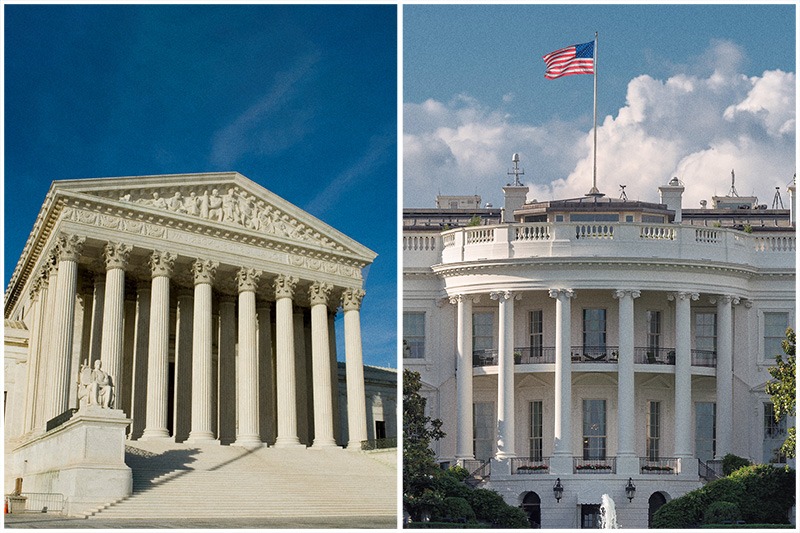

On February 28, 2023, the United States Supreme Court will hear opposing arguments on a case that is seeking to stop President Joe Biden’s plan to cancel a portion of the outstanding debt of millions of student loan borrowers. The case is a combination of two lawsuits, one that claims the Biden administration does not have the authority to enact the proposed debt relief without an enabling act of Congress, and another that the US Department of Education did not follow proper procedures for public comment. However the case is decided, the impacts on student borrowers will be substantial—and life-changing for many people.

The President’s Plan

In August 2022, President Biden announced that the US Department of Education would cancel $10,000 in outstanding debt on student loans for any borrower currently earning under $125,000 per year individually or $250,000 for married couples. For income-eligible borrowers who received a Pell Grant—federal financial aid granted to qualifying low-income students—while in college, up to $20,000 in outstanding student debt would be cancelled. This initiative is projected to provide student loan debt relief to 43 million borrowers, with the potential of eliminating outstanding loan debt entirely for an estimated 20 million borrowers.

President Biden stated that the intent of the student loan debt relief program is to provide borrowers with “a little more breathing room” as they, and the nation, recover from the economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. With a median student loan debt burden in New York of less than $20,000, the president’s debt-cancellation plan would eliminate at least half the outstanding debt for most of the state’s student borrowers. In conjunction with the unveiling of his debt-cancellation plan, the president also announced that regular monthly repayments of all other outstanding student loan debt would—after a nearly three-year pause—once again be required, but not until January 2023.

With a median student loan debt burden in New York of less than $20,000, the President’s debt-cancellation plan would eliminate at least half the outstanding debt for most of the state’s student borrowers.

At least six lawsuits by opponents of the president’s debt-cancelation plan were filed, with some advancing through the courts. In November 2022, a ruling by the Eighth Circuit of the US Court of Appeals overturned a lower court’s judgement and put the entire program on hold. Similarly, a ruling by the Fifth Circuit left in place a Texas court’s ruling that the plan was unconstitutional. In response, the administration offered yet another pause on student loan repayment requirements to allow time for the legal questions to be resolved: currently, repayment requirements are suspended until 60 days after litigation over the plan is settled or 60 days after June 30, 2023, whichever occurs first.

The Biden administration appealed to the US Supreme Court to reinstate its loan-cancellation program, and by mid-December, the Court agreed to combine and hear arguments on the two cases.

