As part of our Stories from Sullivan series, we talked to experts across the border in Mexico to understand what the opioid epidemic looks like there, and how their government addresses opioid dependency. In this analysis, Professor Angélica Ospina-Escobar shows what opioid dependency looks like in Mexico and how policies in Mexico that limit access to methadone harm treatment and recovery efforts.

Tan Lejos de Dios, y Tan Cerca de los Estados Unidos

“So far from God and so close to the United States,” is a phrase that is repeated in Mexico to express how the social, economic, and health crises facing the United States have a counterpart in Mexico. What is the Mexican correlate of the opioid crisis in the United States? Has the prevalence of heroin use changed over time? Are we facing a future scenario of over-mortality in people dependent on heroin due to the presence of fentanyl?

When examining the data available in the National Epidemiological Surveillance System of Addictions, it turns out that these official data on drug use in Mexico do not allow us to outline a clear trend regarding heroin use in the country. For example, national addiction surveys show that while in 1988 the national prevalence of once-in-life heroin use was 0.01 percent, in 2011 it rose to 0.2 percent, remaining at that level until 2017, the date of the last national survey of drug use.[1] On the other hand, the National Survey on Drug Consumption in Public Primary, Secondary and High School Students[2] reports a prevalence of heroin once in life use among young people between 12 and 19 years old of 0.9 percent, which suggests an increase in heroin use in the juvenile population.

The data available from public addiction treatment centers, however, show decreasing trends in the volume of people seeking treatment for the problematic use of heroin. Thus, while in 1994 the percentage of people seeking help for heroin dependence was 13.3 percent, in 1999 it fell to 8.8 percent; in 2007 it was 10.5 percent and for 2016 the proportion was 3.4 percent. It is noteworthy that while in the 1990s only the northwestern region of the country reported cases of problematic heroin use, as of 2005 it is a situation reported in all 32 states of the Mexican Republic.

A heroin user in a buying-selling-using location in Hermosillo, Sonora. (All photos by Angélica Ospina-Escobar.)

With respect to the trajectories of drug initiation, from the total of individuals receiving in-patient services in non-governmental treatment centers from 1994 to 2016, only between 1 and 7 percent reported heroin as a starting drug. Regarding drug-related mortality, deficiencies in the mortality data do not allow for the accurate identification of drug-related deaths, nor for the accounting of changes in drug-related mortality over time. In general, the mortality reported by official sources of heroin overdose in Mexico is around 0.1 percent and has remained relatively stable at that level for about two decades. In contrast, violence consistently appears as the leading cause of death in this population. Which means that what kills people dependent on heroin in Mexico is not the substance itself, but a hostile context that discriminates and marginalizes this population.

By 2015, it was estimated that there were 141,690 opioid users in the country.[3] Of these, 44 percent were concentrated in the cities of Tijuana, Ciudad Juárez and Hermosillo. The states of Baja California — whose capital is Tijuana — and Chihuahua, where Ciudad Juárez is located, are the states with the highest prevalence of heroin use nationwide as reported in 2017 (0.3 percent and 0.2 percent respectively).

These data suggest that Mexico is far from having epidemic levels of problematic heroin use and that it is rather a situation concentrated in specific regions of the country. In this scenario, offering systems of care to users with problematic heroin use in cities with a higher prevalence of consumption would be an efficient and cost-effective strategy to not only provide treatment and expand health care to this population, but also prevent the emergence of new consumers and collect epidemiological data on the trajectories and dynamics of drug use, as well as the health conditions of this population. Additionally, establishing systems of care would aid in further exploration of the local drug markets. This would improve the ability to monitor the appearance of new substances such as fentanyl and its effects on the health conditions of populations with problematic drug use and their buying-selling-using dynamics.

Given the emergence of the opioid crisis in the United States, the adjustment of better mechanisms for epidemiological surveillance of drug use is necessary in Mexico. This means having better and more expansive approaches to user populations from a human rights perspective. Politically, this means that we must begin to consider drug users as members of society regardless of their drug use.

