January 25, 2018

This policy brief examines the growing separation between the federal government and the states when it comes to marijuana policy and the federalism implications of this divide. Since the 2016 election, the states and the federal government have been on a collision course over the implementation of state marijuana policy and the enforcement of federal law. The essays collected in this brief highlight some of the major issues currently at play in United States marijuana policy and potential issues to watch in the coming year.

Until the early twentieth century, marijuana was used in the United States in a variety of ways and was mostly unregulated. Early colonists were encouraged by Britain to grow hemp and the crop was used in the production of rope, paper, and cloth. Marijuana was also an ingredient in mainstream medicines as a treatment for a variety of ailments, including cholera, dysentery, alcoholism, opiate addiction, epilepsy, and asthma. The recreational smoking of marijuana was also introduced.

The first regulation of marijuana occurred with the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act, which required that over-the-counter drugs containing cannabis had to be labeled. As marijuana use was tied to the 1910 influx of Mexican immigrants to the US, twenty-nine states passed marijuana prohibitions. In 1937, Congress passed the Marihuana Tax Act to “impose an occupational excise tax upon certain dealers in marihuana, to pose a transfer tax upon certain dealings in marihuana, and to safeguard the revenue therefrom by registry and recording.” The act did not criminalize the drug per se, but failure to pay said taxes or follow regulations was punishable by fines up to $2,000, up to five years in jail, or both. The Marihuana Tax Act stayed on the books until 1969 when the Supreme Court struck it down as a violation of the Fifth Amendment protection against self-incrimination in Leary v. United States.

After the Marihuana Tax Act was deemed unconstitutional, the Nixon administration encouraged Congress to create a new system for classifying drugs based on their medical utility and addictive potential. The result was the 1970 Controlled Substances Act, which established federal drug policy. Marijuana — like heroin and LSD — was classified as Schedule I, meaning it has no currently accepted medical use and has a high potential for abuse. With this classification, marijuana became illegal under federal law.