Opposition Makes it to SCOTUS

On December 1, 2022, the US Supreme Court (SCOTUS) agreed to hear Biden v. Nebraska, a case filed by six states—Nebraska, Missouri, Arkansas, Iowa, Kansas, and South Carolina—claiming that the Secretary of the US Department of Education does not have the legal authority to implement the proposed debt-relief program without the authorization of Congress, and that the plan violates the laws governing federal agencies. Less than two weeks later, SCOTUS agreed to grant a combined audience to arguments on Department of Education v. Brown, a Texas case, in which two student borrowers, Myra Brown and Alexander Taylor, claimed injury because their student loans are not covered in the proposed relief program, and had the US Department of Education followed proper administrative procedures and given them a chance for comment, they would have argued for a broader program of relief that included them.

Observers of the high court see SCOTUS as having two primary issues to resolve: first, do the litigants have proper standing to sue; and if so, then second, does the president and the Department of Education have the authority to cancel the loan debt as proposed? The fate of the Biden administration’s student loan debt cancellation program hangs on the decision of these two key questions.

The Arguments

The Plaintiffs

In Biden v. Nebraska, the joint petitioners assert that the state of Missouri operates the Missouri Higher Education Loan Authority (MOHELA), “one of the largest holders and servicers of student loans in the United States,” and that wiping out existing loan debt would could cost MOHELA as much as $44 million annually, drastically reducing its ability to contribute to the state’s funding of higher education institutions and programs. It is on this basis that the petitioners assert that Missouri has standing to sue as an injured party.

Other petitioner states note, with respect to establishing standing, that they calculate state taxable income based on taxpayers’ federal adjusted gross income (AGI), and because existing federal law excludes the value of discharged loans from counting as part of AGI until the year 2026, they will experience reduced revenue under the administration’s debt-cancellation plan.

In Department of Education v. Brown, the plaintiffs argue that to prove standing they don’t have to demonstrate that they would be successful at influencing a change in policy that broadens the program so their debt would be relieved; rather, they claim the department erred by simply not giving them the procedural chance to do so.

After deciding whether the plaintiffs have proper standing to sue, SCOTUS will turn to the legal substance of the case. Here, the plaintiffs’ arguments are predicated on the administration’s reliance on the HEROES Act of 2003. That law was enacted as a policy response to the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, and, in part, gives the secretary of education the authority to suspend regulatory provisions of federal student loans so that “recipients of student financial assistance… are not placed in a worse position financially in relation to that financial assistance” because of a national emergency. While the states’ lawsuit concedes that the declaration of a national emergency for the COVID-19 pandemic meant that the HEROES Act would allow the Department of Education to protect student loan borrowers from becoming worse off financially, they hold that “the Biden administration’s program actually places over 40 million borrowers in a better position by cancelling some or all of their debt.” The lawsuit continues: “…the Secretary uses it here to place tens of millions of borrowers in a better position by cancelling their loans en masse… The Act does not allow the Secretary to effectively transform federal student loans into grants.” Adding support to this reading of the law, the plaintiffs note that in 2020, Congress rejected specific legislation that would have discharged up to $10,000 in student-loan debt per borrower.

Finally, the plaintiffs make a handful of other arguments, including that the administration’s plan is “arbitrary and capricious.” And, that such drastic action as cancelling a massive amount of outstanding student debt—a typical estimate puts the total at around $430 million—improperly ignored what they contend are more reasonable options, such as extending borrower’s repayment periods.

The Defendants

On January 4, 2023, the US Department of Justice formally filed its brief in defense of the Biden administration’s plan.

The administration argues that first, the plaintiffs in the states’ case have no standing to sue on the basis that Missouri’s student loan servicer, MOHELA, is a separate corporation and thus the state of Missouri is not the proper entity to sue. Even so, the defense brief notes, the projected revenue loss is “pure speculation” that may in fact never materialize, and so the presumed future financial impact is not—at least now—financial injury. They further argue that the other states’ claim of injury relies on their own policies that use federal AGI as a driver of their state income tax collection. Thus, any damage from excluding the value of discharged loans from AGI, is a “self-inflicted” the administration claims, and not a result of the president’s student loan cancellation plan.

