How the US Developed an Opioid Problem

How did opioids become a problem in the United States? It’s a question that many people are asking and that most newspapers purport to know the answer to, at least if you read the headlines. Opioids became a problem in the early 1990s when big pharmaceutical companies tried to boost profits by pushing the sale of painkillers. People eventually got hooked, but when they lost access to prescription medications they turned to heroin as a cheaper, more accessible alternative.

This is a common story told about the origins of America’s opioid epidemic, and it is probably a story you’ve heard once or twice before. But does it really tell the whole story?

In an effort to answer that question, we traveled to Sullivan County, which has one of the highest opioid death rates of any county in New York State, to consult with community members, public health officials, and the families of people struggling with addiction. Although many people agreed that prescription drugs and the pharmaceutical companies are largely to blame for the current crisis, this narrow focus on painkillers ultimately obscures other parts of the story we heard about legitimate injuries, recreation, and self-medication. In short, it misses the broader sociocultural and economic changes that have coalesced alongside a shift in physicians’ prescribing practices to lead America down the road to addiction. In this blog, we unpack the national narrative surrounding the opioid crisis in the United States, and then adjust it to account for what we heard on the ground in Sullivan County.

How Did Opioids Become a Problem?

The National Narrative

Americans moved from prescription opioids to heroin and now fentanyl.

Nearly every account of the opioid crisis in America begins in the early 1990s, when large pharmaceutical companies sought to boost profits by increasing the sale of prescription opioids. Indeed, while many doctors feared the addictive properties of drugs designed to minimize pain, companies like Purdue Pharma set out to change physicians’ prescribing habits by aggressively marketing and promoting their drugs. As early as 1995, the Food and Drug Administration approved Purdue Pharma’s pain reliever OxyContin, and other opioids like it, for the purpose of treating moderate-to-severe pain lasting over extended periods of time (GAO 2003). Although organizations like the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research believed that such drugs could be used to improve long-term treatment of cancer pain, companies like Purdue hired hundreds, if not thousands, of sales representatives to push the drug on primary care physicians — physicians who treated conditions other than cancer including arthritis, injuries, and chronic back pain (Keefe 2017). Their efforts paid off. By 2001, sales of OxyContin exceeded $1 billion annually, and the drug became “the most frequently prescribed brand-name narcotic medication for treating moderate-to-severe pain in the United States” (GAO 2003).