A needle-exchange program in Mexicali, Baja California. For each used syringe that is delivered, 10 new syringes are given in exchange. This harm-reduction measure removes used syringes from circulation, decreasing the propensity to use them, and cleaning the streets of contaminated material.

The Malilla: The Opioid Crisis and the Intentional Policy of Pain in Mexico

The malilla [slang Spanish word for withdrawal syndrome] is the worst thing that can happen to you, I really do not wish it upon anyone, not even my worst enemy. You tremble, your belly becomes a knot, you can’t pass anything, not even water. Your bones hurt, you can’t walk, nor think, nor sleep, from the pain you feel, you only think about having a fix [using heroin]. You sweat nonstop, everything turns around and in addition, you suffer from insomnia… It’s… It’s really uncontrollable, it’s something very strong, very, very “gacho” [bad, ugly]. That’s why when you want to break away from the Shiva [heroin], you need something to help you. That’s why we turn to methadone. The problem is that, if you stop taking the methadone, it also hits with withdrawal symptoms, the same or even worse as with the Shiva, there is no way out…

— Ivan, 35 years old, Hermosillo

Paco has been heroin dependent since he was 15 years old. At 19, after several admissions to treatment, he began a substitution treatment with methadone

Methadone is the only medication available in Mexico that can treat the symptoms of opioid withdrawal syndrome. This syndrome is a physiological response to the cellular adaptations of the permanent stimulation that opioids generate in the central nervous system. The intensity and severity of the symptoms depend on the type and amount of substance consumed. In the first phase, symptoms include piloerection, heavy sweating, generalized pain, muscle spasms, bone pain, tachycardia, hypertension, tremors, irritability, motor agitation, anorexia, and insomnia. At an advanced stage, symptoms include paresthesia, fever, colicky abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and hyperglycemia.[4] It is medically acknowledged that opioid withdrawal syndrome can cause death.

Using methadone does not necessarily mean that people struggling with opioid addiction stop using drugs, but it is a harm-reduction strategy that helps decrease the frequency and intensity of heroin use and, with this, people manage to better perform their roles within their families, jobs, schools, etc. Additionally, it is an effective measure to reduce the risks of HIV infection, Hepatitis C, and death from an overdose.

Thanks to methadone, Paco had found a job in a grocery store near his house, with which he financially supported his two daughters and his partner. Under methadone treatment, Rosario, a street resident in Mexico City with HIV and a dependence on heroin, achieved adherence to antiretroviral treatment. Thanks to that, she had reached viral suppression in December of last year. That is to say, Rosario not only enjoyed excellent health conditions, but, having an undetectable level of HIV in her system, she also did not transmit the virus to other people. Through the services of the Condesa Clinic, the public HIV clinic in Mexico City, Rosario had also managed to access a temporary shelter system and hold temporary jobs, all of which contributed to the improvement of her health conditions.

Although methadone can be used successfully to treat opioid-use disorder and decrease the spread of infectious diseases, the government limits its usage, preferring an abstinence-based strategy. Limiting access to medication, however, can make drug use and disease worse, not better.

Lack of Medication

The government imposes limits on the production of the medicine itself. According to information available from the Comisión Federal para la Protección contra Riesgos Sanitarios [Federal Commission for the Protection against Sanitary Risks] (Cofepris), only one laboratory in the country is authorized to produce methadone, but it has restrictions on importing the supplies needed as raw material. According to an informant from this laboratory, importing these supplies can take up to nine months, once the corresponding permits have been granted. Once the raw materials enter the country and are transported to the laboratory, a civil servant from Cofepris must open the package. No one other than Cofepris personnel can open the package containing the raw materials, as these are classified as Schedule I controlled medications, which are the most restricted. These bureaucratic procedures in addition to a very limited demand for the product — given the small size of the heroin-dependent population in Mexico — makes methadone a low-priority medication, despite the suffering its absence creates in individuals suffering from opioid addiction.

