“How do you sustain a community where kids are no longer with parents?”

— Sullivan County official on the effects of the opioid crisis

Overview

Adults may be the ones using drugs, but children are the opioid epidemic’s greatest collateral damage. In Sullivan County, we’ve heard stories of loss — of parents losing their children to drugs, but also of children losing their parents. We’ve heard of children witnessing their parents’ deaths and witnessing their parents being revived, sometimes multiple times. Of children being separated from their families and from their communities.

Children of parents with substance use disorders are at an increased risk of experiencing maltreatment.[1] The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has estimated that rising rates of drug-related hospitalizations and drug overdose deaths are related to rising child welfare caseloads — an increase of 10 percent in a county’s drug-related hospitalizations and overdose death rates has been estimated to lead to an increase in foster care placement rates of 2.9 and 4.4 percent, respectively.[2]

After a decade of out-of-home placement reductions, the US foster care population has been growing, from 396,966 in 2012 to 437,465 children in out-of-home care during 2016, an increase that has been attributed, mostly anecdotally, to the opioid crisis.[3] Researchers have estimated the number of children removed because of parental substance or alcohol abuse rose from 14 percent to 34 percent between 1998 and 2016. Roughly 35 percent of children whose parental rights were terminated in 2012 had been removed for parental alcohol or drug abuse.[4]

The consequences for children might be even more acute than in prior drug epidemics. Opioid dependency among adults living in households with children is increasing. In fact, 40 percent of new opioid-dependent adults are estimated to live in households with children.[5] Moreover, parents involved in the child welfare system who use opioids are less likely than other drug users to retain custody of their children.[6] Finally, there has been a substantial increase during the past fifteen years of in utero exposure to opioids in mothers involved in the child welfare system.[7]

The consequences for children might be even more acute than in prior drug epidemics. Opioid dependency among adults living in households with children is increasing. In fact, 40 percent of new opioid-dependent adults are estimated to live in households with children.

