June 2014

Internationalization of colleges and universities historically has been fostered—and continues to be fostered—mostly by grassroots efforts by faculty and staff members, driven by bottom-up rather than top-down approaches. More recently, though, national governments have become drivers of the internationalization of higher education, particularly because it relates to public diplomacy, national security, and economic development. But how do sub-national entities, such as state governments and their agents, influence the internationalization of higher education? This question is critical to U.S. colleges and universities, for while the federal government has played a supportive role in this agenda, higher education is primarily the responsibility of state and local governments. Our research has found that a growing number of states are emerging as influential actors in international education efforts. This report provides an initial analysis of these previously unreported state-level trends, investigating the drivers and tools of state-level involvement in international education.

Historically, most of the internationalization of higher education has been driven by grassroots efforts at colleges and universities such as collaborative research projects, student exchanges, and faculty adaptation of curriculum.

More recently, because of its connection to national security, economic development, and public diplomacy, international education has begun to attract more significant interest from national governments around the globe. In most countries, primary responsibility for higher education falls on the national government. In the United States, however, state governments retain primary authority over public higher education, and almost no attention has been given to state-level involvement in the internationalization of higher education. This report provides an initial analysis and description of what motivates state governments and their agents (e.g., system offices and coordinating boards) to engage in the internationalization of their colleges and universities.

While there has been much effort by institutions to internationalize at home through curricular offerings and internationally oriented student activities, most governments, state and national, are interested in promoting mobility. International academic mobility generally consists of the movement of students, faculty members, programs, or institutions across borders, the most prevalent of which is the movement of students. Exchanges include both U.S. students’ study in foreign countries and foreign students’ enrollment in U.S. colleges and universities. The United States has been the most popular destination for studying abroad. The Institute of International Education (IIE) reports that about 820,000 international students enrolled in the United States in 2013, a 40 percent increase since 2001.

However, the U.S. market share is declining. In 2000, the United States educated 23 percent of all students who were studying abroad. By 2011, its share fell to 16 percent.

The drop in enrollment share reflects several global trends. First, other English-speaking countries, such as Canada, Australia, and the United Kingdom, aggressively recruit students from other nations.

In many other countries, national governments have promoted and expanded educational opportunities for foreign students. In addition to other popular English language countries, graduate programs in non-native English nations have also begun to

offer coursework in English.

Second, certain countries or regions have been able to leverage system-level approaches to internationalization, including strong marketing campaigns in Asian-Pacific countries and regional mobility policies in the European higher education area. It is also important to note that U.S. students study abroad at a much lower rate than do their peers in many other mature economies. In 2013, approximately 283,000 American students studied abroad for academic credit. That represents a 300 percent increase over the course of only two decades.

Yet the total represents only 1.4 percent of all postsecondary students enrolled in U.S. colleges and universities. The small fraction does not represent a lack of interest. A report published in 2008 by the American Council on Education; Art & Science Group, LLC; and the College Board indicated that only 5 percent of students who want an international experience during their college career actually participate in one, suggesting that there is interest in study abroad even if students are not engaging in existing programs.

The involvement of so few students in study abroad can put a nation’s long-term global competitiveness at risk. A recent report about the importance of study abroad framed the issue in this way:

On the international stage, what nations don’t know can hurt them. Whether the region is Europe, Asia, Africa, Latin America, Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union, or the Middle East, whether the issue involves diplomacy, foreign affairs, national security, or commerce and finance—what nations do not know exacts a heavy toll. The stakes involved in study abroad are that simple, that straightforward, and that important. Promoting and democratizing undergraduate study abroad is the next step in the evolution of American higher education. Making study abroad the norm and not the exception can position this and future generations of Americans for success in the world in much the same way that establishment of the land-grant university system and enactment of the GI Bill helped create the American century.

However, while research and policy documents have begun to frame international education as a national issue, there has been almost no effort to understand what interest and role there might be for state governments. We take on this issue in this report.

An important caveat is that the structure of each state’s higher education sector differs; how, and to what extent, each state engages with its higher education sector will vary. Almost all states have created coordinating agencies or multi-campus systems as a means to oversee some or all the public institutions in the state. We include the activities of these entities that act on behalf of the state but are distinct from individual institutions. While the focus of this report is on the state level, it is important to understand how state-level engagements fit within the context of what individual institutions and the national government are doing. We explore these differing motivations in the following sections.

With regard to engagement in international education, campus motivations primarily tendto be oriented toward academics, economics, and prestige. Academic programs are often the core motivation for faculty members to develop a study abroad program, invite visiting scholars to teach a specialized course, or collaborate across institutions to advance research and learning. The OECD calls this the mutual understanding approach, where building cultural and academic networks are at the forefront of international exchange.

A second prominent driver of campus efforts is economic in nature, often regarded as a revenue-generating mechanism to supplement other revenue sources, sometimes offsetting declines in state support. Some public campuses levy much higher fees on international students than on domestic students—usually two to three times the in-state tuition rate—in an effort to close budget gaps and cover the costs of campus programs.10 The World Bank estimates that $300 billion is spent each year on global higher education, study abroad, and other international programs, and there is no sign that this spending will slow down.

Finally, coupled with academic and economic motivations are prestige and status building. As with most sectors, an industry has emerged around higher education to help students, families, businesses, and governments figure out exactly what is going on inside the ivory tower. Campuses are matched against each other in ranked lists of best to worst, most famously in U.S. News & World Report, but these rankings are increasingly global in scope, such as the Times Higher Education World Reputation Rankings and Shanghai Jiao Tong University’s Academic Ranking of World Universities. Internationalization efforts help campuses boost their reputation and perceived prestige, especially by enhancing research capacity.

While campuses are concerned with academics, economics, and prestige, the federal government has been motivated by economics, public diplomacy, and national security. Internationalization’s broad economic benefits to national economies are well documented. A study released in 2007 by the U.S. Government Accountability Office reported that international students have been “important sources of innovation and productivity in our increasingly knowledge-based economy, brought needed research and workforce skills, and strengthened our labor force.”

For example, in 2011, international students, post-docs, and other non-faculty researchers contributed to 54 percent of patents issued to universities.

In fact, some nations have begun to use cross-border education, such as international branch campuses and academic partnerships, as tools for economic and capacity development.

With regard to public diplomacy, many countries continue to invest in and see the important role of higher education in the cultural, economic, and political relationships between nations. For example, the United States government invests about $230 million every year in the Fulbright program, perhaps its most popular international program.

The Department of State hosts a variety of other programs through the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs, while USAID has historically sponsored educational projects to advance the federal foreign policy agenda, both formally and as soft power.

National security interests emerge in various ways with regard to the federal government’s role in international education: Security was a major theme in the National Defense Education act of 1958, the creation of the Student and Exchange Visitor Information System (SEVIS) following the attacks on September 11, 2001, and continues to influence federal perspectives on immigration and information safety.18 More recently, the federal government formed an advisory board to help protect intellectual property that is created and disseminated on U.S. campuses, specifically citing the increase in global cross-border education activities.19 Finally, immigration debates are central to internationalization efforts as the country’s immigration policies dictate who can enter and stay in the United States and what they may do while they are here.

