Over the last four years, the Trump administration has explicitly worked to deregulate, reorganize, and remake the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). President Biden’s new administration has signaled it will reverse course on some of the Trump administration’s policies and guidance that have limited the regulatory powers of the EPA. While a candidate, President Biden outlined a number of ambitious climate and environmental goals—ones that are not commensurate with the current state of the EPA and its regulatory policies and practices. The Biden administration’s goals include, but are not limited to: achieving 100 percent clean energy and net-zero emissions by 2050; decarbonizing the electricity sector by 2035; establishing new methane pollution limits for the oil and gas sector; conserving 30 percent of US lands and oceans by 2030; ensuring clean and safe drinking water through infrastructure investments, polluter enforcement actions, accelerating research, and implementing enforceable standards; ensuring new infrastructure reduces climate impacts and pollution; and, investing $1.7 trillion over 10 years in clean energy and environmental justice.

To achieve most of these goals, among other actions, the Biden administration will need to reverse regulatory and administrative changes implemented at the EPA (along with other key agencies) under the Trump administration and address longer-term challenges that the agency is facing. To that end, President Biden nominated Michael Regan, secretary of the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality, as the new EPA Administrator. Regan’s confirmation hearing by the US Senate was on February 3rd, 2021, and senators on the Environment and Public Works Committee voted on the 9th to advance his nomination to the full Senate.

Among the challenges the new administrator will face are longer-term declines in funding and staffing incommensurate to the agency’s mission, more recent targeted cuts and staffing changes, and the rollback or revision of over 100 environmental regulations over the last four years. This post will consider the state of the EPA and what issues the new administration will need to address as it seeks to revitalize the agency in order to accomplish the new administration’s goals and “build back better.”

Budget and Staffing Trends

The EPA has seen significant declines in funding over the last several decades. Although the agency’s budget has generally increased in real dollars since it was established in 1970, its adjusted (2012) value has decreased by roughly 50 percent since its peak in the early 1980s. In 2020, the EPA’s funding was just over 10 percent higher than the agency’s initial budget in 1970 (in adjusted dollars; see Figure 1). Likewise, the EPA’s staffing levels have fallen roughly 22 percent to just over 14,000 since its peak in 1999, and is now at the lowest staffing level since 1989 (see Figure 2). This is despite the passage and implementation of several significant programs that the agency has been charged with administering since its inception, including landmark legislation, such as: the Safe Drinking Water Act (1974); the Resources Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) and Toxic Substances Control Act (1976); the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA) or the Superfund Program (1980); hazardous and solid waste amendments to RCRA (1984); Executive Order 12898 making environmental justice part of the agency’s mission (1994), and others.

Figure 1. Federal and EPA Budgets: 1970-2018 (Index 2000=100)

SOURCE: US Environmental Protection Agency and The White House.

Figure 2. Federal and EPA Workforce Growth: 1970-2018 (Index 2000=100)

SOURCE: US Environmental Protection Agency and The White House.

While this is a longer—if uneven—trend, staffing declines, targeted budget cuts, and reorganization under the Trump administration have been of particular note as part of a broader strategy to deconstruct the “administrative state” across all agencies and the explicit goals of environmental deregulation, streamlining compliance, and reducing business and administrative costs. While the EPA has avoided the most severe budget cut proposals under the Trump administration, its resources have been disproportionately affected compared to many agencies over the last few years. In 2017, the administration established a buyout program (through the Voluntary Early Retirement Authority and Voluntary Separation Incentive Payments) to support staffing cuts at the EPA. In total, 372 staff accepted the 2017 buyouts. While the plurality of these positions were based in Washington, DC, regional agency staffing was also impacted—if unevenly, when considering earlier reported staffing levels. Region 3—based out of Philadelphia—was impacted the most, as 40 staff members accepted buyouts. Region 2, which includes New York State, comparatively lost seven staff members.

EPA and Federal Staffing, 2015-19

| Agency or Federal (combined) | Staff Type | Sept '15 | Sept '16 | Sept '17 | Sept '18 | Sept '19 | # Change in Staff | % Change in Staff |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPA | STEM | 9,442 | 9,590 | 9,322 | 8,972 | 8,762 | -680 | -7.20% |

| Federal | STEM | 324,377 | 329,957 | 330,683 | 331,938 | 337,993 | 13,616 | 4.20% |

| EPA | Agency Total | 15,445 | 15,634 | 15,098 | 14,457 | 14,291 | -1,154 | -7.47% |

| Federal | Total | 2,071,716 | 2,097,038 | 2,087,747 | 2,100,802 | 2,132,812 | 61,096 | 2.95% |

SOURCE: “Federal Workforce Data,” FedScope, US Office of Personnel Management, accessed February 2, 2021.

