This analysis is part of the “Epidemic in a Pandemic” series that looks at what has happened to substance-use treatment access and effectiveness during COVID-19.

When we recently examined CDC mortality data from 2018 to better understand the first decline in overdose mortality in 20 years, our closer look at that decrease revealed a disturbing increase in overdose deaths attributed to methamphetamine (meth) and cocaine. Once more, provisional data for 2019 shows that meth overdose deaths have continued to rise, as cocaine deaths have leveled out, and are expected to rise further as data from the second half of 2019 and 2020 are reported.

This increase in methamphetamine deaths is particularly worrisome as meth use has increased both in parts of the country where it was less traditionally available and in areas that are already hard hit by the opioid epidemic. Meth use, however, requires different types of public health interventions than opioid use. There is no equivalent to the lifesaving overdose blocking drug naloxone or the medication assisted treatment (MAT) drugs methadone and buprenorphine.

While overdoses attributed to meth remain lower than those attributed to opioids, focusing on overdose deaths alone underestimates meth mortality. Unlike opioids, which have relatively less risk of long-term health impacts to users who do not overdose, meth can cause rapid and severe physical and psychological deterioration in its users. Consequently, many users who die from health problems caused by methamphetamine use disorder (MUD) do not show up in overdose mortality data. In this piece, we dive into the physical, mental, and social effects of meth, the populations and places it affects and public health and public policy responses to its spread.

Signs of an Epidemic

Increases in specific-drug mortality are one of the key indicators that public health officials use to identify drug use epidemics. However, overdose mortality data are imperfect predictors of a looming meth epidemic for two reasons. First, official CDC data generally lags by one to two years, and provisional data lags six months to a year. Second, a substantial amount of the death, physical harm, and social harm inflicted by meth is not reflected in overdose statistics because people with MUD are more likely to die of physical and mental diseases related to their meth use than they are to die from a meth overdose, and those deaths are not tied to meth in mortality records.

A number of nonmortality metrics show meth use is increasing in the US. According to the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 1.1 million people reported meth use, almost twice the number who reported heroin use. A large sample of urinary drug tests (UDTs) across all 50 states found that meth positives increased from 7.2 percent in 2018 to 8.4 percent in 2019, but the long-term trends are even more stark. There has been a sixfold increase in positive methamphetamine tests since 2013. Opioid use, by comparison, has declined from 2018 to 2019.

There has been a sixfold increase in positive methamphetamine tests since 2013.

There is also substantial evidence of an increase in meth use among people using other types of drugs, including a disturbing increase in the percentage of fentanyl positive tests that also contain methamphetamine. Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid responsible for the extreme spike in overdose deaths in 2016. Likewise, a study of heroin treatment found that there has been a substantial increase in over a decade in the percentage of people that are seeking treatment for heroin use disorder who also report methamphetamine use—up from only 2 percent to 12.4 percent or nearly 1 in 8.

Physical, Neurological, and Social Effects

As referenced above, overdose deaths tell only half the story of meth mortality. Individuals with Methamphetamine Use Disorder (MUD) have a higher all-cause mortality risk due to the physical, neurological, and social effects of use than cannabis, cocaine, or alcohol use disorder, though it has lower risk than opioid use disorder (OUD).

Methamphetamine is the most common member of a larger family of drugs the CDC categorizes as psychostimulants with abuse potential. These are synthetic drugs, including a number of different amphetamines, manufactured in labs using precursor chemicals and a predictable set of reactions and steps to create an amphetamine. Although there are multiple processes that leave different chemical markers and levels of purity, the final product is an addictive stimulant that acts on both the nervous and cardiovascular systems.

Meth, and other amphetamine, addiction works both through the neural systems and biological pathways. Meth is extremely harmful to health beyond the potential for addiction. Meth has been shown to induce psychosis and other mental disorders, cause cardiovascular dysfunction and renal failure, and suppress appetite to the point of causing malnutrition and vitamin deficiency. These effects are long lasting and cause substantial health problems even after a person stops actively using meth.

Another side effect of meth is lowered inhibitions and increased energy. Lowered inhibitions, in particular, can exacerbate other health problems and lead to disease transmission. People under the influence of meth are less likely to be able to manage chronic medical conditions and more likely to take risks leading to injury or to contracting STIs and other blood borne illnesses.

…people with MUD are more likely to die of physical and mental diseases related to their meth use than they are to die from a meth overdose, and those deaths are not tied to meth in mortality records.

Meth also has a different relationship to violent behavior and violent crime than opioids. Whereas opioids are depressants and reduce heart rate and breathing, leaving users lethargic while they are high, the high potency and purity of meth results in energized users who are often reported to be jumpy and may become psychotic or violent. Meth users are also more likely to become victims of violence and violent crime.