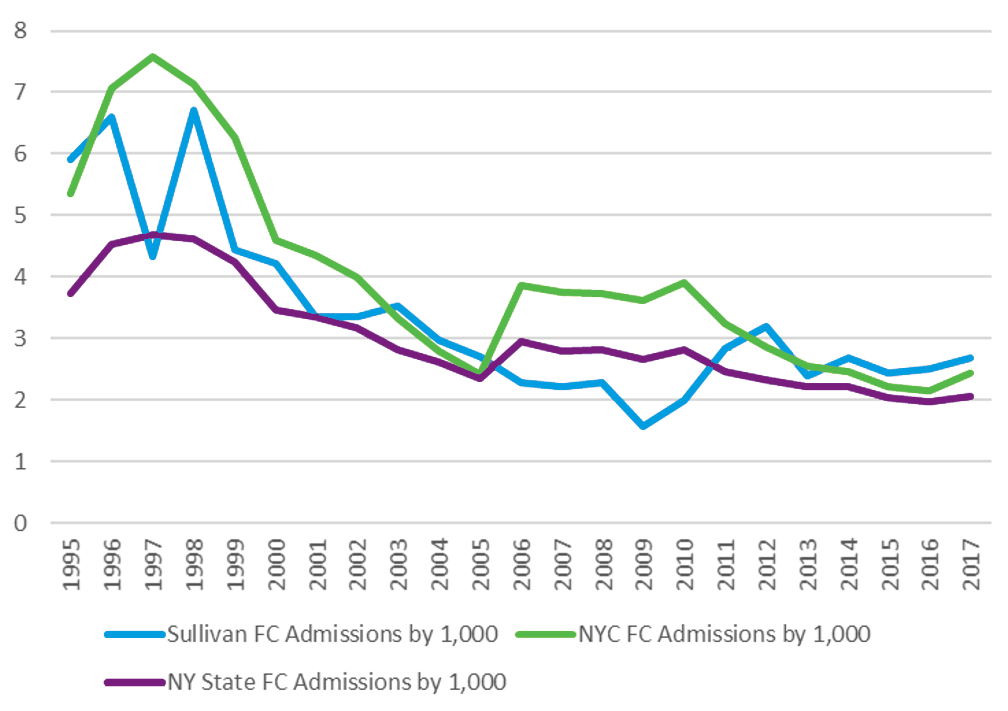

Although, nationally, drug overdose hospitalizations and drug overdose deaths are related to increased child welfare caseloads and although, nationally, people on the frontlines (judges, caseworkers) describe a sharp increase in foster care placements due to opioids, we do not have solid data that demonstrate it. In New York State, the overall number of children in foster care has dropped significantly between 1995 and 2017. So, what can the numbers tell us? What happens to children during the opioid epidemic? What is the potential impact on foster care and, more importantly, what impact does foster care have on children?

The Relationship between Drug Use and Foster Care Placements

Numbers do not lie, but they may not necessarily tell the whole story either. Mark Courtney, a University of Chicago expert on foster care, suggests that we can learn lessons about the effect of opioids on foster care by looking at previous drug epidemics. Looking at the past shows that there is not a direct correlation between drug use and foster care. Instead, how county officials, families, and judges respond to parents who use drugs determines how many children are placed into foster care, how many homes are available to care for them, and how much all of this will cost the county.

First, how county officials respond to drug use will have an impact on foster care numbers. Approximately one in five children entering foster care are infants. Counties in New York State have a great deal of leverage in how they treat mothers who give birth to children with opioids in their system. Screening mothers and their babies for the presence of opioids and treating positive tests as evidence of child abuse or neglect — as was often the case with crack cocaine — will result in much higher foster care placements.

Second, the availability of other family members to provide foster care for children will have an impact on foster care placements. During the late 1980s and early 1990s, crack cocaine strained the foster care system, leading to placements with family rather than unrelated foster homes. Although biological families are supposed to be paid like other, unrelated foster families, they sometimes serve as guardians unofficially or in exchange for benefits for the children, like TANF, Medicaid or food assistance, or electronic benefits transfer (EBT).

Third, how courts view opioid use can have a significant impact on foster care placements, too. Judges have authority to place children in the care of another family member and to demand evidence-based high-quality treatment. Judges can also take children away from their parents and place them in foster care with an unrelated family, having a potentially huge impact on foster care numbers (and a county’s budget).

The Costs of Foster Care

Foster care generally is very costly: it strains county budgets; it has lifelong effects on children who are a part of the system; and it tears apart the fabric of communities.

Foster care strains county budgets. The costs of foster care provision are substantial, running about $21,535 per year for each child in a regular foster care placement, and up to $81,441 for institutional placements (FY 2011 estimates). The average annual cost of placing a child in foster care in New York State is $51,943 (in FY 2017), which is more expensive than tuition at Harvard.

Foster care generally is very costly: it strains county budgets; it has lifelong effects on children who are a part of the system; and it tears apart the fabric of communities.

But, unlike Harvard, where students get the benefit of high spending in a rewarding experience, money barely trickles down to children in foster care. Monthly payments (to foster families or homes) in Upstate New York ranges from $552 for infants to $2,016 for children with conditions such as HIV.

Foster care also has far-ranging, long-term social costs and lifelong consequences for children. Children in foster care are an extremely vulnerable population. They are at higher risk for experiencing adverse life outcomes, such as homelessness, higher rates of teenage pregnancy, and lower earnings.[8] Additionally, children in foster care are more likely to drop out of school and to experience substance abuse problems themselves.[9] They exhibit higher rates of behavioral, emotional, and health problems, which not only result from the experiences that led to their placement, but from the experience of the foster care system itself.[10]

An Increased Number of Placements, Different Types of Placements, or Both?

A recent ASPE Research Brief found that people in communities on the frontlines perceive the number of children in foster care as increasing due to opioid use in their families and believe it is more difficult to find placement for these children, echoing our own interviews in Sullivan County.[11] Officials in Sullivan County identified the family and child welfare services, in particular, as one of the areas that has been hardest hit by the far-reaching “tentacles” of the opioid crisis. They expressed not only concern, but alarm, regarding the devastating effect that the epidemic was having on families; on the family structure; and, ultimately, on the county’s social fabric. One official noted communities are going from “single parent families, to no parent families.”[12] If something is not done, he warned, “you are not going to have a family structure at some point in the next decade … kids aren’t going to have even just single parents any more, it’s going to be foster parents or being placed in a facility for their … younger ages.”[13]

Communities on the frontlines perceive the number of children in foster care as increasing due to opioid use in their families and believe it is more difficult to find placement for these children.

