During my tenure as Chancellor of SUNY, we worked to get the entire 64-campus system focused on one thing: college completion. We set a goal to increase the number of degrees we awarded annually from 93,000 to 150,000. We mobilized the troops, took programs that were improving student outcomes at some campuses and brought them to others, and found money to support improvement efforts even during tough financial times.

Were we successful? I don’t know. There definitely were many bright spots, many promising programs put in place, and lots of reasons to hope. But it will take a while to find out if any of it truly moved the dial for the long term.

One thing I learned is that when it comes to getting students to and through college successfully, we in higher education need a big dose of getting our act together.

“We need to get better. Indeed, it is our obligation to become the best at getting better.”

The college completion puzzle is a complex one to be sure. But if NASA could put a man on the moon almost 50 years ago, surely colleges and universities can get better at graduating lots more students – students of all kinds – today.

A recent Gallup Poll[1] showed that, thankfully, a good chunk of the public still has confidence in the promise and benefits of “higher education,” generally speaking. But their faith that the actual institutions of colleges and universities are delivering a quality and success-breeding learning experience is slipping.

Why is this?

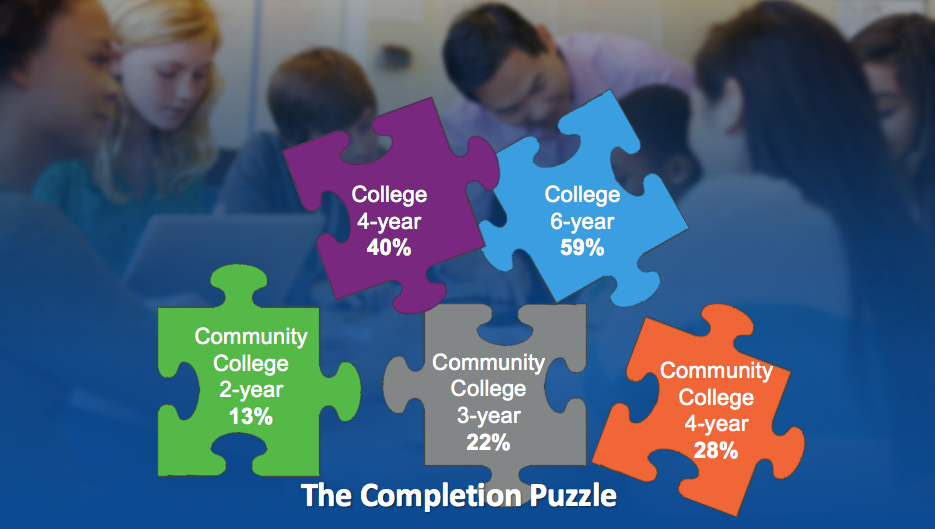

Maybe it’s because only 40 percent of students at what are called “four-year colleges” actually graduate in four years. And only 59 percent of them do so after six years, the now too-accepted “150 percent of normal time” measure.[2] For our nation’s community colleges, the data are even more halting: the two-year graduation rate is 13 percent; after three years it’s 22 percent, and by four years it is still only 28 percent.[3]

The six-year graduation rate for Hispanic students is almost 10 percentage points lower than for white students, and for African-American students it’s almost 25 percentage points lower.[4] Fewer than half of recipients of federal Pell Grant, typically low-income students, ever complete college. [5] Seventy percent of students who are assigned to remedial courses when they first come to college never graduate.[6]

Houston, we have a problem.

We have tried various fixes, of course. Maybe we haven’t done the right things or done them in the right way. Or maybe we just haven’t tried hard enough. Consider this timeline:

- In 2008, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation announced a goal of doubling the number of low-income students with a postsecondary degree or certificate by the age of 26 by 2025. Gates supported hitting this target with massive philanthropic investment. The Lumina Foundation also set a goal to increase the percentage of Americans with high-quality degrees and credentials to 60 percent by 2025.

- In 2009, President Barack Obama proposed the American Graduation Initiative, focused on a goal that by 2020 America should have the highest proportion of college graduates in the world.

- In 2009, the interstate alliance Complete College America was formed to try to centralize data, replicate best practices, and coalesce effort on states’ completion initiatives.

- In 2011, another multi-million-dollar federal program was announced that was designed to increase college success and productivity.

