The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Rockefeller Institute of Government.

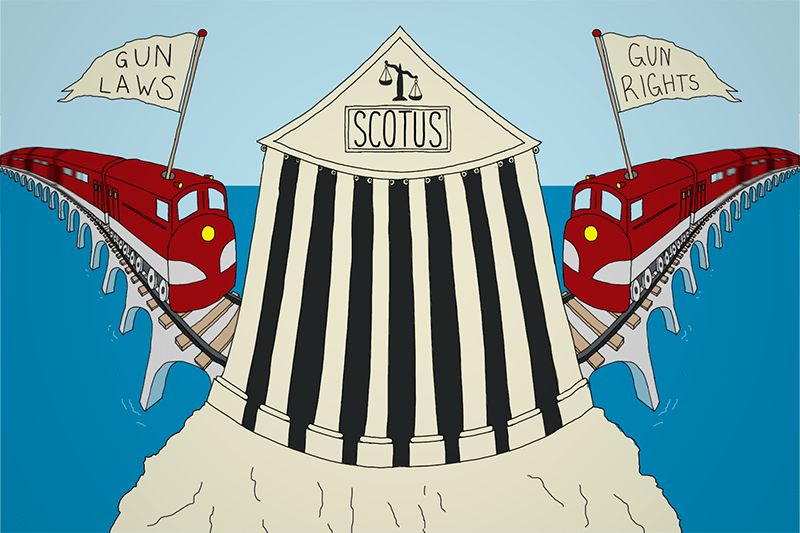

Like two trains hurtling toward each other on the same track, national gun policy is facing an impending collision of two opposing forces. On the one hand, the recent spate of gun violence, including an alarming number of mass shootings, has again heightened attention on the nation’s inadequate gun laws, and strengthened calls for changes strongly supported by the public, as well as by most gun owners. On the other hand, the nation’s federal courts have been staffed by a large number of conservative judges, many appointed by President Trump, including his three appointees to the Supreme Court. Among the issues uniting these justices is adherence to a singularly expansive view of gun rights, far exceeding that set out by the Court in its 2008 DC v. Heller decision. These conservative jurists are poised not just to thwart, but throw into gear-grinding reverse, the nation’s gun control laws.

That collision is now in motion, thanks to the Supreme Court’s recent decision to hear an appeal to a ruling upholding New York State’s “may issue” concealed carry gun law.

The Move to Advance Gun Safety

President Biden campaigned on a broad gun safety agenda and was spurred by recent events to decry gun violence in unequivocal terms: “Gun violence in this country is an epidemic, and it’s an international embarrassment.” Biden went on to propose a series of actions, including several executive orders. Chief among them, he charged the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives (ATF) to restrict ghost guns, a reference to legally obtainable gun parts that can be easily assembled, but that do not include serial numbers, making them untraceable. The threat from these weapons is not merely hypothetical. According to the ATF, 10,000 ghost guns were retrieved from crime scenes in 2019. Since then, authorities around the country have reported dramatic increases in criminal use of the untraceable weapons. One need hardly ask the obvious question: why would any law-abiding person want or need a gun that is untraceable?

In addition, Biden has directed that a new, comprehensive study of gun trafficking be commissioned—the first of its kind since 2000—and the drafting of a model “red flag” law. Also called Extreme Risk Protection Orders, these laws, adopted by 20 states, allow authorities to remove guns from individuals who pose an imminent threat to themselves or others, subject to a judicial hearing. The goal of the model law is to encourage more states to adopt this measure, which has demonstrably beneficial effects, especially in warding off suicides. A federal version of the law sits in Congress.

“Gun violence in this country is an epidemic, and it’s an international embarrassment.”

— President Joe Biden

He also called for the regulation of “stabilizing braces,” simple devices that can be attached to pistols that are “intended to increase the accuracy of AR-15-style pistols and allow users to fire them much like their rifle counterparts.” Late last year, the ATF moved to regulate these devices, which would have subjected them to greater regulation (existing law tightly regulates short-barreled guns, which is what the braces make them), but outcry from the gun community prompted the ATF to abandon the effort. Ironically, two recent mass shooters used these very weapons, including the Boulder, Colorado shooter who killed 10 people in March and was armed with a Ruger AR-556 pistol.

