An Afro-Cuban American scholar, Amalia Dache is an assistant professor in the Higher Education Division at the University of Pennsylvania. Her experiences as a Cuban refugee and student traversing US educational systems—among them urban K–12 schools, community college, state college, and a private research-intensive university—inform her research and professional activities. Dr. Dache was a Richard P. Nathan Public Policy Fellow at the Rockefeller Institute and conducted research related to how racial and economic factors inhibit local postsecondary education in the Finger Lakes region of New York.

Introduction

I grew-up in the Finger Lakes region of Upstate New York in a working-class Black and Latino neighborhood of Rochester—the city where Frederick Douglass created the publication The Liberator in 1831 and the region where Harriet Tubman lived and worked to help roughly 300 enslaved people reach freedom through the Underground Railroad in the 1850’s. Monroe County, one of nine counties in the Finger Lakes Region, is the most racially diverse county in the region. This is due in part to the city of Rochester, its influx of southern Black residents in the late 19th and early 20th century, and its Puerto Rican and Latino immigrant history in the early 20th century. However, the remnants of racial segregation have been filtered over time through the city’s changing landscape, housing structures, and the location of economic and educational resources, leaving a residue.

Rochester is the most densely populated city in the Finger Lakes Region, with the highest number of postsecondary institutions. However, you might not know by looking at Rochester that some of the city’s colleges and universities follow a historical trajectory of geographic movement and racial/ethnic demographic change. Institutions such as Rochester Institute of Technology, University of Rochester, Monroe Community College, Nazareth College, and St. John Fisher College were originally founded in central areas of the city, but eventually moved to the southern suburban periphery as the city racially diversified.

Racial college access geographies are an area of research that I began working in while studying for my PhD in educational leadership at the University of Rochester in 2014. My ongoing research addresses an important facet of the broader discussion on education deserts—areas with either no colleges or universities or limited to only a community college nearby. This literature, however, has not explored local (county, city) and historical contexts of college accessibility for diverse residents and the racial/ethnic composition of higher education institutions. As such, research on racial college access geographies helps address an existing gap in the literature, which is national in scope, yet not municipally specific nor inclusive of private and for-profit institutions in analyses.

In this blog post, I introduce the Integrated Spatial-Racial College Access (ISRCA) map, which builds on my earlier work, and shares some initial analytical mapping from ISRCA. The map is used to illustrate the spatial-racial variability of college access in the Finger Lakes Region. In doing so, I further explore the relationships between race, economic-status, and proximity for residents and their area colleges and universities. Results reveal that there are inequities of urban and rural proximity across race, class, and county lines, and outlines what might be needed to more adequately analyze such inequities in access across more rural areas.

Why My Geography Mattered

Rochester was my home for most of my young and adult life, from 1981 to 2014. My family of six lived in several rented homes in the northeast quadrant of Rochester. Northeast Rochester had the highest concentrations of the Latino, Black, and working-class residents. We had ourselves immigrated to Rochester in 1980 as Mariel Refugees through a refugee relocation program. My mother was a machine operator for Nu-Kote International—a factory that made typewriter ribbons on Ridgeway Avenue in an industrial section of northwest Rochester. My father was a neighborhood mechanic.