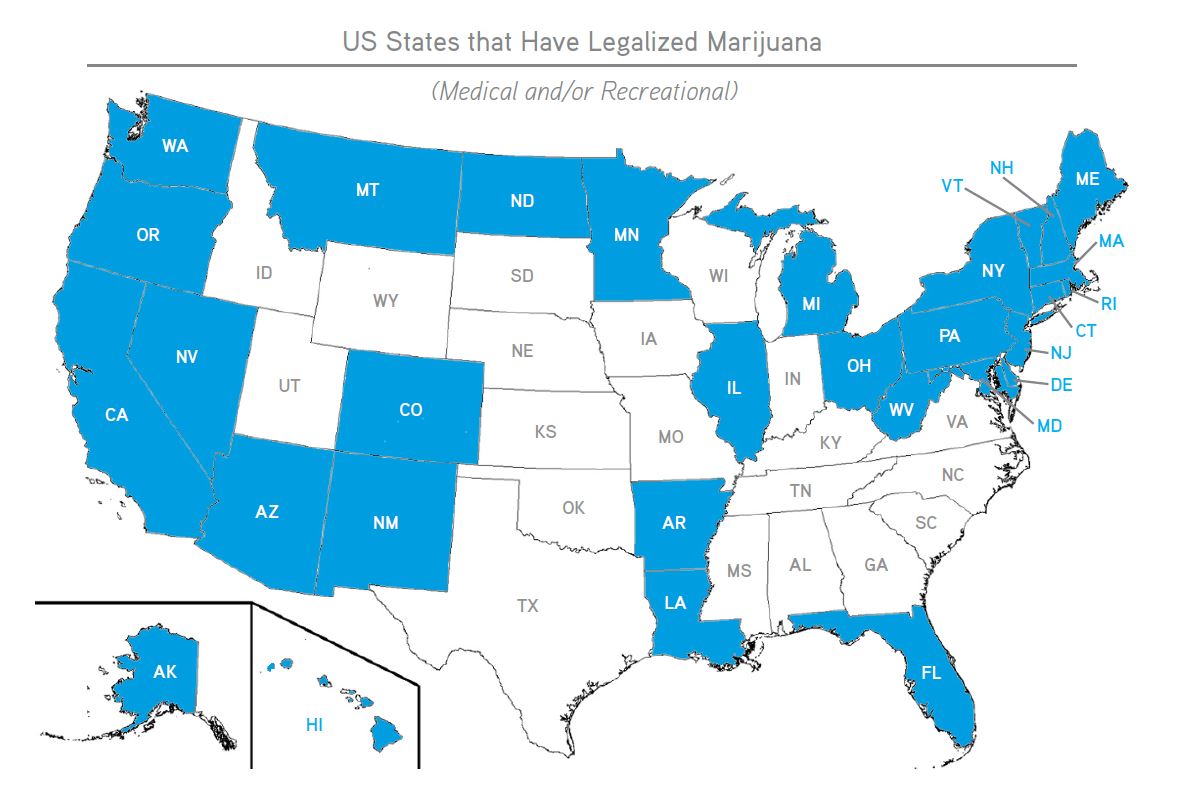

In 1996, California became the first state to enact medical marijuana legislation with the Compassionate Use Act. In the next four years, Oregon, Alaska, Washington, Maine, Hawaii, Nevada, and Colorado followed suit. Colorado became the first state to legalize recreational marijuana in 2014. By the end of 2017, eight states and the District of Columbia had passed legislation permitting recreational marijuana and twenty-nine states and the District of Columbia have medical marijuana laws on the books.

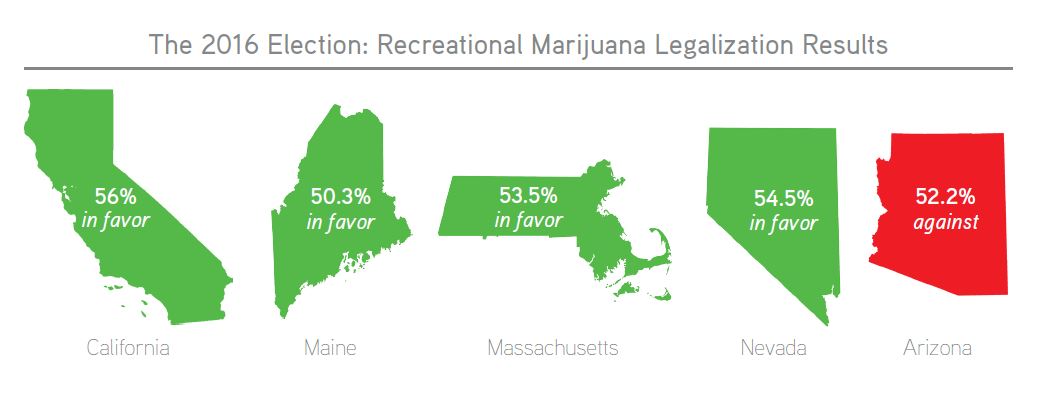

The 2016 election was memorable for many reasons, but lost in the shadow of the presidential outcome was the big night marijuana legislation had in the states. Three states (Arkansas, Florida, and North Dakota) passed initiatives legalizing medicinal marijuana, marking the first time that more than half of the states have permitted the use of medicinal marijuana. Voters in Montana rolled back some restrictions on their existing medical marijuana law. Meanwhile, California, Maine, Massachusetts, and Nevada all passed legislation to allow for recreational marijuana use. The only loss for marijuana at the voting booth in 2016 was in Arizona, where voters rejected Proposition 205, which would have legalized recreational use of marijuana by adults twenty-one and older (medicinal marijuana laws passed in Arizona in 2010). In the aftermath of the election, the entire West Coast now permits some type of marijuana use and recreational use gained a foothold in the Northeast. One in five people in the United States now live in a state where marijuana is legal.

While this could be seen as a victory for proponents of such measures, it may be setting states up for a showdown with the federal government.

Although the majority of states have relaxed regulations of marijuana use and public support for marijuana legalization is at an all-time high, the federal government classifies marijuana as a Schedule I substance under the Controlled Substances Act — the same classification as heroin. Regardless of the legislation of individual states, marijuana is still illegal under federal law. The Obama administration took a mostly hands-off approach to the actual enforcement of federal law; in 2009 then-Deputy Attorney General David Ogden wrote a memo to U.S. attorneys indicating that prosecuting those who are “in clear and unambiguous compliance with existing state laws providing for the medical use of marijuana” were not going to be a priority. After the passage of legislation in Colorado and Washington allowing for recreational marijuana usage in 2012, then-Deputy Attorney General James Cole issued a subsequent memo to U.S. attorneys, reiterating that “in jurisdictions that have enacted laws legalizing marijuana in some form and that have also implemented strong and effective regulatory and enforcement systems,” enforcement of federal law related to marijuana would not be a priority.

But even looking the other way on enforcement of possession in these states, the tension between federal and state law on the legality of marijuana manifests in banking, business, and other federal regulations. Federal banking laws prohibit marijuana dispensaries from conducting money transfers through credit card companies or debit networks, and revenues from marijuana sales cannot be stored in Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) insured banks. Marijuana businesses are also prohibited from deducting business expenses for federal tax purposes. Marijuana’s designation as a Schedule I drug has also impeded running clinical trials to determine potential medical benefits and risks. Members of the Oregon Congressional delegation recently introduced The Path to Marijuana Reform, a package of bills to “pave the way for responsible federal regulation of the legal marijuana industry, and provide certainty for state-legal marijuana businesses which operate in nearly every state in the U.S.”

