Repealing and replacing Obamacare is a top priority of the Trump administration and Congress, and there has been extensive coverage of proposed replacement bills and their potential effects on costs and access. However, as President Trump noted during the early discussions on a replacement bill, “…it’s an unbelievably complex subject. Nobody knew health care could be so complicated.” Many Americans are familiar with visible provisions such as health insurance exchanges, insurance coverage mandates, and the Medicaid expansion. However, the Affordable Care Act also supports several demonstration projects to improve health care costs, access, and quality, but that are not well-understood by the public.

One such program is the Financial Alignment Initiative, which aims to improve the coordination of care for individuals enrolled in both Medicare and Medicaid, and align financial incentives between the two public insurance programs. As Medicare has a higher reimbursement, providers have an incentive to bill more services to Medicare. If it works as intended, the initiative may improve health care quality and outcomes, and contain costs. It is one of several demonstration programs included in the Affordable Care Act to test innovative solutions to persistent problems within the health care system.

The Financial Alignment Initiative encourages states to provide better quality health care more efficiently to Americans who are dually enrolled in Medicare and Medicaid. These “dual eligibles” are a diverse population with extensive health care needs. While Medicare provides coverage for the elderly and people with long-term disabilities, Medicaid provides health care for low-income people and select other populations such as individuals receiving Supplemental Security Income and qualified pregnant women and children. Dual eligibles are typically vulnerable persons, such as elderly people who “spend down” their assets to qualify for long-term care under Medicaid and blind or disabled Medicaid enrollees. Many dual eligibles have multiple chronic conditions and incur high medical costs, representing one-third of Medicaid and Medicare expenditures.

A desired outcome of care coordination is to manage costs for dual eligibles with complex health care needs, while at the same time improving its quality.[1] Such coordination may include assessing an individual’s medical, physical, and social support needs; creating a personalized plan of care; sharing information across providers; and providing “patient navigators” to help individuals access the services they need. Coordination also involves reconciling differences between Medicaid and Medicare regulations and treatment guidelines where they affect the health care of dual eligibles.

Medicare typically reimburses providers at a higher rate, so providers treating dual eligibles have financial incentives to shift costs to Medicare to maximize their revenue. For example, dual eligibles who reside in nursing homes are often unnecessarily transferred to hospitals because Medicare pays for acute care but not for nursing homes. Another care coordination challenge is developing robust and interoperable electronic health records to enable the sharing of clinical information across multiple providers through health information exchange. Limited information sharing can drive costs up considerably if duplicate procedures are performed or inappropriate treatment threatens patient safety.

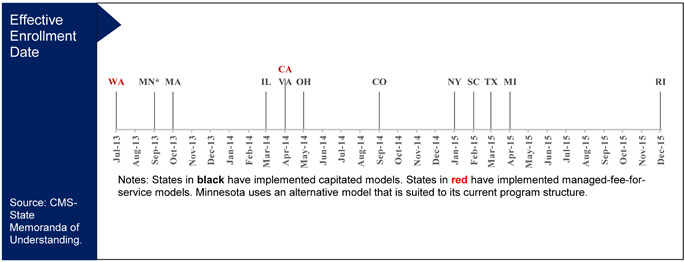

To improve care coordination for dual eligibles, the Affordable Care Act included funding for the Financial Alignment Demonstration. Since 2011, 12 states have worked with the federal agency that oversees the demonstrations — the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) — to implement one of two models.[2] States collaborate with CMS to select and tailor a model, depending on the structure of their existing Medicaid program.

Ten states have implemented capitated models, which are three-way contracts between the state, CMS, and health plans. These plans receive fixed rates to treat each dually eligible patient regardless of the number of services, with funding contributed by both CMS and the state. Under these states’ Financial Alignment Incentive programs, there are new financial incentives to improve quality and reduce costs. In the capitated model, both the Medicare and Medicaid programs withhold some of Medicare-Medicaid plans’ revenue; the two programs then pay out these withheld amounts depending on quality improvements.

