The COVID-19 pandemic has shifted, among many other facets of life, the ways and places that people in New York State recreate. As family routines and state regulations necessarily changed over the course of 2020, some—particularly outdoor—recreational activities saw increased participation. While nascent trends, many outdoor recreational facilities, public lands, and state permitted activities and programs saw changes in use and enrollment. One such outdoor activity in New York was hunting.

On April 15th, in the midst of the pandemic, the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) announced that it was launching entirely online hunter education program course options. Enrollment in the program more than doubled over previous years. This research takes a closer look at both the longer-term trends in hunting education, participation, and license sales in New York, and in the United States more broadly, and considers those emerging trends in the context of COVID-19 and related programmatic responses.

Hunting is a critical wildlife management strategy and the collection of related fees is an important source of funding for conservation programming. The decades long decline in hunting participation in the United States combined with the current strain on public funding have threatened the long-term fiscal health of state and local level conservation efforts. It is, thus, important to understand the environmental and regulatory history of hunting, its relationship to conservation policy, and how current trends in participation compare to previous years.

History of Hunting and Conservation Policy in the United States

States rely on the sale of hunting licenses and participation in hunting as part of wildlife management and conservation strategies. In the early twentieth century conservationists and hunters, along with states and the federal government, sought to address the over-hunting of species and the large-scale destruction of key habitats, namely wetlands, through licensing and hunting restrictions as well as other policies.

The over-hunting and habitat loss in the United States at the end of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries particularly, but not exclusively, impacted migratory bird species. Consequently, a series of international treaties and federal laws and regulations were enacted. These included the passage of the Migratory Bird Conservation Act by Congress in 1929, which authorized the federal government to acquire wetlands and other bird habitats in order to permanently protect them. The Act did not, however, fund this land acquisition.

As a consequence, in 1934, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed into law the Migratory Bird Hunting Stamp Act, commonly referred to as the Duck Stamp Act. The Act required hunters 16 years old or older to purchase a Federal Duck Stamp in order to hunt waterfowl, and the sales of the stamps then supported the Migratory Bird Conservation Fund, which would in turn acquire land for the National Wildlife Refuge System. The reason that some permits like the Duck Stamp are referred to as stamps is that it is a literal stamp sold through the United States Postal Service and states for the purpose of permitting hunting.

The Duck Stamp Act served as a model for subsequent conservation funding and became part of what is referred to as the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation (US Fish and Wildlife Service). Perhaps the most notable successor of the Duck Stamp Act is the landmark Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Act, or the Pittman-Robertson Act of 1937. The Pittman-Robertson Act appropriated funds from a tax on sporting arms and ammunition to states[1] to support hunter education programs, wildlife management, and habitat restoration. This law has since been amended several times to expand the categories of arms taxed to include archery equipment and handguns, expand the programs funded under the tax, and apportion funds to the US territories.[2]