During the presidential campaign, candidate Trump indicated that marijuana usage was an issue best left to the states, but Trump administration officials have given indications that they intend to rigorously enforce federal laws. In a February 23, 2017, press conference, White House Press Secretary Sean Spicer told reporters:

I do believe that you’ll see greater enforcement of it. Because again, there’s a big difference between the medical use which Congress has, through an appropriations rider in 2014, made very clear what their intent was in terms of how the Department of Justice would handle that issue. That’s very different than the recreational use, which is something the Department of Justice I think will be further looking into.

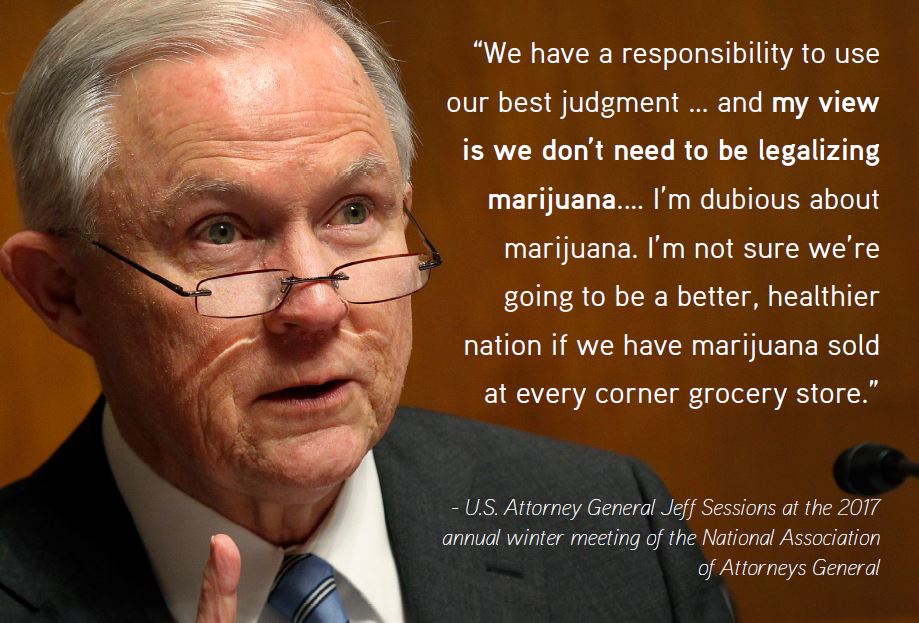

Attorney General Jeff Sessions has been an opponent of marijuana legalization in the past and hinted at a potential Department of Justice [DOJ] crackdown with comments made at the annual winter meeting of the National Association of Attorneys General. “We have a responsibility to use our best judgment … and my view is we don’t need to be legalizing marijuana.… I’m dubious about marijuana. I’m not sure we’re going to be a better, healthier nation if we have marijuana sold at every corner grocery store.”

On April 5, 2017, Sessions sent a memo to U.S. attorneys indicating that he had established a Task Force on Crime Reduction and Public Safety and that one of the charges of the Task Force’s subcommittees is to “undertake a review of existing policies in the areas of charging, sentencing, and marijuana to ensure consistency with the Department’s overall strategy on reducing violent crime and with Administration goals and priorities.”

Resources, rather than rhetoric, may ultimately decide if the Trump administration follows the lead of the 2013 Cole memo or is more aggressive in enforcement. Sessions has recently acknowledged as much; despite his personal dislike for marijuana and skepticism of its benefits, he admitted that the Department of Justice doesn’t have the capacity to come in to a state and do the work of local law enforcement. Marijuana is also big business, which may be persuasive to the current administration. A report by New Frontier Data has found that states with legalized marijuana are on track to generate $559 million from cannabis taxes in 2017. With that much money on the table, it is unlikely that states are going to back down quickly and quietly if the federal government increases enforcement. How this potential showdown over marijuana policy plays out will be illustrative of the current status of the ongoing interplay between federal and state authority and provide potential clues as to federalism under Trump.

Friday, January 19, 2018, was a looming deadline for Congress — unless lawmakers passed some sort of spending plan before midnight, the federal government would shut down. Friday was also a date that proponents of legalized marijuana have circled on their calendars, as that is when the current protections of the Rohrabacher-Blumenauer Amendment would sunset. The amendment prohibits the Department of Justice from using federal funds to interfere with the implementation of state laws that legalize medical marijuana. Earlier versions of the amendment (then known as the Rohrabacher-Farr amendment) have been included in approved budget bills since 2014. While the amendment does not alter the legal status of marijuana at the federal level or cover state laws permitting recreational usage, it did provide some protection for states with medical marijuana legislation from federal intervention. During the federal government shut down, the protections of the Rohrabacher-Blumenauer Amendment lapsed.