From 2015 to 2019, the EPA lost 1,154 full-time equivalent (FTE) staff members in total, a loss of 7.47 percent. At the same time, the overall staffing levels at federal agencies grew by 2.95 percent. Of the loss of staff at the EPA, the majority—59 percent or 680 FTE—were science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) professionals. Interpreting the agency’s staffing levels are partially complicated by the EPA’s Senior Environmental Employment (SEE) program. This decades old program employs workers over 55 years-old, including EPA retirees, to supplement the work of full-time agency staff. The workers hired through the program each year are not considered federal employees or employees of grantee organizations according to the EPA’s Office of Inspector General (OIG) and are compensated at a lower pay scale. This workforce has also diminished in recent years, from 1,111 workers in 2015 to 831 in 2019—a more than a 25 percent decrease.

Such shifts in funding and staffing under presidential administrations and changes in Congressional leadership while significant are not without precedent. Similar cuts occurred under the Reagan administration, for example, when the EPA’s operating budget fell by 27 percent from 1980 to 1983. Likewise, budget cuts occurred under the Obama administration as the EPA’s budget decreased 23 percent between 2010 and 2013. Though the Obama administration later sought to restore some of that funding, Republican majorities in both houses of Congress at the time held the agency’s budget flat or further decreased it. Similarly, although the Trump administration proposed enormous budget cuts to the EPA each year, the Democratically held House and the Republican held Senate at the time rejected those cuts. Given the already historically low budget and the agency’s expanding responsibilities over time, however, continuing to hold the budget relatively flat has resulted in a decreased capacity to fulfill its duties.

Shifts in staffing, particularly with respect to more senior positions and leadership at the EPA, have also raised concerns about an increased revolving door with industry—as former regulators are hired as industry lobbyists and industry lobbyists are hired or appointed as regulators. As with budget cuts, this issue is not new to the EPA or federal agencies more broadly, but the visibility and impact of the revolving door under the Trump administration at the EPA was more pronounced than most. For example, the most recent agency administrator, Andrew Wheeler, after starting his career in public service as a special assistant in the EPA’s toxics office and working at the US Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works, spent years as an industry lobbyist for coal, uranium, and chemical industry interests (among others) before heading the EPA. Likewise, Kelley Raymond, a senior adviser in the EPA’s Office of Air and Radiation under the Trump administration, previously worked as an industry lobbyist contesting federal regulations on hydrofluorocarbons (refrigerants that are greenhouse gases), working to delay the 2015 ground-level ozone standard, and limiting the use of scientific studies in rulemaking.

Superfund

The Superfund program was established in the wake of the industrial contamination of Love Canal (a neighborhood in Niagara Falls, New York) and the environmental justice movement that grew alongside it. The program works to remediate the most contaminated sites in the country. The Superfund allows the EPA to require responsible parties to cleanup or reimburse the agency for cleaning up the site, but in many cases no responsible party may be determined. When there’s no responsible party identified or the responsible party is bankrupt, the Superfund Trust Fund was created to pay for the cleanup and the cost of administering the program.

The decreased capacity of EPA resources and staffing are reflected in the backlog of Superfund sites waiting for cleanup funding, which totaled 34 sites in 2020, a 15-year high. At the same time, Superfund cleanups slowed to a 30-year low. Addressing this lack of funding for and enforcement of the Superfund program is salient to the Biden administration’s stated environmental justice and climate goals. These goals sought to “target resources in a way that is consistent with prioritization of environmental and climate justice,” in recognizing that “communities of color and low-income communities have faced disproportionate harm from climate change and environmental contaminants for decades.”