So where do the states fit in the agenda for internationalization of higher education? Do they choose to engage in international education? If so, why? There is growing rhetoric among state leaders and policymakers that the primary role of the state in higher education is to

ensure that the collective system is able to fulfill the public agenda—that is, the well-being of the state, generally speaking.20 Historically, the well-being of a state has been understood domestically; states’ stances have ranged from ambivalent to hostile on higher education’s international efforts. As a result, states have engaged in very little oversight of the international activities of their public colleges and universities, usually only restricting the use of state dollars in out-of-state activities.21 Moreover, many institutions have downplayed their international engagements for fear that state-level elected officials may raise concerns about their out-of-state focus.

More recently, though, state governments and their higher education coordinating entities have shown new interest in international engagements, largely driven by the need to make their economies globally competitive. In the case of international higher education,

our research has found that state governments and their higher education coordinating entities serve the public interest through

(1) economic development,

(2) enhanced efficiencies, and

(3) quality assurance.22 We should note that the motivations have different impetuses.

The economic development perspective comes from a recognition that higher education can help advance the state’s economy, while the enhanced efficiencies and quality assurance are driven by interests in how colleges and universities engage in internationalization activities.

Similar to campuses and the federal government, states are cognizant of the implications to economic development that global initiatives bring. As recent research indicates, “many rust belt states are looking to transform themselves from a state dependent on manufacturing and agriculture to a more diverse knowledge-based economy.”23 An important means for transforming an economy is through the mobility of students and scholars. States recognize that international students contribute to regional economies not only during their studies, but also often after they graduate by remaining in the area and adding new global dimensions to local industry. In fact, international students account for about 15 percent of graduate enrollments nationally (compared with about 4 percent at the undergraduate level).

Those proportions are far higher in STEM fields. In 2007, the percentage of science and engineering

doctorates awarded to international students exceeded 40 percent. Moreover, about 35 percent of post-docs are temporary visa holders. Internationalization is more than simply encouraging the movement of people. Colleges and universities have become important drivers of economic development in both the domestic and international arenas. They help raise the international awareness of their local region. The University at Buffalo (UB), a State University of New York campus, noted it this way in its economic development impact report.

With the heavy international presence at its campuses, UB plays an important role in expanding the global awareness of Buffalo Niagara. For many overseas, the first time they hear of Buffalo is when they hear about UB. This association helps to cultivate an international image of Buffalo Niagara as a region that is plugged into the knowledge-based economy. Closer to home, UB’s national profile assist efforts to rebrand the region from a snowy factory town to a center for innovation.28 This effect happens in communities across the United States. State government leaders are beginning to recognize that their colleges and universities not only help attract students and scholars. They can be critical for transforming the economic base of their communities and communicating that change to the outside world, helping to attract international trade and foreign direct investment for local companies.

The state also finds itself in the position to leverage efficiencies through economies of scale and value-added measures such as shared services.30 In the 1960s and 1970s, states developed coordinating agencies to help identify efficiencies across their public higher education systems. With a few exceptions, these system offices, agencies, and coordinating boards rarely dealt with international education issues. However, in the early part of the 21st century there is evidence of growing engagement by such entities in the development of a global presence for their state systems and the creation of efficiencies through shared programming in study abroad, foreign language offerings, and international student recruitment.

Finally, states have a historic role in managing quality assurance of the academic programs offered within them. This role includes the prevention of diploma mills, an issue that has

mostly been about shutting down non-accredited institutions. However, as international programs have proliferated, concerns over quality have grown with them. The states’ policy and regulatory authority endows them with the ability to reduce liabilities and mitigate risks, helping campuses and students participate in vetted programs. Currently, Minnesota and New York are considering legislation that would require colleges to make information about their study abroad programs publicly available. The Minnesota bill is oriented around student safety while the New York bill is geared toward financial transparency. While some members of the higher education community are uneasy about increased government regulation, both bills have some support from academe.

Recognizing the importance of a highly educated workforce in a knowledge-based and increasingly global economy, U.S. states and public higher education systems have begun to formalize internationalization efforts through gubernatorial proclamations, legislative resolutions, foreign student recruitment programs, inclusion of internationalization goals in master or strategic plans, and increased funding for study abroad and exchange programs. These initiatives have been designed not only to produce world-class graduates who will secure gainful employment in a global workforce, but also to contribute to the economic vitality of the community and state in which the institutions are located. In many instances, policymakers are careful to note the economic impact that foreign students have on public institutions and the larger community.

To investigate the extent to which these trends exist, the Rockefeller Institute of Government (RIG), in cooperation with the Department of Educational Administration and Policy Studies at the State University of New York at Albany, undertook a national study to identify state initiatives to support internationalization activities. To gather baseline data about the ways in which international education is promoted at the state and system levels, a brief (17-question) survey was sent to the state higher education executive officer (SHEEO) in all 50 states. Due to the well-documented differences in state higher education governance structures, some survey respondents represent state agencies, while others represent comprehensive public systems. Since all survey respondents are the state-designated SHEEO, this report treats state agencies and system higher education governance as similar state-level groups (see Figure 1).