Officials explained how county expenditures for child protective services and foster care have sky-rocketed. According to data from the Sullivan County budget, county foster care costs have nearly tripled, from $551,895 in 2017 to $1,592,895 in 2018, while federal funds for foster care decreased from $1,550,000 to $1,300,000 during the same period. Although capped funds allocated to Sullivan County through the state’s Foster Care Block Grant increased between 2017 and 2018 by $111,008, the brunt of rising costs falls to the county or, as one public official put it: “[O]nce you’ve hit your cap, you’re done. So if you have a hundred kids and that’s your cap, and all of a sudden you have 200, that’s all local cost, there’s no other federal, state money for that.”[14] In addition to the financial costs of counties, local officials talked about the increased complexity and severity of the cases, including babies being born with drugs in their system and having to remove them “directly as newborns and a couple of days old.”

| 2017 | 2018 | % Change | |

| Sullivan County foster care costs | $551,895 | $1,592,895 | 188.62% |

| Federal funds for foster care | $1,550,000 | $1,300,000 | -16.13% |

Source: Sullivan County budget

It wasn’t clear at the start of the epidemic that the effect on children would be so dramatic. But local officials describe this threat to the community’s social fabric as “eye-opening.” It “kind of made it more real, not that it wasn’t real, but it kind of made it more that this is really, really getting serious now … it magnified the issue locally for us. And it’s not just the budget, I mean, we can deal with the numbers. But I think it became the social fabric of the community … how do you sustain a community where kids are no longer with parents?”[15]