- By 2011, the American Association of State Colleges and Universities highlighted more than a dozen major national college completion initiatives. (Another study in 2017 cited nearly double that number.)

- In 2012, hundreds of millions of dollars in federal funds were proposed to support programs and systemic reforms designed to boost completion rates.

- Following Gates’s and Lumina’s lead, other private philanthropic organizations including Ford, Carnegie, and W.K.Kellogg stepped up big and funded dozens of college completion initiatives.

- Most recently, APLU aligned their existing degree completion initiatives into the Center for Public University Transformation to focus efforts and accelerate shared goals.

- Currently, at least 40 states have adopted formal goals for college completion rates.

So what has happened after all of this?

Since 2008, the percent of American adults graduating from a post-secondary institution increased from just under 38 percent to not even 42 percent in 2016, a measly increase of 4 percent over almost the past decade. Add in another 5 percent or so of adults who hold professional certificates, and the amount of our country’s adult population with any sort of post-secondary attainment still falls short of 47 percent.[7]

At our current rate of improvement, if one can really call it that, college completion targets originally set for the years 2020 and 2025 now won’t come close to being met until the years 2037 and 2054.

Houston, we actually have a crisis. That’s generations of students we’re losing because we’re not getting the improvement we envisioned. We need to do so, so much better.

So let’s get to it.

Solving the college completion puzzle will take strong leadership at even our most prominent colleges and universities, including a bold willingness to disregard those annual rankings by popular periodicals, ratings that have more to do with prestige than actually serving students.

According to U.S. News and World Report’s college ranking methodology, more than half of the total score it uses to rate colleges is comprised of components that have nothing at all to do with completing college, let alone graduating on time or with a degree that leads to success in graduate school or the workforce.[8] Chasing ratings is a problem for other reasons, too. For example, an economist at Cornell University explained that tuition at that institution has risen so high to maintain its place on U.S. News’s roster because “any slippage in the ratings is extremely costly to the institution.”[9] And still another team of researchers at an excellent private university rated in the mid-30s calculated that to move up just one place on U.S. News’s rankings, their school would have to spend more than $100 million each year on increased faculty compensation and spending on students.[10] One hundred million dollars per year for one higher spot.

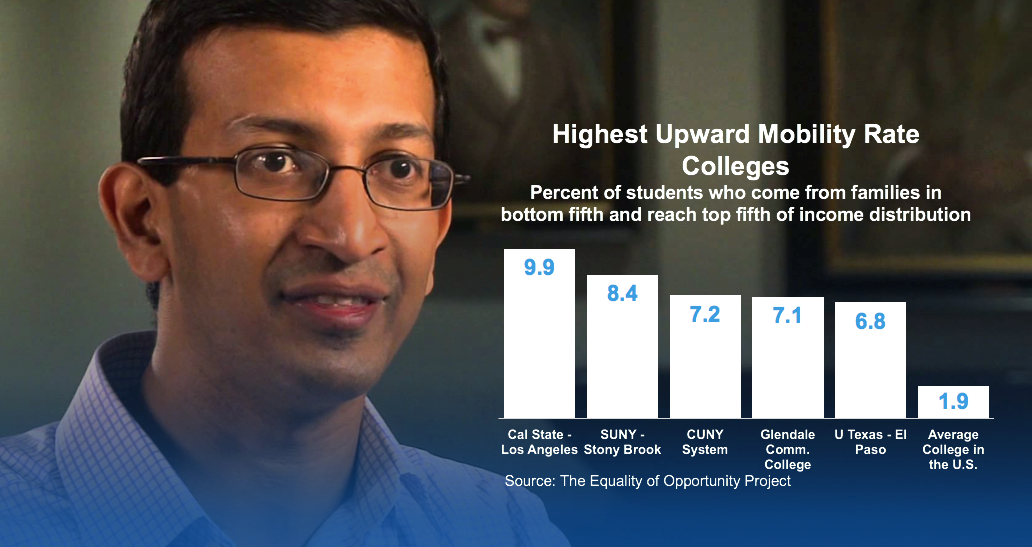

Colleges and universities need to pick – and fully embrace – a better target. We need to pay attention to researchers like Raj Chetty with the Equality of Opportunity Project at Stanford and his Mobility Report Cards.[11] This innovative, student-centered approach measures which schools have the greatest success educating students coming from families in the lowest-fifth of annual income – a way to ensure that access to good schools for low-income students is valued – by what proportion of those same students end up in the top-fifth of income distribution after college. Now that’s a measure of how higher education can truly effect socioeconomic mobility.