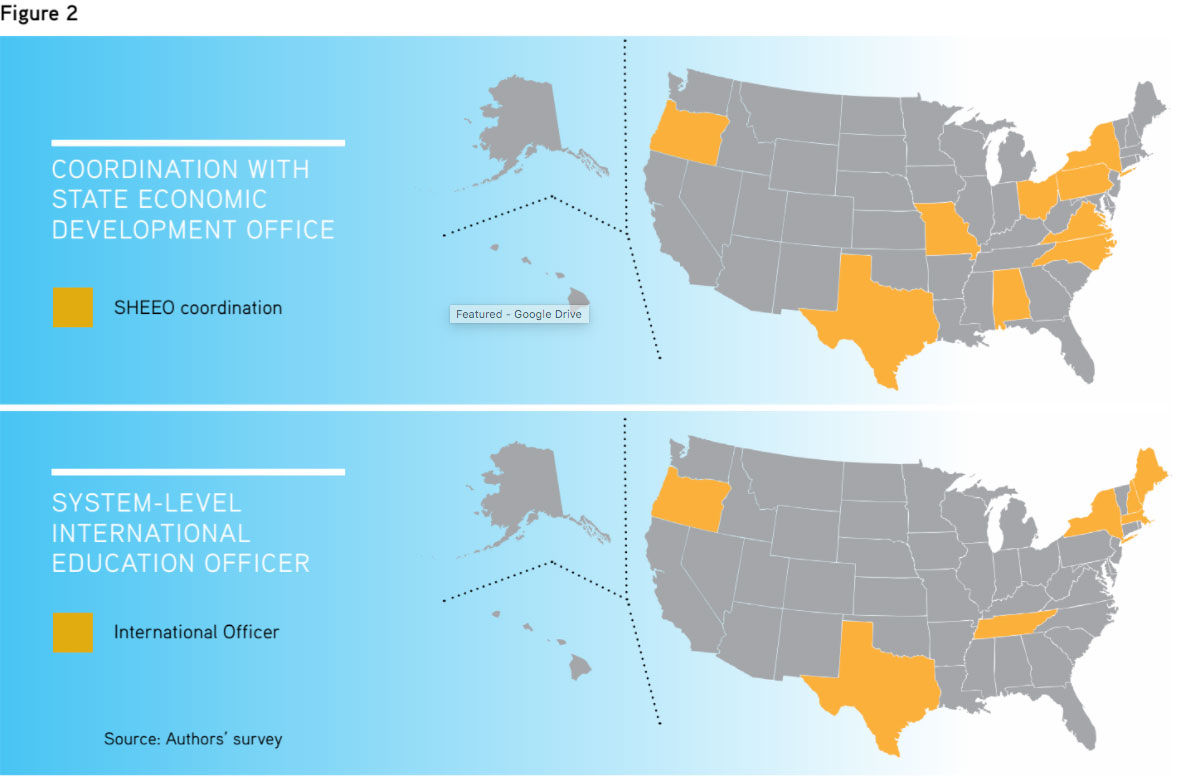

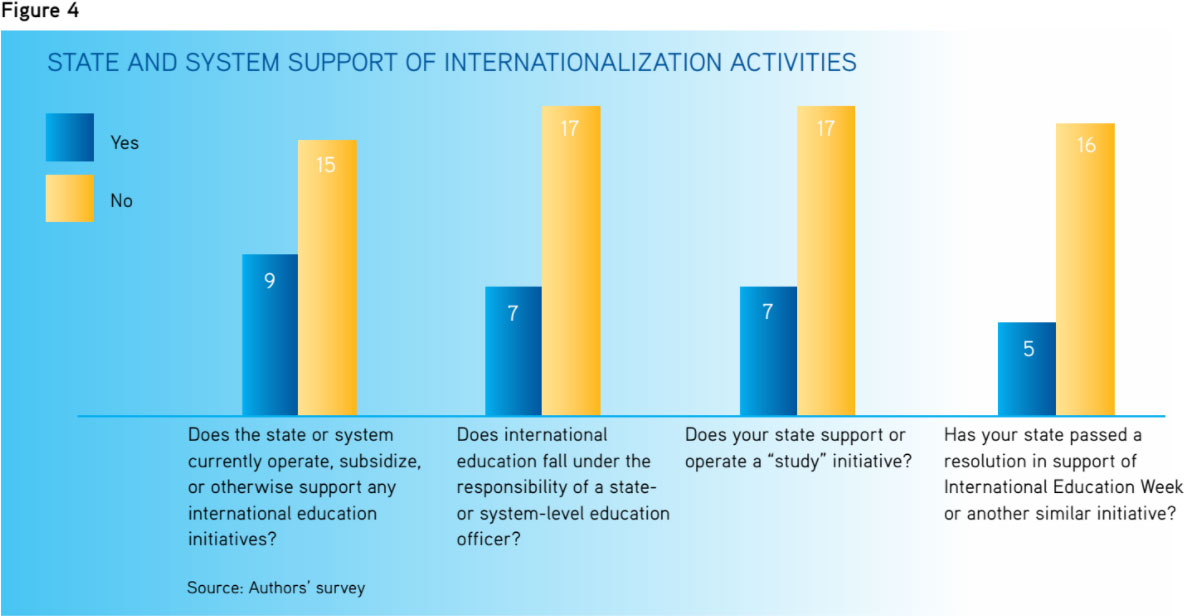

Researchers requested information about any statewide initiatives to foster international education, partnerships with other state offices with international interests (e.g., the state department of commerce), and areas of responsibility for those efforts. State master or strategic plans were reviewed to identify the initiatives and strategies (if applicable) that were being employed at the system level to promote internationalization. Finally, scholarly literature, relevant policy documents, and grey literature (e.g., websites, media reports) were analyzed to assess what other information has been published on the topic and related efforts. Of the 50 surveys sent, 26 states responded, with each region of the country represented. As Figure 2 illustrates, the majority of states and public systems in this sample have not, as yet, established formal administrative structures to guide and manage internationalization efforts.