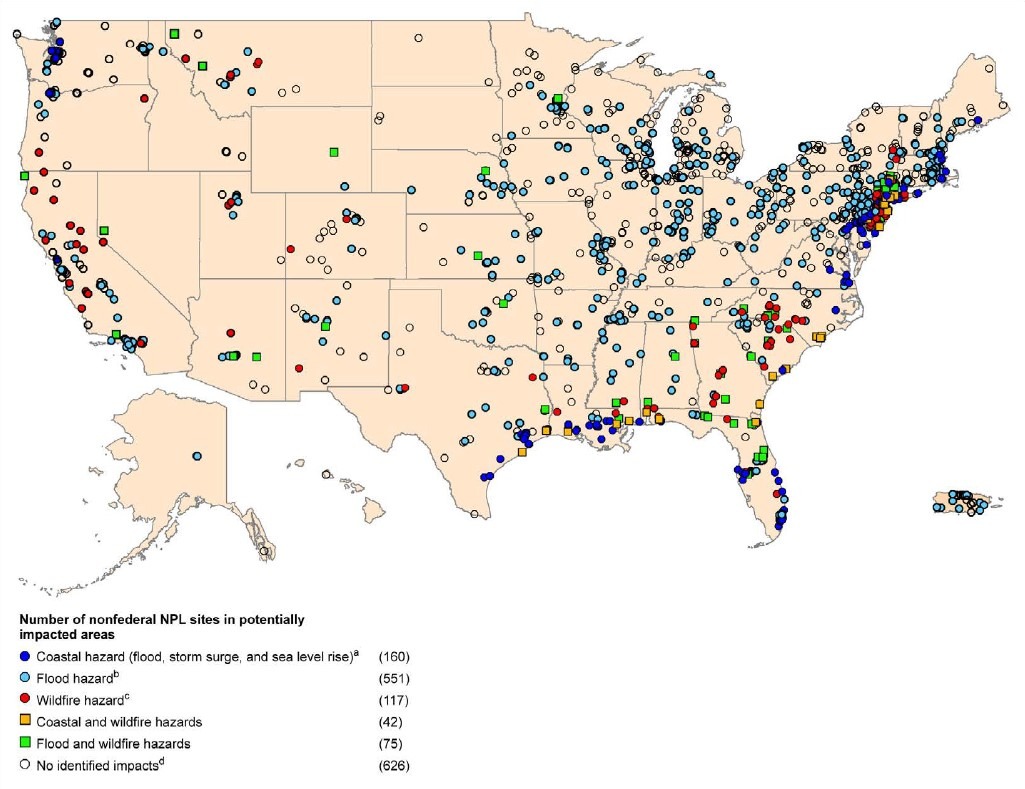

Unfortunately, poor communities and Black, Indigenous, and people of color tend to be disproportionately impacted by environmental burdens, including toxic and hazardous waste. While the Superfund was established in direct response to the environmental justice movement, research has also reflected that such communities may still be underrepresented in the Superfund program. In addition, due to the often layered or intersecting nature of those environmental burdens, Superfund sites are likely to be further impacted by climate change, magnifying the hazards such sites present. A 2019 report by the Government Accountability Office (GAO) found that out of the approximately 1,571 nonfederal sites listed on the National Priorities List (NPL) for Superfund, roughly 60 percent (945) were at additional risk due to one or more climate change effects.

While the program’s Trust Fund was initially based on the “polluter pays principle” and funded through a set of fees, namely on chemicals and petroleum, these fees were not reauthorized by Congress in 1995—and therefore expired. The cost for the program has therefore shifted from being industry-supported to being taxpayer-supported over the last 25 years. To that end, the Biden administration could work with Congress to reauthorize or restructure the fees supporting the Trust Fund based on the polluter pays the principle to ensure that the agency has the resources to fulfill this part of its mission and to advance the administration’s climate and environmental justice goals.

Figure 3. EPA’s Nonfederal NPL Sites in Areas That May Be Impacted by Flooding, Storm Surge, Wildfire, or Sea Level Rise

SOURCES: US GAO analyses of EPA, Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA), and US Forest Service data,GAO-20-73, https://www.gao.gov/assets/710/702158.pdf.

Rolling Back the Rollbacks

Reinstating commensurate and historic funding and staffing levels at the EPA is not only necessary to ensure the agency’s ability to enforce existing environmental laws and regulations, but to begin the work of restoring and enforcing those which have been rolled back or revised during the Trump administration. These rollbacks and revisions have reflected the administration’s broader deregulatory and deconstructive aims with respect to the administrative state, and raised concerns about the extent of the EPA’s “regulatory capture” over the last four years.