The Trump administration, particularly the Department of Justice, has signaled that it intends to more rigorously enforce federal laws regarding marijuana. Attorney General Jeff Sessions personally asked Congress to undo the protection granted by the Rohrabacher-Farr Amendment, stating that it inhibits the Department’s authority to enforce the Controlled Substances Act. In his letter to congressional leadership, Sessions said:

I believe it would be unwise for Congress to restrict the discretion of the Department to fund particular prosecutions, particularly in the midst of an historic drug epidemic and potentially long-term uptick in violent crime. The Department must be in a position to use all laws available to combat the transnational drug organizations and dangerous drug traffickers who threaten American lives.

Without the limitations of the Rohrabacher-Blumenauer Amendment, the Department of Justice would be free to invest its resources in prosecuting dispensaries and medical marijuana users for violations of federal law. Twenty-nine states and the District of Columbia would feel the impact.

States, meanwhile, are not walking away from the continued expansion of legalized marijuana despite the potential uncertainty. For cash-strapped states, the potential taxes and fees generated from legalized marijuana may be too much to give up without a fight; legalized marijuana is estimated to be a $6 billion business that employs 150,000 people and is on track to create more jobs than the manufacturing sector by 2020. Colorado, the first state to legalize recreational marijuana, has already collected more than half a billion dollars since 2014. Earlier this year, Nevada generated $3 million in sales in the first four days that recreational marijuana was legal.

The protections of the Rohrabacher-Blumenauer amendment resumed with the passage of a temporary spending bill to reopen the federal government, but will sunset again on February 8th without another extension. Though the amendment was blocked by committee from reaching the full House for consideration in the House appropriation bill, the Senate did include the amendment in the Senate FY 2018 Commerce, Justice, and Science Appropriation bill. There is support for the amendment in the House; in late November, a bipartisan coalition of sixty-four representatives sent a letter to House and Senate leadership urging the amendment to be included in any appropriations bill beyond December 8th. This means that the fate of the protections of the Rohrabacher-Blumenauer Amendment may be in the hands of the reconciliation process of the House-Senate conference committees. A federal crackdown on marijuana is not very popular with voters; a recent Quinnipiac poll found that 70 percent of respondents oppose the government enforcing federal laws against marijuana in states that have legalized the drug for medicinal or recreational use; 91 percent of respondents support allowing adults to legally used marijuana for medical purposes if prescribed by a doctor. That may be an incentive for members of Congress to find a way to reinstate the amendment in some form.

Even if the limitations of the Rohrabacher-Blumenauer Amendment are extended, the Department of Justice has other tools they can use to disrupt state-legalized marijuana. Attorney General Sessions has stated that the Department of Justice will resurrect civil asset forfeiture, which allows police departments to seize property of those suspected of a crime (even if they are never charged or convicted), in part to target drug offenders. So even if the potential federalism showdown over Rohrabacher-Blumenauer is averted, another federalism conflict may by brewing.

The Trump administration’s approach to federalism is still revealing itself, but a move to crack down on medical marijuana could suggest a selective championing of states’ rights when politically advantageous. Though President Trump has previously said that “we need to make states the laboratories of democracy once again,” that practice has been enforced selectively in his administration.

In July 2017, Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced that the Justice Department would allow federal agency forfeiture, also known as “federal adoptions” of assets seized by state and local law enforcement agencies. The practice, an expansion of civil asset forfeiture, was curtailed by the Obama administration in 2015 by then-Attorney General Eric Holder. Though civil asset forfeiture is not necessarily well known to the public, the practice is unpopular across the political spectrum.

Civil asset forfeiture allows law enforcement officers to seize assets that they suspect, by a “preponderance of the evidence,” were involved in a crime. Unlike criminal forfeiture, where assets cannot be seized without a conviction, in civil forfeiture the person whose property is confiscated does not have to be convicted or even charged with a crime. The property, not the owner, is considered the defendant. Law enforcement is able to keep what is seized or keeps the profits if assets are sold off. Once property is seized through civil asset forfeiture, the burden of proof is on the owner to prove the property’s innocence by going to court. Unlike the more familiar judicial standard of innocent until proven guilty, assets seized though civil asset forfeiture are guilty until proven innocent. Civil asset forfeiture is big business; in 2014, the total annual dollar value of assets seized by federal law enforcement ($5 billion) surpassed total burglary losses ($3.5 billion).