Trends in Hunting Participation

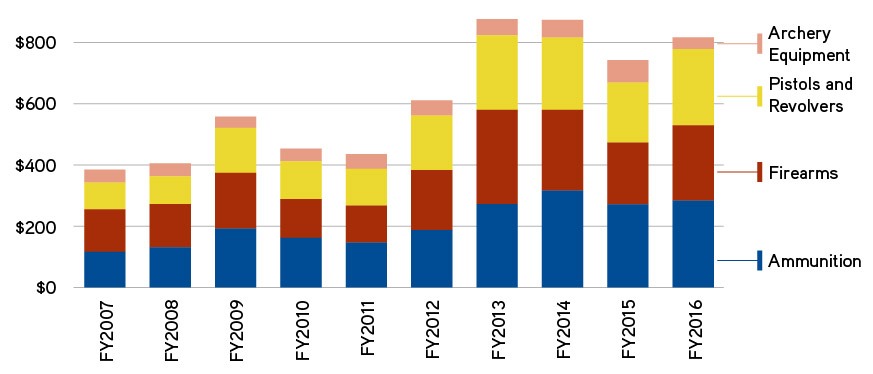

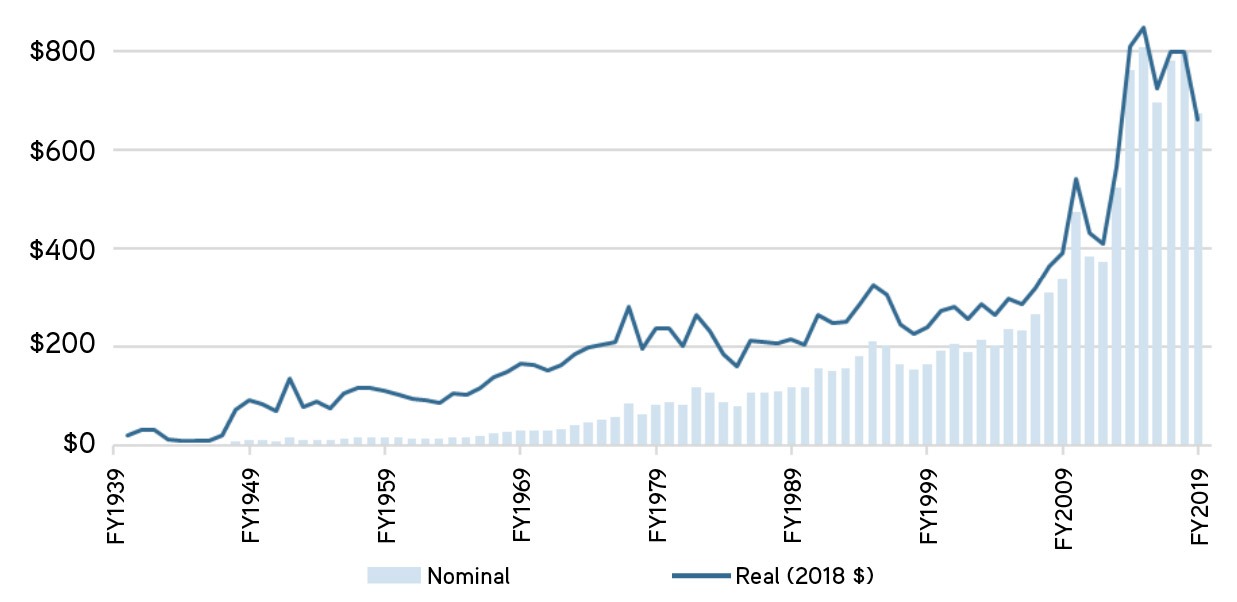

According to a 2019 report by the Congressional Research Service, the Pittman-Robertson Act has resulted in over $18.8 billion (2018 dollars) for states and territories. This funding has generally increased over time, particularly as firearms and ammunitions sales saw increased purchases over the last two decades. As recently discussed on the Rockefeller Institute’s Policy Outsider podcast, this trend of increased sales reflects the increased the number of firearms owned by the average household with firearms and not an increase in the number of registered gun owners.

Pittman-Robertson Revenues from Ammunition, Firearms, Pistols and Revolvers, and Archery Equipment, FY2007 – FY2016

SOURCE: Pittman-Robertson Wildlife Restoration Act: Understanding Apportionments for States and Territories (Washington: Congressional Research Service, April 5, 2019).

Pittman-Robertson Wildlife Restoration Act Total Apportionments,

FY1939 – FY2019

SOURCE: Pittman-Robertson Wildlife Restoration Act: Understanding Apportionments for States and Territories (Washington: Congressional Research Service, April 5, 2019).

Although the sale of sporting arms, archery equipment, and handguns, which all fall under the Pittman-Robertson Act, has generally increased in recent decades, sales of hunting licenses and participation in hunting has generally declined in the United States since the 1990s. The total number of hunters in 2015 according to the National Survey of Fishing, Hunting, and Wildlife-Associated Recreation was roughly 11.5 million. This is down from about 14.1 million in 1991. In contrast, the number of anglers (fishers) has not significantly changed since the early 1990s.

Hunting Participation in U.S., 1991 – 2016

| Year of National Survey | 1991 | 1996 | 2001 | 2006 | 2011 | 2016 |

| Hunters (in millions) | 14.063 | 13.975 | 13.074 | 12.510 | 13.674 | 11.453 |

| Percent of Total US Population | 7 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 4 |

SOURCE: 2016 National Survey of Fishing, Hunting, and Wildlife-Associated Recreation (Washington: US Fish and Wildlife Service, October 2018).

