By Althea Brennan

Gender inequality remains a persistent problem in our society. While we now have more women than ever working, going to college, and acting as the primary breadwinner for families across the nation, research shows that there is a continued wage gap between women and men. Overall, the wage gap is 15 percent. However, data from the Institute for Women’s Policy Research show the gap is even wider for women of color: whereas white women make 82 percent of what white men make, black women make only 68 percent, and Hispanic women make only 62 percent.

Why is it that in a post-Title IX era, where more women than ever are attending law and graduate schools and entering the workforce in competitive, high-paying positions that the wage gap persists? The answer lies in our culture and the way we view, treat, and employ women.

Culture in the workplace and beyond has changed, however, and public policy is reflecting those changes. Progressive policies, like pay equity, childcare, and paid family leave are becoming increasingly prevalent, thanks in large part to the record number of women serving in legislative statehouses across the nation, in Congress, and running for the presidential nomination.

There are many common misconceptions surrounding the existence of the wage gap. It is not necessarily that women look to take lower-paying jobs, or are attracted to “softer” careers such as teaching, nursing, and administrative assistants. Instead, it is that women are responsible for a disproportionate share of childcare. Despite fast-paced social change, nearly 60 percent of women are the primary caretaker in American households. Moreover, women are far more likely than men to pick up the “second shift,” a term coined by sociologist Arlie Hochschild to describe the role women play in the traditional family. Finally, women are also more likely to be employed in lower-paying professions that have more of the flexibility needed when the employed also takes the role of primary caregiver. It is precisely because men, in most cases, do not take an equal role in child-rearing that many women must take jobs that are more accommodating and flexible. And those jobs almost always have less room for promotions and pay substantially less, resulting in lower lifetime pay and less viable upward mobility.

Because of the second shift, fewer women are able to pursue promotional tracks. For example, New York State Labor Commissioner Roberta Reardon raises the example of women in the medical field [1]. While an equal number of men and women attend medical school, a disproportionately large number of surgeons are men. The age that a woman traditionally is leaving medical school and entering into her residency coincides with peak childbearing years. Those women may, and often do, choose to enter fields that are more accommodating to childcare, like pediatrics. Outside the medical field, many middle-income women must decide whether to spend more than half their income on childcare; leave the workforce entirely; or take alternative, more accommodating employment. Lower-income women may not have a choice either way, and are forced to work without the ability to afford quality childcare.