Maybe, just maybe, we’re making some progress in this direction. For the first time ever, in its most recent college rankings list Money Magazine included as a measurement component a school’s score on the Mobility Report Card. At just 7 percent of the total score, Money Magazine is just dipping its toe in the water. Who knows? Maybe next year this or another of the popular periodicals will be willing to jump right into the deep end of the pool and give this measurement the significance it deserves.

Meeting the challenges of college completion will take a commitment from colleges and university systems all across the nation to work together, to bind together all the various well-intentioned initiatives into a consolidated, coordinate effort to get more students to and through college. Taking the “thousand points of light,” as it were, and turning them into a single laser beam focused on this one goal. We need to maximize the potential of collective impact.

That takes us in higher education all sitting together at the same table, dropping our individual agendas, and jointly committing our efforts and actions to this one shared goal. It takes us promising to collect good data – and share it – and then use it all the time to make evidence-based decisions about what is really working and understanding why. We must commit ourselves to rigorous and continuous improvement, using proven and science-based strategies for self-examination to change for the better year after year.

Frankly, it will take what colleges and universities are supposed to have been doing all along.

We see the dramatic success of collective-impact efforts in programs such as StriveTogether’s K-12 improvement initiatives, and the 100,000 Homes Campaign’s homeless housing effort, and the Elizabeth River Project’s environmental clean-up, and Milwaukee’s Baby Can Wait teen pregnancy-reduction effort. Our country’s top philanthropists have recognized continuous improvement as an approach that works – the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation with its latest $1.7 billion pledge to support Networks of School Improvement, and Steve and Connie Ballmer’s nearly $100 million gift to StriveTogether, for example.

It is long past time for us in higher education to take a similar approach, to determine our theory of action and embrace the power of collective impact.

I was honored to deliver the keynote speech this weekend at the 100-year anniversary conference of the American Council on Education, which bills itself as “the nation’s most influential, respected, and visible higher education association.” Before the conference, Ted Mitchell, ACE’s new leader, said to me: “100 percent of the students who go to college intend to graduate.” He’s so right. What it also means, I beg us all to realize, is that any college or university that fails to reach that goal has fallen short.

We need to get better. Indeed, it is our obligation to become the best at getting better.

We owe that to every student who is in college, and to every student who is thinking about going to college. And we owe it to every student yet to step foot in their first kindergarten classroom.

Not just to 60 percent of them.

Footnotes

[1] http://news.gallup.com/poll/228182/words-used-describe-higher-difference.aspx Also see: https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2018/02/26/public-expresses-more-confidence-higher-education-colleges-or-universities

[2] https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d16/tables/dt16_326.10.asp

[3] https://www.communitycollegereview.com/blog/the-catch-22-of-community-college-graduation-rates and http://ncee.org/2013/05/statistic-of-the-month-comparing-community-college-completion-rates/. The National Center for Education Statistics calculates the 3-year community college graduation rate at 29 percent – see: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d16/tables/dt16_326.20.asp and https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_ctr.asp. Another NCES study puts the 3-year completion rate at 28 percent (see: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/raceindicators/indicator_red.asp). Yet another NCES study puts community college graduation rates at: 2-year, 18 percent; 3-year, 30 percent; and 4-year, 35 percent. See: https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2017/2017084.pdf

[4] https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d16/tables/dt16_326.10.asp. For an alternate data source, see: https://nscresearchcenter.org/signaturereport12-supplement-2/

[5] http://time.com/money/4981302/low-income-students-pell-graduate/

[6] https://www.citylab.com/life/2017/02/why-millions-of-americans-never-finish-college/517713/; and https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/Community-College-FAQs.html

[7] http://strongernation.luminafoundation.org/report/2018/#nation

[8] https://www.usnews.com/education/best-colleges/articles/ranking-criteria-and-weights

[9] CollegeNET’s Social Mobility Index, at: http://www.socialmobilityindex.org/

[10] https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2014/06/03/what-would-it-really-take-be-us-news-top-20#ixzz37KhtDUg0