Regarding the individual borrowers from Texas, the administration’s brief points out that resolving their argument will not mean any benefit to them, but simply that “nobody gets any debt relief at all.” Essentially, there is no direct injury, and the fix would result in no benefit.

Looking past the questions around sufficient legal standing to sue, the brief argues that the debt-cancellation plan is legal nonetheless, that its provisions “fall comfortably” within the law, that they enjoy “clear authorization” from Congress.

As noted above, the administration’s debt cancellation plan relies on the clear authority provided by the HEROES Act for the Secretary of Education to modify the student loan provisions to provide relief during a national emergency. This is the same policy cited by President Donald Trump’s Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos as justification for the very first pandemic-related pause of student loan repayment requirements, and this authority was cited time and again as the repayment pause was extended multiple times throughout the Trump and Biden administrations.

In its defense brief, the Justice Department ties the debt-cancellation plan to the restart of student loan repayments, stating that “ending that pause without providing some additional relief for lower-income borrowers would cause delinquency and default rates to spike above pre-pandemic levels.” That is, the administration is well within its authority under the HEROES Act to enact the proposed debt relief plan because it protects student borrowers from becoming worse off financially.

Supporting Briefs

Dozens of amicus curiae briefs have been filed in the case supporting one side or the other, adding a variety of thoughtful perspectives, legal support, and strongly advocated positions on the issues at hand. Not all offer complete clarity: in one brief, in fact, two law professors state their view that the proposed program is “unlawful,” but yet still urge the court to rule against the plaintiffs because the legal theories offered on their behalf are “wrong.”

Other Considerations

Complicating things for the Biden administration’s case is the president’s decision to call an official end to the national emergency posed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Since impact of the pandemic on the nation’s social and economic condition was used as the foundation for the justification for debt relief, as one SCOTUS reporter posited, “if COVID-19 is no longer a national emergency, does the executive branch still have the authority to waive student debt?”

Interestingly, however, there may be an option on which to predicate the debt cancellation plan other than reliance on the HEROES Act and its basis of a state of national emergency. In September 2020, the Legal Services Center of Harvard University wrote a memo for then presidential candidate Senator Elizabeth Warren offering the position that the authority to cancel student loan debt has always existed under the broad-reaching federal Higher Education Act. And in February 2021, Senator Warren joined Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer and others introducing a resolution that outlined a plan for the Biden administration to cancel student debt using the “compromise-and-settlement” authority allowed under the Act, authority that has already been cited to offer relief in other instances, such as when a school closed or when the borrower became permanently disabled.

Regardless of how the case is eventually settled, it is worth policymakers keeping in mind that the elimination of any amount of existing student debt does nothing to stem the underlying increased cost of higher education or to ease the financial burden of tomorrow’s student borrowers. President Biden has acknowledged this critical perspective, bundling with his proposed debt-relief initiative a streamlining of available income-based repayment plans that could cut borrowers’ costs in half, initiating corrective policies to the burdensome Public Service Loan Forgiveness program, and enacting with Congress a record amount of need-based federal education aid through expansion of the Pell Grant program.

Conclusion

Does President Biden’s administration have the authority to grant broad-scale student loan debt cancellation, or is that a job only Congress can do? For the administration’s part, US Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona has stated that, “We remain confident in our legal authority to adopt this program that will ensure the financial harms caused by the pandemic don’t drive borrowers into delinquency and default. We are unapologetically committed to helping borrowers recover from the pandemic and providing working families with the breathing room they need to prepare for student loan payments to resume.”

The February 28 proceedings before SCOTUS may offer a glimpse of how the nation’s highest court will decide the issue.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Brian Backstrom is director of education policy studies