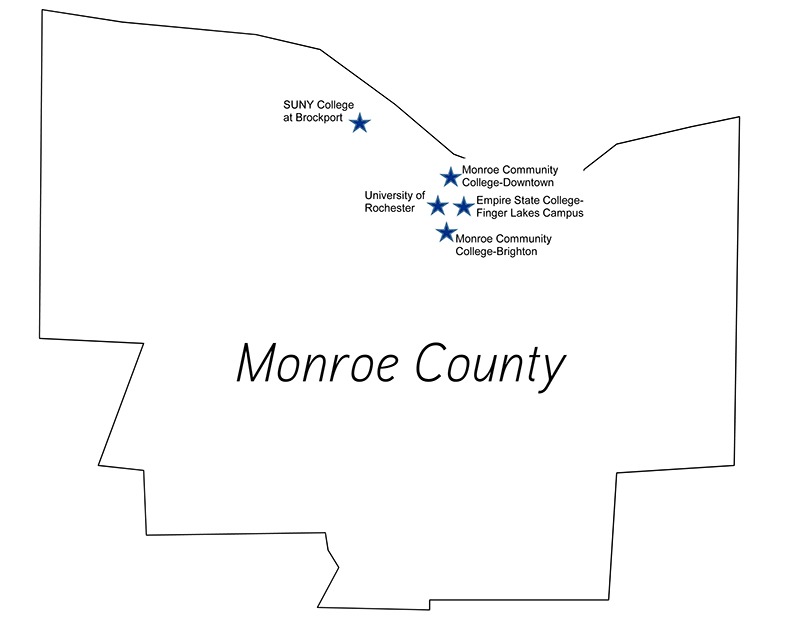

My parents eventually bought a home in the northeast and I attended primary and secondary schools in the Rochester City School District (RCSD), then college at Monroe Community College, taking courses at both the downtown campus and the main Brighton campus. I transferred after four years to SUNY Brockport College and studied English literature to prepare for what I thought would be a career in law as an attorney. Instead, I fell in love with the intellectual life of my professors and decided to pursue the professoriate. I went on to earn a master’s in liberal studies at SUNY Empire State College and a PhD at the University of Rochester with a focus on higher education and college access. Although I attended diverse institutions, there was one common denominator: all of them were in Monroe County.

I didn’t realize how much space and place mattered in my local educational journey until I began to unpack my primary educational experiences attending three different elementary schools in the RCSD: Martin Luther King School No. 9 (for kindergarten); John James Audubon School No. 33 (for 1st grade); and, Martin B. Anderson School No. 1 school (for 2nd-6th grade). What I learned as a student in the RCSD is that I was a part of racial desegregation efforts through busing, to turn a predominantly white, middle-class/upper-class school into a more racially-diverse school, via raising the Black, Latino, low-income local student enrollments.

As a kid, I didn’t understand why I was bused along with several of the kids in my northeast neighborhood to attend Martin B. Anderson’s School No. 1 in the southeast part of Rochester, but I am glad I attended it. School No. 1 was in the part of the city that had the wealthiest residents and was predominantly white. Yet the school was only two miles from my home. I lived off of Main Street—if you head just one and a half miles south, you enter the wealthier historic district of the city, but if you head one mile north you enter blighted areas of the city. School No. 1 served a deaf population and I learned how to sign as part of our primary school curriculum. The school was very diverse. I had two Black principals while I was there, one Black teacher in 2nd grade, and one Latina Spanish teacher. Teachers with Italian-American surnames were common as well, which made them easier for my parents to pronounce. Integration matters.

What Analyses of Race and Space Can Tell Us About Postsecondary Education Access in Monroe County

My dissertation project in 2014 explored local college access for Monroe County residents. That research included the collection and analysis of observational data from riding buses in northeast Rochester and collecting census tract data obtained through a Geographic Information System (GIS). The major findings from my research were the presence of both a college desert and a college oasis between the city and surrounding suburban areas. When I compared the southeast suburbs of Monroe County to Rochester, I found discrepancies in the number of college institutions and the types of institutions in each area. That is, I found “a college desert” in the city and a college oasis in the suburbs.

A college oasis has more colleges and greater diversity of college options (read: two-year, four-year, private, and public) when compared to a college desert. The economic characteristics of Monroe County residents reveals disparities in income and employment distribution. Most employed professionals reside in the suburbs, while residents with highest rates of unemployment reside within city limits. The city of Rochester, a college desert, has the highest concentrations of residents in the county with less than a high school diploma, and the highest concentrations of residents above 25 years of age with less than a 9th grade education. Although Rochester residents have the highest needs for educational attainment and economic mobility, they have far fewer colleges in close proximity (within five miles) when compared to their suburban “college oasis” counterpart.

