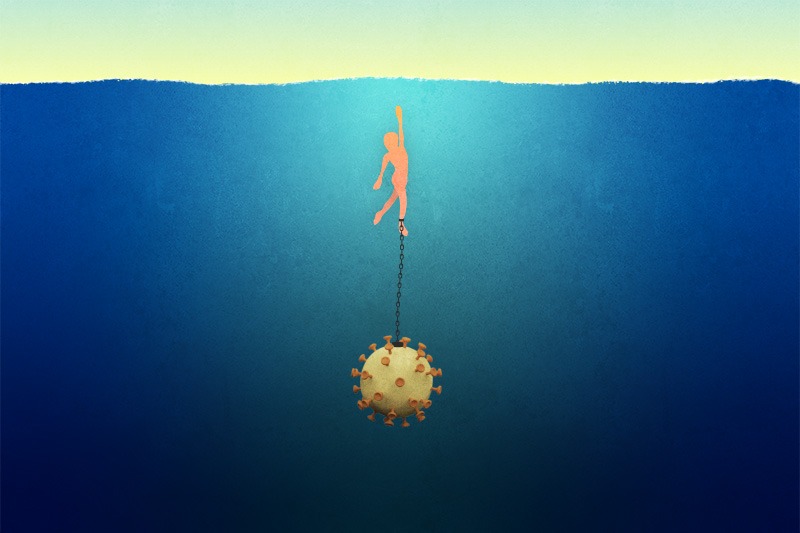

During the COVID-19 pandemic there was an unprecedented increase in overdose mortality. The pandemic worsened an overdose crisis already at record levels. This crisis was fueled increasingly by fentanyl, a cheap and extremely strong synthetic opioid, and the adulteration of other drugs, including cocaine and methamphetamine with fentanyl. The pandemic had significant effects on the level of drug use, the lethality of the drugs themselves, the way people used drugs, and the accessibility of treatment programs and harm reduction services.

Previously, we took a deep dive into the intersection of the overdose epidemic and the COVID-19 pandemic in our series “Epidemic in a Pandemic” and looked at the impact of that intersection on policy and practice in our conference on “Developing Evidence-Based Drug Policy.” We found that the pandemic created new barriers for treatment including changing the way in which people were able to access treatment medications like buprenorphine and methadone as well as the opioid overdose reversal drug naloxone. The stress and isolation associated with COVID-19 mitigation strategies led to some people using drugs more frequently, in greater doses, or in more dangerous ways including taking drugs by themselves. The interruption of the global supply chain also resulted in the strength of drugs being less predictable to the people who use them.

There were 4,965 overdose deaths in New York in 2020, which is the highest number the state has ever experienced. The CDC disaggregates overdose deaths into the categories of accident, suicide, and assault, all of which have been in the top 15 causes of death over the past 20 years. If overdose deaths are counted as a single cause of death category, they would be the eighth leading cause of death in New York above deaths from influenza and pneumonia and just below deaths from diabetes. In order to better understand these patterns in overdose mortality we have created and updated a dashboard each year using the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Mortality Multiple Cause data. In addition to the past work the Institute has done to understand and respond to the overdose epidemic, we believe there are five key takeaways about the overdose epidemic and the intersection with COVID-19 that are revealed by the CDC’s overdose mortality data.

Overdose Deaths are at an All-Time High

In 2020, the last year for complete CDC Mortality data, overdose deaths reached an all-time high increasing over 30 percent between 2019 and 2020. Unfortunately, preliminary data for 2021 shows a continuation of that pattern of rapid increase. Despite this national record in overdose deaths, not all states have been equally affected by the surge. Seven states saw slight declines from their all-time high overdose mortality rate in 2020, including: Wyoming, Utah, Oklahoma, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and South Dakota. Still, all of these states remained near record levels of overdose deaths; each state was within three overdose deaths per 100,000 residents of their highest recorded rates.

West Virginia remains the state hit hardest by the overdose epidemic. In 2020, West Virginia recorded an overdose mortality rate at the unprecedented level of 75 deaths per 100,000 residents which is nearly three times higher than the overdose mortality rate in New York State. Also notable for a high overdose mortality rate is Washington, DC, which recorded 59 overdose deaths per 100,000 residents.

(Animation move a little fast? Check out this data for yourself.)

The Overdose Epidemic Is a National Not a Regional Problem

Before the introduction and subsequent ubiquity of fentanyl and other synthetic opioids to the market around 2015, the overdose epidemic, specifically the opioid epidemic, was viewed largely as a regional epidemic affecting states with lower incomes and older, more rural populations. While overdose deaths were increasing throughout the country at the time, there was some truth to this characterization. In 2016, only two states—West Virginia and New Hampshire—had overdose mortality rates above 30 in 100,000. In 2020, all regions of the country have at least one state with an overdose mortality rate above 30 in 100,000.

Comparing the overdose mortality rate across time and states reveals that there were initially a few states that stood out for having high overdose mortality rates, but that gradually other states caught up and even surpassed some of the early outliers. While overdose deaths are still unequally distributed across geography in the US, the overdose mortality rate is increasing or remaining elevated everywhere.

Overdose Deaths Are Not an Urban or a Rural Crisis

In much the same way that the overdose epidemic was characterized as a regional problem in the early to mid-2010s, it was also often viewed as a rural problem that primarily affected those who lived in less dense counties further away from major cities. This was in direct opposition to the crack-cocaine epidemic of the 1980s and 1990s, which was viewed as a primarily urban epidemic.

