In July 2017, Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced that the Justice Department would allow federal agency forfeiture, also known as “federal adoptions” of assets seized by state and local law enforcement agencies. The practice, an expansion of civil asset forfeiture, was curtailed by the Obama administration in 2015 by then-Attorney General Eric Holder. Though civil asset forfeiture is not necessarily well-known to the public, the practice is unpopular across the political spectrum.

Civil asset forfeiture allows law enforcement officers to seize assets that they suspect, by a “preponderance of the evidence,” were involved in a crime. Unlike criminal forfeiture, where assets cannot be seized without a conviction, the person whose property is confiscated does not have to be convicted or even charged with a crime; the property, not the owner, is considered the defendant. Law enforcement is able to keep what is seized, or keeps the profits if assets are sold off. Once property is seized through civil asset forfeiture, the burden of proof is on the owner to prove its innocence by going to court. Unlike the more familiar judicial standard of innocent until proven guilty, assets seized though civil asset forfeiture are guilty until proven innocent. Civil asset forfeiture is big business; in 2014, the total annual dollar value of assets seized by federal law enforcement ($5 billion) surpassed total burglary losses ($3.5 billion).

Civil asset forfeiture has a long history, though the greatest increase in its practice coincides with the war on drugs of the 1980s. Proponents of civil asset forfeiture, such as Attorney General Sessions, argue that it “helps law enforcement defund organized crime, take back ill-gotten gains, and prevents new crimes from being committed, and it weakens the criminals and cartels.”

Items such as illegal firearms and explosives that are taken through civil asset forfeiture are unable to be used in additional criminal activity. Civil asset forfeiture is also justified as providing material support to law enforcement, as proceeds from assets seized can be used by law enforcement to fund items like new vehicles, additional training, and bulletproof vests, making up for any budget shortfalls. Opponents to civil asset forfeiture argue that it is a violation of the constitutional right to due process and that by allowing law enforcement offices to financially benefit from the practice it creates an incentive to “police for profit.” There are also concerns that many innocent people are swept up in civil asset forfeiture and that it is rife with abuses, including using the money seized for such nonessential items such as margarita machines, tickets to sporting events, election materials, and holiday parties.

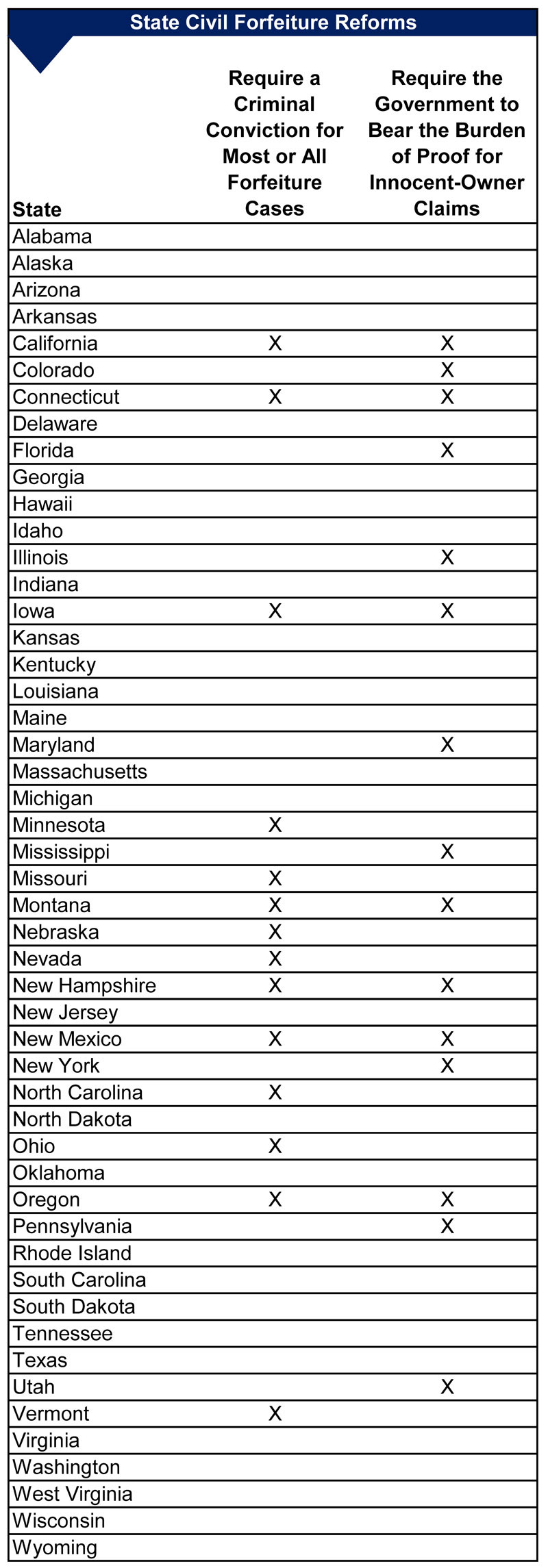

Civil asset forfeiture has always been somewhat controversial and several states have passed legislation to put limitations on its practice. Three states — North Carolina, New Mexico, and Nebraska — have abolished civil forfeiture entirely. Fourteen states (including North Carolina, New Mexico, and Nebraska) require a criminal conviction for most or all forfeiture cases. Fifteen states (including North Carolina and New Mexico) and the District of Columbia require that the government bear the burden of proof for innocent-owner claims. Other states have passed regulations that require reporting of seizures and final dispositions to state government agencies or limiting/prohibiting proceeds to law enforcement.

The federal adoptions provision that the Department of Justice reinstated, however, provides a loophole for law enforcement to get around any restrictions on civil asset forfeiture in their state. Under federal adoptions, state and local agencies can circumvent state laws on civil asset forfeiture by partnering with a federal agency to seize property that is believed to violate federal law. Up to 80 percent of the proceeds from equitable sharing is then returned to the state or local agency. Through federal adoptions, state and local law enforcement agencies are able to use the potentially more lenient federal standard of proof (“preponderance of evidence”) to seize assets that otherwise may be restricted by state statute. Marijuana dispensaries could be particularly vulnerable to being targeted through federal adoption, as the drug is classified as illegal by the federal government despite legalization in many states. The use of civil asset forfeiture and adoptive seizures, therefore, is not only an issue of civil liberties but also yet another federalism battle for the Trump administration

The Department of Justice directive to reinstate federal adoption of civil asset forfeitures may be prevented however. In September, the House of Representatives approved three amendments to a spending bill that would prohibit the Department’s ability to use funds on implementing the order. In November, a bipartisan group of senators sent a letter to the Senate Rules and Administrative Committee chairman also urging the defunding of the implementation by the Department of Justice, because “Adoptive forfeiture and equitable sharing are particularly egregious elements of civil asset forfeiture because they not only violate due process but also attack principals [sic] of federalism.”

It remains to be seen if such efforts will ultimately limit the Department of Justice’s ability to expand the use of adoptive seizures, but it has created a rare opportunity for bipartisan agreement.