Production and Distribution

During the first wave of the meth epidemic in the US (during the 1990s and early 2000s), most available meth was made near its users in small batches and small labs. The primary precursors were the over-the-counter decongestants ephedrine and pseudoephedrine. That meth was generally of low potency and low purity. After sales of ephedrine and pseudoephedrine were strictly limited in 2006 by the Combat Methamphetamine Epidemic Act of 2005 (CMEA), local production was cut substantially. According to the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), meth lab seizures in the US peaked in 2004 with approximately 23,703 incidents. By 2018, there were only 1,568 domestic seizures and 85 percent were considered very small operations only capable of producing two ounces of meth or less.

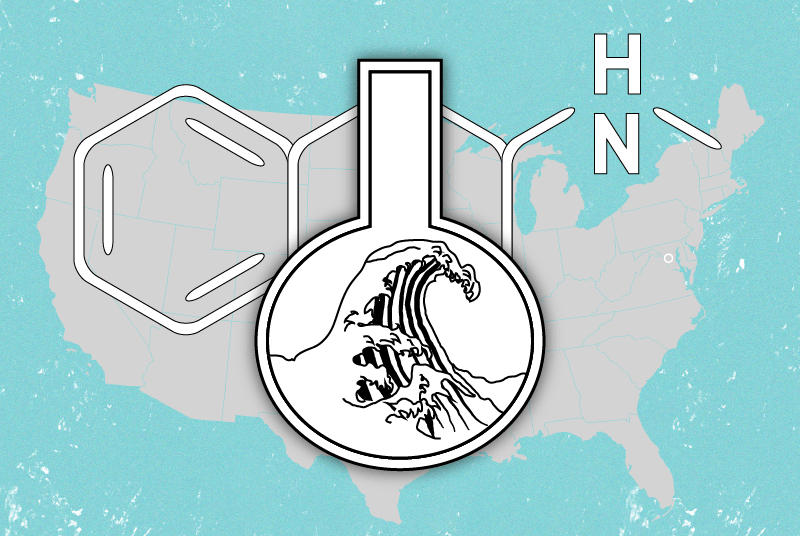

The current wave of meth, however, is purer, more potent, and cheaper than the first wave. This wave also tends to be imported from Mexico rather than manufactured locally because of the strict restrictions on precursor chemicals in the US. Most meth currently available in the United States is made using the phenyl-2-propanone or “P2P” production method which gives the drug a more “euphoric” effect, which can lead users to turn to it when they do not have supplies of opioids. The DEA reports that meth seized in 2018 was relatively cheap and pure with an average purity of 97.5 percent and average potency of 96.9 percent. The price is at an all-time low of $56 per pure gram. This is cheaper, more potent, and more pure than the meth available in the 1990s and early 2000s. It is also cheaper and more potent than five years ago.

Geography

The first wave of the meth epidemic in the 1990s and early 2000s was worst in the southwestern US and that region remains a hotspot for meth overdose deaths. Nevada, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Arizona, and Utah all have meth mortality rates greater than 7 in 100,000. New hotspots have also emerged outside the southwest, largely in places hit hard by the opioid epidemic including West Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, Indiana, and Ohio. West Virginia currently has the highest meth mortality rate in the country at 20 deaths per 100,000 people, largely because of mixtures of meth and other opioids such as fentanyl.

Using our data visualization, it is easy to see how this current wave of meth related mortality has spread through the country from the southwest. A simple way to look at the geographic spread of meth is to identify the first year in which a state had a meth mortality rate over 5 in 100,000 deaths. In 2011, there was only one state that met this benchmark, Nevada, and by 2018 there were 18 states. Using this measure, the meth epidemic initially spread from Nevada to neighboring New Mexico in 2014, expanded through the southwest in 2015 and 2016 to Oklahoma, Arizona, and Utah and also jumped to Washington, Alaska, Hawaii, and West Virginia. In 2017 and 2018, the expansion of meth mostly took place in states that were already hard hit by opioids, including Tennessee, Kentucky, Ohio, and Indiana.

Meth has spread to traditional opioid hotspots like southern Ohio and northern Kentucky, with opioid users turning to meth as supplies of prescription opioids and heroin dry up or are viewed as “unsafe” when mixed with fentanyl. The drug taskforces funded through the Ohio High-Intensity Drug Trafficking area saw a 1,600 percent increase in meth seized from 2015 to 2019. Cities like Louisa, Kentucky and Concord, New Hampshire, which were hit extremely hard by opioids, have seen meth return with a vengeance this year. In Concord, meth now accounts for 60 percent of drug seizures. State police near Louisa say 8 in 10 arrests are related to meth use.