Biden called for funneling more funds to community violence intervention programs, targeted efforts stymied by last year’s pandemic, that have demonstrated success in reducing violence in targeted areas. He also called on Congress to repeal a 2005 law giving the gun industry unique legal immunity from lawsuits.

Finally, Biden has nominated David Chipman to be the new director of the ATF, a significant move for three reasons: Chipman is a former ATF agent who therefore knows the agency and is also affiliated with a gun safety organization; the agency has been without a permanent director for 13 of the last 15 years; that, in turn, is because gun rights advocates have deployed every effort to keep the agency administratively weak by thwarting the appointment of permanent leadership.

Separately and together, these are significant unilateral actions. In addition, Congress has key items before it. The House of Representatives has approved bills to establish uniform background checks for all gun purchases (roughly 20 percent occur without a check), to extend the background check time from three to 10 days, and to renew the Violence Against Women Act. All sit now with the Senate. Given the Senate’s 50-50 split (with Vice President Harris the tie-breaking vote) and the existence of the filibuster, the fate of these and most other Democratic bills are in limbo. This means one of three possibilities: that a bipartisan compromise will eventually be reached on at least some major legislation, perhaps including the gun bills; that the filibuster will be eliminated, allowing legislation to be approved by simple majority; or that the filibuster will stand, and nothing will pass. Each of these options seems equally likely at the moment.

Filibuster aside, this political momentum is symptomatic of where most of the nation stands on the gun issue. As the students who railed against government inaction in the aftermath of the Parkland High School shooting in early 2018 said, the time for “thoughts and prayers” instead of action is over. One student wrote, “Do something instead of sending prayers. Prayers won’t fix this. But gun control will prevent it from happening again.”

The Move to Expand the Second Amendment

Arrayed against this political momentum is a different, contrary force—one that has received relatively little attention. Yet, it is a force primed to not only halt but reverse the nation’s limited progress on greater gun safety.

Since the early 1980s, a concerted legal movement, spearheaded by the Federalist Society, has been constructed and mobilized to cultivate a generation of conservative legal thinkers and practitioners. Their chief goal has been to push the nation’s courts to the right. This effort has met with great success, especially in realizing the appointment of judges who share an extremely high degree of conservative ideological coherence. Chief among these values is a nearly unwavering adherence to an expansive definition of gun rights. Further, these judicial appointees tend to be relatively young, all but guaranteeing enduring influence on court doctrine for decades to come.

Trump appointed 30 percent of all active federal appeals court judicial positions, 27 percent of active district court judges, and three Supreme Court justices.

To appreciate the influence of the Federalist Society, consider this: during George H.W. Bush’s four-year presidency, nine of the 42 federal appeals court judges he appointed were members of the Federalist Society. During George W. Bush’s first term as president, more than two-thirds of his appeals court nominees were connected to the Federalist Society. In his two terms, a majority of his federal courts of appeal appointees were members, as were his two Supreme Court nominees. In his four-year presidency, Donald Trump appointed 54 judges to the 13 federal appeals courts. Nearly all of them are Federalist Society affiliated. In total, Trump appointed 234 federal judges. Thanks to the elimination of procedural barriers to court appointments—a focus of Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell (KY)—President Trump’s impact was disproportionately large.

Indeed, McConnell achieved his promise for the Trump presidency to “leave no [judicial] vacancy behind,” meaning that Trump’s administration was the first in decades to fill every unfilled seat by the end of the administration. In all, Trump appointed 30 percent of all active federal appeals court judicial positions, 27 percent of active district court judges, and three Supreme Court justices.

None of this is to suggest that presidents do not have a right to appoint judges that share their ideological predilections. Far from it. But the systematic press to push the courts to the far right is unlike anything our judicial system has ever witnessed.