Nationally, research on public higher education access and “education deserts” states that roughly 10 percent of the US population lives in such deserts. Yet, missing in the national analyses of education deserts is a local focus of college access, which includes diverse institutional types (i.e., private, public, not-for-profit and for-profit). Analyzing demographics as they relate to proximity in the Finger Lake Region’s colleges and universities, you will find that there are race and income disparities in access for rural as well as urban residents.

An Integrated Spatial-Racial College Access (ISRCA) Map of the Finger Lakes Region

US higher education is funded largely at the state level and through student tuition dollars. The role of cities and counties in directly funding higher education is present in their support of community colleges. Municipalities also make indirect investments through the development of transportation systems critical for local resident’s access to postsecondary institutions. The ISRCA (Integrated Spatial-Racial College Access) map helps make visible some of those investments by allowing users to analyze local college accessibility, through educational attainment and college enrollment factors, while exploring residential racial and socioeconomic status demographics at the neighborhood level.

When using the ISRCA map, you can click on variables of interest that you would like to visualize on the map. For example, in Monroe County, the census tract where SUNY Brockport College is located (my alma mater) has a 9 percent Black population and the college has an 11 percent Black student enrollment. The three public postsecondary institutions in Monroe County have Black student enrollment ranging from 11 to 16 percent. This is somewhat in line with the county’s Black population share of 16.2 percent. Monroe Community College’s downtown campus is located in the city center with the darker blue census tracts indicating higher Black population.

Figure 1. Public Higher Education Institutions in Monroe County

Figure 2. Private Higher Education Institutions in Monroe County

The private colleges in Monroe County are located on the edges of the city. They have Black student enrollment ranging from 4 to 19 percent. The only private school with Black enrollment higher than 10 percent is the one for-profit institution. None of the schools are located in a census tract with a black population share of greater than 10 percent. Private not-for-profit institutions in the county could therefore improve their enrollment of local Black students in the region.

Spatial College Access Mapping in Rural Communities: The Greater Finger Lakes Region

IRSCA builds on my work in Monroe County by applying the college oasis and desert framework to a larger geography: the greater Finger Lakes region. The Finger Lakes region includes nine counties surrounding Rochester (Monroe County). The areas surrounding Rochester are significantly more rural than Rochester. All but one of the eight counties outside of Monroe has more people living in a rural community than an urban center. As with the urban centers, rural residents also face challenges when accessing higher education with fewer colleges in proximity and socioeconomic barriers. Monroe’s surrounding eight counties were served by only six institutions. When building an access map for more rural geographies, I identified three challenges in understanding rural access to college.

| Percent of County Population Living in a Rural Setting | Number of Main Campuses | Number of Branches | |

| Monroe | 6.4% | 12 | 6 |

| Genesee | 59.9% | 1 | 0 |

| Livingston | 54.6% | 1 | 2 |

| Ontario | 47.5% | 3 | 5 |

| Orleans | 60.9% | 0 | 2 |

| Seneca | 58.7% | 0 | 0 |

| Wayne | 60.7% | 0 | 1 |

| Wyoming | 64.1% | 0 | 2 |

| Yates | 71.2% | 1 | 0 |

1) Differences In Population Demographics

This form of mapping emerged out of a city context that is racially diverse. Rural communities like those in the greater Finger Lakes region are more racially homogenous. Still, the mapping analysis can be a valuable tool for understanding the relationship between demographics like socioeconomic class and college access. To better understand the relationship between socioeconomic factors and access to college, a tab was added that codes census tracts based on poverty level (share of people with household income below 200 percent poverty level) and educational attainment (share of population with a bachelor’s degree). Low-income and first-generation students are underrepresented in colleges and universities across the country. Developing a model that centers on these economically marginalized students could help visualize spatial factors of proximity and access. Each higher education institution is represented by a marker whose scale represents the share of students receiving financial aid. The availability of financial aid will be a critical determinant for low-income students deciding on college.