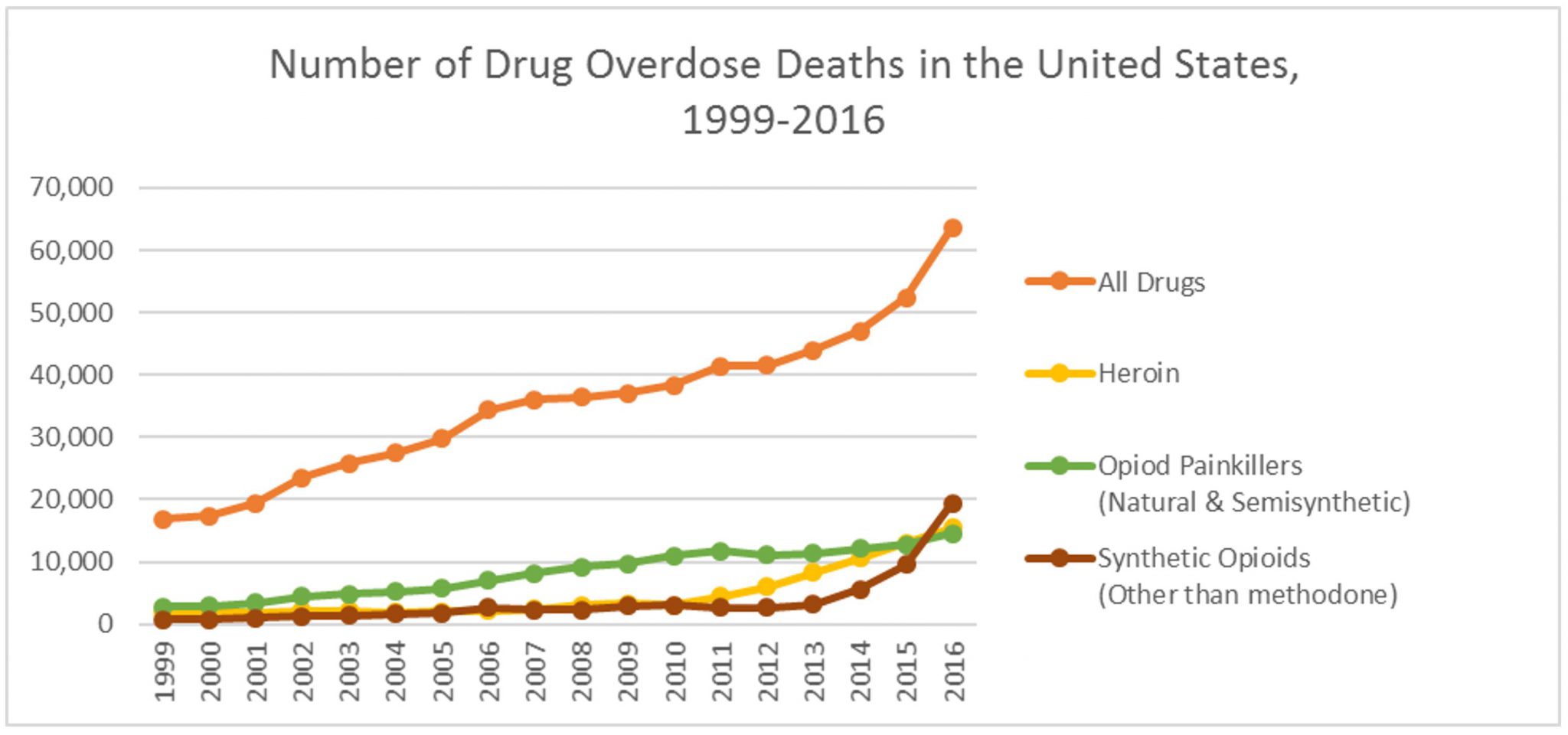

Consistent with what has been described as a “coordinated, sophisticated, and highly deceptive marketing campaign,” designed to convince “doctors, patients, and others that the benefits of using opioids to treat chronic pain outweighed the risks,” the sale of prescription opioids skyrocketed in the United States (County of Sullivan vs. Purdue Pharma L.P., et al. 2017). Between 1999 and 2010, sales of opioid pain relievers nearly quadrupled (Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2011), fueling an increase in the number of opioid-related deaths. During the same eleven-year period, opioid-related deaths climbed steadily from 8,050 in 1999 to 21,089 in 2010 and beyond. By 2016, estimates from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention indicate that between 1999 and 2016 opioids claimed the lives of more than 350,000 Americans.

Alarmed by the growing number of deaths, state and federal officials sought to restrict access to painkillers, or so the narrative continues. In 2016, Massachusetts became one of the first states to limit the duration of first-time opioid prescriptions to seven days. In little over a year, the National Conference of State Legislatures found that twenty-three states enacted similar legislation, with prescribing limits ranging anywhere from three to fourteen days. Prescription drug monitoring programs (which seek to improve opioid prescribing) and dosage limits (which penalize healthcare providers who prescribe patients more than a certain amount of opiates) are two additional examples of state-level interventions designed to control the supply of opiates. For its part, the federal Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) announced in October 2016 that it would reduce the manufacture of almost every opioid pain medication in the United States by a minimum of 25 percent. Although many people celebrated these supply-reduction efforts as a necessary first step in the war against opioids, others warned about their effects on people already struggling with addiction. Indeed, for the men, women, and teenagers already dependent on prescription opiates, limited access to painkillers created a new problem — finding more money to buy more expensive pain pills on the street, or tracking down a cheaper, more accessible alternative. For many, the solution was heroin.