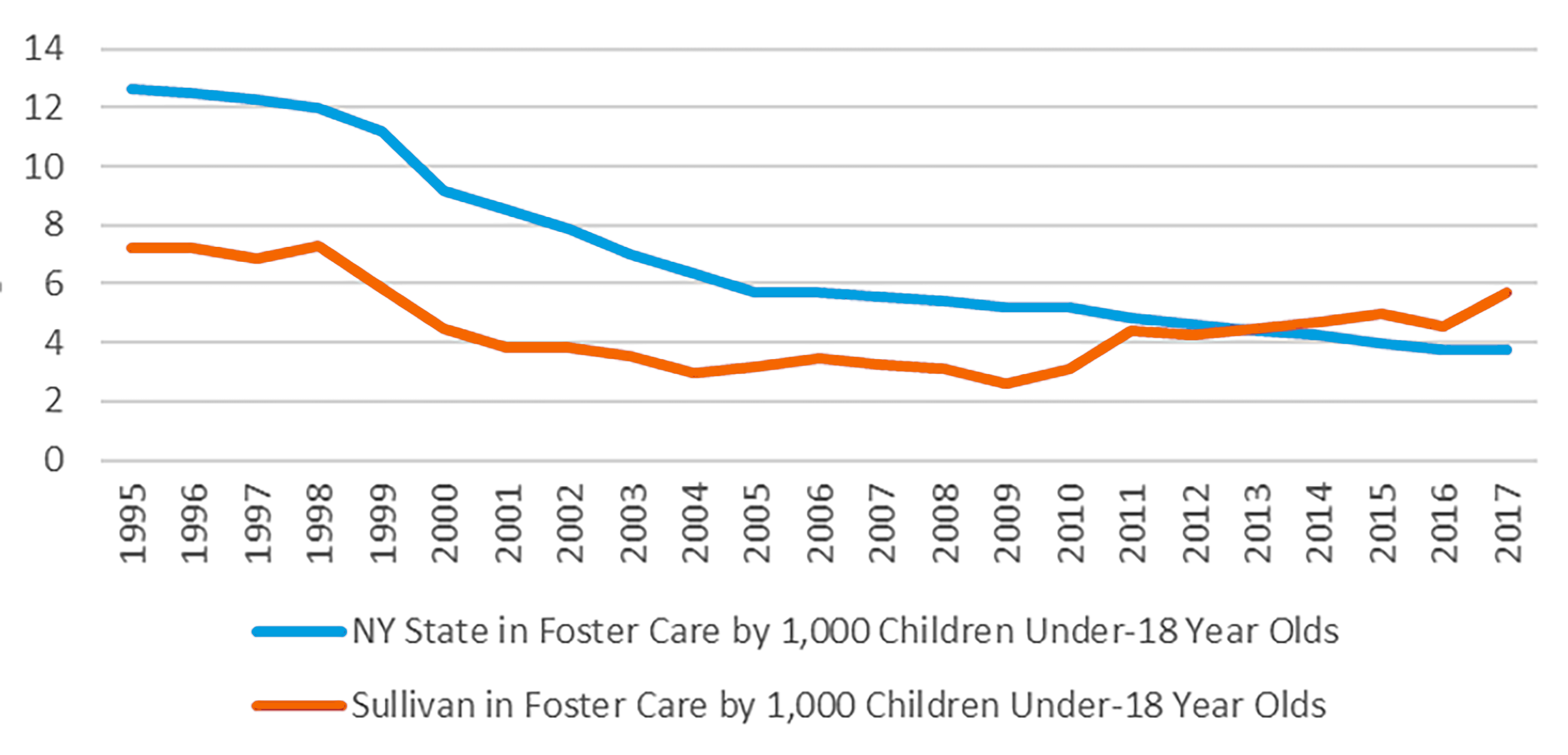

The number of children in foster care in the state of New York has decreased overall, from 37,000 in 2003 to 17,500 in 2017, but places like Sullivan County, which are hardest hit by the opioid epidemic, say they are seeing an increase and intensification of cases. Foster care numbers in Sullivan have been ticking upwards since 2009.

According to officials, the general scarcity of resources for addiction services, for mental health services, and for family and child services, coupled with the small number of foster care providers in the county, and its large geography, have resulted in increased numbers of children placed into foster care in the last two years. In 2017 alone, forty-seven children entered foster care in Sullivan County, with 100 children in foster care on the last day of 2017: a rate of 5.7 per 1,000 children under the age of eighteen, higher than the statewide rate of 3.7.

