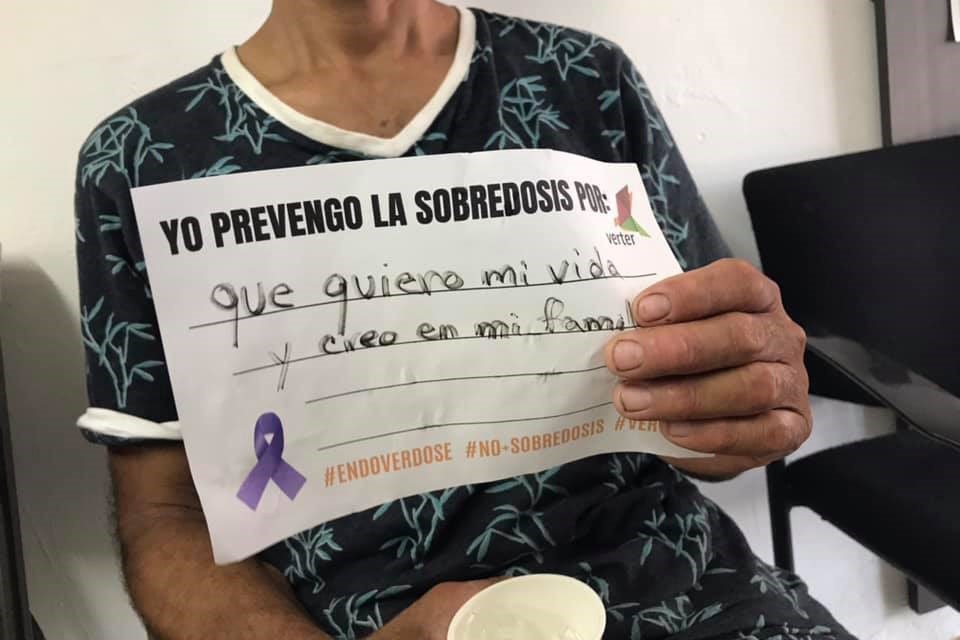

The field experience of the organizations and people that belong to the Mexican Network of Harm Reduction (Spanish acronym REDUMEX), and that implement actions in the most remote places of the republic, has taught us that — contrary to the prejudices sustained by physicians, psychologists, and psychiatrists — people who use drugs, even those who inject heroin and crystal meth daily and live in the shooting halls, want to take care of their health, want to get tested for HIV, and want access to treatment to control their serological levels and hepatitis. However, they do not find support to adhere to treatments or access to supplies that allow for safer drug use practices. The author’s experience in Tijuana, Hermosillo, Mexicali, and Ciudad Juarez has shown that it is the daily accompaniment from a place of solidarity and empathy, where they are treated as any other human, providing listening, smiles, and hugs that leads to treatment adherence, and not just a medication scheme or hospitalization in the centers. It is community organizations and peers, who have built knowledge for about three decades, who go to the “picaderos” (shooting halls) several times a week, talk to people who inject drugs, and engage them in caring for their health. That cumulative experience is today at risk and, because of it, we need a public policy of harm reduction.

Due to the end of HIV funding, financing for harm reduction is undergoing a crisis, which puts us in the urgent position of fighting for a federal harm reduction policy that puts the health issues of people who use injected and noninjected drugs at the center. Drug use should not remain a barrier to accessing rights, as it is now. Before reaching treatment for drug dependency, users need truthful information about the drugs they use and how to reduce the risks associated with their use, as well as technologies to test their drugs and medications so as not to die from overdose. There is clearly a missing link between prevention and treatment, and we can find this link in harm reduction.

The turn in the narrative against drugs that the current president of Mexico has proclaimed requires putting drug users at the center and, in order to do this, the public funding of community-based organizations that have years of experience is indispensable.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Angélica Ospina-Escobar is a fellow at the Rockefeller Institute of Government, an assistant professor in the Drug Policy Program at Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económica (CIDE), Región Centro, and a member of the Mexican Harm Reduction Network (Redumex).

[1] Marisol Valenzuela-Lara et al., Impacto del financiamiento de programas de reducción del daño para personas que se inyectan drogas en México. Salud Mental 42, 4 (Forthcoming).

[2] There are no data for year 2015.

[3] There are no data for year 2015.

[4] There are no data for year 2015.

[5] Peers workers are active or former drug users who belong to the community where the implementation takes place. They are key for harm reduction interventions, not only because they operate as gate keepers, facilitating confidence between the community and the professional staff, but also because they help to build the capacity of the population of injecting drug users in making health-enhancing life choices and empower them by providing evidence-based drug information in their language, that helps to recognize and address dangerous behaviors and unhealthy attitudes. In this sense, peer workers are influencers within the social networks of people who inject drugs as they have relevant skills (overdose prevention, CPR techniques) and provide informal support to their peers as well as access to health supplies and facilities. Informe Nacional de Avances en la respuesta al VIH y el Sida: Periodo reportado: Enero-Diciembre 2014, Fecha del informe: abril 2015 (México City: CENSIDA, 2015), https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/26534/GARPR_Mx2015.pdf.

READ THE SERIES

The Rockefeller Institute’s Stories from Sullivan series combines aggregate data analysis with on-the-ground research in affected communities to provide insight into what the opioid problem looks like, how communities respond, and what kinds of policies have the best chances of making a difference. Follow along here and on social media with the hashtag #StoriesfromSullivan.