In total, the Trump administration has worked to reverse or revise over 100 environmental rules. These include protections that worked to decrease greenhouse gas emissions and mitigate climate change, as well as environmental standards and requirements that will be salient to achieving the Biden administration’s goals. Perhaps foremost among those rules that the Biden administration will need to reverse the rollback of in order to achieve its climate and environmental goals are:

The Clean Power Plan (CPP)

The CPP was established under the Obama administration to cut emissions from coal and natural gas power plants, which in 2019 made up 98 percent of the electric power sector’s 1,618 million metric tons of carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions (60 percent and 38 percent respectively). In 2018, the electricity sector was the second largest source of greenhouse gas emissions, inclusive of methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O) emissions, according to the EPA. The Trump administration elected to replace the CPP with the much narrower Affordable Clean Energy (ACE) Rule in 2019, which has (like the CPP) been challenged by state Attorneys General. ACE’s climate impact has been found to be minimal by some researchers with others demonstrating its potential to increase emissions. Given that the goal of the original CPP—to cut carbon emissions from the power sector by 32 percent below 2005 levels by 2030—was nearly reached in 2017 at 27 percent (though emissions increased the following year) any reinstatement of the CPP or a newer rule would likely seek to strengthen those goals.

The Methane Rule(s)

The Trump administration amended or rescinded a handful of regulations related to methane emissions from the oil and gas industry (as well as others), aimed at decreasing the cost of compliance for industry actors. Methane as a greenhouse gas is 28 times more potent than CO2 in terms of its climate impact (over a 100-year period). While naturally occurring, most methane emission (about 60 percent) come from human sources. One of the most significant human sources of methane is fossil fuel production, generally second only to the agricultural sector, though the scale of oil and gas related emissions may still be significantly underestimated. The changes to methane regulations by the Trump administration included:

- rescinding the requirement that oil and gas companies to report methane emissions;

- revising/partly repealing the rule limiting methane emissions on public land;

- rescinding the requirement that oil and gas companies detect and repair methane leaks; and,

- in addition to those methane rules related to oil and gas, the Trump administration revised or rescinded other methane rules, including an extension to the timeline for state and federal plans to cut methane emissions from landfills.

The Waters of The United States (WOTUS)

The Trump administration revised the definition of WOTUS under the Clean Water Act (CWA) of 1972, with the stated intent of lowering the cost of compliance and establishing regulatory certainty. WOTUS is a term used to define those bodies of water subject to the CWA, which protects those waters from the discharge of pollutants. The new rule implemented by the Trump administration worked to narrow the definition of WOTUS, explicitly excluding a dozen categories of water bodies. This leaves states to take up permitting and oversight work in the absence of federal protections, though most states do not have a complimentary permitting program already established. According to Attorneys General in states filing suits against the new rule, the new definition excludes roughly half of all wetlands and 15 percent of streams in the country from protections. The impact of these exclusions was furthered by a subsequent rule issued in January of 2021 that increases the threshold for damage under expediated CWA permitting processes related to 10 types of permits (including mining, agriculture, and commercial or residential development).

Fuel Economy Standards

The Trump administration revised the fuel economy standards set under the Obama administration in 2012, decreasing the annual improvements required and lowering the goal from achieving 54.5 miles per gallon by 2025 (for new passenger vehicles and light trucks), to just around 40 miles per gallon by 2026. The original standards were estimated by the EPA to decrease greenhouse gas emissions by 900 million metric tons, use 1.8 billion barrels less of oil, and save drivers $2,800 in fuel costs over the lifetime of their vehicle. Automakers took different approaches in response to the revised standards. Some supported the new lower standards, while others reached voluntary agreements with California—which is able to set its own standards and maintained the standards implemented in 2012. It is unclear what precise standards President Biden will commit to, but he has more broadly stated his commitment to “developing rigorous new fuel economy standards aimed at ensuring 100 percent of new sales for light- and medium-duty vehicles will be zero emissions and annual improvements for heavy duty vehicles.”

The Social Cost of Carbon

The Trump administration rolled back the Obama administration’s methodology for the social cost of carbon and replaced it with a new rule that valued the social cost at a much lower rate. The social cost of carbon represents a monetary estimate of the economic impact from a given unit of greenhouse gas emissions. It is one important way in which future potential impacts or averted impacts are given weight in the rulemaking process with respect to climate policy. The Obama administration established the first federal valuation of the social cost of carbon in 2016 at around $50 per ton of CO2. This was replaced by the Trump administration’s valuation ranging from $1 to $7. This valuation is important to broader climate and environmental rulemaking. Since the early 1980s, beginning with Executive Order 12291 by President Reagan, major federal rulemaking has generally been required to consider cost-benefit analysis. This type of analysis has not always included externalities and has inherent difficultly valuing certain costs and benefits with respect to environmental health—for example, those future oriented, those involving ongoing scientific study of impacts, and those difficult to quantify. New climate and environmental rules—like those included in President Biden’s goals—would be more difficult to demonstrate as having a positive cost-benefit analysis using a lower social cost of carbon value, and therein faces challenges to their implementation.