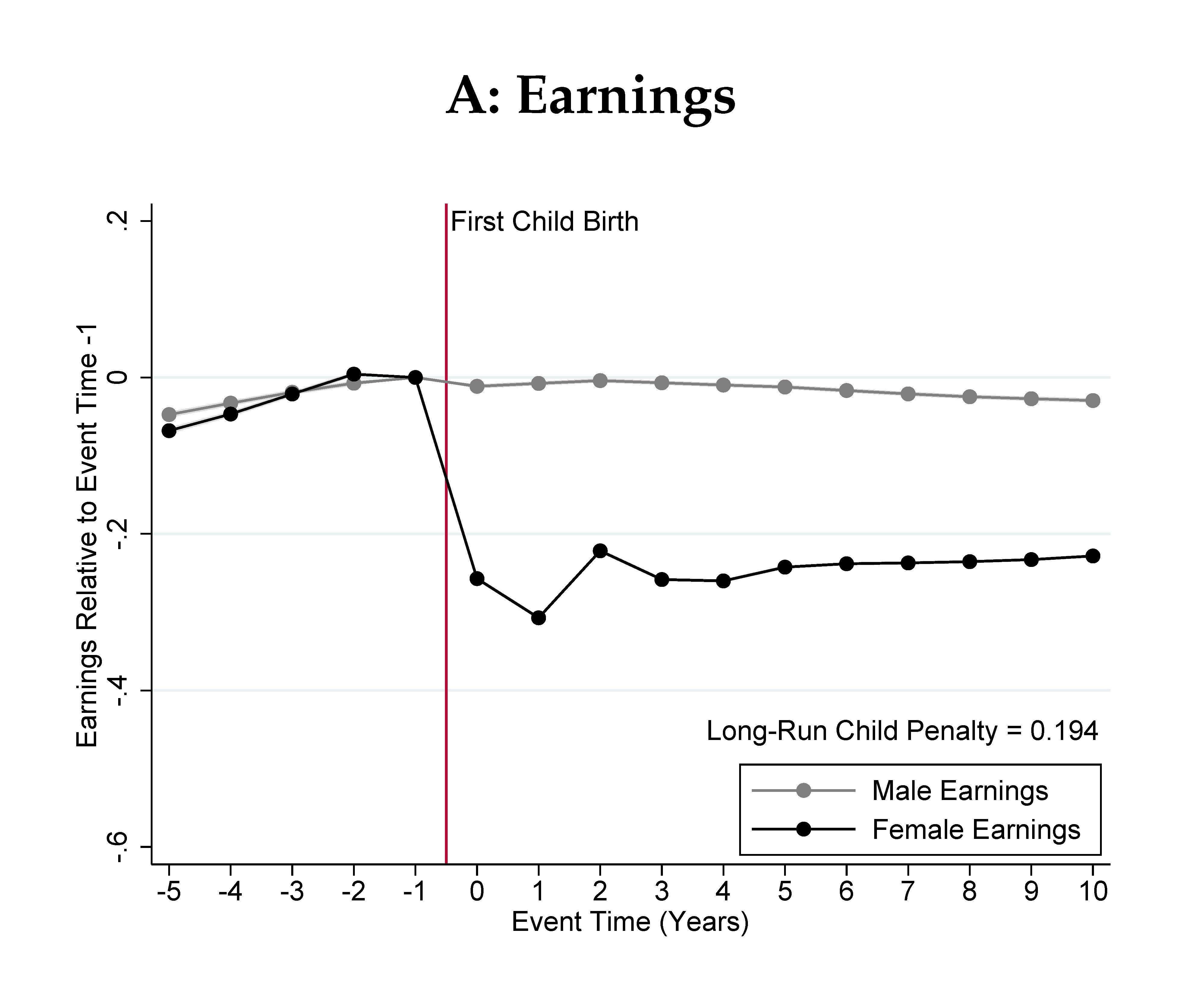

The burden of domestic labor results in lower lifetime pay for women. For example, Henrik Kleven, a Danish economist at Princeton University, found in the Danish workforce that women receive a “child penalty” — the phenomenon of women’s earnings falling sharply when they have children. More specifically, Kleven’s data show that, while women make less than men across the board, women who do not have children do not experience the same drop in income that women who have children experience. Kleven found that after having children many women adjust their employment while men do not, resulting in a 20 percent wage disparity between Danish men and women (see Figure 1). Unequal family and household burdens may explain why women enter into law school and receive MBAs in equal proportion, yet only a small portion of CEOs and partners are women. A reduction in wages, career esteem, and employment probability then ensues.

Source: Kleven et. al., “Children and Gender Inequality: Evidence from Denmark.”

The culture around child-rearing affects the economics of the wage gap. In recent years, wealthier women have coined the term “the opt-out revolution,” in which women leave the workforce to raise their children, often leaving behind career paths that would have led directly into boardrooms at Fortune 500 companies, operating rooms, and partnerships at prestigious law firms. This revolution, while undoubtedly contributing to the wage gap, does not accurately encompass the problem most American women face. Women are far more likely to work low-paying jobs with schedules that are subject to change and be unable to afford the exorbitant price of childcare. When low-income women have children without access to paid leave, job protection, or quality, affordable childcare, they are more likely to leave their jobs or be forced to take other jobs in fields that are better equipped for child-rearing. Over time, this choice compounds, resulting in the wage gap.

There is no silver bullet to address all of the problems discussed; however, the veritable cocktail of solutions available to us is extensive and growing. The Closing the Gender Wage Gap in New York State study, published in April 2018, identified 40 actions that can be taken to address gender pay disparity, not all of them traditional. Solutions include instituting a salary history ban, expanding the New York State mentoring program, increasing salary negotiation training, and incentivizing employers that provide funding for childcare, amongst a host of others. Through a combination of incremental changes, big picture ideas, and sweeping reforms, we can begin to chip away at this centuries-old problem.

One viable option to address the labor market effects of childbirth is paid family leave. Paid family leave requires employers to provide job-protected time off, generally between eight and 12 weeks, with some portion of pay. Currently, the federal Family and Medical Leave Act provides protected unpaid time off, but poor and middle-class women cannot take advantage of it.

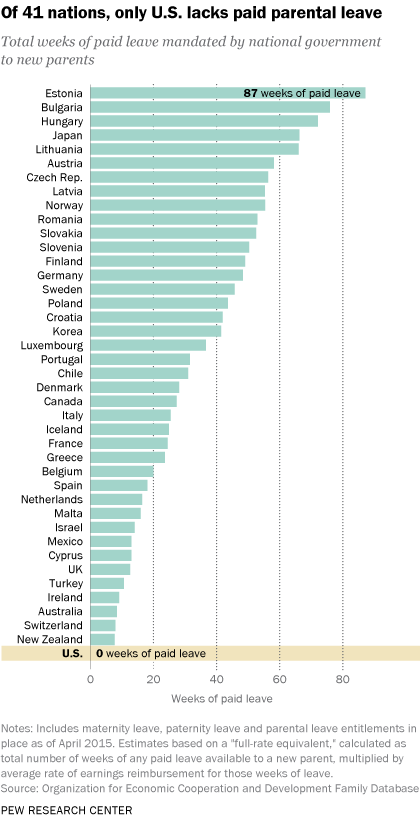

At the state level, New York is ahead of the curve. In 2016, Governor Cuomo signed the New York State Paid Family Leave Act, the most progressive paid family leave law in the country. When the 2016 law takes full effect, mothers, fathers, grandparents, and other primary caregivers — including foster and adoptive parents — will be eligible for 12 weeks of leave at 67 percent of their salary. Paid-leave laws, like New York’s, which are now present in five states and the District of Columbia, and virtually every other country around the world (see Figure 2), alleviate much of the stress after birth for parents. These laws allow and encourage women to reenter the workforce after giving birth, and encourage men to take time off as well to aid in some of the early child rearing.