Two states have implemented managed fee-for-service models, which are two-way contracts between the state and CMS. Providers in these states continue to charge on a per-service basis, and they are reimbursed by CMS for Medicare services and by the state for Medicaid services. Minnesota uses an alternative model that is suited to its current program structure, in which only the administrative (but not financial) functions are aligned.

Twelve States Have Adopted Federal Alignment Incentive Programs

As of December 2015, 371,358 beneficiaries have been enrolled in the capitated demonstration in nine states.[3] Each state is required to have its demonstration evaluated by an external contractor. Early evaluations from CMS show that the Financial Alignment Demonstration integrates Medicare and Medicaid systems, increases enrollment rates, and improves care coordination.[4]

The first main finding from the CMS evaluations to date is that instead of navigating two separate systems of care, beneficiaries can receive appropriate care under one integrated system with common policies and procedures in the capitated model. It took longer than state officials expected to align these systems. However, the Medicare-Medicaid plans — private health plans designed to provide integrated and coordinated benefits for dual eligibles — have devoted considerable efforts to activities such as hiring management and data analytics staff, building data collection and record systems, creating materials and websites for members, and incorporating new reporting and compliance requirements.

Second, plan enrollments increased, despite starting later than expected. In general, it can be challenging to encourage beneficiaries to switch plans due to barriers such as limited skills in navigating our complex health care system and unclear messaging about the benefits of switching to a different plan. Many states overcame these barriers by establishing “passive enrollment” procedures, in which beneficiaries were automatically enrolled in the new plans unless they opted out. This reduced the burden on beneficiaries to understand the new plans and how to make the transition.

Third, states dedicated staff time for outreach to key stakeholders in order to improve care coordination. Although there is no quantitative empirical data documenting changes, the early evaluation reports present multiple anecdotal evidences of success. For example, the Massachusetts program evaluation described how a care coordinator connected a member to Meals on Wheels for nutritional support, a local medical provider, phone services, and a visiting nurse. All of these services were important for this member to receive holistic health care and wrap-around social support services. Several states also provide training programs for care coordinators regarding their roles and responsibilities, and strategies to work with clients. However, the lack of trained care coordinators remained as a challenge.

Despite these early successes, the CMS evaluations report that many stakeholders are concerned about beneficiary safeguards and protections for a variety of reasons. For example, passive enrollment into the demonstration may reduce beneficiaries’ awareness and choice. In addition, beneficiaries may not be able to receive existing services due to the transition. Many of the states in the Financial Alignment Incentive program developed beneficiary safeguards and protections, such as advance enrollment notification; continuity of care provision; and ombudsman programs that include outreach, advocacy, complaint resolution, and options counseling. However, there has only been limited evidence to date on the effectiveness of these safeguards.

Overall, the CMS evaluations indicate that Financial Alignment Incentive has had several important successes in integrating Medicare and Medicaid systems and improving care coordination. Although there has been limited evidence on beneficiaries’ safeguards and protections and improvements in reducing costs, demonstration programs such as these can test novel approaches to improving the efficiency of our health care system and the quality of care. Different types of demonstrations are implemented across states, reflecting their unique health care policy environments. An important direction is to identify the successes and challenges across the types of models. Further external research is also needed to confirm findings and understand casual mechanisms using additional data and analytic approaches. For example, although the CMS evaluation reports identify passive enrollment as one of several reasons for increased program uptake, a recent academic study found that many passively enrolled beneficiaries opted out or disenrolled from the Medicare-Medicaid plans. As “repeal and replace” debates continue, it is important to not simply monitor the proposed changes to the visible aspects of Obamacare, but also to track provisions that enable government agencies to evaluate alternative approaches to improving cost, access, and quality outcomes.

[1] Although cost management is one desired outcome from care coordination, many studies show that it does not successfully decrease total costs due to increased administrative support, such as managing systems, outreach to target populations, and monitoring.

[2] Minnesota is working with the CMS to implement demonstrations outside of these two models.

[3] The earliest effective enrollment date for Rhode Island is December 2015, so this estimate only includes nine states.

[4] These evaluation reports were developed by an external contractor to CMS.