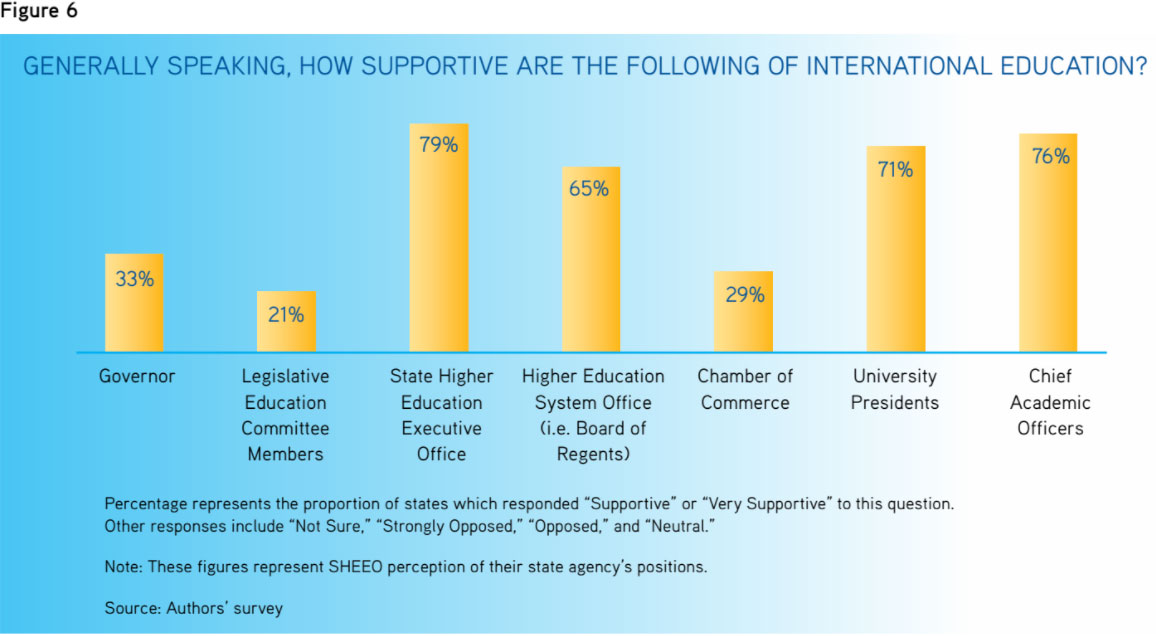

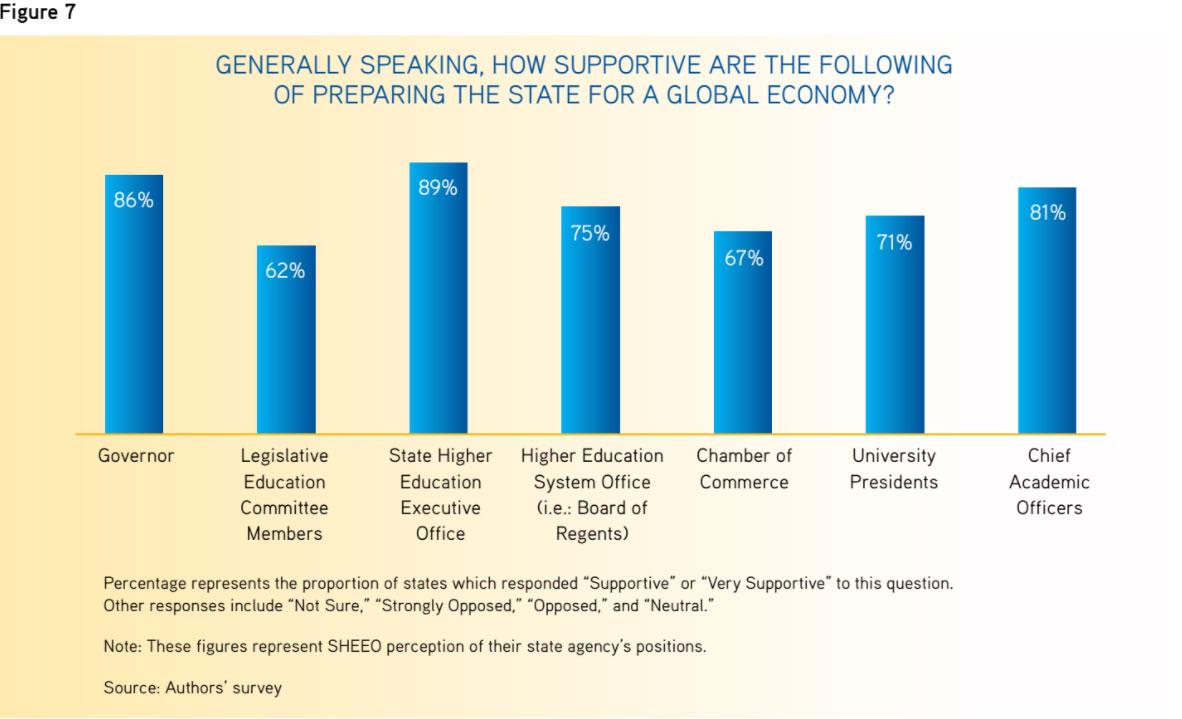

For example, we identified only seven states or systems that have a state- or system-level officer for international education. Although only a small number of survey respondents reported formal administrative coordination, our survey revealed that many state leaders are supportive of higher education internationalization efforts. For example, 79 percent of respondents agreed that their state’s higher education executive office is supportive of international education, and 65 percent believed that their state’s system office support these efforts.

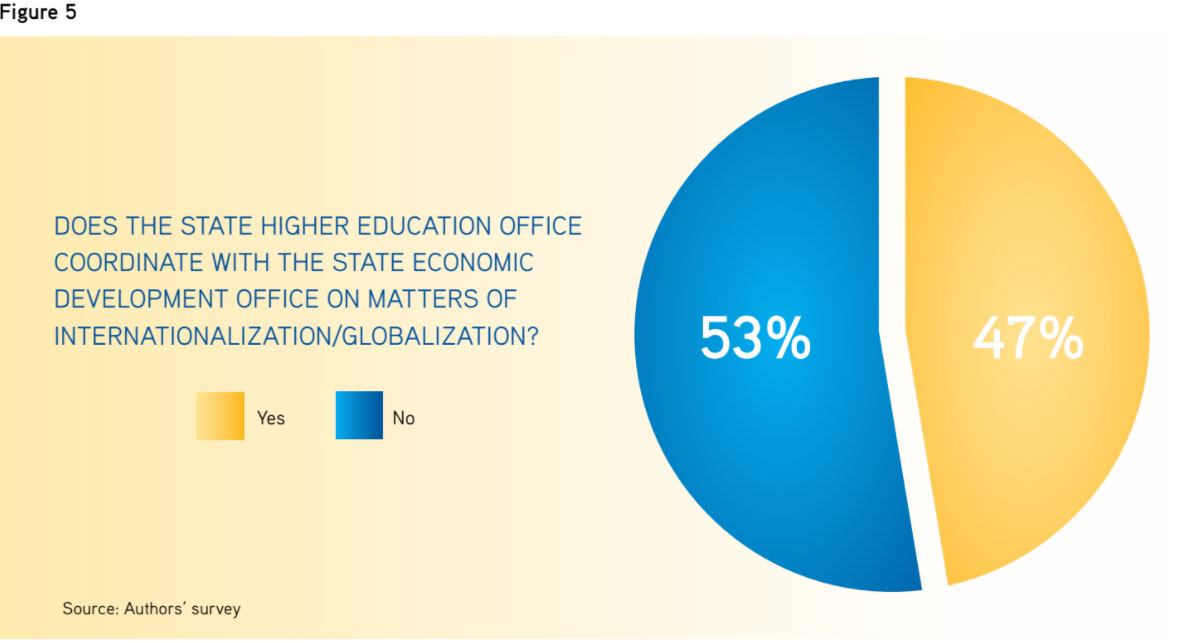

It is important to note that, regardless of having an international education officer, 40 percent of respondents (nine states) agreed that the state system higher education office coordinates with the state economic development office on global matters. In Missouri, for example, the higher education office works with the Department of Economic Development’s International Business Development Group, which has provided technical assistance to members of the Study Missouri Consortium. One respondent wrote that marketing materials for the state’s higher education sector are on display in international economic development offices in other countries. Further, in a number of states including Virginia, New York, and Tennessee, greater collaboration between higher education and economic development agencies is being explored and formalized.

As discussed previously, extant research has identified core state motivations for getting involved in internationalization, namely economic development, scaled efficiencies, and quality concerns. This baseline survey and analysis of the grey literature has allowed us to identify the extent to which states and public systems are intentionally incorporating international higher education in their public policy agenda. In other words, what are states actually doing? Observed efforts have been synthesized into four themes or pillars of action: (1) developing an international higher education policy agenda; (2) strategic planning and goal setting; (3) international exchanges and study abroad; and (4) collaborative and innovative research programs. While they might seem to progress in a certain order—i.e., first create an agenda, then create an initiative—states develop their internationalization efforts through many pathways. These pillars of action sometimes occur simultaneously and differently within each state.

State governments typically begin to support internationalization efforts by formally recognizing the importance of global higher education to the public mission. This first pillar of action takes advantage of a fundamental characteristic of state-level governance: the ability to shape and advance important current issues, bringing them to the foreground of public discussion. States use policy tools that flow through either their legislative bodies or their governor’s office, via an executive agency. Our research found that legislatures typically use tools that allow them to encourage rather than mandate, particularly non-binding resolutions, which generally have no force of law. Governor’s offices have often chosen to link global higher education to consortia in executive agencies or nonprofit organizations designed to emphasize targeted themes, such as economic development or global citizenship.