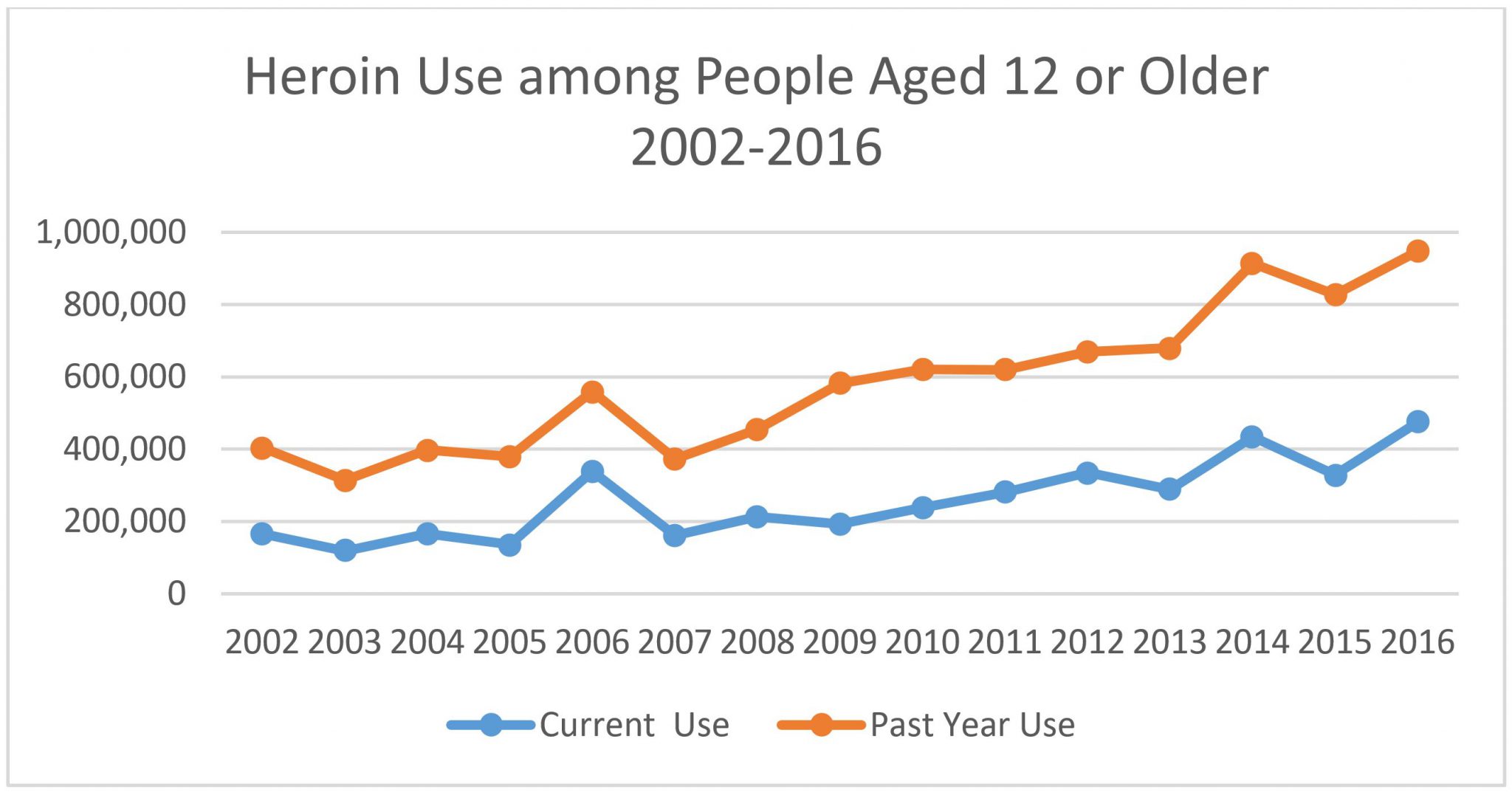

A rise in the use of heroin seems to bear this out. According to The National Survey on Drug Use and Health, heroin use in the United States has steadily increased since 2007, with only a few exceptions. Because heroin consumption is not as common as the use of other illicit drugs, the survey includes estimates for both current (past month) and past year use. Throughout 2016, an estimated 948,000 people aged twelve or older used heroin (see figure below). Although this figure was comparable to the estimates reported in 2014 and 2015, it was still higher than the estimates reported each year between 2002 and 2013 (NSDUH 2017). Not surprisingly, the number of heroin-related deaths has also climbed. “Between 2002 and 2013, the rate of heroin-related overdose deaths nearly quadrupled,” with more than 15,000 deaths occurring in 2016 alone (CDC Heroin Overview).

Source: 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health.