Rates of Children in Care on the Last Day of the Year, 1995-2017

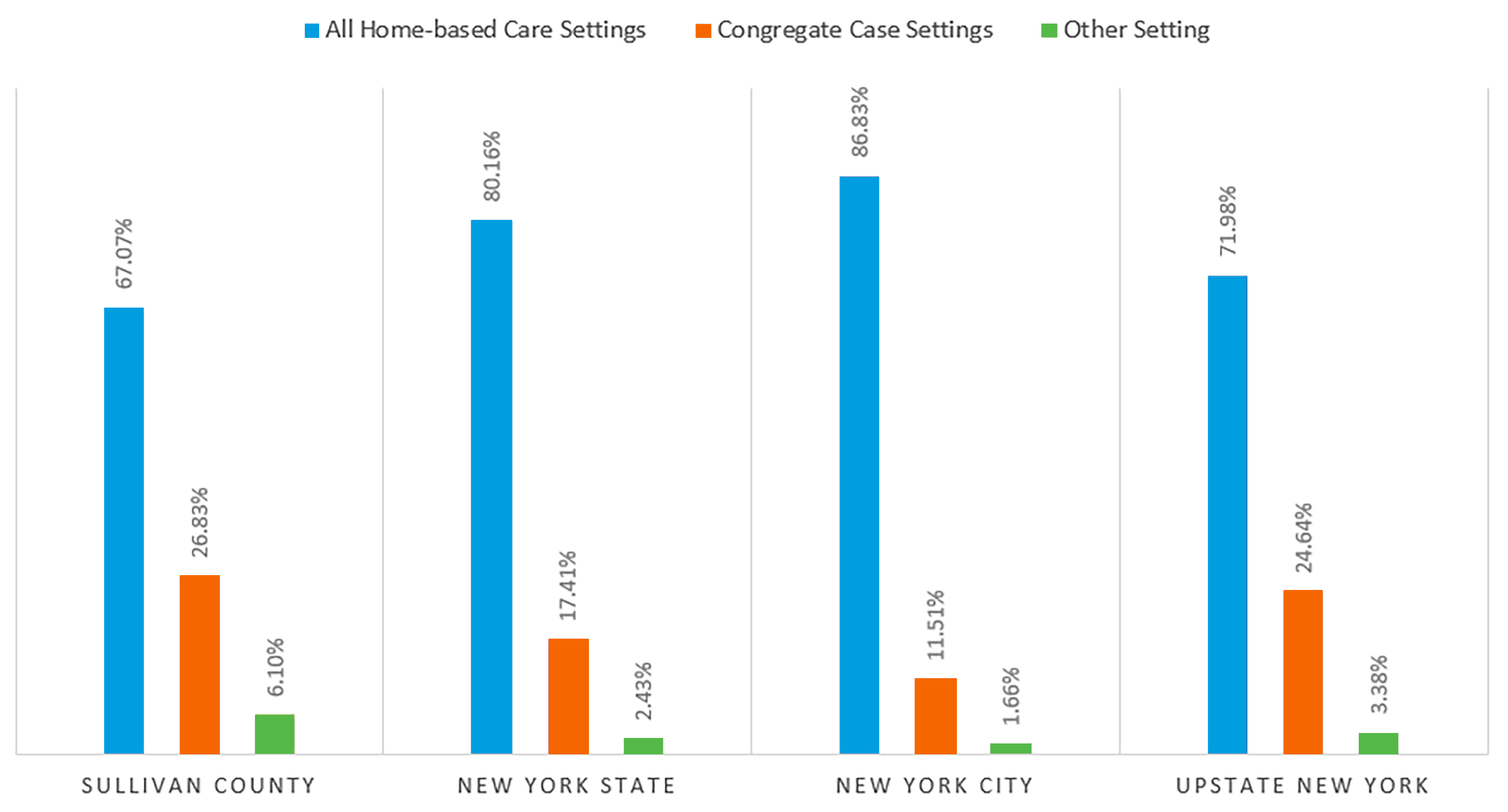

In addition to the increased rate in both foster care entries and children in foster care, there have been changes in the type of placements, which may account for the increased costs experienced by the county. In 2017, Sullivan County children spent 34,438 days in foster care; only 1.5 percent of the days were in approved relative homes, the least costly type of placement, while 60.9 percent were in foster boarding homes and 22 percent in institutions, which are the costliest type of placement. By comparison, in 1995, more children were placed in relatives’ homes (4.8 percent), more children were placed in foster boarding homes (80 percent), and fewer were placed in institutions (9.8 percent).

In general, Sullivan County children are placed more often in group-home settings. For example, of the eighty-two Sullivan children in care on the last day of 2016, two-thirds (55) were placed in home-based care settings, like placement with relative or in foster care; a quarter (22) were placed in congregate care settings, like group homes; and one in twenty (5) were placed in other settings. In comparison, the percentage in home-based-care settings at the statewide level was much higher, and congregate care (institutions) and other settings were lower.

Percent of Children Living in Foster Care by Setting Type on December 31, 2016

Children in Sullivan County are also spending more time in foster care. In 2017, they spent an average of 269 days in foster care, the highest number in our data (in 1995, the average was 208, and the lowest during the 1995-2017 period was 177 in 2005).[16]

They are also being placed out of Sullivan County. Even though county officials “try like hell” to keep children in their communities, more children are being placed out of county and even out of state. Nationally, the ASPE research reports difficulty in finding foster homes because children are in care longer (keeping existing foster homes full), in placing siblings together, and in finding local placements. Multigenerational substance use may also play a role in finding family members to take in children.[17] As a Sullivan County official explained, “[I]n our case, we don’t really have a lot of foster care providers, so they are getting shipped to Pennsylvania, Massachusetts. So it’s really almost destroying, in some respects, the whole family structure. The kids are just, they’re not … even if they are fostered in the county they are being fostered hundreds of miles away somewhere.”[18]

Even though county officials “try like hell” to keep children in their communities, more children are being placed out of county and even out of state.

