This is part two of a series on “Legislating the Gig Economy.” Part One of this series addressed the legislative approach to protecting gig workers’ rights in California and other states. Part Three looks at how the COVID-19 economic crisis might influence the gig economy and labor policy going forward. See the series landing page here.

Introduction

The pandemic and the social distancing required to help mitigate the spread of the coronavirus has rapidly elevated the role of the gig economy in the United States’ larger socio-economic system. Over the past year, gig workers for companies such as Instacart and DoorDash have been on the frontlines of the COVID-19 pandemic, delivering food and groceries to those sheltering at home.

Not only are app-based platform companies designed for the new normal, surging unemployment made certain types of gig work a way for some of those laid off to help make ends meet. Such readily accessible work is likely the main reason for the nearly 13 percent increase in self-employed workers since the beginning of the pandemic. According to the latest US Census Household Pulse survey, some 15.2 million people now identify as self-employed.

Recognizing that an increasing portion of the workforce didn’t have a safety net when the recession hit, Congress temporarily extended unemployment insurance benefits to gig workers. This ultimately allowed more than 14 million self-employed individuals to collect on that benefit in 2020. To be sure, those millions likely included long-time freelancers and independent contractors such as farm laborers, musicians, or entertainment workers. But the policy focus at the time—and of this analysis—was on app-enabled employment.

The move to expand unemployment benefits to gig workers was cheered by app-based service providers like Postmates and Uber. But at the same time, those companies were also working to permanently reclassify the workers that fuel their business into a new status of employees with more limited benefits. Following a legislative defeat in California in 2019 that granted gig workers traditional labor protections, companies fought back by going straight to the voters with a ballot initiative. The proposed measure, called Proposition 22, passed in November 2020 and unwound much of California’s short-lived legislated gig worker protections.

… in California, the proposal [Prop. 22] represented an overall loss of worker benefits when compared with AB5.

That success in California may very well be replicated elsewhere and worker classification is expected to be a topic in a number of state legislatures this year. During this recession, as in previous ones, further reliance on subcontracted and gig labor over hiring full-time employees is likely to increase. Without a new employment model, the wage inequality gap that widened over the last decade could grow even broader. Companies are pursuing a limited benefits model, hoping to close the issue once and for all. But gig workers and lawmakers remain split. Some say it’s time for a new employment model that meets the needs of the modern era. But others argue that doing nothing creates a growing underclass of workers across the country that would roll back labor protections by more than a century.

Such standpoints are reflected in the National Employment Law Project’s (NELP) warning last year that “the recent coronavirus pandemic has revealed the truth: years of venture capitalist-funded growth have been fueled by artificially low labor costs that leave every single worker on these platforms at risk.” NELP noted, “their business models more closely resemble 19th century sweatshops than 21st century innovation.”

The lead up to California’s Proposition 22

The more than $200 million that Uber, Lyft, DoorDash, Instacart and Postmates spent combined in their California campaign last year received national attention. But app-based platforms have been lobbying for years in state legislatures to get similar carve-outs that protect their business model and codify their workers as independent contractors. Prior to Prop. 22, companies lobbied for so-called “marketplace platform” legislation that generally defines those who get work through app-based platforms as independent contractors. By the end of 2019, 10 states had passed legislation or changed regulations to fit this model.

To lawmakers who support such legislation, gig workers like Uber and Lyft drivers bear the responsibility for their own safety nets because they chose to work via those platforms. “The gig company exercises no control over their activities, like when or where they work, or for how long,” said Utah State Senator Curtis Bramble, who is sponsoring a marketplace platform bill in the 2021 legislative session. “No one is telling them they have to be an Uber or Lyft driver…they are making that career decision. If they choose to be independent, that also means they’re taking responsibility for [providing] their own benefits.” Advocates and workers, however, dispute this picture of autonomy.

The carve-out laws have generally been successful in Republican-led states, but hit push back in majority Democrat states like Illinois and New York. When California’s Assembly Bill 5 (AB5) went into effect in January 2020, gig companies developed a new strategy.

California’s AB5 law expanded the definition of an employee and made it harder for employers to classify workers as independent contractors. It threatened the profit model of businesses like Uber and Lyft and they, along with DoorDash, Instacart and Postmates, combined lobbying forces to develop a carve-out for themselves because they hire app-based drivers. The approach was a departure from marketplace platform bills. Proposition 22 exempts those companies from AB5, and mandated more limited worker benefits. Namely, accident insurance, a health care stipend if drivers average at least 15 active weekly hours per quarter, and a guaranteed 120% of minimum wage plus 30 cents/mile during “engaged time”—driving to a trip and fulfilling the trip.