Note: Current use indicates those individuals who reported using heroin in the past month, whereas past year use represents any individual who reported using heroin within that year.

Although heroin claimed the lives of more people in 2016 than in any of the previous fifteen years, fentanyl — which is a powerful synthetic opioid that is “fifty to one hundred times more potent than morphine” (CDC Fentanyl) — proved even more deadly. Over the past several years, the rate of overdose deaths involving fentanyl and other synthetic opioids doubled from 9,580 deaths in 2015 to roughly 19,400 in 2016, making fentanyl the deadliest opioid now available in the United States (see figure below).

Source: Centers for Disease Control Data Brief

Note: “All drugs” includes accidental and intentional poisoning by all drugs and biological substances; “opioid painkillers” includes drugs such as morphine, Oxycodone, and Hydrocodone; and “synthetic opioids” includes drugs like fentanyl, fentanyl analogs, and tramadol, but excludes methadone.

So what explains this move from prescription painkillers to heroin and now fentanyl? The common explanation outlined above is that cracking down on prescription opiates has shifted the market to more dangerous drugs like fentanyl. As one senior Vox news reporter put it: “If you go after opioid painkillers, people will eventually go to heroin. If you go after heroin, they’ll eventually go to fentanyl. And if you go after fentanyl, they might resort to some of its analogs, like carfentanil.” Admittedly, this logic makes sense. It assumes that whenever individuals lose access to prescription painkillers they are forced into the streets to buy stronger, cheaper alternatives. However, this explanation is too simplistic for understanding the complexities of the current opioid crisis. Although the increasing number of deaths does raise questions about the utility of supply-reduction efforts, this common narrative concerning the transition from painkillers to heroin and now fentanyl fails to account for a variety of other factors that have contributed to the current opioid crisis. These include rapid increases in heroin production; changes in the distribution strategies of drug traffickers; and broader patterns of drug addiction throughout the United States.

Cheap Heroin Floods the Market

With respect to the supply-side economics of addiction, a substantial increase in the availability of heroin has created new opportunities to abuse it. As the DEA observed in its 2017 National Drug Threat Assessment: “Rapid increases in heroin production in Mexico since 2015 have ensured a reliable supply of low-cost heroin, even in the face of significant increases in user numbers.… This increase was driven in part by reduced poppy eradication in Mexico and Mexican organizations’ shift to increased heroin trafficking.” What this means in the context of the United States is that more people have access to heroin than ever before. According to research published in Addictive Behaviors, an increasing number of people are experimenting with heroin as their first opioid, rather than transitioning from painkillers to heroin, as the dominant narrative would suggest. In 2005, less than 10 percent of people who were dependent on opioids used heroin first. However, a decade later, that number increased to a third, making heroin “the leading drug for new opioid initiates.” As one observed, a dealer-driven increase in supply “gave more people new opportunities to try heroin even if they weren’t addicted to painkillers.”

Changes in the way drug traffickers are doing business have also contributed to the rising number of deaths, particularly with respect to the sale of fentanyl. While prescription fentanyl — which takes the form of patches or lozenges — is sometimes diverted from healthcare facilities, it is more common for powdered forms of the drug to be illicitly manufactured in China and Mexico and then smuggled into the United States. Once here, powdered fentanyl is mixed into heroin, oftentimes without the buyer’s knowledge, or pressed into counterfeit pills resembling Xanax, Oxycodone, and other opioid medications. When used as a cutting agent in heroin, fentanyl “looks like heroin, is packaged in the same baggies or wax envelopes as heroin, and displays similar stamps or brands as heroin.” From a dealer’s perspective, the logic is simple. By mixing fentanyl with other adulterants including sugar, dealers can sell less heroin for the same price and oftentimes with the same effect. In fact, the DEA has observed that an increasingly large amount of fentanyl is being sold as heroin, even when there is no heroin in the product.

Although most people who are exposed to fentanyl are unaware that it was used to cut heroin, there is some anecdotal evidence to suggest that others actively seek the drug. When we asked folks in Sullivan County about whether people know they are being sold fentanyl, one retired probation officer told us that some people go look for it. When a death occurs, rather than alert people to avoid a particular dealer, it signifies to buyers the drug’s potential potency. “If it does kill somebody they run down the road and get more,” he explained. The DEA alluded to a similar phenomenon in its 2017 National Drug Threat Assessment. According to the federal government’s leading drug agency, public health warnings intended to notify “the community that a particular heroin stamp is known to contain fentanyl” can actually cause “some users to go in search of it.” Still, the DEA believes that the vast majority of heroin users who are exposed to fentanyl actually have no desire to take the drug.

