Neil Gorsuch is poised for confirmation as an associate justice of the United States Supreme Court, where he will fill the seat vacated by Antonin Scalia more than a year ago. The debate over his confirmation has been bitter and contentious for two reasons. One, concerning his judicial philosophy, follows a pattern we have seen more often than not recently. With a closely divided Court operating in an ideologically charged environment, senators and the public are curious about how he is likely to vote as a member of the Court. The other is a unique controversy over whether any nomination made by President Trump is legitimate in the wake of the Senate Republicans’ unwillingness to consider President Obama’s nomination of Merrick Garland for the same seat.

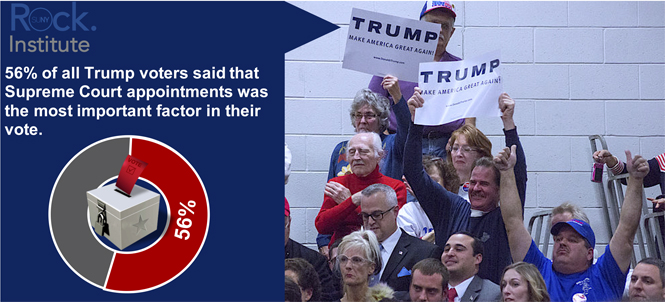

The heat of the struggle, however, is driven by the same underlying concern. There is an uncharacteristically large gulf between the right and left wings of the Court on controversial political issues (think of abortion, campaign financing, the role of religion in public life, racial discrimination, and gender identity issues, to name only a few) and the justices on the right and the left are relatively even numerically. What happens with Scalia’s seat is thus of great political importance. The successful appointment of Neil Gorsuch will preserve the conservative coalition on the Court and creates the groundwork for growing conservative dominance should President Trump succeed in adding more justices. The public’s recognition of this showed in the exit polls from the 2016 election. Usually, the president’s authority to appoint justices to the Supreme Court ranks very low, if at all, as a campaign issue, but in 2016, 69 percent of all voters thought that Supreme Court appointments were an important factor in their vote, and 56 percent of Trump supporters said it was the most important factor![1]

All of this underlines an insight from the world of political science. The federal courts, as institutions, are both political and legal. They are legal because of their special institutional role in interpreting law, which places boundaries around how they conduct work with significant political implications. As only one example, observe how federal judges appointed by both Democrats and Republicans have thwarted some of President Trump’s actions, including his two attempts to limit travel by Muslims. But they are political as well, as the decisions they reach can contribute to supporting political regimes. This is particularly important because of the length of time that justices (and federal judges) serve — while the historical average is about 16 years, four of the current members of the Court (Anthony Kennedy, Clarence Thomas, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, and Stephen Breyer) have been associate justices for more than 20 years. While justices’ political commitments do at times shift over their years of service, the recent spate of ideological struggles over nominations has led to the confirmation of justices who tend to hew more to a particular set of political commitments, and who appear to be strongly in favor of either maintaining the New Deal institutional order or dismantling it.

Should President Trump get a chance to nominate additional justices to the Court, a big question will be whether a conservative Court will be satisfied to advance conservative constitutional projects, like the reinvigoration of economic liberties, the bolstering of free religious exercise, and the limiting of other kinds of liberty and equality agendas. President Trump and his advisors will hope for this, of course, but they will likely also want a Court specifically invested in shoring up the president’s political authority. This may be considerably tougher to achieve. While a Court may tilt in a liberal or conservative direction, most Courts in U.S. history have maintained a commitment to the independent power and authority of the Court itself, regardless of the ideological or partisan landscape. Thus, even though a Court with more than one Trump nominee will move the law in conservative directions, it is unlikely to stay on the sidelines if it believes that the president’s actions cross lines defined by the Court’s role as the ultimate legal interpreter, or those inherent in separation of powers.

Julie Novkov is a professor of political science and women’s, gender, and sexuality studies, and currently serves as the president of the Western Political Science Association. She is the author of three books, including the prize-winning Racial Union: Law, Intimacy, and the White State in Alabama, 1865-1954, and co-editor of three volumes, as well as many articles and book chapters on subordinated identity and political development in American constitutional law.

[1] CNN Election 2016 Exit Polls, Updated November 23, 2016, http://www.cnn.com/election/results/exit-polls.