Source: Livingston, “Among 41 nations, U.S. is the outlier when it comes to paid parental leave”, Pew Research Center, September 26, 2016, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/09/26/u-s-lacks-mandated-paid-parental-leave/.

The results of paid leave in other states are auspicious. California, the first state to enact a paid leave law, saw a 6 to 9 percent increase in hours worked and wages earned for new mothers in short-term labor market outcome, higher work and employment probabilities for mothers nine to 12 months after leave, and increasing job continuity and labor force attachment. There are also potential long-term benefits to paid leave, including increasing lifetime earnings and retirement security because the law allows and encourages women to stay at the same job after having a child, thereby minimizing the wage gap. In California, paid leave led to a 6 to 9 percent increase in wages in the medium and long term. Additionally, families who had access to paid leave were 39 percent less likely to receive public assistance the following year compared to mothers who did not take leave.

Most importantly, paid family leave laws have the potential to transform the workplace and social culture. Every paid leave law includes provisions for both men and women to take leave. Indeed, the number of men taking at least a week has increased since California enacted their paid leave law in 2004. However, women are still much more likely to take leave than men.

According to Commissioner Reardon, the single best thing employers can do for women is to encourage male employees to take paternity leave. When both men and women take leave, the workplace is forced to address the stigma around employing women of childbearing age because of potential absence due to childbearing, as men would be encouraged to take that time off as well. When the workplace begins to shed light on the taboo of child-rearing as a professional, early steps towards change are made. Moreover, there is no financial burden to hire women or encourage employees to take leave. Thus, the barriers that women face in hiring practices, as well as the social stigma around childbearing that affect them in the workforce, may begin to crumble.

However, paid family leave laws are not universally supported, particularly not by the business community because of the cost to employers. However, a 2013 survey done in California found that businesses, which typically spend 21 percent of an employee’s annual salary when turnover occurs, enjoyed “a positive effect” or “no noticeable effect” on turnover post-paid family leave, saving an estimated $89 million annually in turnover reduction. The New York State Paid Family Leave law is funded by payroll deductions from all employees, and while it is a cost, it is relatively small. California, with a population of nearly 40 million, acts as an indicator of the success paid leave programs can have on large, diverse populations. This success extends beyond the employee, and ends up benefitting businesses in the long term by reducing turnover costs.

Paid family leave laws have the potential to change the workplace culture by not only opening up the possibility of taking leave to mothers and fathers of all socioeconomic classes and professions, but also breaking down the stereotypes women in the workplace face when they become mothers. While paid leave can open up career opportunities and strengthen family structure and economic stability, more can be done. A variety of workplace policies can be implemented in both the public and private sectors to help address the unequal burden of domestic labor by women. Many of these policies do not require a legal mandate, and some are incredibly easy for employers to institute. For example, some of the proposals in the Closing the Gender Wage Gap report, and referenced by Commissioner Reardon, include ways the government can encourage social change and open the eyes of employers and the public to the gender pay disparity, such as an educational campaign to get more men to take paid leave. Other proposed changes are statutory, such as establishing protections for workers with unpredictable schedules or eliminating the subminimum wage for tipped workers.

Other states have also begun to institute policies aimed at addressing the burden of domestic labor, such as the six states that have “bring your baby to work” programs, where new parents may take their newborns into the office so they are able to continue work. In New York, the Department of Labor has spoken of telecommuting as a way to keep women in their jobs and engaged in the workplace when trying to manage the work-life balance that is brought when rearing children. Many of these proposals aim to create small, incremental changes that would reduce much of the stress of trying to balance both domestic and professional labor.

The aim of these programs is not only to alleviate some of the obstacles that working mothers face, but also to address an overall lack of awareness. People may not realize an unfair division exists between men and women, or have little idea how to address it. By promoting paternity leave, one encourages parents to share child-rearing at the beginning of life, when parenting is still new. At the same time, if both parents take leave, the perceived disadvantage of hiring a woman who is a mother, or may become a mother, may also go down. The logic is simple: if men are more involved in child-rearing and take more child-related absences from work (such as leaving to care for a sick child), employers will come to expect these absences and will establish a degree of flexibility for all employees, regardless of gender.

Obviously, these outcomes are best-case scenario, and that is okay. If we can make small changes that have the potential to adjust the social issues and labor disparities between men and women, we could begin to narrow the wage gap. In a workplace where parents can more effectively manage child-rearing, where more women are present and earning, and where the wage gap has narrowed there are no losers.

By requiring paid family leave, government can help change the workplace culture. More than that, it can have a ripple effect beyond that office and into society at large. It becomes a task on all of us — employers, employees, and policymakers — to shift the way we view modern employment. If the burden of domestic labor were more equal, and access to childcare was universal, the defining question of the wage gap issue becomes how do we, in the workforce, ask men to act more like women, as opposed to asking women to act more like men.

[1] Interview with New York State Labor Commissioner Roberta Reardon on March 26, 2019.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Althea Brennan is a former New Visions: Law & Government student who interned at the Rockefeller Institute of Government