Q: What are some of the approaches colleges and universities are taking to integrate work and life experiences in learning?

A: We can break down the different approaches into three different categories. There’s applied learning, which is best summed up as “learning by doing,” or practice-based activity, like an internship. There’s the assessment of prior learning, where colleges and universities look at one’s college and work experiences and determine what program requirements are satisfied by what has been learned already and what still needs to be learned for a degree. Finally, there are micro-credentials, compact credentials that can incorporate both applied learning and prior learning assessment, and can stack together to an initial or advanced degree.

These three approaches each have distinct advantages, and require some research on the part of the learner about which might best fit their particular situation and goals.

Let’s run down the list. What is applied learning?

Applied learning is not new in higher education — internships, for example have been around for quite a while. The State University of New York (SUNY), for example, groups applied learning into three broad categories: work-based, discovery, and service-based.

The work-based learning model includes internships, in which a student has a professional role within an organization and is expected to carry out tasks appropriate to the role. It’s a job. In part, a key aim of the internship is to give the student work experience in a relevant professional setting.

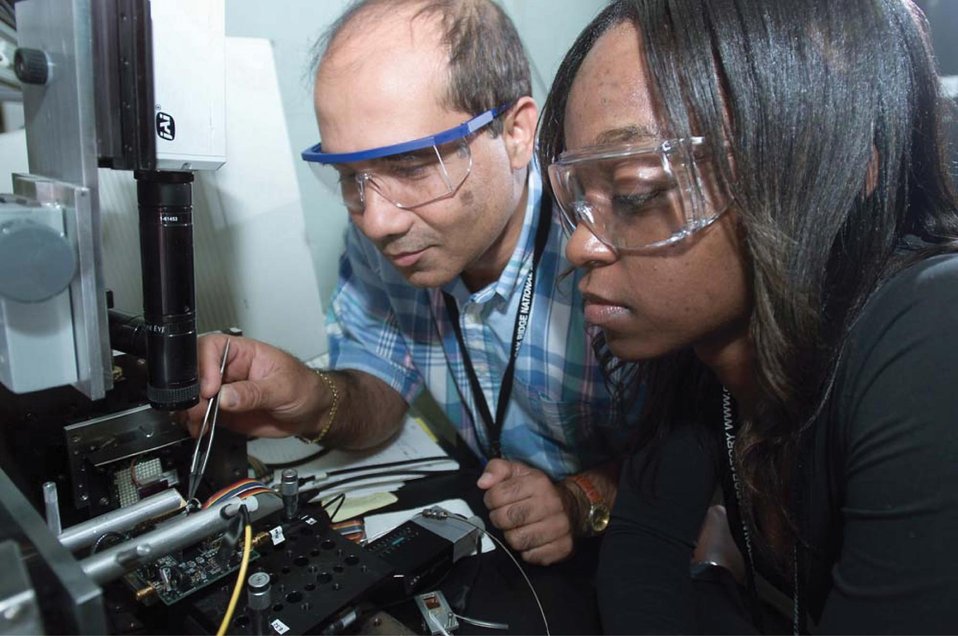

Discovery learning is participation and engagement in field studies, study abroad, or a research project. Research projects can include, for example, working with a professor or a research team in a lab or lab-type setting. Students acquire specific skills through the experience, often while applying knowledge learned in courses.

The third category of applied learning is service-based, in which students work with a community group or nonprofit organization. It’s similar to the work-based approach, but instead focuses more on community service and the personal and social learning that comes from volunteerism. Volunteering at a homeless shelter or working on community days are examples of service-based learning. Students are engaging with different people in different settings, and applied learning here is largely about what students take away from those experiences.

Common to every one of these approaches is that students are engaged in practical, applied experiences. Ultimately, the broader interest of the applied learning model is to connect work and learning more directly and explicitly.

What are some of the benefits of the applied learning approach?

Applied learning is another avenue, another way for students to learn. Students are engaged with the work, and so not only acquire skills for application but also often gain deeper understandings of their fields. Applied learning, especially work-based experiences, also helps students to prepare for — and especially for work-based experiences, to connect to — the workforce.

And the challenges?

Students may have limited opportunities for applied learning experiences. Considering internships, for example, about half of college seniors report having one or more applied work-based learning experiences over the course of their studies. Others may not have opted to take up internships, in part because the opportunities available to them offer little or no pay. Some fields, especially professional fields of study such as business, tend to offer more and more relevant internship opportunities than is the case in, say, the arts and humanities.

Are there ways we can address the access issue?

New thinking might lead to increasing the opportunities available to students. Returning to the internship example, we already know that upwards of 75 percent of students enrolled in four-year colleges and universities work during their undergraduate career, whether that is at a full-time, part-time, or summer job. So the question really is, how do we connect that experience to what is being learned in coursework? How do we encourage current employers of students to engage with colleges and faculty, to better connect work experiences to learning?

We already know that upwards of 75 percent of students work during their undergraduate career, whether that is at a full-time, part-time, or summer job. So the question really is, how do we connect that experience to what is being learned in coursework?

Working under existing campus arrangements that assure meaningful applied learning experiences, current employers of students might be encouraged to support structured internship experiences of their student employees if demands are modest and the engagements are facilitated and supported. Chambers of Commerce might also help to further establish and strengthen learning opportunities for those working in member establishments, especially in small and medium-sized enterprises. Work-based learning opportunities within a scheduled term-time course is another way to offer applied learning for students who cannot take up full internships.