- A related rule, issued by the Trump administration on December 9, 2020, further separated the consideration of more direct benefits from those indirect benefits—including the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions. Unless they are rolled back, these rules make it challenging to justify new federal climate rules using cost-benefit analysis. They effectively discount their longer-term benefits on climate relative to more immediate financial costs.

The Exclusion of Science

In 2018, the EPA released a draft rule limiting which studies could be used in federal rulemaking which was finalized in January of 2020. The rule was framed by the Trump administration with respect to creating more “transparency in regulatory science.” In effect, the rule restricts studies used in federal rulemaking to those with publicly available data, leaving many significant and relevant medical, public health, and environmental health studies outside of consideration. The reason such studies do not always publicly disclose data is largely because they include personal identifying information that is connected to other sensitive data—such as personal medical data. Due to research ethics, medical confidentiality, and legality, such data should not and cannot be made public. Nonetheless, it is necessary for measuring and understanding the impact of environmental harms. The quintessential example of such studies is the Harvard Six Cities Study. First published in 1993, the large-scale study examined the impact of particulate matter on mortality—finding an (linear) increased risk of mortality with long-term exposure to PM2.5 (a certain level of particulate matter). Many other longitudinal and large cohort studies have since been published confirming this finding. Consequently, these studies acted as the basis for new federal environmental rules to improve air quality. Such work has been deemed by the Trump administration and several industry interests over the years as “secret science.”

- The impacts of this kind of restriction on science were reflected in recent actions by the EPA, as the lack of publicly available data was cited by the agency in rejecting or giving less weight to studies linking the pesticide chlorpyrifos to human health impacts. This dismissal underpinned the agency’s analysis that the science was ‘inconclusive’ despite evidence of impacts related to prenatal exposures.

- Very recently, on February 1, 2021, the US District Court of Montana granted a request by the EPA under the Biden administration to vacate the rule. The request was made on the basis that the EPA under the Trump administration had made the rule effective immediately, without waiting the required 30-days after publication for substantive rules. The request was granted, averting the need for the current administration to undo the rule through more lengthy rulemaking processes.

Other concerns have been raised with regard to the review of new rules by staff in the Office of Management and Budget (OMB). The OMB’s Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) centralizes the final review of rules under the Executive Office of the President before agency rulemaking can be made public. Recent reports, for example, reflect that the OMB under the Trump administration worked to weaken new EPA guidance on the importation of products contain perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS)—though the editing of guidance documents goes beyond the office’s usual purview in rulemaking. Recently, the Biden administration has issued a memorandum to review and make recommendations on the OMB’s process of regulatory review.

Some congressional offices have also noted that the recent finalization of a number of these rules and rollbacks mean that they could be subject to the Congressional Review Act (CRA)—just as the Biden administration begins and Democrats now hold a (slim) majority in the Senate, in addition to their existing majority in the House of Representatives. Under the CRA, Congress has a certain amount of time following an agency’s issuance of an interim final rule or final rule (and some guidance documents) to overturn that rule. The CRA further provides that a joint resolution cannot be filibustered in the Senate and, therefore, only needs a simple majority vote.

Conclusions

In order to achieve the ambitious climate and environmental goals that President Biden has outlined, the administration will need to begin rebuilding the Environmental Protection Agency. This includes addressing long-term budget cuts so that the agency has the resources to carry out its historically expanding mission as well as the new goals of the administration. Additionally, funding must be reestablished for programs like the Superfund on the polluter pays principle. If the agency is to do this work, it will also need to replace many of the thousands of staff positions that have been lost over the last few decades—including those more recent losses of STEM professionals—in order to ensure it has the capacity to carry out the research, administration, and enforcement of environmental rules.

Alongside rebuilding agency capacity, the EPA will need to begin to unravel the dozens of environmental rules that have been rolled back under the Trump administration, effectively expanding the work in front of them as they go. Revising many of these rules will undoubtedly take time and further resources given established regulatory processes and the likelihood that many of them will be contested through the court system before being implemented. Though some of the rules may be more quickly addressed through the Congressional Review Act, this makes it all the more important that the administration prioritize rules that will ease the process for further environmental protections to be implemented—like those related to the inclusion of relevant science in rulemaking and the social cost of carbon. Both increased capacity and rulemaking are necessary to achieving the administration’s stated climate and environmental goals. The Rockefeller Institute will continue to monitor any budgetary, staffing, and rule changes as they unfold.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Laura Rabinow is deputy director of research at the Rockefeller Institute of Government