Our data shows that rural counties and urban or suburban counties have strongly correlated overdose mortality rates especially within the same state. West Virginia, for example, has both the highest rural overdose mortality rate of 65 in 100,000 and the highest urban morality rate of 80 in 100,000. Like West Virginia, most states have a slightly higher overdose mortality rate in urban and suburban counties. Only California, New York, Virginia, North Carolina, Vermont, Connecticut, and Maryland have higher overdose mortality rates in rural counties and in New York and Maryland the difference is less than 1 death per 100,000 residents. Vermont is the only state where the rural overdose mortality rate is more than 10 deaths per 100,000 residents higher than the urban and suburban mortality rate. Notably, New York has a nearly identical overdose mortality rate in both rural and urban/suburban counties.

Overdose Mortality by Urbanicity

Methamphetamine and Cocaine Deaths Are Increasingly Associated with Fentanyl, but Which Stimulant Drug Dominates Depends on Geography

In previous research, we identified the adulteration of both methamphetamine and cocaine with fentanyl and other synthetic opioids as a crucial contributing factor to the overdose epidemic. Methamphetamine and cocaine are both stimulant drugs which mean that they act on the body by causing an increase in heart rate and blood flow, which results in a feeling of increased energy. Opioids—including heroin, prescription pain killers like oxycodone, and fentanyl—behave in the opposite way by slowing respiration and heart rate. An opioid overdose death results when the heart rate and respiration slows too much to support heart and brain function.

Opioid overdoses can be treated and reversed using the drug naloxone. Naloxone binds to the opioid receptors in the brain, essentially kicking out the illegal drug, and can return breathing and heart rate to normal in order to save a person’s life. There is no equivalent overdose reversal drug for stimulants. While an effort has been made to provide naloxone to opioid users, that effort has only recently extended to people who use cocaine and methamphetamine. If these drugs are contaminated with fentanyl, users can overdose on that fentanyl without knowing that they had taken it at all. Unfortunately, these users are less likely to recognize the symptoms of an opioid overdose or carry naloxone in order to reverse such an overdose.

Methamphetamine in particular has become both stronger and cheaper over the years, with its use spreading from the Southwest across the country. Cocaine, which has had a long-term hold in the Northeast has also become more common in states where it was once rare. To examine the different role that these two stimulant drugs play in the overdose epidemic, we ranked states by the percentage of their stimulant-involved deaths associated with methamphetamine. Stimulant-involved deaths in most states in the northeast are primarily led by cocaine while the rest of the country is led by methamphetamine. Only Maine and New Hampshire stick out in the Northeast with just under half of stimulant deaths in Maine and over half of New Hampshire stimulant deaths involving methamphetamine.

At the other end of the scale, all of the West and the majority of the Midwest are completely led by methamphetamine-related deaths. Six states—Idaho, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Wyoming—had no deaths related to cocaine at all in 2020, with all stimulant-related deaths associated with meth. A number of Southeast and Great Lakes states have significant numbers of both cocaine and methamphetamine-related deaths and the increase in methamphetamine deaths in these states has been relatively more recent compared to the West. The methamphetamine currently available in the US is stronger and cheaper than the homemade meth of the early 2000s. It is typically imported from Mexico and has gradually outpaced cocaine, which has a more complicated supply chain beginning with coca leaf farming. Methamphetamine, by comparison, is synthetic and generally made in Mexico from precursor chemicals.

Percentage of Stimulant-Involved Deaths Associated with Methamphetamine

Fentanyl Is the Main Contributor to the 2020 Spike in Overdose Deaths

Fentanyl is an extremely strong synthetic opioid that was originally developed to treat the most extreme types of pain including that experienced by terminal cancer patients. Fentanyl creates a similar type of high to other opioids—including heroin and prescription drugs like oxycodone—but requires a much smaller amount to do so. Due to its extreme potency, fentanyl can be easier to traffic because a much smaller volume is required to be transported compared to other opioids.

Due to its strength, however, it is also much more likely to be lethal, as tiny differences in doses can result in a fatal overdose. Fentanyl can be mixed with other opioids such as heroin to increase their potency or pressed into counterfeit prescription pills passed off as oxycodone and other prescription opioids. It can also be mixed with the stimulant drugs cocaine and methamphetamine intentionally to create a different kind of high or accidentally adulterate these other drugs because it is so potent that residue from a measuring or packing apparatus can easily get into other drugs.

Fentanyl began its rapid ascent in New York in 2015. Before 2015, fentanyl and other synthetic opioids accounted for only between 2 and 10 percent of New York overdose deaths; in 2015, that jumped to 25 percent of overdose deaths. In 2017, the highest single year increase in overdose deaths before 2020, fentanyl contributed to 60 percent of all overdose deaths and in 2020 that number jumped all the way to 76. Currently fentanyl contributes to three out of every four overdose deaths in New York accounting for 3,790 deaths in 2020.

Percentage of Overdose Deaths Attributable to Fentanyl in New York State

Conclusion

The current wave of the overdose epidemic is inherently linked to the COVID-19 pandemic and its effect on mental health and isolation, drug markets and transmission pathways, and treatment options. Prior to the more than 30 percent increase in overdose deaths recorded in 2020, the highest single-year increase was 2017 and then there was a promising leveling-off of overdose mortality rates in 2018 and 2019. Both the 2017 increase and 2020 increase were driven almost exclusively by fentanyl-related deaths. While geography continues to play a role in overdose mortality, all states are at or close to an all-time high overdose rate and those overdoses affect people living in urban, rural, and suburban areas.

While COVID-19 has complicated treatment and harm reduction strategies targeting the overdose epidemic, those policies will be crucial in reducing the current rate of overdose deaths related to fentanyl and other drugs.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Leigh Wedenoja is senior policy analyst at the Rockefeller Institute of Government