What is assessment of prior learning?

This is another way learning is connected to work, taking into account that individuals acquire knowledge and skills over time in a variety of ways. Instead of requiring students to complete all coursework in a degree program, colleges and universities can assess what individuals know and are able to do, and credit the acquired knowledge and skills toward the degree.

What are some examples?

It is worth mentioning that colleges and universities have, for some time, recognized coursework taken at other campuses. A fairly common example is the community college transfer. Students go to a community college for two years, then transfer to a four-year college or university with advanced standing for the coursework they took. In part, owing to careful elaboration of coursework generally accepted toward a four-year degree, transfers from community colleges into four-year colleges now happen relatively smoothly in many states. However, each college undertakes an evaluation of the prior coursework, especially for credit toward a bachelor’s degree in particular fields. For example, a transfer student pursuing a four-year degree in the sciences may not have completed the advanced calculus course needed for upper-division coursework in the field. Students need to be informed about specific transfer policies at the colleges and universities of interest. A new, seamless transfer policy within SUNY guarantees students with a junior standing admission to a SUNY four-year campus if the student completes the specified transfer path in the associate’s degree.

Another example is credit awarded for performance on standardized examinations for particular subjects and courses. The College-Level Examination Program (CLEP) is a widely recognized option. The challenge here is that campuses and programs differ on whether college-level examinations can be used for credit toward a bachelor’s degree, and what levels of performance are needed to obtain credit.

Some organizations also assess learning that takes place outside of traditional higher education. The Council for Adult and Experiential Learning (CAEL) has long undertaken such work on behalf of employers as well as higher education institutions. Within SUNY, Empire State College evaluates job training and military service for credit for its own students and in support of such assessments on other SUNY campuses. At Empire State, an applicant’s portfolio of prior courses and work experience is assessed with respect to knowledge and competences acquired. Credit for prior learning is applied and additional courses are identified that will meet the requirements for the student’s intended bachelor’s degree. It’s an individualized process, and is quite well-suited for working professionals. Empire State offers courses catering to the individual student around not only prior experience, but also schedules.

What about micro-credentialing? It sounds like a way for people to attain specific skills for specific purposes.

Micro-credentialing is a way to recognize a set of learned competencies or skills. Micro-credentials can be recognized with a digital badge, an electronic icon that links to a list of what was mastered, assessments, and even examples of student work. They are different from two-year, four-year, and postgraduate degrees in that they are not degrees, but rather recognition that students have successfully completed training in a particular area. Individual micro-credentials can help to upskill a current worker and/or be customized to meet specific employer needs.

A good example is certain software skills. Students can take classes or workshops that teach and develop skills to work with XYZ software products. Upon completion, students are awarded the micro-credential and earn a digital badge, which they can then list on their resume and highlight for employers that they have developed those specific software skills.

Micro-credentials obtained through colleges and universities are generally comprised of courses from existing degree programs and can be bundled with an applied learning experience and/or recognize workplace learning as part of the total credits allocated. Multiple micro-credentials often can be stacked together to allow the recipient to earn an initial or advanced degree.

We are also seeing growth in short-term certificate programs, as another alternative to a full degree. In New York State, credit-bearing certificates are registered by the state. For example, my academic department at the University at Albany has a certificate program in International Education Management for professionals and aspiring professionals who work with higher education activities that span country borders. This specialty field responds to the recognition that work with international students, faculty, and programs often involves distinct challenges. Requirements for visas, finance, and work permits are specific to this field. Students pursue a three-course program that focuses on specific aspects of international education management, higher education finance, and administration within higher education, to obtain a certificate. In short, students learn essential knowledge to take up work responsibilities in the field.

What are the benefits and uncertainties of micro-credentialing?

Micro-credentialing is a faster, often cheaper, way to attain and recognize specific skills that are needed by individuals or a company.

However, there are many different micro-credentials, and the range introduces some lack of clarity on what training people are receiving and what they are learning. In the workplace, people attending a daylong workshop may obtain micro-credentials for that training, say certain software skills. Alternatively, there are other software training programs with multiple classes that extend over several months. Both may lead to micro-credentials in software skills, but they will differ in content, requirements, and the depth of what is learned. This variation makes it difficult to interpret and use the badges, and also for employers to understand the substance and quality of the training and what individuals have learned. Information on which to judge the quality of, and learning under, micro-credentials may be available from providers or a range of third-party entities.

While micro-credentials awarded by colleges and universities are not the same as academic degrees or certificates, they do offer some assurance of quality under established faculty review processes. In SUNY, for example, campus-level processes for the development and review of micro-credentials operate under a system-wide framework.

Overall, is there a best approach to integrate learning and work in higher education?

Better put, a range of approaches can serve to integrate work and learning, to better prepare graduates for work and adults for advancing in careers. Different approaches serve different students, from the typical undergraduate anticipating entry into work following graduation, to the mid-career professional seeking to assume new responsibilities, to displaced workers looking to develop new skills and knowledge for available jobs. The whole point of these different approaches is to give particular students a range of options to connect learning and work.

Revised from an earlier version for clarity and content.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Alexander Morse is a policy analyst at the Rockefeller Institute of Government

Trevor Craft is a research assistant at the Rockefeller Institute of Government