Rockefeller Institute of Government President’s Note:

Every 20 years, New Yorkers have the chance to vote on whether to hold a constitutional convention (known as a ConCon). The next vote will be held this November. If the voters approve a convention, delegates will be elected in November 2018, and the convention will open in April 2019. As the vote approaches, the Rockefeller Institute will continue to provide New Yorkers with information in various forms: public education sessions, publications, and debates. Please follow on Twitter or sign up on our website for all the latest information.

Today’s piece, by David Siracuse, is one of a series by pro- and anti-ConCon experts. We hope the dialogue provides insight to help inform voters come November.

Proponents of the constitutional convention (ConCon) have argued in this forum about its benefits, particularly that it is needed to enact comprehensive ethics reform separate from the legislature. However, many organizations are opposed to the convention. Several weeks ago more than 100 organizations across the political spectrum came out against holding a ConCon. Many of the organizations are among the most powerful interest groups in the state.

Why are these groups opposed to convening a ConCon? The basic premise is the risk is not worth any potential reward. Below is a summary of the players and reasons behind their opposition.

The Opposition

Opposition comes from the political Left, Center, and Right including the AFL-CIO; NYSUT; environmental groups; the State Rifle and Pistol Association; Republican NY Senate Majority Leader John Flanagan; Democratic Assembly Speaker Carl Heastie; the Independent Democratic Conference (a group of conservative Democrats in the NY Senate); and a lobbyist group (Empire Government Strategies) led by Jerry Kremer and Anthony Figliola, who wrote a book (with Maria Donovan) called Patronage, Waste, and Favoritism — A Dark History of Constitutional Conventions. To highlight the strange bedfellows another way, Planned Parenthood has joined Right to Life and the Working Families Party has joined the Conservative Party of NY in opposition to the convention. A full list of groups that have joined the anti-ConCon coalition called New Yorkers Against Corruption (NYAC) can be found here. These groups and individuals make many of the same arguments about cost, outside money, unnecessity, and New Yorkers’ rights.

Opponents Argue a ConCon Would be Dominated by Special Interests Who Would Drive the Convention and Its Outcomes

At its core, the groups argue that the process would be structured in such a way as to make it less a “people’s convention” and more of an “insider’s convention” meant to eliminate various rights because outside money could dominate the delegate selection process and, subsequently, the convention.

Candidates, for instance, running to be delegates wouldn’t be subject to normal campaign finance laws. J.H. Snider, a constitutional convention scholar — while an advocate of constitutional conventions in general — notes that contributions made during the last 19 days before a referendum election are exempt from disclosure laws. The article describing these loopholes is available here. Campaign finance rules fuel many groups’ concerns that the process could be dominated by “political insiders” because big money would dominate the process

State ConCons are generally low-information affairs. Even though holding a ConCon was supported by 62 percent of New Yorkers, the most recent Siena poll found that two-thirds of voters hadn’t even heard of it. J.H. Snider notes that “…better-organized and well-financed interest group information campaigns can be especially persuasive.”

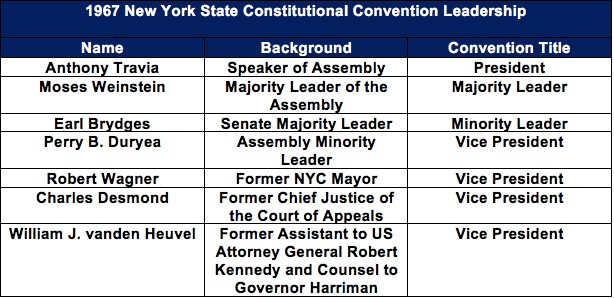

Not only are opponents concerned about undue outside moneyed interests, they believe it would be wasteful because conventions have been dominated by elected officials, especially from the state legislature. Constitutional scholars have argued that ConCons should aim to be as independent as possible from the legislature. Snider explains it best, stating “Conventions whose membership overlaps with that of the legislature may more aptly be described as special sessions of the legislature than conventions.” The governor recently reiterated his concern about a convention being made up of elected officials, and it is something he’s argued against since his 2010 campaign. Snider says, “Labeling them conventions, however, may have procedural benefits for legislative leaders, such as smaller majorities required for constitutional amendments submitted to voters, double-dipping in salary as both a legislator and a delegate, and exemptions from ethical safeguards that apply to legislators but not to delegates (depending on how the legislature drafts the enabling act for the convention).” In fact, the 1967 ConCon was headed by then-current Assembly Speaker Anthony J. Travia and virtually the entire state legislative leadership from both the Assembly and Senate.

Currently there is no law in New York that would prevent current legislators from running for a delegate position, and a recent set of proposals to do so by Assemblyman Brian Kolb (R – AD 131) was summarily dismissed during this year’s legislative session. For thoughtful counterarguments on who exactly we consider “insiders” and why we should value their expertise, see a Rockefeller Institute blog post by Peter Galie and Christopher Bopst here.