Beyond the supply-side economics of drug addiction outlined by the DEA, we spoke to folks in Sullivan County about what they believed was driving the epidemic. Surprisingly, their answers didn’t revolve around drug cartels in Mexico or the profits to be made by selling fentanyl. Instead, their responses were rooted in the small, rural community in which they lived. In fact, the only person to mention illegal drug markets in Mexico or China was a county-level official who told us that the federal government was failing in its responsibility to stop drugs at the border. In describing the federal government’s “lackluster response” to the opioid epidemic, he pointed out that opioids — unlike marijuana — cannot be grown legally in the United States. “The great poppy fields of Sullivan County aren’t fueling this issue,” he reassured us. Still, the vast majority of people we spoke to talked less about foreign drug markets than about the realities of why people in rural communities turn to opioids in the first place.

“If you were to drive over Route 52 to go to ShopRite, it’s not uncommon — if you keep your eyes open — to see people walking over that overpass with a baby carriage, holding the baby in their arms, with everything they own in the carriage.… Now put it this way. I’m going to be brutally honest with you. If I was in that position, I’d probably shoot dope too. I would boot up and bang off in a heartbeat if I felt that hopeless.”

From a Bird’s-Eye View to a Worm’s-Eye View: Pathways to Addiction in Sullivan County

Although we spoke to a variety of people in the fields of public health, law enforcement, and even families struggling with addiction, they pointed us in the direction of three main pathways to addiction — legitimate injuries, recreational use, and self-medication.

Legitimate Injuries

When asked about the different pathways to addiction, several people told us that friends and family members were prescribed opiates following a physical injury at school or work — for example, a high school student who was prescribed painkillers after suffering a football injury; a young woman who had her wisdom teeth removed; or a middle-aged man who slipped and fell at work. Because men and women of all ages are susceptible to these types of injuries, the sentiment in Sullivan County is that opioid addiction “does not discriminate” — that it threatens young and old, rich and poor, urban and rural communities alike. However, some respondents, many of them public health officials, expressed concern that middle-aged people and the elderly are at a particularly high risk for opioid abuse. “It’s not just young people,” one official told us. “A lot of people think that it’s the eighteen-to-twenty-four-year-olds. What we’re really finding is it’s predominantly more in the thirty-and-forty-year-olds.”

National statistics bear these findings out. Between 1999 and 2014, the CDC found that prescription overdose rates were highest among people aged twenty-five to fifty-four years old. Listening to the folks in Sullivan County, many people feel that prescribing practices themselves obscure the dangers of taking prescription medications to manage pain-related injuries. In the paraphrased words of one respondent — it starts off with a prescription, then leads to a problem. It’s not cocaine, which you buy from the street. It’s not marijuana, which comes from an illegal source. The rationalization is that it’s from a doctor. People don’t realize its impact.… Once you’re hooked, you’re hooked.

Recreational Use

Despite growing concern over opioid abuse among middle-aged Americans, there was considerable speculation regarding the pathways to addiction among those who use drugs recreationally. Oftentimes, though not always, these discussions focused on teenagers who are allegedly stealing painkillers from their parents’ medicine cabinets. According to Aleta Lymon, former director of prevention and training at the old Recovery Center in Monticello, young people are gaining access to prescription drugs by going to pharm parties in Sullivan County. “They’re taking the medicine from their medicine cabinets at home, and they’re going to parties, and they’re dumping all these meds into bowls,” she told the Times Herald Record. After talking with several people about opioid abuse in Sullivan County, such concerns appear rooted in the belief that drugs have increasingly come to define youth culture in the United States. Thus, one parent and community organizer told us about songs like “Rockstar,” which glamorize “poppin’ pillies” and other forms of drug use. Kids, she explained, are looking for more ways than ever to get high, whether that’s by huffing glue or mixing prescription cough syrup with soda and Jolly Ranchers (the so-called purple drank or sizzurp, named after the ingredient used to make it). Still, the notion that kids are doing what they’ve always been doing, namely partying with drugs to have fun, was prevalent in many of the conversations we had about young people. While it remains to be seen whether, and to what extent, changes in American youth culture precipitated the current opioid crisis, one thing is certain — the drugs available to young people are becoming both increasingly deadly and available.