Civil asset forfeiture has a long history, though the greatest increase in its practice coincides with the war on drugs of the 1980s. Proponents of civil asset forfeiture, such as Attorney General Sessions, argue that it “helps law enforcement defund organized crime, take back ill-gotten gains, and prevents new crimes from being committed, and it weakens the criminals and cartels.” Items such as illegal firearms and explosives that are taken through civil asset forfeiture are unable to be used in additional criminal activity. Civil asset forfeiture is also justified as providing material support to law enforcement, as proceeds from assets seized can be used by law enforcement to fund items like new vehicles, additional training, and bulletproof vests, making up for any budget shortfalls. Opponents to civil asset forfeiture argue that it is a violation of the constitutional right to due process and that by allowing law enforcement offices to financially benefit from the practice it creates an incentive to “police for profit.” There are also concerns that many innocent people are swept up in civil asset forfeiture and that it is rife with abuses, including using the money seized for such nonessential items such as margarita machines, tickets to sporting events, election materials, and holiday parties.

Civil asset forfeiture has always been somewhat controversial and several states have passed legislation to put limitations on its practice. Three states — North Carolina, New Mexico, and Nebraska — have abolished civil forfeiture entirely. Fourteen states (including North Carolina, New Mexico, and Nebraska) require a criminal conviction for most or all forfeiture cases. Fifteen states (including North Carolina and New Mexico) and the District of Columbia require that the government bear the burden of proof for innocent-owner claims. Other states have passed regulations that require reporting of seizures and final dispositions to state government agencies or limiting/prohibiting proceeds to law enforcement.

The federal adoptions provision that the Department of Justice reinstated, however, provides a loophole for law enforcement to get around any restrictions on civil asset forfeiture in their state. Under federal adoptions, state and local agencies can circumvent state laws on civil asset forfeiture by partnering with a federal agency to seize property that is believed to violate federal law. Up to 80 percent of the proceeds from equitable sharing is then returned to the state or local agency. Through federal adoptions, state and local law enforcement agencies are able to use the potentially more lenient federal standard of proof (“preponderance of evidence”) to seize assets that otherwise may be restricted by state statute. Marijuana dispensaries could be particularly vulnerable to being targeted through federal adoption, as the drug is classified as illegal by the federal government despite legalization in many states. The use of civil asset forfeiture and adoptive seizures, therefore, is not only an issue of civil liberties but also yet another federalism battle for the Trump administration

The Department of Justice directive to reinstate federal adoption of civil asset forfeitures may be prevented however. In September, the House of Representatives approved three amendments to a spending bill that would prohibit the Department’s ability to use funds on implementing the order. In November, a bipartisan group of senators sent a letter to the Senate Rules and Administrative Committee chairman and the ranking member of the Senate Small Business and Entrepreneurship Committee also urging the defunding of the implementation by the Department of Justice, because “Adoptive forfeiture and equitable sharing are particularly egregious elements of civil asset forfeiture because they not only violate due process but also attack principals [sic] of federalism.”

It remains to be seen if such efforts will ultimately limit the Department of Justice’s ability to expand the use of adoptive seizures, but it has created a rare opportunity for bipartisan agreement.

On January 4, 2018, Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced that the Department of Justice will rescind a policy that had previously allowed legal marijuana to expand in the states with limited interference from the federal government.

The policy, often referred to as the Cole memo, was implemented under the Obama administration and advised US attorneys that, “In jurisdictions that have enacted laws legalizing marijuana in some form and that have also implemented strong and effective regulatory and enforcement systems,” enforcement of federal law related to marijuana would not be a priority. While marijuana was still illegal under federal law, the Department of Justice would not generally disrupt the implementation of state marijuana law unless there was a compelling reason.

This laissez-faire approach allowed the legalization of both medical and recreational marijuana in the states to grow without being challenged by the federal government. By abandoning the policy outlined in the Cole memo, Attorney General Sessions is now giving U.S. attorneys the freedom to begin prosecuting people who violate the federal prohibition on marijuana, regardless of state law.

This reversal comes just days after California implemented the selling of recreational marijuana, which was voted into law in November 2016. While other states have also legalized marijuana for recreational use, California was seen as a watershed moment for marijuana policy because of its size; due to California’s population and economy, it became the largest market for legal recreational marijuana use in the country. According to predictions by the Agricultural Issues Center at the University of California, Davis, legalized recreational marijuana could add $5 billion a year to the California economy.

Massachusetts and Maine are poised to implement their recreational marijuana legislation in 2018 (approved by referendum in 2016 by 53 percent and 50.3 percent, respectively), while states like New Jersey, Michigan, and Vermont were expected to consider the issue sometime this year. A majority of the states will be impacted by this decision, adding fuel to a potential federalism showdown.

The decision by Attorney General Sessions to abandon the strategy outlined in the Cole memo does not come as a surprise, as Sessions has been a longtime opponent of marijuana, famously saying that “good people don’t smoke marijuana.”