Of the total Sullivan County children in foster care during 2016 (132), 40 percent (53) were placed out of county and 2 (1.5 percent) were placed out of state. This has serious repercussions in terms of the possibility of achieving family reunification, which often depends on the availability of intensive family-centered services, and increases the probability of children lingering in the foster care system for prolonged periods of time. It further increases the trauma that often characterizes the foster care experience, causing total disruption in the child’s life — loss of parents, friends, and community.

Foster care is not only disruptive, it can also be unsafe. The rate of indicated maltreatment reports while in foster care for children in Sullivan County was 19.22 (per 100,000 care days), higher than the statewide rate of 15.93, and the Upstate rate of 13.8. Foster care is designed to be a measure of last resort and, often, a life-saving intervention. Nonetheless, the effects of receiving poor foster care services can be harmful to children, families, and communities; for children to experience maltreatment while in the foster care system is a massive failure of our foster care system.

What Communities Say They Need

When specialized care is needed — to treat substance-use disorders, to provide for the mental health of children in families affected by substance-use disorder, or finding families/facilities to place children — already scarce local resources may be stretched too thin. In rural areas there is a small pool of potential foster families to begin with. Unlike their urban counterparts who have resources to scale, rural communities cannot build group homes to house children who need care. The irony is that rural counties, with few resources, may end up paying more: housing children in group homes because they can’t find foster families and housing them out of county because they don’t have the ability to place them closer.

As one Sullivan County official explained when asked about the resources they needed, “… I guess more funding for foster care, because if we can’t, if we are not going to create beds or create more places to put people, we need more funding to kind of help place kids as their parents are having issues.” He further explained that if the opioid problem was effectively addressed, the strain on the foster care system would be reduced.

There is a need for increased specialized resources to address the trauma that families and children suffer as a consequence of parental substance abuse, including social workers and mental health professionals. Current personnel on the frontlines say they are overwhelmed with high caseloads and insufficient resources to address the needs of this population. And, more importantly, there is a need for good in-county foster homes to provide a loving and supportive environment for children to heal and thrive; to give the child’s life a semblance of stability and normalcy. As one county administrator noted:

If I’m taking a child out of a home, I want to make it as normal as possible for them in that transition, and, you know, kids go to birthday parties, they have sleepovers, they go out to Chuck-e-Cheese. That doesn’t happen in a lot of our foster cares, I’m not saying in all of them. But again, they also live on limited resources and are taking in kids out of the goodness of their heart and giving them a safe home. So, I’m not knocking them. But sometimes it’s just — it needs more than just a safe home, to feel normal.[19]

Conclusion

Even though adults are the ones with substance-use disorders, a closer look at foster care suggests that children may be paying the price. Foster care is expensive and — even with good placements — the effects can be far-reaching. Experts do not know whether the disconnect between national data, which does not show a sharp and sudden spike in foster care placements, and interviews with local officials, who say that they are overwhelmed, is due to a lag in the data (the reporting hasn’t caught up to the reality) or if there is something else going on, such as a similar number of children in foster care but more difficulty in finding suitable placements for them. A closer look at Sullivan County shows just how far-reaching the problem can be.

If you are interested in becoming a foster or adoptive parent in Sullivan County, please contact the Sullivan County Department of Family Services at (845) 292-0100 ext. 2292 or (845) 292-0100 ext. 2389.

Foster Care Admissions per 1,000 Under-Eighteen Year Olds

NOTES

[1] Linda C. Mayes and Sean D. Truman, “Substance Abuse and Parenting,” in Handbook of Parenting, Volume 4: Social Conditions and Applied Parenting, ed. Marc H. Bornstein (Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2002); Rebecca G. Mirick and Shelley A. Steenrod, “Opioid Use Disorder, Attachment, and Parenting: Key Concerns for Practitioners,” Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal 33, 6 (2016): 547–57.