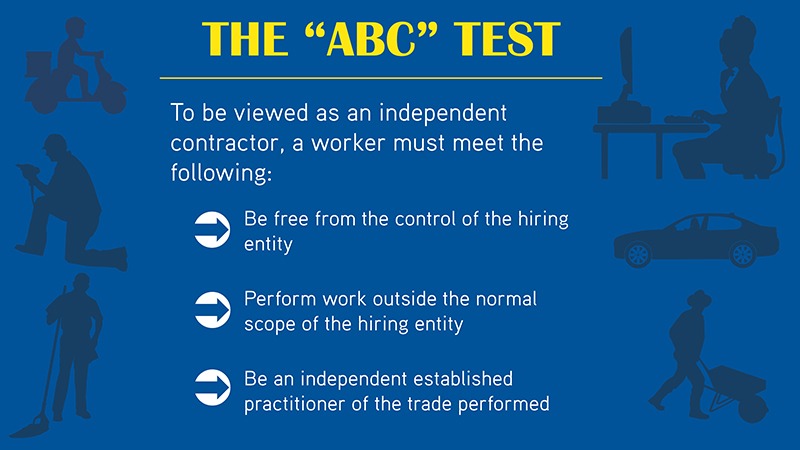

The “ABC” Test for Classifying Workers as Independent Contractors

Gig workers have protested and lobbied for some of these rights from companies for years and, in fact, Prop. 22 was similar to “portable benefits” legislation championed by domestic workers, seasonal laborers, and (more recently) gig workers. But in California, the proposal represented an overall loss of worker benefits when compared with AB5. For example, Prop. 22 took away the paid leave and unemployment benefits made available under AB5 to gig company workers who met the qualifications of an employee. That the ballot initiative was titled the “Protect App-Based Drivers and Services Act,” made this effort from companies all the more disingenuous, said NELP staff attorney Brian Chen.

Worker Benefits Under AB5 and Proposition 22

| Under AB5 and Federal Law | Under Prop. 22 | |

|---|---|---|

| Wages | Clear minimum wage; guaranteed overtime (150% of wages for work over 8 hours in one day, 40 hours in one week) | No overtime; sub-minimum wage likely |

| Expense Reimbursement | All expenses reimbursed (mileage, cell phones, car cleaning, etc.); standard IRS rate is over 57 cents per mile | Thirty cents per mile, but only mileage expenses for “engaged” miles (e.g., no reimbursement for time without package/passenger) |

| Workers’ Compensation | No-fault coverage for work-related injuries | Limited health coverage; not “no-fault;” easier for insurers to deny coverage |

| Paid Family | Leave 8 weeks of paid leave | None |

| Paid Sick Days | Three days of paid leave for illness or care of family (up to 10 in some cities); additional COVID-19 leave in some cities | None |

| Unemployment Compensation | Up to 26 weeks of cash benefits after no-fault job loss | None |

| Disability Insurance | Lifetime access to wage replacement if injured | Limited – caps total coverage for 104 weeks |

| Health Insurance | Access to federal benefits under the Affordable Care Act | Limited – calculated based on “engaged” time, reducing the benefit amount |

| Discrimination | Protection against discrimination based on a broad set of characteristics | No explicit protection against discrimination based on immigration status |

| Right to Organize and Collectively Bargain | Could be created under state law | None – and may only be afforded if state passes legislation by 7/8ths majority which is nearly impossible |

| Protection from Retaliation | Protection from termination or discipline for reporting harassment, discrimination, or wage theft | None |

| Health and Safety | Requirements put in place injury prevention plans; give workers access to sanitation facilities | No similar requirement |

SOURCE: Rigging the Gig: How Uber, Lyft, and DoorDash’s Ballot Initiative Would Put Corporations Above the Law and Steal Wages, Benefits, and Protections from California Workers (New York: National Employment Law Project, July, 2020).

Bradley Tusk, who has lobbied for Handy and other gig companies, said he believes California’s experience over the last year shows that the all-or-nothing approach of classifying gig workers as employees isn’t practical in today’s economy. A portable benefits policy on the other hand, he said, doesn’t try to categorize such workers into an outdated notion of what defines an employee. But it still subscribes to the idea that people who spend all day working and contributing to the economy have a right to a social safety net.

“Some of these labor laws on the books are from the Frances Perkins era in the 1930s,” Tusk said. “There are millions of people who participate in the gig economy one way or another and the notion that they should just be a political football [between labor unions and gig companies] is just wrong. Fundamentally you should want people to be able to pursue the jobs that make sense for them and still be able to enjoy some of the protections and benefits that employees have.”

These claims by companies and their representatives have been contested. “They’ve co-opted workers’ messaging to say, ‘We agree drivers are struggling… so here’s this so-called groundbreaking set of benefits and protections that we want to provide,’” Chen said. “This is their new model—to create a hybrid, compromise model where they seem to promise some benefits to their workers but in exchange completely foreclose upon those workers’ ability to access [other] employee benefits. And the result is a deeply exclusionary one.”