The reasons for this decline appears to be layered and include: changing demographics, subcultures related to hunting, and shifting perceptions of hunting and firearms among other factors. National demographics are changing while the demographic profiles of hunters have remained constant. Since the US Fish and Wildlife Service started tracking demographics of hunters and anglers in 1955, their data has reflected that participants have overwhelmingly been white men. According to the 2016 National Survey of Fishing, Hunting, and Wildlife-Associated Recreation, 97 percent of hunters were white and 90 percent were men. Conversely, the same 2016 National Survey reflected that just 10 percent of hunters were women, while 3 percent were Hispanic, and the sample size of Asian and African American hunters was too small to be accurately estimated. In contrast, these demographic groups represent a greater, if still underrepresented, proportion of participants in related outdoor activities like fishing and wildlife watching.

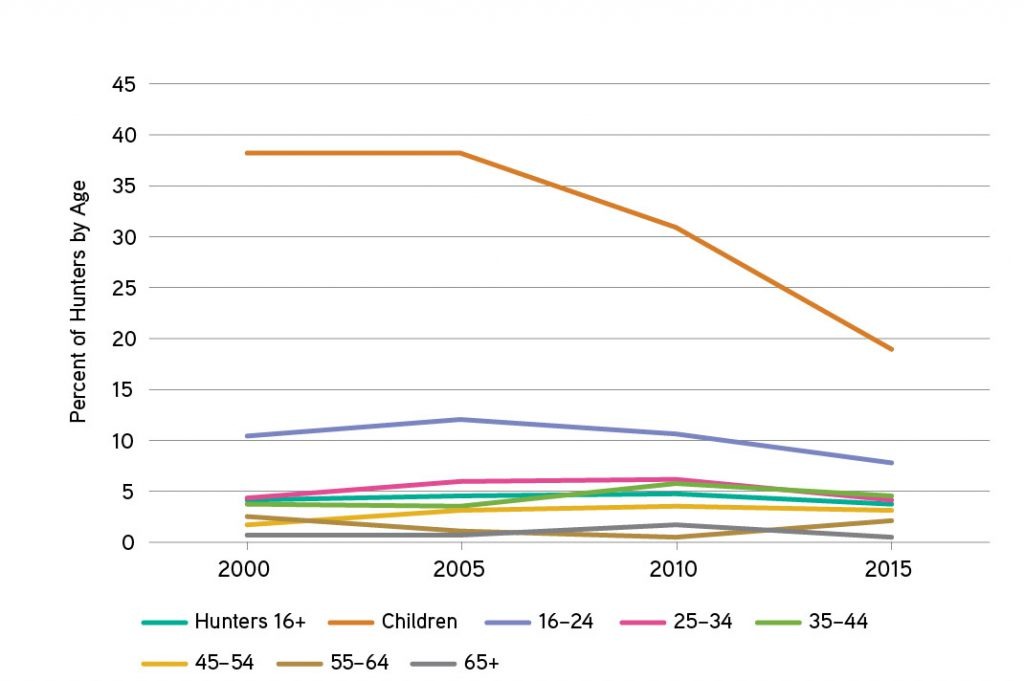

Hunting Recruitment Rates by Age: 2000, 2005, 2010, and 2015 (Population 6 Years of Age and Older)

SOURCE: Recruitment and Retention of Hunters and Anglers: 2000-2015 (Washington: US Fish and Wildlife Service, April 2019).

NOTE: Recruitment rates are calculated as the percent who have participated in the Survey year who were first time participants.

Long-Term Trends in New York State Hunting Participation & Related Funding

In New York, the state’s Conservation Fund is supported through the sales of hunting, trapping, and fishing licenses as well as associated penalties. These funds (through legislative appropriation) are used by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation according to state law for “the care, management, protection and enlargement of the fish, game and shell fish resources of the state and for the promotion of public fishing and shooting.”

An annual hunting license is required for hunters that are twelve years old and older using a firearm or bow to take wild game. Those under 12 are not allowed to hunt. A hunter education certificate is required for all new hunters prior to purchasing an annual, or utilizing a lifetime, hunting license, which allow for the hunting of big and small game. There are a number of different types of hunting licenses, privileges, permits, stamps, or tags that can be held in addition to the annual hunting license, but an annual or lifetime hunting license is required as a precursor to obtaining those.