Several studies confirm the unique impact of these Federalist Society-sponsored judges on court rulings. For example, a sweeping study of the ideological leanings of Trump-appointed judges, based on a comparative examination of 117,000 opinions issued by over 2,400 judges spanning 14 presidents from 1932-2020, concluded that “Trump has appointed judges who exhibit a distinct decision-making pattern that is, on the whole, significantly more conservative than previous presidents. . . .his judges are more to the right than those of any recent Republican president.” A different study of 950 en banc federal court decisions (those made by all active members of the respective courts of appeal when they sit together to render decisions for the circuit) spanning 54 years through 2020 found “a dramatic and strongly statistically significant spike in both partisan splits and partisan reversals” in the second half of Trump’s term, 2018-20. No such pattern was observed in any prior period of the study. The authors referred to this “surprising” deviation from the prior relatively nonpartisan era as “weaponizing en banc.”

Capping the federal court system is the Supreme Court, where six current members are Federalist Society-connected. Among the justices, five have judicial records on the Second Amendment that are far more conservative than the Court’s 2008 Heller decision, which established a personal right to own a handgun for defense at home.

US Supreme Court Cases on Gun Control from 1886 to Present

| Case | Matter | Ruling | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|

| Presser v. Illinois, 116 U.S. 252 (1886) | Herman Presser, as part of a citizen militia, marched through Chicago with other armed men. He was charged with parading and drilling an unauthorized, armed group that was unaffiliated with state and federal militia. | States may forbid private armies. The Second Amendment serves only as a restraint upon the federal government and not the states. | Unanimous |

| United States v. Miller, 307 U.S. 174 (1939) | Jack Miller and Frank Layton were charged with transporting an unregistered sawed-off shotgun—an illegal weapon under the National Firearms Act—from Oklahoma to Arkansas. | The National Firearms Act’s regulation of named gangster-type weapons using the taxation power in interstate commerce of such weapons was valid and did not violate the Second Amendment, which “must be interpreted and applied” to the “obvious purpose to assure the continuation” of militia forces. | Unanimous among 8 justices (the 9th abstained) |

| District of Columbia v. Heller, 554 U.S. 570 (2008) | Six DC residents challenged the constitutionality of the Firearms Control Regulations Act of 1975, a local DC law that restricted residents from owning handguns. Dick Anthony Heller, one of the six, was a special police officer who could carry his gun for work, but could not have one in his home. | The Second Amendment protects the individual right to possess a firearm for lawful purposes, like self-defense in the home, but that right is not unlimited. The District of Columbia handgun ban violated the Second Amendment. | 5-4 |

| McDonald v. City of Chicago, 561 U.S. 742 (2010) | Otis McDonald and three other Chicago citizens filed suit against the city’s handgun ban that precluded them from owning handguns. | The individual right to keep and bear arms, recognized in District of Columbia v. Heller (2008), extends to states. | 5-4 |

| Caetano v. Massachusetts, 577 U.S. ___ (2016) | Jaime Caetano was convicted for possession of a stun gun that she obtained to defend against an abusive boyfriend. Massachusetts state law prohibited such possession. | The Second Amendment extends to all “bearable arms, even those not in existence at the time of the founding.” | Unanimous |

| New York State Rifle & Pistol Association Inc. v. Corlett | Two men challenged a New York State law that rejected their applications for concealed-carry firearm permits. This case could affect the constitutionality of firearms carrying outside the home. | The appeal challenging the NY pistol permit law has been accepted by the Supreme Court. Oral argument is scheduled for October. This ruling could alter the scope of Heller (2008). | TBD |

Leading this group is Justice Clarence Thomas, who in a series of increasingly strident post-Heller dissents, bemoaned what he has labeled the Courts’ “treatment of the Second Amendment as a disfavored right,” calling it “cavalier,” and a “constitutional orphan.” Justice Samuel Alito has shared Thomas’ dismay, charging that the Court has treated the right to bear arms as “a second-class right.” Both Justices Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh have concurred with Thomas’ Second Amendment dissents. Before joining the Supreme Court, Kavanaugh and Justice Amy Coney Barrett both authored dissents in federal court decisions extolling a broader view of Second Amendment rights consonant with that of Thomas.