Lack of Access

Although methadone is an essential medicine included in the basic supplies list of the health sector in Mexico since 2017, it is not available – except for honorable exceptions – in most public hospitals, so it is very difficult to access. And it is not available throughout the country. Only Tijuana and Ciudad Juárez have public clinics that offer methadone treatment. Along with these two public clinics, there are four private institutions that provide methadone treatment in Tijuana, Ciudad Juárez, Nogales, Mexicali, Nuevo Laredo, Zapopan, and Mexico City.

This focused provision of methadone treatment contrasts with the reports of the national surveillance system on drug use, which highlights the existence of heroin dependents in almost all the states throughout the national territory. It is noteworthy that while in the 1990s only the northwestern region reported cases of problematic heroin use, as of 2005 it is a situation reported in the 32 states of the Republic.

Even though the physical dependence generated by methadone is medically acknowledged, in recent years private clinics that offer this drug have been shutting down without following up on the people who were under treatment. In 2015, the methadone clinic in Hermosillo, Sonora closed. In 2017, two clinics were closed in Ensenada, Baja California, and in December 2018, the clinic in Mexico City was closed. In January 2019 the methadone clinics in Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, and Mexicali were declared in short supply and stopped providing the service. In all cases, the closure was made unexpectedly and there was no contingency plan to guarantee the welfare of the patients, some of whom had been in treatment for years.

Used syringes discarded on a street in a neighborhood north of Hermosillo, Sonora. Needle-exchange programs aim to take used syringes out of circulation to prevent exposure by non-user residents.