However, for now, Sessions’s announcement puts the power in the hands of U.S. attorneys, who will ultimately have the discretion on whether to seek prosecution of those who violate federal drug law. This may result in even more confusion in marijuana policy, as some U.S. attorneys may decide to prosecute, while others may not. For an industry that already has uncertainty due to federal law, this could potentially introduce more chaos to the mix.

If the 2016 election was seen as a tipping point for marijuana policy in the United States, 2018 may be the breaking point. The détente that previously existed — where the federal government did not enforce federal law — is no longer possible, as the Department of Justice under Attorney General Jeff Session moves toward stricter enforcement of federal law, while states defiantly continue to expand state marijuana legislation. Eventually, something will have to give.

Already this year there have been major changes in marijuana policy with the decision by the Department of Justice to eliminate the enforcement priorities as outlined in the Cole memo. That action alone by the attorney general has prompted a lot of activity on both the state and federal level, as well as raising other potential issues for the burgeoning marijuana industry.

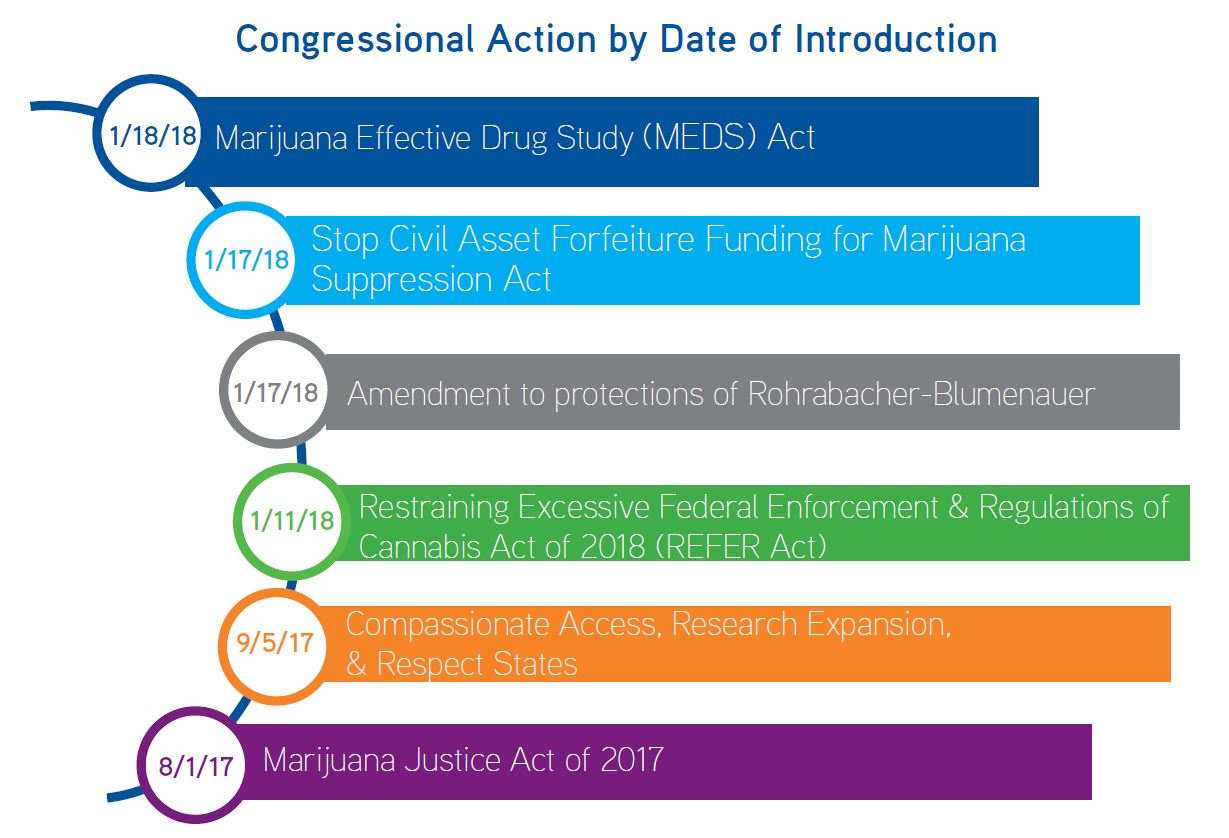

Several bills have recently been introduced in Congress that, if passed, would impact marijuana policy in the United States. The Restraining Excessive Federal Enforcement & Regulations of Cannabis Act of 2018 (REFER Act), sponsored by Representative Barbara Lee (D-CA), prohibits any US department or agency from using federal funds to prevent the implementation of state marijuana laws or to penalize financial institutions that provide services to state-permissible marijuana businesses or activates. The act is an expansion of the protections of the Rohrabacher-Blumenauer Amendment, which was applicable only to the Department of Justice and state medical marijuana laws and was subject to repeated renewal.