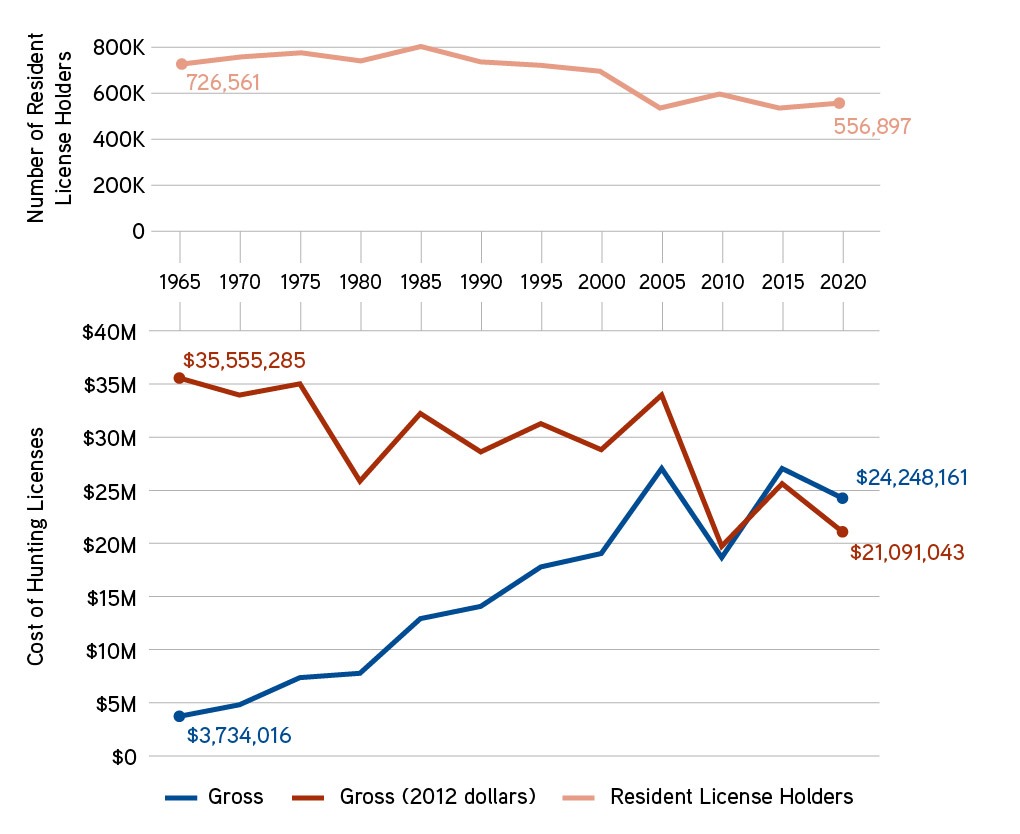

Mirroring national trends, the number of people participating in hunting in New York has generally declined over the last several decades. The number of resident license holders fell from 726,561 in 1965, and a high of 803,112 in 1985, to 556,897 in 2020. This represents a 23.4 percent decrease overall, and a 30.7 percent decrease since the mid-1980s. For 2019-20, US Fish and Wildlife Service data reflects that the gross cost of hunting licenses sold in New York was $24,248,161. Adjusted to 2012 dollars, this represent a decrease of 40.7 percent since 1965 (see chart below).

Hunting License Sales and Adjusted Costs in New York State (US Fish and Wildlife Service Hunting License Data)

SOURCE: US Fish and Wildlife Service Hunting License Data (Washington: US Fish and Wildlife Service, 2020).

Hunting Education and The COVID-19 Hunting Season

New York State launched the first required hunter education program in the country in 1949. Most states now require some form of hunter education course for at least some groups of hunters. Since the state started collecting information on hunting related shooting incidents rates in the 1960s, both the number and the rate of incidents has significantly declined. In the 1960’s the average number of incidents per year was 137; in the 2010’s it was 21—a nearly 85 percent decrease (far outpacing the decline in hunting participation). Over the last decade the number of incidents has also continued to consistently decrease. In 2019, there were 12 incidents, including one fatality.[3] In the context of increased hunter education course enrollment and license purchases in 2020, DEC Commissioner Basil Seggos recently emphasized that:

We want 2020 to be the safest hunting season on record and to make sure all hunters, whether they have decades of experience or are just starting out, follow the principles of hunter safety […] follow the tenets taught in DEC’s Hunter Education Course, and put safety first in every hunting trip this season.