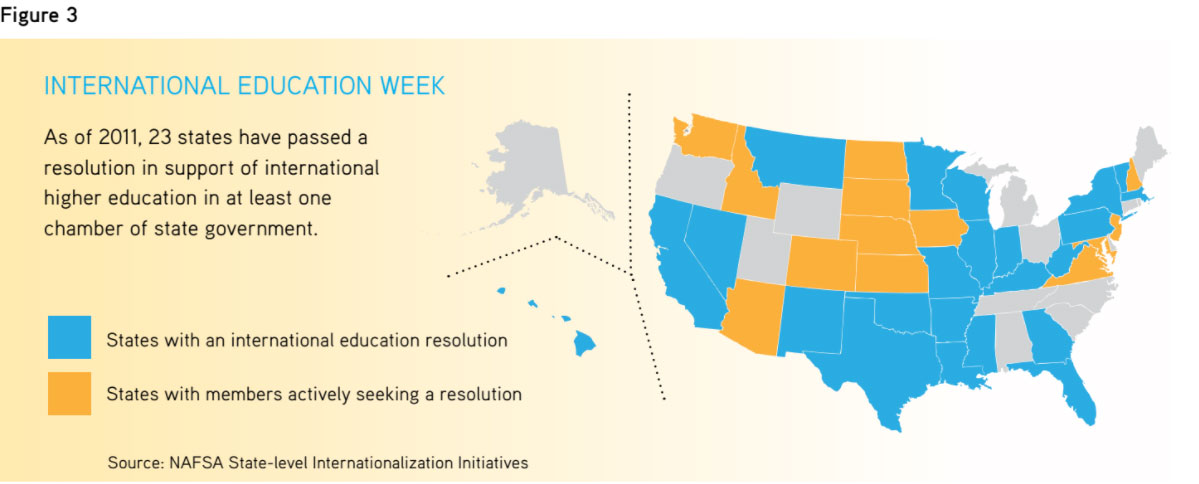

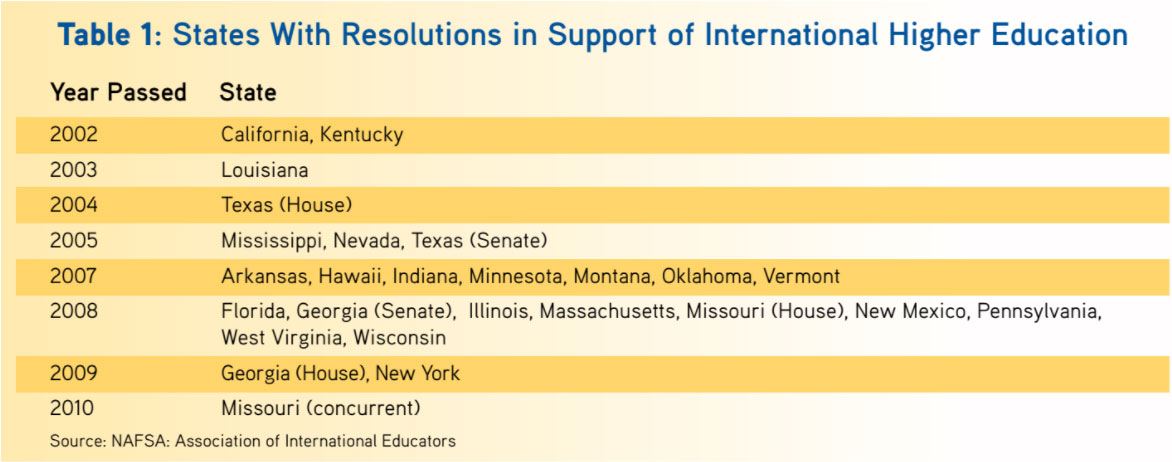

As of 2010, there had been at least 29 gubernatorial proclamations related to international education; since 2002, 23 state legislatures have passed house, senate, or concurrent resolutions to encourage public and private colleges and universities to place a high priority on international education (see Table 1). These proclamations and resolutions generally share a number of common rationales: the importance of educating globally conscious students, the skills required for a global workforce, the scientific gains from collaborative international research, the economic contributions of global students to local and state markets, and the importance of tourism and foreign trade to state economies. As expressed in New York State’s 2009 resolution, “Providing the future leaders … with the broadest possible education will significantly impact our national security, foreign policy, economic competitiveness, economic revenue and capacity for tolerance.”33

The actions called for by the resolutions and proclamations vary, with most calling for recognition of the importance of international education and encouraging students and faculty members to participate in and promote curricular and extracurricular educational activities.

A few legislatures have pushed a bit further, encouraging higher education institutions to develop more academic programs with international foci, foreign language components, study abroad initiatives, and collaborative scholarly exchanges. Louisiana and West Virginia commended the efforts of established respective advisory committees or consortia. New Mexico went beyond higher education to include the importance of developing global skills in primary and secondary education as well.

Several resolutions mentioned how these declarations align the state public policy agenda with federal initiatives or the efforts of professional associations. The U.S. Departments of Education and State sponsor International Education Week, celebrated every November since 2000, to increase national awareness of the importance of international education.

New York and Pennsylvania used their resolutions to recognize the efforts of NAFSA: Association of International Educators (formerly known as the National Association of Foreign Study Advisors), a professional group of college and university officials developed to enhance opportunities for study abroad, participation in scholarly exchange programs, and the study of foreign areas and languages. NAFSA includes advocacy as a key component of its strategic plan, organizing its efforts around influencing public policy and disseminating information about the benefits of international education and exchange.