[2] Laura Radel, et al. : Key Findings from a Mixed Methods Study, ASPE Research Brief (Washington, DC: Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, March 7, 2018), https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/258836/SubstanceUseChildWelfareOverview.pdf

[3] Cory Morton and Melissa Wells, “Behavioral and Substance Use Outcomes for Older Youth Living With a Parental Opioid Misuse: A Literature Review to Inform Child Welfare Practice and Policy,” Journal of Public Child Welfare 11, 4-5 (2017): 546-67, https://chhs.unh.edu/sites/chhs.unh.edu/files/departments/social_work/morton_wells_jpcw-opiate-child-outcomes.pdf; NK Young, “Examining the Impact of the Opioid Epidemic. Testimony before the United States Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs. Lake Forest, CA: Children and Family Futures,” 2016, www.hsgac.senate.gov/download/testimony-young-2016

[4] Only higher for children removed for neglect (Sid Gardner, State-Level Policy Advocacy for Children Affected by Parental Substance Use (Lake Forest: Children and Family Futures, August 2014), http://childwelfaresparc.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/State-Level-Policy-Advocacy-for-Children-Affected-by-Parental-Substance-Use.pdf; “Number of children in foster care continues to rise,” Administration for Children & Families (ACF), November 30, 2017, http://www.acf.hhs.gov).

[5] L.R. Bullinger and C. Wing, “Trends in opioid abuse and dependency in households with children,” unpublished paper, 2017.

[6] Martin T. Hall et al., “Medication-Assisted Treatment Improves Child Permanency Outcomes for Opioid-Using Families in the Child Welfare System,” Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 71 (December 2016): 63-7.

[7] Gregory Bushman et al., “In Utero Exposure to Opioids: An Observational Study of Mothers Involved in the Child Welfare System,” Substance Use & Misuse 53, 5 (2017): 844-51.

[8] Mark E. Courtney, Sherri Terao, and Noel Bost, Midwest Evaluation of the Adult Functioning of Former Foster Youth: Conditions of Youth Preparing to Leave State Care (Chapin Hall Center for Children at the University of Chicago, 2004), http://www.tndev.net/mbs/docs/reference/Transitioning_Youth/Midwest_Study_Former_Foster_Youth.pdf; Joseph J. Doyle, “Child Protection and Child Outcomes: Measuring the Effects of Foster Care,” American Economic Review 97, 5, December 2007: 1583–1610.

[9] Mark E. Courtney et al., Foster Youth Transitions to Adulthood: Outcomes 12 to 18 Months After Leaving Out-of-Home Care (Madison: School of Social Work, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1998).

[10] Scott Cunningham and Keith Finlay, “Parental Substance Use and Foster Care: Evidence from Two Methamphetamine Supply Shocks,” Economic Inquiry 51, 1 (2013): 764-82; Doyle, “Child Protection and Child Outcomes.”

[11] Radel et al., Substance Use, the Opioid Epidemic, and the Child Welfare System.

[12] Interview #11_12012017.

[13] Interview #23_03152018.

[14] Interview #23_03152018.

[15] Interview #23_03152018.

[16] “Monitoring and Analysis Profiles (MAPS), Aggregate Data,” New York State Office of Children and Family Services, accessed August 6, 2018, https://ocfs.ny.gov/main/reports/maps/defaultAgg.asp

[17] Radel et al., Substance Use, the Opioid Epidemic, and the Child Welfare System.

[18] Interview #23_03152018.

[19] Interview #19_01182018.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Elizabeth Pérez-Chiqués is a research assistant at the Rockefeller Institute of Government

Patricia Strach is the deputy director for research at the Rockefeller Institute of Government

Katie Zuber is the assistant director for policy and research at the Rockefeller Institute of Government

SUGGESTED CITATION

Elizabeth Pérez-Chiqués et al., “The Other Family Separation Crisis,” Rockefeller Institute of Government, August 8, 2018, https://rockinst.org/blog/stories-from-sullivan-the-other-family-separation-crisis/.

READ THE SERIES

The Rockefeller Institute’s Stories from Sullivan series combines aggregate data analysis with on-the-ground research in affected communities to provide insight into what the opioid problem looks like, how communities respond, and what kinds of policies have the best chances of making a difference. Follow along here and on social media with the hashtag #StoriesfromSullivan.