Meth also has the potential to tick opioid overdoses back up. If people addicted to opiates turn to meth after recovery because it’s more available, seems different, or safer somehow, coming down from meth will make them more likely to seek out their drug of choice again and result in relapses.

Recent evidence points to meth beginning to move into the Northeast US, a place where it has traditionally been eclipsed by cocaine. Burlington, Vermont has seen a dramatic uptick in overdoses since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, resulting in part from mixtures of meth and fentanyl. Concord, New Hampshire has also seen substantial growth in meth, which now accounts for 60 percent of drug seizures.

There is also evidence that the production of meth is changing in order to break into new markets. The DEA reports that meth in pill form, rather than the more common crystalized version, has been found in several states including Illinois, New Jersey, Ohio, Virginia, Michigan, and South Carolina. These pills were often disguised as other drugs including MDMA and Adderall.

Vulnerable Populations

Native American communities have been some of the hardest hit by the meth epidemic. While meth is often depicted as a rural white drug, its long presence in the southwest of the US has lent to its availability and use on reservations in the region and it has begun to show up in Native American communities in the Midwest as well. Thirty-nine percent of overdose deaths among Native Americans in 2018 were attributed to meth. That is over twice as high as the rate for white Americans. The President of the Oglala Sioux Tribe has declared a state of emergency over homicides and meth use on the Pine Ridge Reservation and the FBI has attributed a 2016 spike in homicides there to meth use and distribution.

Recent meth use also appears to be relatively high among gay men, bisexual men, and men who have sex with men (MSM) more generally. It is harder to track the impact of MUD among gay men and men who have sex with men, as national statistics on overdose mortality and survey data generally are not broken up by sexual orientation or sexual history. However, research has found a resurgence in meth use among MSM. Estimates for the extent of meth use among MSM vary, but there is general agreement that it is 25-45 times the rate of the general population. There has been a recent push to recognize and address the impacts of meth on MSM including an op-ed in the New York Times.

Treatment and Policy Responses

The good news is policymakers and public health officials have better tools to tackle addiction now than during the last meth epidemic. The size and scope of the opioid epidemic expanded funding for and research into effective addiction treatment. Policies to mediate harm and treat the underlying addiction disorder are now far more common than before and have real promise for treating meth addiction as well.

Unfortunately, there are no pharmacotherapies available that limit or reduce stimulant use and the psychosocial interventions that are available have a weak overall effect. There is some evidence that cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) can be effective at treating meth addiction in certain populations. In a randomized control trial, women receiving methadone (an opioid medication treatment) for OUD who also use meth were more likely to test negative for meth, used meth less, and showed other significant psychological improvements compared to those who only received drug education. Another evidence-based treatment is “contingency management,” which provides incentives for abstaining from meth.

A substantial difference in MUD compared to opioid use disorder (OUD) is that the overwhelming health concern of OUD is overdose, so avoiding overdose deaths and getting users into treatment may be effective at mitigating much of OUD’s physical harms. This is less true for meth. Meth is most likely to cause death through long-term cardiovascular and neurological damage. Preventing an overdose and entering into treatment, even lifetime future abstinence, can result in someone still dying from meth-related health problems. This may make safe consumption sites less attractive as a policy, although these sites can provide other types of treatment such as clean needles to prevent transmission of STIs.

Recognizing and treating the physical and mental impacts resulting from MUD, even after a person stops using, is extremely important. Cities like San Francisco are confronting meth directly. The city’s methamphetamine task force singled out three specific recommendations including creating a trauma-informed sobering site with harm reduction services, strengthening the city’s interdisciplinary behavioral health crisis response, and prioritizing housing for people seeking treatment.

The federal government has also very recently stepped in to provide states with some flexibility and assistance in addressing meth and cocaine use. Federal action on methamphetamine has been minimal since the passage of CMEA in 2005 with most of the focus going to the opioid crisis. However, in late 2019 a spending bill agreement broadened the scope of the $1.5 billion grant program, previously restricted to opioids, to counter stimulant addiction, particularly meth and cocaine.

Although attention to drug epidemics comes in waves, in reality substance use often contains a combination of drugs and alcohol. The increased prevalence of meth suggests meth is becoming the next serious epidemic. It is important to keep the valuable lessons from the opioid crisis on how to treat the totality of addiction, including underlying trauma, in addition to physical substance dependence. The federal government has taken an important first step in expanding funding, and states and municipalities need to expand their addiction services as well to prevent an increase in meth use from overwhelming a decline in opioid use.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Leigh Wedenoja is a senior policy analyst at the Rockefeller Institute of Government