Self-Medication

While pill parties and the purple drank conjure up images of teens acting irresponsibly and out of control, it is clear that young people turn to opioids for other reasons. Of the three women we spoke with whose children struggled or are struggling with addiction, two indicated that their daughters were ostracized at school because they didn’t fit in. The use of heroin among these young women was not a form of acting out, or even the result of a dependency on painkillers. Instead, it was a form of self-medication. According to one parent:”My daughter she was bullied in school and I think that’s part of the reason why she started.” For others, opioids helped their children cope with anxiety, depression, and other co-occurring mental health disorders. Thus, another parent indicated that her daughter, now in recovery, was never prescribed painkillers. In fact, she never even smoked cigarettes. Yet once her daughter discovered that marijuana could help reduce her anxiety, it was only a matter of time before she started using alcohol, and eventually heroin, to cope with her mental health issues. This is not to say that all people with mental health disorders use drugs to self-medicate their symptoms, or vice versa. Indeed, the causal relationship between mental health and substance abuse disorders is still unclear. However, the number of people with co-occurring disorders is significant. In 2016, an estimated 8.2 million adults aged eighteen or older (3.4 percent of all adults) experienced co-occurring mental health and substance abuse disorders, even though only about half received either mental health care or substance abuse treatment (NSDUH 2017).

Research on the rising morbidity and mortality of middle-aged white Americans indicates that teenagers are not alone in using opioids to self-medicate. In a now-famous study, researchers Anne Case and Angus Deaton found a surprising increase in midlife mortality among non-Hispanic whites living in the United States due to drug overdoses, suicides, and chronic liver diseases. In interpreting their data, Case and Deaton have argued that these so-called “deaths of despair” may be linked to declining wages, limited job opportunities, and fewer marriages. In other words, failure to fulfill societal expectations has led to higher rates of suicide, drug abuse, and other risky behaviors, particularly among middle-aged white Americans. In Sullivan County, which is 73 percent white, the effects of joblessness and other “collateral issues,” as they were described to us, can be seen driving through town. As one service provider described it:

If you were to drive over Route 52 to go to ShopRite, it’s not uncommon — if you keep your eyes open — to see people walking over that overpass with a baby carriage, holding the baby in their arms, with everything they own in the carriage.… Now put it this way. I’m going to be brutally honest with you. If I was in that position, I’d probably shoot dope too. I would boot up and bang off in a heartbeat if I felt that hopeless.

In Sullivan County, like many other rural communities throughout the United States, townspeople have watched as industries died, wages diminished, and jobs evaporated. Yet many people remain. In this setting, people don’t just abuse drugs because they want to experiment or have fun, although some of them do. In this setting, people depend on drugs to numb the reality of an otherwise painful existence. Absent an understanding of how these broader, socioeconomic forces feed into the cycle of addiction, any response to the opioid crisis will be inadequate at best.

Conclusion

Sullivan County isn’t much different from other communities ravaged by the opioid epidemic. An increasing number of people are dying but there’s very little anybody can do to stop it, or at least that’s what most people told us. Thus, when researchers, journalists, and politicians ask the question about how opioids became a problem, it is imperative that we speak to the people who face down this epidemic every day in their communities. Indeed, a national narrative that begins and ends with pharmaceutical companies and aggregate data misses the human element of addiction and the multitude of pathways to get there.

Follow the series and join the conversation with the hashtag #StoriesfromSullivan.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Katie Zuber is the assistant director for policy and research at the Rockefeller Institute of Government

Patricia Strach is director for policy and research at the Rockefeller Institute of Government

READ THE SERIES

The Rockefeller Institute’s Stories from Sullivan series combines aggregate data analysis with on-the-ground research in affected communities to provide insight into what the opioid problem looks like, how communities respond, and what kinds of policies have the best chances of making a difference. Follow along here and on social media with the hashtag #StoriesfromSullivan.