Nothing in post-2008 Second Amendment case law warrants these outlandish labels and judicial handwringing, which seem designed mostly to provide a rallying cry for Second Amendment absolutists. On the contrary, conservatives lose sight of the fact that they won a major victory in the Heller case, especially since the Second Amendment was drafted, debated, and interpreted for two centuries as a right pertaining only to citizen service in a government organized and regulated militia, not as a personal right. Beyond that, Heller managed to balance this new right by noting, essentially, that most existing gun laws would probably be permissible under their rubric and that is largely what the lower courts have concluded.

Based on the writings and dissents of Thomas and his allies, it is more likely than not that they would sweep aside gun regulations that, up until now, have withstood court challenges, including state assault weapons bans, restrictions on large capacity ammunition magazines, and restrictions on public gun carrying. Instead, they would—and, I believe, eventually will—declare a constitutional right to publicly carry firearms. Such a decision would be at odds with our gun law history, public policy, public safety, and the common sense of the public. (Ironically, laws restricting gun carrying were nearly universal among the states by the end of the nineteenth century.)

Former Supreme Court reporter Linda Greenhouse speculated that the current Court might be reluctant to act on their gun rights predilections right now because of the current spate of shootings and the turmoil that has ensued. Yet that possible reluctance has apparently been cast aside with the high Court’s decision to hear a challenge to New York’s longstanding pistol permit law in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Corlett.

Current New York law restricts the concealed carrying of firearms outside the home to individuals who demonstrate “proper cause.” Seven other states plus the District of Columbia have such “may issue” laws, while 23 states have “shall issue” carry laws, meaning that the states must issue permits unless applicants fall into a prohibited category, such as convicted felons, those adjudicated to be mentally incompetent, and those dishonorably discharged from the military. The remaining 19 states have eliminated permitting entirely (40 years ago, only one state, Vermont, did not require a permit, and 19 states did not allow civilians to carry concealed weapons).

The question that the Supreme Court intends to resolve is, “whether the Second Amendment allows the government to prohibit ordinary law-abiding citizens from carrying handguns outside the home for self-defense.” If the Supreme Court rules that this law is unconstitutional, the permitting of firearms under existing laws and policies is in immediate jeopardy. Further, the Court’s decision may also create a new standard to challenge a myriad of gun control measures.

Existing permit-based carry state laws would be directly impacted by this decision, meaning those states would likely join the other 19 states that do not require a state-issued permit. At this time, there is no federal law specifically addressing concealed carry. However, other federal laws, like the Gun-Free School Zones Act, limit where individuals may knowingly possess firearms could also be at stake. Federal law also restricts firearms in federal facilities, post offices, and airports. Depending on the scope of the decision, armed individuals may be able to carry in these sensitive locations.

Moreover, if the Court decision creates a new standard that the Second Amendment affords protections to individuals to possess firearms outside the home, the legal equilibrium that has existed since the District of Columbia v. Heller case will be disrupted. This could invite new and renewed legal challenges to all types of gun control laws and policies, including restrictions on the availability and accessibility of firearms (e.g., assault weapon bans, interstate sale prohibitions) to the person-specific prohibitions on who may purchase or possess firearms.

Whether the conservative majority rules narrowly or broadly in this case (oral argument is set for this October), I believe this to be the first step by these justices to realize their ultimate vision of the Second Amendment: that gun rights exist whenever a human hand comes in contact with a firearm—or even firearm accessory. On the day that vision comes to pass, should it come, the country will witness a political collision of the first magnitude.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Robert J. Spitzer is distinguished service professor of political science at SUNY Cortland. He is the author of five books on gun policy, including Guns Across America: Reconciling Gun Rules and Rights (2015) and The Politics of Gun Control (8th ed. 2021). He is also a member of the Regional Gun Violence Research Consortium.