In August 2017, Senator Corey Booker (D-NJ) sponsored the Marijuana Justice Act of 2017, which would amend the Controlled Substances Act to remove marijuana from the schedule of controlled substances and legalize marijuana on the federal level. The act would also make states that have a disproportionate arrest rate of minorities or low-income individuals for marijuana offenses ineligible for some federal funds. Those convicted of a federal marijuana offense prior to the enactment of the act could be eligible for an expungement of their record or potentially reduced resentencing.

Senator Booker also introduced in September the Compassionate Access, Research Expansion, and Respect States (CARERS) Act of 2017. This bill seeks to protect state medical marijuana programs by amending the Controlled Substances Act to include the provision, “Notwithstanding any other provision of law, the provisions of this title relating to marihuana shall not apply to any person acting in compliance with State law, as determined by the State, relating to the production, possession, distribution, dispensation, administration, laboratory testing, recommending use, or delivery of medical marihuana.” The CARERS Act would also establish federal regulations to permit marijuana research and remove the current restrictions on the Department of Veterans Affairs discussing state medical marijuana options with veterans.

Senator Ted W. Lieu (D-CA) and Representative Justin Amash (R-MI) have introduced the Stop Civil Asset Forfeiture Funding for Marijuana Suppression Act, a bill that would prohibit funds from civil asset forfeiture being used to support the Drug Enforcement Agency’s Domestic Cannabis Eradication/Suppression Program and bars property from being transferred to a federal, state, or local agency if that property is to be used for any purpose pertaining to the Domestic Cannabis Eradication/Suppression Program. This is similar to a bill that the members introduced in 2015.

Representatives Jared Polis (D-CO) and Tom McClintock (R-CA) sponsored an amendment to be included in the next government funding bill that would expand the protections of the Rohrabacher-Blumenauer Amendment by prohibiting the Department of Justice from using federal funds to interfere with state marijuana law — medical and recreational. Though a bipartisan group of seventy House members sent a letter to congressional leadership supporting the amendment, the amendment was withdrawn from consideration because it seemed unlikely to have enough votes to pass the House Rules Committee. Committee Chairman Pete Sessions is an opponent of marijuana legalization. The amendment could resurface in future government funding bills.

Representative Rob Bishop (R-UT) introduced the Marijuana Effective Drug Study (MEDS) Act in the House of Representatives in January; Senator Orrin Hatch (R-UT) had introduced a version of the MEDS Act in the Senate in September 2017. The bill would make it easier for researchers to the medicinal uses of marijuana by streamlining the research registration process. The bill would also require the National Institute on Drug Abuse to develop guidelines for growing marijuana for research and would permit the commercial production of drugs developed from marijuana, pending approval from the Food and Drug Administration.

Despite the potential uncertainty facing state marijuana policies after the Department of Justice rescinded the Cole memo policy, states continue to move forward with marijuana policy expansion. Vermont became the ninth state to legalize recreational marijuana — the first state in the United States to legalize recreational marijuana through the state legislative process. All previous state recreational marijuana legislation has been passed by ballot initiative. The Vermont legislation is also unique in that, unlike other bills, it does not set up a commercial market for marijuana — buying and selling marijuana is still prohibited. Instead, individuals are allowed to possess up to an ounce of marijuana and have up to six marijuana plants at home.

New Jersey is also a likely candidate to pass recreational marijuana legislation in 2018. While former Governor Chris Christie (R) was an opponent of recreational marijuana legalization (New Jersey already permits medical marijuana), current Governor Phil Murphy (D) used his inauguration day speech to advocate for legislation. “A stronger and fairer New Jersey embraces comprehensive criminal justice reform — including a process to legalize marijuana.” Governor Murphy had previously stated that he would legalize marijuana within 100 days of taking office and New Jersey Senate President Stephen Sweeney (D) is reportedly confident that legislation will become law before April. However, the initiative is meeting some resistance from lawmakers on both sides of the aisle.

Legislators in the New Hampshire House of Representatives approved a bill this month that would legalize recreational marijuana in the state. Similar to the legislation in Vermont, the New Hampshire bill does not create a commercial market for recreational marijuana. The state had previously established a commission to study the impact of legalizing marijuana in the Granite State, but the commission’s final report is not expected until November 2018.

Kentucky took its first steps toward legalized marijuana this session with a pair of bills introduced in 2018. Citing budget concerns, state Senator Dan Seum (R) has introduced a bill that would legalize recreational marijuana in the bluegrass state. “It’s already out there, it’s always very available to anybody who wants it,” according to Seum. “So you legalize it, you tax it and the state gets the new revenue.” Meanwhile, state Representative John Sims (D) sponsored a bill in the Kentucky House that would legalize multiple forms of medical marijuana. Both bills likely face an uphill battle to passage; Governor Matt Bevin (R) is an opponent of marijuana legalization, stating, “We are not, while I’m governor, going to be legalizing the use of marijuana in this state for recreational purposes or for revenue-generating purposes.” A 2017 lawsuit that challenged the state’s ban on medical marijuana was thrown out of court.