Many states previously provided the option of completing significant portions of their hunter education course online, while generally requiring an in-person field day. In recent years, however, some states have provided a fully online option. In response to COVID-19, several more states across the country shifted their course offerings further and completely online. These included: California, Idaho, Wisconsin, and Kentucky. The New York DEC announced in April of 2020 that the course certification could be completed entirely online through the hunter-ed portal (since September, in-person options have also resumed). To further increase access the deadline for enrolling in the course was extended from June 30th to August 31st, and thereafter extended to December 31st. In July, an additional bowhunter education course, required for hunters who use a bow and arrow to hunt deer or bear, was also offered online. The Department also revamped the online Automated Licensing System this July to sell licenses and privileges to those with hunting education certification.

As of October 29th, 103,143 people had registered for the New York State online hunter education course and 56,603 people had completed the course. This represents a dramatic increase over a typical year in which approximately 20,000 people complete the course. Over half (56 percent) of those who completed the online course were 30 years-old or younger; this is important as the percent of younger hunters has been declining in New York in recent decades. In addition, 35 percent of those individuals that completed the course were women. While women are the fastest growing demographic cohort in hunting, nationally they only account for 10 percent of hunters. State level hunting statistics have not previously included demographic data on race and ethnicity, but that is also changing as optional questions have been added to the new online systems.

Ages of Those Completing Online Hunter Education Course, 2020

| Age Range | Percent |

| 11-20 | 32% |

| 21-30 | 24% |

| 31-40 | 22% |

| 41-50 | 12% |

| 51-60 | 7% |

| 61-70 | 3% |

| 71+ | <1% |

When the DEC opened annual hunting licenses for sale on August 10th for the 2020-21 season (September 1, 2020-August 31, 2021), it was reported that the Department experienced record purchases. On the first day of sales the department sold $922,444 in licenses. This represented an almost threefold increase over the first day of 2019 revenues of $347,103. Sales opened ten days later this year than in 2019, however, so those numbers may reflect an initial rush, rather than a sustained and substantial increase. The sales in August 2020 represented a 15 percent increase from the previous year—with $8,899,417 (August 10 – August 31) of license sales in 2020, over $7,735,643 (August 1 – August 31) in 2019. If sales continue in this direction, they may represent a reversal in long-term hunting participation trends in New York and in the United States more broadly. That reversal, while promising, is not yet assured and, as researchers at Cornell University have suggested, it depends in part on the dynamic social structures that new hunters must navigate, engage with, and help create. In turn, it depends on how public policy, agencies, and organizations can collectively continue to support new hunters as they traverse those dynamics so that they want to stay engaged.

Conclusions

The jump in certification course completions and initial spike in hunting license sales this year in New York likely reflects a significant number of first-time hunters, along with some returning hunters, suggesting a break from downward trends in hunting participation in the state and across the country. At present, it is unclear the degree to which this increase is due to changes related to COVID-19 and a shift towards outdoor recreation more broadly or the improved access to the online hunting certification process in New York. Past research has found that states with required hunter education programs as a whole do not have lower participation than states without these programmatic requirements.[4] That research, however, does not necessarily apply to the impact of changes to a particular state-level program or reflect the unprecedented present circumstances.

Thus far, it appears that at least some other states, including Michigan, Pennsylvania and Tennessee, are also experiencing an uptick in hunting participation this year. Understanding these trends has important implications not only for hunter education and outdoor recreation, but for conservation, restoration, and wildlife management programs in New York and across the country. More time and research is needed, however, to better understand what factors are most driving these emerging trends in and across states, whether or not new hunters—particularly young people, women, and people of color—will stay engaged in hunting, how policies and programs can better support them in doing so, and what impacts will occur as a result. As that happens, researchers at the Rockefeller Institute will continue to keep you updated.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Laura Rabinow is deputy director of research at the Rockefeller Institute of Government.

[1] Each state gets between .5 percent and 5 percent of the total funding based on a formula.

[2] The Federal Aid in Sport Fish Restoration Act, or Dingell-Johnson Act (1950), is a complimentary law related to funding fish habitat restoration and conservation

[3] According to the DEC of those 2019 incidents: “5 incidents were self-inflicted and 7 were two-party firearm incidents. Of the two-party firearm incidents, 2 of those victims were not participating in any type of hunting activity and were passerby’s in vehicles. The remaining 4 victims were not wearing hunter orange while hunting with others. Wearing hunter orange while afield and ensuring it is visible decreases your risk of being injured while hunting.”

[4] Heberlein, Thomas A., and Elizabeth Thomson. “Changes in US hunting participation, 1980–90.” (1996): 85-86.