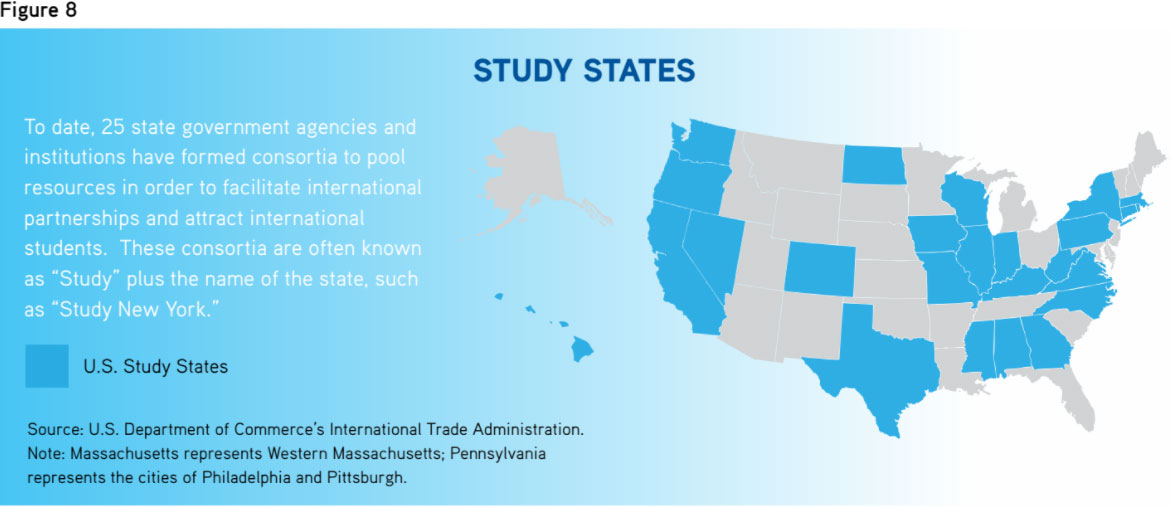

A number of states have also decided to develop their global higher education policy agendas using an organizational model promoted by the United States Commercial Service (USCS), an agency within the U.S. Department of Commerce. USCS estimates education and training to be the fifth-largest services export in the United States, bringing over $22 billion in annual revenue. The “Study [your state]” model was developed by the USCS in order to provide states with a mechanism to pool resources, brand the education sector in each state, and market to students outside of the state, with an emphasis on international students. As of 2013, there were 25 states operating such programs. Two metropolitan-focused consortia have also been established in Philadelphia and Pittsburgh, although there remains no statewide effort in Pennsylvania (see Figure 8 on page 15).

The purpose of these study initiatives is to pool resources of multiple entities to brand the education sector in each state and market to students outside of the state, with an emphasis on attracting and recruiting international students. These programs can be offered in a variety of ways. Maintaining a web presence, including a homepage and a Facebook page, is the most common method, but at times these programs recruit overseas as well. Some programs work to facilitate campus and faculty collaboration as well as to capitalize on opportunities made available by state and federal governments.

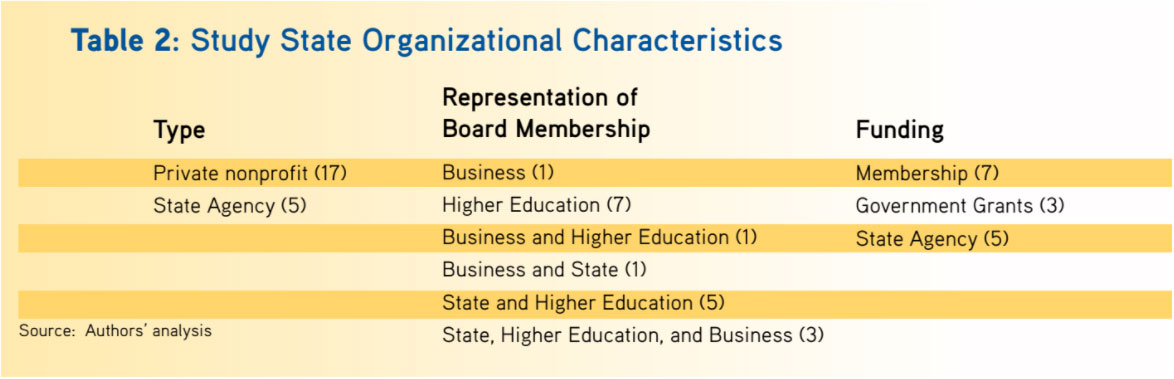

Although the names of these programs are quite similar, they vary from state to state in terms of how they are organized. Table 2 describes the Study State organizational characteristicsby looking at organizational type, board membership affiliation, and funding sources. Of a total of 22 Study State groups, with publicly available information, seventeen are private, nonprofit organizations, usually incorporated as 501(c)(3)s. However, five are located within a state agency, usually the department of higher education or economic development. The members of the programs’ boards or executive offices are also divided among representatives of state government and higher education and business and industry stakeholders. The majority of the Study State groups have higher education representation on the board, either exclusively or in some combination with other executive committees membership from state government or business. Two Study State groups have no higher education representation at all: one group is comprised exclusively of membership from the business community while the other group combines state government and business membership. Funding sources tend to be derived from membership dues. Programs that are located within state agencies are funded publicly, although a handful of nonprofit organizations also receive public funding through government grants.

Most Study State programs are membership based, where the members are dues-paying higher education institutions. They often involve both the public and private sectors, including colleges, universities, and other educational training facilities. To date, most Study State initiatives engage with four-year colleges and universities although there is a growing number— such as Study Maine, Study Iowa, and Study Washington—that include community colleges and high schools. This development reflects a growing trend in the internationalization of community colleges as well as growth strategies for high schools in very rural districts that are looking to offset declining enrollments by recruiting high school students from other countries. Engaging the business community in these efforts is becoming an increasingly common practice of Study State initiatives. The engagement and involvement of commercial interests underscores state-level interest in economic development through internationalization.

Study Maine, for example, was developed by the Maine International Trade Center (MITC), which bills itself as the state’s leading source for business assistance. The Study Pittsburgh! Campaign of the GlobalPittsburgh Education Partnership (GPEP) was formed in 2010 by GlobalPittsburgh, an organization originally created to improve the international competitiveness of the region by developing long-term relationships between cultural, educational, business, and political leaders in the Greater Pittsburgh region and their counterparts around the world. In Colorado, the state’s Office of Economic Development and International Trade worked with the business community to advise on strategy and support the launch of the Study Colorado program.

There is greater variation still in how the consortia are administered. Some programs, such as Study Alabama and Study Virginia, are administered by organizations that promote international higher education. Study New York is coordinated through the Department of Economic Development, which points to the critical intersection between higher education and economic interests. Study Oregon is coordinated out of the Business Oregon office, which is the economic development agency for the state. Study Iowa is similar to Study Maine in its composition but is unique in that it is managed by the Iowa Resource for International Service (IRIS)—a nonprofit organization that also coordinates professional exchange programs and youth development opportunities. Study Iowa is but one initiative organized by IRIS, which brings “students, journalists, business people, educators, and government leaders to Iowa from Africa, Central and Eastern Europe and Asia.”34 Despite their varying structures, these initiatives serve as effective marketing tools for the respective states both to potential students and, in Iowa’s case, investors.

As George Keller once noted, “design [is] better than drift.”35 With this idea in mind, in recent decades higher education institutions and systems have incorporated more formal management practices to guide implementation of their academic missions. For example, strategic or master plans have begun to reflect new internationalization agendas. Reevaluating a formal organizational mission or incorporating new dimensions into a strategic plan represents a complex undertaking in public higher education, given the myriad stakeholders involved: State gubernatorial agendas or other executive agency master plans, accreditation agencies, federal agencies, and regional corporate stakeholders, not to mention local faculty governance, all play active roles in shaping strategic plans.36 Only recently have state- and system-level strategic plans begun to reflect international engagements. In our survey of state-level officials,37 of the 26 respondents, seven affirmed that their strategic plan includes an international education component. Fifteen stated that their strategic plan did not reference international education, while four stated that their state does not currently have a strategic plan for higher education.

