Even the best statistics cannot adequately convey the problems associated with drug overdose deaths or the policy solutions most suited to addressing them. We talked with Nabarun Dasgupta, an epidemiologist at the University of North Carolina’s Injury Research Prevention Center and the Opioid Data Lab, about the importance of learning from lived experience and the improved research and policy that comes as a result.

Dasgupta describes his work as “telling stories about health with numbers.” Like many epidemiologists, he studies opioid use and misuse from a population perspective, that is, how opioids affect groups generally. But population studies are not the sum total of the work he is involved with. In fact, the Opioid Data Lab has three suites of studies: (1) large epidemiological studies using aggregate healthcare data and potentially new statistical methods; (2) medical and pharmacy practice studies that look at what is being prescribed, dispensed and how; and (3) studies that draw on the lived-experience of pain patients and people who use drugs.

It’s the third category—drawing on lived experiences—that offers a different perspective in policy research and a different set of policy conclusions. We summarize our conversation about it here. This interview is one in a series of snapshots about what the epidemic in a pandemic looks like across the country.

Why is lived experience so important in research?

Dasgupta believes that researchers can rely either on preconceived ideas about what questions are important and what explanations make sense of data or humility, acknowledging that they do not have all of the answers. It’s easy for research to fall into “tyranny of the molecule”—believing that the science of drugs themselves is enough to explain phenomena—and to ignore the human side of drug use. But he believes that incorporating lived experience can improve research.

For example, health experts have a growing concern about the presence of stimulants mixed with opioids, which can be a particularly lethal combination. There are two possible explanations for this particular mix: the drugs may have been mixed accidentally or they were intentionally combined.

It’s easy for research to fall into “tyranny of the molecule”—believing that the science of drugs themselves is enough to explain phenomena—and to ignore the human side of drug use.

Creating the proper public health response depends on knowing whether drugs were unintentionally contaminated by suppliers or whether they were intentionally mixed together by either suppliers or users and whether users know what they are taking. Mortality data can only show that there is an increasing use of this deadly combination. It does not show how or why.

Interviews with drug users, though, tell a more specific story. Because the available opioids are so powerful and strong, drug users did not want to lose consciousness right away. They wanted to be awake for the experience. Although this particular mix of opioids and stimulants may be new, combining drugs for this purpose is not. Drug users in the past similarly mixed opioids (a depressant) and cocaine (a stimulant) to create “speedballs.”

Talking to people who use drugs can provide a new way of understanding existing data and help shape effective public policy interventions.

What happened in North Carolina with the opioid epidemic?

Dasgupta says that prior to the pandemic, North Carolina had a decline in prescription opioids and overdose deaths, much like the national picture. There were some fluctuations in illicit street-drug markets—fentanyl, diacetylmorphine, and heroin—but it was relatively stable.

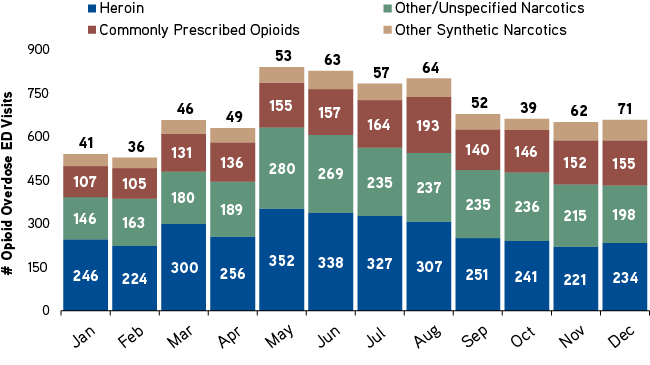

When the pandemic first hit in March, drug use in North Carolina declined. But by May, the state’s data showed an increase in emergency department overdose visits and overdose deaths, which have since declined to baseline levels. North Carolina has a relatively advanced data system that gathers information from the state’s emergency departments in real time, allowing researchers—like Dasgupta—to analyze drug overdoses and overdose deaths as they happen.

North Carolina Emergency Department Visits by Opioid Class, 2020

SOURCE: Statewide Opioid Overdose Surveillance ED Data (North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, March 5, 2021).

Dasgupta explains that we do not know yet why the pattern looks the way it does. Intuitively, we can speculate that people were at home, economic stressors hit, and services were hard to access. But we don’t know for sure.

What happened to the opioid epidemic when the pandemic hit?

In the immediate aftermath of the pandemic, federal regulations allowed methadone facilities to increase take-home dosages. Methadone is heavily regulated, and most people who start methadone maintenance must come to a federally-designated opioid treatment facility six days a week. Dasgupta explains that in North Carolina, clients forgo medication when clinics are closed on the seventh day. Stable clients who, prior to the pandemic, had a three-day take home dosage might increase to a seven-day take home dosage during the pandemic.

Dasgupta describes the longer take-home dosages as a different paradigm. Prior to the pandemic, a seven-day take-home dosage was considered a reward for good behavior and it made patients’ lives easier (daily appointments at an opioid treatment program can be burdensome). Since COVID, take-home dosages increased out of necessity. How did patients respond?

With co-authors, Dasgupta surveyed 104 patients at three North Carolina opioid treatment programs to better understand the effect of longer take-home dosages. They found longer dosages were beneficial. They allowed people to deal with the effects of COVID-19 on other parts of their lives.

Longer dosages also made a difference in their opioid-use disorder treatment, decreasing uncertainty and allowing patients to receive their doses routinely. Patients who received methadone dosages daily automatically miss one day per week when the clinic is closed. But if they miss three days, they are returned to lower baseline levels that may not be effective for them. It is a constant threat and worry for patients.[1]

Longer dosages also changed how patients felt about themselves. One participant noted how frequent trips to the opioid treatment program made her feel that she was not trusted. When she was given longer dosages, she felt she graduated to the next level and didn’t want to mess that up.

Why did you do this study? And what would be helpful moving forward?

Dagupta’s study was motivated by methadone patients who wanted their experiences documented. Patients had a range of experiences, and Dasgupta and colleagues’ recently published paper quantifies the most relevant experiences. Dasgupta says that we have the opportunity to incorporate lived experience of people in pain and people who use drugs. It’s easier to do now than it was before the pandemic, because we have made so many advances in using technology. Both researchers and people who use drugs have technological competence to communicate with one another.

He believes there’s no reason why researchers and policymakers can’t include people with lived experience in their research and decision-making processes.

To learn more about Dasgupta’s study on take-home dosages see: “Take-Home Dosing Experiences among Persons Receiving Methadone Maintenance Treatment During COVID-19.”

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Patricia Strach is a fellow at the Rockefeller Institute of Government

Elizabeth Pérez-Chiqués is a fellow at the Rockefeller Institute of Government

Katie Zuber is a fellow at the Rockefeller Institute of Government

[1] Patients starting methadone treatment for opioid-use disorder are initially prescribed low doses (10-15mg) and they are assessed for their tolerance. Doses slowly increase depending on individual need, but the average effective dose is 60 to 120 mg. If they miss three consecutive doses, patients are returned to baseline. Many methadone patients fear dropping back down to 10-15mg when higher doses of methadone are effective for them.