A medical marijuana measure will appear on the ballot in Oklahoma during the June 2018 primary election. State Question 788 received enough signatures to appear on the 2016 ballot, but was held up by litigation over the initiative’s ballot title. That case was resolved in April 2017 and Governor Mary Fallin (R) announced the election date for the initiative in January 2018.

Supporters of legalized marijuana in Utah, Missouri, and, Michigan are working in 2018 on qualifying ballot measures for consideration by voters in their respective state elections. The proposed Utah ballot measure would focus on medical marijuana, while the proposed measure in Michigan would allow recreational use. Missouri potentially could have multiple initiatives in play, addressing both medical and recreational usage.

During his executive budget presentation, New York State Governor Andrew Cuomo (D) announced plans for a feasibility study examining legalizing recreational marijuana in the state, citing neighboring states moving forward with legalization as a factor. New York currently permits medical marijuana, but is among one of the most restrictive in the country, limiting use to creams, oils, and pills and prohibiting the drug in smokable forms.

While many new states are considering the issue of marijuana in 2018, it will also be an important year for the implementation of previously passed legislation. California began its recreational policy on January 1, 2018 and Maine and Massachusetts are expected to follow suit later this year. Other states considering legalization will be watching these states for potential best practices for their own potential implementation.

Marijuana policy is also likely to play a role in the various gubernatorial elections slated to take place in 2018. Candidates from both parties have taken public positions in favor of marijuana legislation reform, whether it be medical or recreational. Not all of these candidates will be victorious on Election Day, but the fact that marijuana policy has become a campaign issue for major party candidates is in and of itself somewhat significant.

There are also some court cases to watch in 2018 that could potentially have implications for marijuana policy in the United States. A lawsuit against Attorney General Sessions, the Department of Justice, the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA), DEA Acting Director Charles Rosenberg, and the United States of America alleges that:

…the Control Substances Act as it pertains to the classification of Cannabis as a Schedule I drug, is unconstitutional, because it violates the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment, an assortment of protections guaranteed by the First Amendment, and the fundamental Right to Travel. Further, Plaintiffs seek a declaration that Congress, in enacting the CSA as it pertains to Cannabis, violated the Commerce Clause, extending the breadth of legislative power well beyond the scope contemplated by Article I of the Constitution.

The plaintiffs in the case include a former NFL-player who wants to expand his business to include Cannabis-based medications, children who use medical marijuana to control seizures and alleviate pain, and a veteran who wants to use marijuana in treatment of his Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). If this challenge is successful, the marijuana provision of the Controlled Substances Act would be overturned, which could pave the way for nationwide legalization. The Southern District Court of New York is hearing the case and oral arguments are scheduled for February 2018.

Several civil cases that are currently working their way through the judicial system could be a deterrent to legal marijuana businesses. Suits filed in Colorado, Oregon, and Massachusetts by neighbors of these business alleged that the proximity of said business have hurt property values, interfered with enjoyment of property, increase the likelihood of criminal activity, and brings a stigma to the neighborhood. Since marijuana is a violation of the federal Controlled Substances Act, these cases allege a violation of the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO) and seek damages not only against the marijuana businesses, but their property managers, financial institutions, and investors as coconspirators. Coconspirators can be found financially liable even if they were not directly responsible for the claimed injuries.

When the Department of Justice abandoned the guidance of the Cole memo, they also upended the regulations that permitted banks and credit unions to work with marijuana businesses. The foundation for the Department of the Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network guidelines for financial institutions were based on the Cole memo. Without that memo as a guidepost, it is unclear what the policies will be in the future. During testimony at a hearing of the Senate Banking Committee, Sigal Mandeker, the Treasury Department’s undersecretary for terrorism and financial crimes, indicated that while the guidance currently remains in place, they are “reviewing that guidance in light of the DOJ’s reversal of the Cole Memo.” Members of the House and the Senate have sent letters to the Department of the Treasury in support of maintaining the current guidelines.

Additionally, eighteen state attorneys general sent a letter to congressional leaders urging them to pass legislation that would continue to allow financial institutions to provide services to businesses in the marijuana industry. Without clear guidance from the federal government, financial institutions may be hesitant to work with state-licensed marijuana businesses out of fear of criminal or civil prosecution. If forced to operate as a cash-only business, marijuana dispensaries may increasingly become targets of theft and are more vulnerable to civil asset forfeiture.