A new model for state legislation

Prop. 22 took effect in late December of 2020 and has already had ripple effects. Labor unions, some drivers and a passenger have sued, saying it violates the California constitution. However, the state supreme court declined to take up that case. The grocery chain Albertsons Companies in January laid off their unionized delivery drivers in California as a way to save money and take advantage of gig labor instead. Despite suggesting that delivery and rideshare prices would only go up if Prop. 22 didn’t pass, gig companies have now introduced additional customer fees to cover California workers’ benefits. And Grubhub workers say a change to the app’s tipping calculator now results in fewer or no tips so they are making less than before.

Meanwhile, the wide margin of victory—voters approved it 58% to 42%—has emboldened gig companies to pursue the California strategy in other places where their legislative attempts have previously been unsuccessful. “Going forward, you’ll see us more loudly advocate for new laws like Prop. 22,” Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi said during an earnings call in November.

… the wide margin of victory… has emboldened gig companies to pursue the California strategy in other places where their legislative attempts have previously been unsuccessful.

Likely candidates include New York and New Jersey, which a year ago were both considering a range of legislation mandating benefits for full-time gig workers until the pandemic and ensuing recession took center stage. In New Jersey, portable benefits legislation proposed raising consumer rates on companies who employ independent contractors to cover things like health insurance, paid time off and retirement benefits. Other legislation sponsored by Senate President Stephen Sweeney would have created an ABC test making it easier for gig workers to qualify as employees. Both of those bills are still pending in 2021.

Lawmakers in Albany this year are also (again) reportedly mulling various proposals to grant its own gig workers more benefits. But, as in New Jersey, there remains a deep divide over whether workers should be given full employee rights and privileges or a hybrid model that retains the status of at least some workers as independent contractors.

In both states, the proposals under consideration would generally expand or strengthen benefits for gig workers. But the key difference—as it was in California—is that permanently classifying these workers as independent contractors ultimately limits worker rights and benefits while also limiting the responsibilities of companies.

Even workers and their advocates are divided. For example, Chris Gerace, a New York-based rideshare driver and content creator for The Rideshare Guy (a widely read online forum by and for app-based drivers) has called Prop. 22 a step in the right direction. In fact, an anecdotal survey last year by the forum found that three-quarters of drivers say they want to remain independent contractors. Mario Cilento, president of the New York State AFL-CIO, recently said that he wants to see app-based workers receive all of the protections that employees are entitled to—but that the ABC test isn’t the only way to get there. Meanwhile, other organized groups like Gig Workers Rising and Gig Workers Collective, opposed Prop. 22 and tend to support legislation that creates a path for gig workers to be classified as employees.

New federal policy directions

The divided Congress of the past two years has had little appetite to address this particular aspect of the future of work. The federal CARES Act in 2020 did take the unprecedented step of expanding unemployment insurance to independent contractors and other gig workers, but that expansion is a temporary one. Democrats now control both houses and the executive branch—but as they are in state houses, lawmakers on Capitol Hill are divided over the best approach.

“This crisis is a chance to update our benefit and safety net systems for how people actually work (and sometimes don’t work) right now. We shouldn’t let it pass us by.”

President Joe Biden has supported classifying gig workers as employees and spoke out against Prop. 22 last year. After taking office, he immediately froze a US Department of Labor rule that would have made it easier to classify workers as independent contractors. His pick to head up the department—former Boston Mayor Marty Walsh, a staunch union advocate—also signals his intention to expand gig workers’ rights as employees.

But other top Democrats want to define gig workers as independent contractors and create a portable benefits system for them instead. “My position has simply been that a one-size-fits-all model that locks you into benefits with one employer might not work for everyone,” Senator Mark Warner, a Virginia Democrat who has sponsored portable benefits legislation, told the Washington Post in January.

The longer policymakers wait to act, the larger the likelihood that more workers will fall into this status limbo. And that is the real danger for workers, argues Alex Rosenblat, a researcher and author of the author of Uberland: How Algorithms Are Rewriting the Rules of Work. She writes in the Harvard Business Review that advocates should skip worrying that the “temporary emergency bailout of gig employers’ UI [unemployment insurance] obligations” validates the idea that gig workers should be classified as independent contractors.

Instead, she urges policymakers to seize the opportunity and momentum to enact permanent protections that combat inequality and create a better support system that works for everyone. “This crisis is a chance to update our benefit and safety net systems for how people actually work (and sometimes don’t work) right now,” she wrote. “We shouldn’t let it pass us by.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Liz Farmer is a Future of Labor Research Center fellow at the Rockefeller Institute of Government