These findings are consistent with the results of a previous analysis of 70 economic impact reports written by colleges and universities between 2001 and 2011.38 Higher education institutions produce these reports to provide systematic measurements of their impact on regional and/or state economic activity beyond their core mission of educating the citizenry.

These impact reports became increasingly important after the recessions of the 1980s and 1990s, when cutbacks to state funding for higher education lingered, even once economies bounced back.39 The importance of demonstrating colleges and universities as economic drivers only grew following the great recession of 2008.40 Colleges use these reports to demonstrate the value added to the state by investing in the higher education sector. Looking across these 70 reports, about half mention the importance of international activities, but few provide concrete measurements or evaluations, suggesting that institutions have not focused on measuring/evaluating the impact of their international education activities.

That said, higher education systems across the country are promoting a number of key initiatives to produce more globally savvy graduates. The first is an expansion of study abroad opportunities to ensure that all students who wish to participate in a study abroad program have the opportunity to do so. The Colorado State University (CSU) system, for example, expects that one of every four CSU students will have an international learning experience by 2015, in part through the development of new funding mechanisms for students wishing to study abroad, including creative fundraising initiatives, capital campaigns, and federal grants.

As many college students do not participate in study abroad due to the cost, a commitment to financial support is a key component of such expansion efforts. To its credit, the University System of Georgia now supports five direct aid programs to increase study abroad, exchange, and international internship programs. The Students Abroad with Regents’ Support (STARS) program funds pre-study employment, program assistantships, and travel grants and must be matched by institutional dollars. Georgia residents who have been awarded a HOPE Scholarship, the state merit-based financial aid program, can also apply that funding toward a study abroad experience to help defray the cost.

Recognizing that not all students will have the means or the desire to study overseas, strategic plans consistently encourage member institutions to develop campus-based programs that promote diversity and expose students to foreign cultures, such as incorporating global themes into existing coursework and increasing foreign language offerings. The University of North Carolina’s (UNC) Long Range Plan (2004-2009) not only called for an increase in student participation in study abroad programs but an expansion of coursework and programs that enhance students’ knowledge of the world.42 To facilitate such efforts, each campus in the UNC system has established a unit dedicated to international education and ancillary activities while the UNC General Administration provides coordination and support for all system programs. Similarly, although most international education initiatives in Georgia occur at the campus level, a number of services provided by the University System of Georgia (USG) help to promote institutional efforts to graduate globally conscious students. Such initiatives include increased course offerings, degree programs, and certificates in international fields and strengthened foreign language offerings through a six-year federal grant used to improve technology applications. Fostering cooperation and leveraging resources can be powerful tools for system offices.

Centralized system offices can support institutional efforts by acting as a clearinghouse for best practices and providing expertise to campus-based officers seeking to expand curricular offerings and/or develop campus-wide internationalization programs. The University System of Georgia, for example, assists campuses with admissions and residency policies, visa requirements, faculty development, and risk management and ethics guidelines. System offices can also support the development of international partnerships. Employing such a strategy, the Colorado State University system has begun to develop relationships in four regions and with 20 key institutional partners to create faculty research partnerships that will further globalize the education experience for its students.

Although very few state systems set explicit study abroad goals in their strategic plans, state and system leaders are interested in increasing the flow of students across borders. This interest usually manifests itself as an increase in the promotion and branding of the state’s system of higher education, but some states go even further in developing state-level and system-level student exchange programs. Student exchanges contribute to the internationalization of a college campus and help prepare a globally competitive workforce by providing domestic students with exposure to global cultures. Students representing diverse opinions and backgrounds in the classroom, as well as in co-curricular experiences, can lead to greater intercultural appreciation and understanding among domestic students.

As is often noted, intercultural appreciation goes both ways. International students bring their experiences back home after their studies have ended. Meanwhile, domestic students who study abroad may expand their knowledge of the world and their ability to engage in professional and personal international experiences in the future. Moreover, there is also an economic benefit as foreign students who study in the United States bring in new dollars to local economies in the form of tuition, fees, living expenses, transportation, and entertainment.43 States increasingly leverage the potential of a system approach to encouraging study abroad through coordinating resources across campuses.

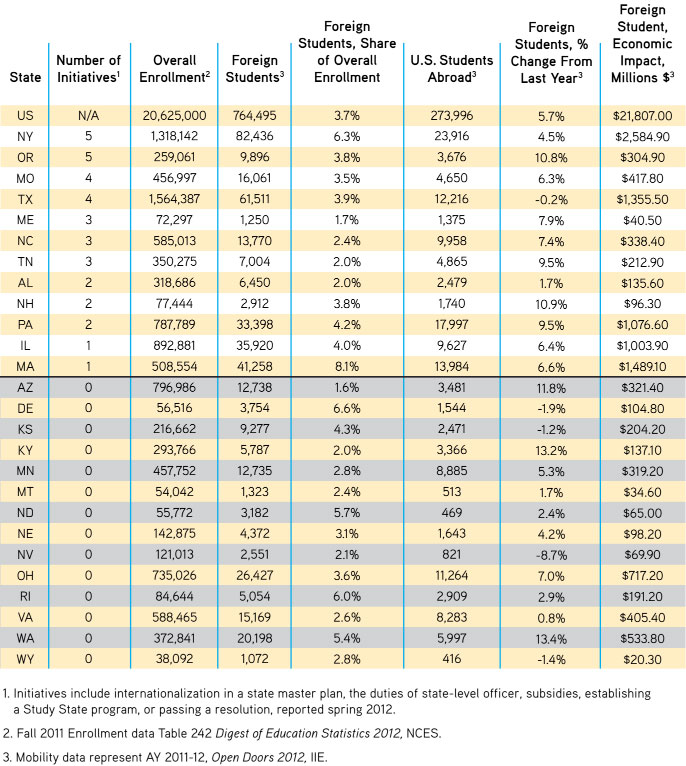

Table 3 provides an overview of higher education internationalization efforts in each of the 26 states that responded to our survey. For each state, we indicate the number of state-level initiatives focused on international higher education that were identified through our survey. This table also lists overall higher education enrollments as well as size and type of student mobility through the colleges and universities in each state. States that report a larger number of internationalization efforts also tend to have larger number of foreign student enrollments, U.S. students abroad, or positive growth in numbers of year-to-year enrollments.

States, primarily through system-level offices, coordinate such internationalization efforts in several ways. The first, and seemingly most common, approach is for state systems to form partnerships with individual institutions abroad. In these instances, a state system develops a formal articulation agreement that allows students studying at any one of a public system’s institutions to attend a foreign institution while paying tuition and fees only to the home campus.