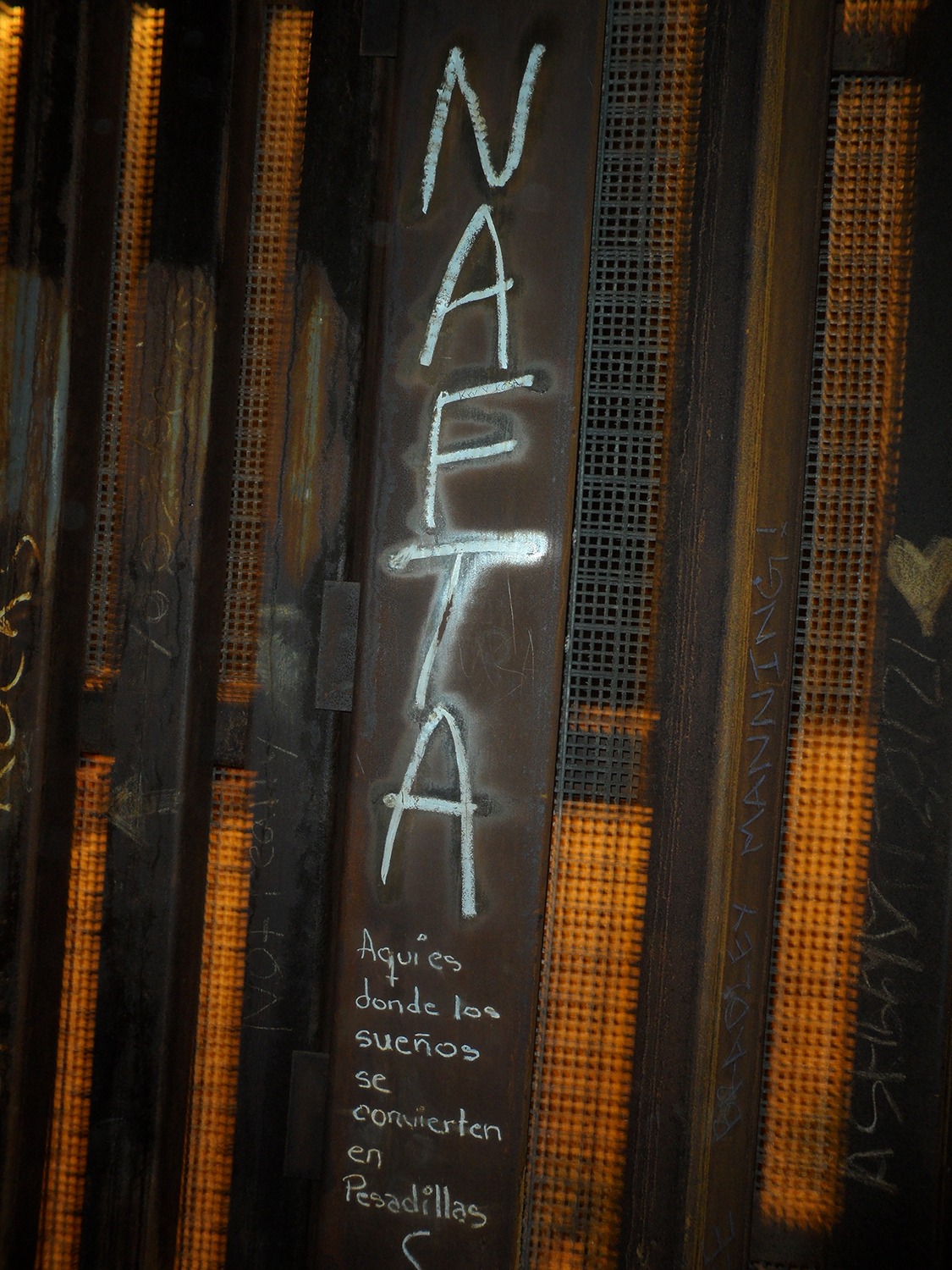

“Here is where dreams become nightmares,” border wall in Playas de Tijuana, Baja California.

Effects of Limiting Methadone

At first, patients like Paco and Rosario thought that the closing of the clinics where they received services would be temporary. In the past, the establishments would run out of the medication and be closed for a couple of days. However, this time the situation remains unsolved without any authority acting on the matter to ensure access to this essential medication

Given the physical dependence that methadone produces, its shortage exposes individuals to conditions of unnecessary suffering and constitutes a serious violation of their human rights. In the context of state indolence and faced with the severity of the malilla, the individuals return desperately to the use of injected heroin as a way of mitigating the physical pain caused by their dependence. This strategy will, in the long term, not only deepen their problematic drug use patterns, but also put them at greater risk of early death.

Thus, three years after the closure of the methadone clinic in Hermosillo and two years after the closure of the Ensenada clinics, the lack of services to the heroin dependent population continues. Anecdotally, we’ve heard of a spike in deaths, however, there are no official records.

Rosario has not returned to the Condesa clinic in Mexico City for her antiretroviral treatment; she has disappeared from the radar of those who were guiding her through her antiretroviral treatment and now they can only helplessly think that they lost a patient with an excellent prognosis, who will surely die anonymously in the cold streets of the city. Paco re-injected heroin two months after the closing of the Hermosillo clinic. Currently, he spends around $1,500 Mexican pesos [around $80 USD] daily to purchase the drug, an amount of money that guarantees the practice of illicit activities and the dismantling of his mother’s house. He lost his family and faces a precarious health situation, as his veins have collapsed, and he suffers from Hepatitis C. Paco isn’t the only one suffering from this dependence; his entire family, who watch helplessly as he deteriorates day by day, suffers too. This dependence affects two girls under the age of 10, who were left without a father, and his partner who, at 25, is now the head of the family.

Memorial for missing or murdered women in Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua.

Leaving the penitentiary of Hermosillo, Sonora, where many detainees are in for drug possession. The watchtower can be seen on the right side of the photo. There is no methadone program in the prison. On the other hand, when there is no heroin in the streets, the only place where you can buy it is in prison. Behind these transactions are many families who are trying to keep their loved ones alive.

The limited access to methadone can be understood as part of a state policy that privileges abstinence as the only treatment option for substance-use disorders in general, and heroin dependence in particular. This preference for abstinence programs is reflected by the ongoing methadone shortages and in the fact that no public entity has stepped up to ensure the supply of this medicine in the cities where private clinics have abruptly cut off their supply, thus leaving individuals who had been receiving services for their heroin dependence to their own fate at the mercy of the organized crime that controls the local drug markets.