2) Prevalence of and Data for Branch Campuses

Outside of Rochester, the Finger Lakes region is served by two community colleges: Genesee and Finger Lakes. These schools operate with a hub and spoke model; each has one main campus and multiple branch campuses. Some of these branches are strategically placed in the service area to improve access for more remote students. They offer courses across a range of subject areas and academic support services. Other branch campuses house specialty programs such as viticulture (the cultivation of grapevines) or environmental conservation. Of the eight counties in the Finger Lakes (excluding Monroe), only four are home to the main campus of a college. Three of the four remaining counties are serviced only by the branch campuses of community colleges.

A limitation to understanding the role branch campuses play is data. Publicly available institutional enrollment data does not have separate statistics for branch and main campuses. They share an aggregate number for enrollment demographics regardless of location. This means that researchers and policymakers do not have current information on the number and profiles of students served by each location. This is a major implication of this study that could better assist policymakers and local educators in the region to address their local population’s educational attainment needs.

3) Understanding Access Challenges in Rural Communities

In urban communities, where many students are dependent on public transportation and proximity more greatly correlates to access, locating colleges in the suburbs presents a challenge to these students. Rural residents are, however, more dependent on cars and rarely have access to public transportation. More information is required to better understand the relationship between proximity and enrollment for rural residents.

The past year accelerated the long-standing trend toward online education. Students in more rural locations already had limited access to remote courses offered by public and private colleges. Remote learning was previously a helpful feature that allowed geographic and schedule flexibility and it quickly became a necessity for all students in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. As remote learning becomes a more significant part of higher education, it has the potential of improving access for students who are not conveniently located near an institution. Theoretically, it could eliminate the spatial access issues that lead to college deserts. But the opportunity for remote education is only available to those who have access to the infrastructure required. Broadband access in many rural communities is unreliable and cost prohibitive.

Further research is required to better understand the importance of in-person learning to rural students and the feasibility of remote education.

Takeaways

In reflecting back on my college access experiences in Monroe County, having a tool with which my family, neighbors, and I could have illustrated social, economic, and racial phenomena that at times were invisible or hard to point to would have been a treasure. The ISRCA map can help visualize uncharted paths for many underrepresented students as it makes visible the racial, socioeconomic, and spatial realities of our geographies and higher education institutions. It assists not only in representing the demographics of our neighborhoods, but in highlighting the potential relationships between the ability to see college as within reach, and its literal proximity.

A recent trend across state higher education systems, as in Pennsylvania, Connecticut, and Vermont for example, are proposals to consolidate. These proposals to consolidate the administrative functions at regional colleges may prove complicated for communities that are already facing limited access. Reducing the number of colleges in proximity to low-income communities and communities of color could translate to further travel for students already marginalized due to their class status and the cost of travel. While remote access may be considered a viable alternative to proximity, many of these marginalized students face alternative access issues. Policymakers and administrators must understand the way in which marginalized students engage with their local higher education institutions. This includes tracking how they interact with coursework and services remotely and at branch campuses.

It assists not only in representing the demographics of our neighborhoods, but in highlighting the potential relationships between the ability to see college as within reach, and its literal proximity.

Federal higher education policy reforms may help address underrepresented students’ presence at local colleges and universities under the Biden administration. The new administration, which has a majority in both houses of Congress, may move the needle on college affordability in the area of cost containment and financial aid. College promise programs, which are placed-based programs designed to increase higher education attainment would provide up to 100 percent tuition cost for in-state students at community and state colleges. College promise programs may not, however, address nontuition-based proximity factors within a state, but they may provide more indirect financial support for local students who have to travel longer distances to attend community colleges on the edges of their county. As policymakers at the local, state, and federal levels develop programs designed to improve access to higher education, mapping tools such as the ISRCA can be helpful in identifying the place based challenges underrepresented students face.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Amalia Dache is a Richard P. Nathan public policy fellow at the Rockefeller Institute of Government.