The state of Maine, for example, participates in two major system-level exchange programs:

Partnership Maine-France (PMF) and the George J. Mitchell Peace Scholarship. PMF, which facilitates the exchange of both students and faculty members, is a collaboration between the University of Maine System (UMS) and eight French institutions: University of Angers, University of Maine in Le Mans, University of Nantes, University of Western Brittany, Le Mans Fine Art School, the Teacher Formation Institute for the Lille Region and for the Loire Region, and Theories-Didactique de la Lecture-Ecriture (THÉODILE, an interdisciplinary research group focused on the teaching of reading and writing). The agreement, inked in October 2005, allows students from Maine to study and participate in internship and research opportunities in France and for French students to study in Maine. Outbound students are responsible for tuition charges and mandatory fees at their home institution only and must. provide for their own living, travel, and personal expenses while in their host country. The George J. Mitchell Peace Scholarship is a national student exchange program between the United States and Ireland open to students of both UMS and the Maine Community College System (MCCS). UMS scholarship recipients attend the University College Cork of the National University of Ireland and MCCS students attend the Cork Institute of Technology. The UMS and MCCS each award annually one full-year scholarship or two semester-long scholarships, with recipients being named George J. Mitchell Scholars.

In 2008, Chile and the University of California (UC) system signed an agreement to establish the Chile-California Program on Human Capital Development.45 This program, which builds on a decades-old relationship between Chile and the state of California, provides Chilean students with the opportunity to attend master’s and doctoral programs at any of the campuses within the UC system. The student’s education is paid for by the Chilean Bicentennial Fund for Human Capital Development. The joint agreement also provides a framework for joint research projects between Chilean and UC scholars.

In North Carolina, the UNC Exchange Program (UNCEP) is recognized by the Board of Governors of the University of North Carolina as the official system-wide student exchange program. With relationships in 10 countries and at dozens of colleges and universities, the program also allows students to pay tuition and fees to their home institution, where most federal or state financial aid can be applied. As a multi-institutional exchange program, UNCEP serves as a complement to the bilateral agreements made by individual UNC campuses and allows for semester (including summer), academic year, or calendar year study abroad programs. Since an international student takes the place of the UNC student traveling abroad, domestic students at the home institution also benefit from UNCEP, making these exchange programs a very valuable internationalization effort.

In addition to attracting international students to study at their colleges and universities, some states have created programs that foster research and innovation by recruiting high- skilled immigrants, connecting researchers and companies with international networks, and harnessing university assets to help build relationships with developing nations. In addition to promoting domestic business growth, global initiatives emphasize international cooperation and cross-border partnerships to address economic, health, and environmental issues at home and abroad. Although there may be an educational component to such programs, they are typically oriented toward training business leaders who aspire to trade or provide their services globally.

The Global Michigan Initiative (GMI) is a state-level economic competitiveness strategy that recognizes the significant contributions of immigrants to a state’s economic development and prosperity. Launched in 2011, the GMI is a cooperative effort between the Michigan Department of Civil Rights and the Michigan Economic Development Corporation “to find new ways to encourage more highly educated immigrants and former Michiganders with advanced degrees to come to Michigan to work and live.”46 Despite no formal link to the state’s colleges and universities, the program homepage recognizes the importance of the efforts made by the member institutions of Michigan’s University Research Corridor, which encouraged tech transfer and business startups and the need for highly skilled talent.

Global Washington, by comparison, was formed not to improve the economic condition of the state, but rather focused on efforts in developing nations, providing a perfect platform for internationally oriented initiatives. A membership organization composed of nonprofits, foundations, businesses, academic institutions, and corporations, Global Washington is a catalyst for strengthening the global development sector. Thanks to contributions from parents, educators, and business leaders from across the state, the Global Education Initiative was launched in March 2011 to fill what was considered at the time to be a serious shortcoming in Washington—the lack of a comprehensive commitment to global education.

Following a summit of key stakeholders in November 2011, six recommendations were made to guide the development of a comprehensive approach to global education: (1) build statewide support for global education in grades P-12 and higher education; (2) identify and promote best practices in global education in grades P-12 and higher education; (3) increase second language learning in grades P-12 and higher education; (4) prepare globally competent P-12 teachers; (5) increase global engagement in higher education; and (6) build strong partnerships between global development and global education.

Such ventures need not even be statewide, as is evidenced by GlobalPittsburgh. Established over 50 years ago to promote Pittsburgh-area businesses, GlobalPittsburgh launched the Educational Partnership in an effort to connect more international students with regional businesses, cultural assets, and communities. Through a memorandum of understanding signed in October 2012 between GlobalPittsburgh and the U.S. Department of Commerce, the USCS Pittsburgh office supports the GlobalPittsburgh Education Partnership, a consortium of universities and educational programs, to help increase regional colleges’ and universities’ international exposure.

The California Education and Training Export Consortium (ETEC) is an example of a regional initiative that offers education and training services to international students and professionals. A partnership project between the U.S. Department of Commerce International Trade Administration and the Riverside Community College Center for International Trade Development, the ETEC works with education service providers as well as government and international partners to match the training and education needs of international clients with the right providers; develop nontraditional channels for marketing education services internationally; and provide a network for collaboration among business, education, and government to more successfully respond to international training and education opportunities. The organization also assists members with international marketing of. distinguished and specialty programs by providing assistance in strengthening existing marketing efforts and generating additional word-of-mouth advertising.

This report chronicles the changing relationship between higher education and state governments in the area of internationalization. Historically, states have been ambivalent, if not outright hostile, toward the international engagements of their colleges and universities. However, as governments and economies have become more interconnected, states have had to become more internationally engaged. Indeed, many have already set up offices to help facilitate international trade and attract foreign direct investment. It has been unclear, however, how these growing international efforts have affected the relationship between the state and its colleges and universities.

Public colleges and universities are probably among the most internationally engaged entities funded by a state. These institutions tend to have relationships in dozens of countries. They facilitate a constant flow of student and scholar exchanges, building goodwill between their state and other nations. At times, the reputation of college or university brings new attention to and awareness of the community in which it operates. And, in some cases, these institutions even operate physical locations in foreign countries. It would seem, therefore, that higher education would be a natural partner for states that are looking to expand their international engagements. And, yet, very little is known about state government collaborations with colleges and universities in the area of internationalization.

What we uncovered through this research is that state engagement with higher education in this area is not broad based. Rather, it occurs in four very focused areas: (1) developing an international higher education policy agenda; (2) strategic planning and goal setting; (3) international exchanges and study abroad; and (4) collaborative and innovative research programs. An important—and positive—aspect of these approaches is that the states tend not to provide top-down directives. Instead, they develop a vision, and at times offer resources, to support various initiatives in which institutions can engage if they so choose. In fact, some of the efforts have been approached from the perspective of how the state can support higher education’s work in this area instead of how higher education can support the needs of the state.

Moving forward, states will only become more internationally engaged as their economic success is more and more tied to economic realities outside their borders and those of the United States. To this end, some states are likely to realize the assets that exist within higher education to bolster their international efforts, and there will be increasing questions about what higher education institutions can do to support states in these areas—similar to questions being posed about how colleges and universities can act as economic drivers in the domestic context. With this future in mind, higher education leaders would be well served to begin to consider such engagements so as to guide these coming discussions rather than allow them to be driven by their state leadership.