In the case of heroin addiction, privileging abstinence as the only treatment option is denying the medical condition of withdrawal syndrome and subjecting people struggling with heroin addiction to unnecessary physical suffering. This denial of the public supply of methadone appears as a de facto policy in which the user is punished for his addiction, exposing him to pain. But pain does not cure dependence; on the contrary, pain dehumanizes and dishonors their lives and those of their families, and strips them of their dignity. In the end, once they have gone through this slow and painful process of social death, they will eventually die physically too, confirming the prophecy of “drugs = death.” However, it is not the drugs that kill; it’s the indifference of state institutions and the social stigma against drugs and drug users that ultimately seals their fate.

NOTES

[1] J.A. Villatoro et al., Encuesta Nacional de Consumo de Drogas, Alcohol y Tabaco (ENCODAT) 2016-2017: Reporte de Drogas (Ciudad de México, México: INPRFM, 2017).

[2] J. Villatoro-Velázquez et al., Encuesta Nacional de Consumo de Drogas en Estudiantes 2014: Reporte de Drogas (México, DF: Instituto Nacional de Psiquiatría Ramón de la Fuente Muñiz, 2015).

[3] Centro Nacional para la Prevención y el Control del VIH y el Sida (CENSIDA 2010), “Tamaño estimado de población HSH y UDIS en las ciudades prioritarias de propuesta Ronda 9.”

[4] F.J. Alzate García, “El síndrome de abstinencia por opioides,” Cuadernos de Psiquiatría, 49 (2012): 19-25.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

D. Ciccarone. “Heroin in brown, black and white: Structural factors and medical consequences in the US heroin market.” International Journal of Drug Policy 20(3) (2009): 277–282.

D. Ciccarone, and P. Bourgois. “Explaining the geographical variation of HIV among injection drug users in the United States.” Substance Use and Misuse 38(14) (2003): 2049-2063.

Ospina-Escobar, A., Magis-Rodríguez, C., Juárez, F., Werb, D., Bautista, S., Díaz-Carreón, R., Ramos, M.E., and Strathdee, S. “Comparing sociodemographic characteristics of people who inject drugs from three cities in Northern Mexico, their dynamics of drug use and risk environments for HIV.” Harm Reduction Journal Vol. 15, No. 27 (2018).

Secretaria de Salud, Sistema Nacional de Vigilancia Epidemiológico de las Adicciones, Informes 1998 – 2017, https://www.gob.mx/salud/acciones-y-programas/informes-anuales-sistema-de-vigilancia-epidemiologica-de-las-adicciones

US Customs and Border Protection, CBP Border Security Report Fiscal Year 2018 (2018), https://www.cbp.gov/sites/default/files/assets/documents/2019-Mar/CBP-Border-Security-Report-FY2018.pdf

US Customs and Border Protection, CBP Enforcement Statistics Fiscal Year 2019 (2019), https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/cbp-enforcement-statistics

Villatoro-Velázquez, J., Medina-Mora, M., Fleiz-Bautista, C., Téllez-Rojo, M., Mendoza-Alvarado, L., Romero-Martínez, M., Guisa-Cruz. Encuesta Nacional de Adicciones 2011: Reporte de Drogas. México DF: Instituto Nacional de Psiquiatría Ramón de la Fuente Muñiz; Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública; Secretaría de Salud, 2012.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Angélica Ospina-Escobar is assistant professor in the Drug Policy Program at Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económica (CIDE), Región Centro and a member of the Mexican Harm Reduction Network (Redumex).

Elizabeth Pérez-Chiqués, visiting fellow at the Rockefeller Institute of Government and member of the Stories from Sullivan research team, assisted with some translation.

READ THE SERIES

The Rockefeller Institute’s Stories from Sullivan series combines aggregate data analysis with on-the-ground research in affected communities to provide insight into what the opioid problem looks like, how communities respond, and what kinds of policies have the best chances of making a difference. Follow along here and on social media with the hashtag #StoriesfromSullivan.