The “Special Interest” Convention: Loss of Constitutional Rights and Significant Taxpayer Cost

Opponents argue that a convention dominated by “special interests” would put essential rights in the constitution at risk. On the Left, labor groups worry that worker rights would be at risk, such as the right to collectively bargain; the prohibition against pension reductions; worker compensation guarantees; and a provision for social welfare of the needy. Independent Democratic Conference Member Diane Savino speaks to potential setbacks to worker rights, noting, “Whether it’s repealing pension protection for workers, whether it is repealing prevailing wage laws, whether it’s repealing collective bargaining rights, in a post-Citizens United world, none of us can feel safe about a constitutional convention.” Keeping these protections in place has been the rallying cry of large membership networks, and they note other recent setbacks such as Wisconsin’s Act 10 in 2011 that, among other things, limited unions from negotiating on anything other than wage increases based on cost-of-living adjustments.

If a ConCon is approved, the opposition groups worry that these sections of the constitution would not be included in the new version and would invalidate provisions that they spent many years fighting for.

At the same time that more liberal groups are concerned with opening up a “Pandora’s Box” to more conservative legislation, conservative groups have the same concern in reverse. For example, gun control measures could be codified, making them more permanent than the current SAFE Act. Timing is also important. As delegates would be selected in 2018 (a gubernatorial election year), the typically higher turnout could favor Democrats and lead to more liberal constitutional measures. Although the control of the legislature was split between Republicans (controlled the Senate) and Democrats (controlled the Assembly) in 1967, more Democrats were elected as delegates. The potential for more Democratic delegates heightens the conservative group opposition to a ConCon. As a counterpoint, however, it has been noted that the way delegates are currently selected — three per Senate district, and 15 at-large — would help the Republicans since the districts are gerrymandered in their favor.

Environmental groups have also come out against the ConCon. One particular element of the constitution, the “forever wild” provision (Article XIV) for New York’s Forest Preserve lands, does as it states — protects forests from being tampered with. One vocal group, the Adirondack Mountain Club, notes that allowing the constitutional convention the potential to change the “forever wild” clause could only be worse than what is already on the books. Another general concern is the current national political climate. Environmentalists are apprehensive that much of the Trump administration’s antienvironmental rhetoric could influence the New York ConCon agenda.

Some opponents state that a ConCon would not only be dangerous, it would be costly. Estimates for it — including salaries, staff, and organization — run anywhere between $47 and $108 million. A $350 million price tag was being bandied about, but that number was the result of the 1967 convention cost ($10-$15 million) being mistakenly inflated twice, as was pointed out by Gerald Benjamin. See the potential convention cost estimates discussed here. Mike Long, the chairman of the Conservative Party of New York said, “It is important for voters to understand that the history of holding constitutional conventions proves they are a colossal waste of taxpayers’ money that fails to accomplish what supporters claim.” Former Assemblyman Arthur “Jerry” Kremer and Anthony Figliola said, for example, that “The reality is that the convention process in New York has been, for the most part, an expensive, time-consuming production that offers little in terms of accomplishment.” Whatever the cost, the opponents argue that this money could be spent on more pressing issues.

A Better Way: The Current Amendment Process Through the Legislature

Opposed groups also note that it would be unnecessary, as changes could be enacted through the normal amendment process in what would amount to legislators “just doing their job.” Senate Majority Leader Flanagan has been on record stating that the current constitutional amendment mechanism is satisfactory. Anti-ConCon groups frequently cite the fact that the New York constitution has been amended over 200 times in the past 100 years as proof of this fact. The constitutional amendment process in New York requires changes to pass two separately elected legislatures (in other words, passed once before and once after a November election) and then approved by voters. Per Ballotpedia, the state legislature referred 19 constitutional amendments to the ballot in recent history (1996 through 2016). Voters approved 15 and rejected four of the referred amendments. In fact, voters will decide on two new constitutional amendments this year alone. The 2017 November election will present voters with the option of stripping pensions from public officials who have been convicted of a felony in relation to their official duties. In short, opponents find that a ConCon would be an unnecessary expenditure and there is a viable alternative to enacting change already in place.

Moving Forward and Other Subjects of Contention

Other issues also make it to this political battle, such as whether stronger/weaker reproductive rights would be considered and whether the state would legalize recreational use of marijuana. Other areas of reform include the court systems, the relationship between state and local government, and ethics. For a more detailed discussion of these, see the Rockefeller Institute blog post written by Galie and Bopst here.

With five months until the 2017 elections, heavy persuasion and mobilization efforts by both proponents and opponents to the ConCon have yet to be seen. As it comes closer to the election date, it will be important to keep a pulse on what messages various groups are pushing and what resonates with the public in what should be a typically low turnout off-year election.