Federalism During the Obama Administration

Download Report

May 7, 2010

Federalism During the Obama Administration

Thomas L. Gais

Acting Director

Federalism in the Obama Administration

- The federal government during the Obama Administration has been deeply engaged with states, perhaps more so than any time since the 1960s.

- Sometimes it offers states more funding and flexibility; sometimes it seeks to constrain, guide, or direct state policy and budget decisions — generally in service of its views of what domestic policies ought to be.

- This effort to impose central control is nothing new: GWB Administration did much the same, and few recent presidents have treated federalism as something of independent value or an important constraint on their actions.

- Nonetheless, what is striking so far in the Obama Administration is the range of methods and the intensity of its efforts to influence state policies, budgets, and administration.

- Why? Federal officials have little choice:

- They want to shape U.S. domestic policies and their performance

- And, for the most part, it’s the states, and the local governments they oversee, that do U.S. domestic policy.

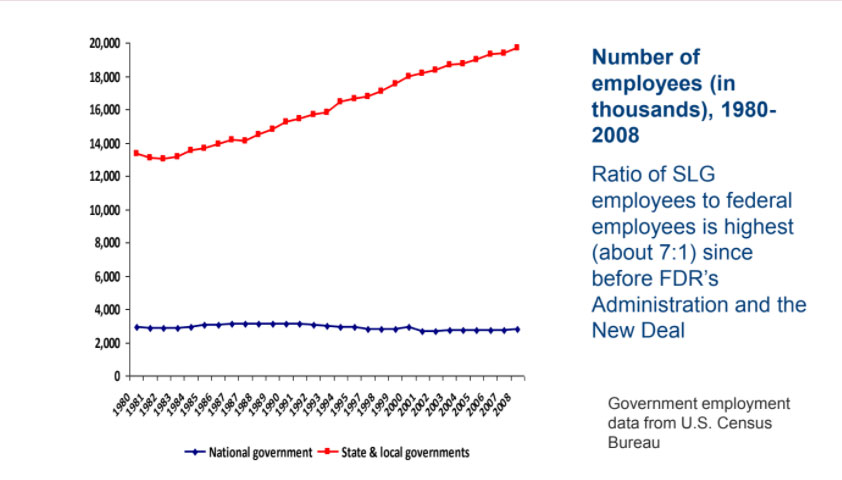

- Role of states in U.S. domestic programs

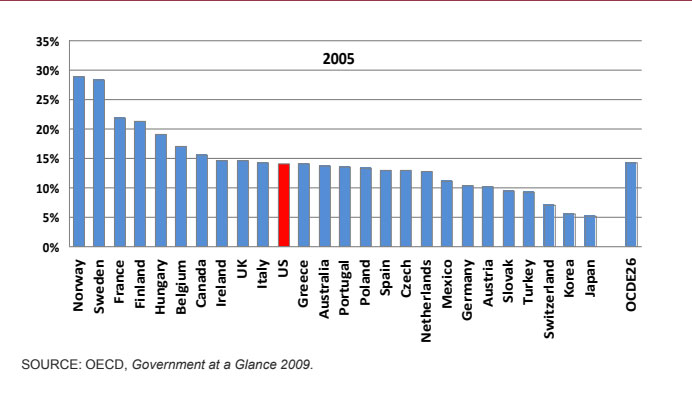

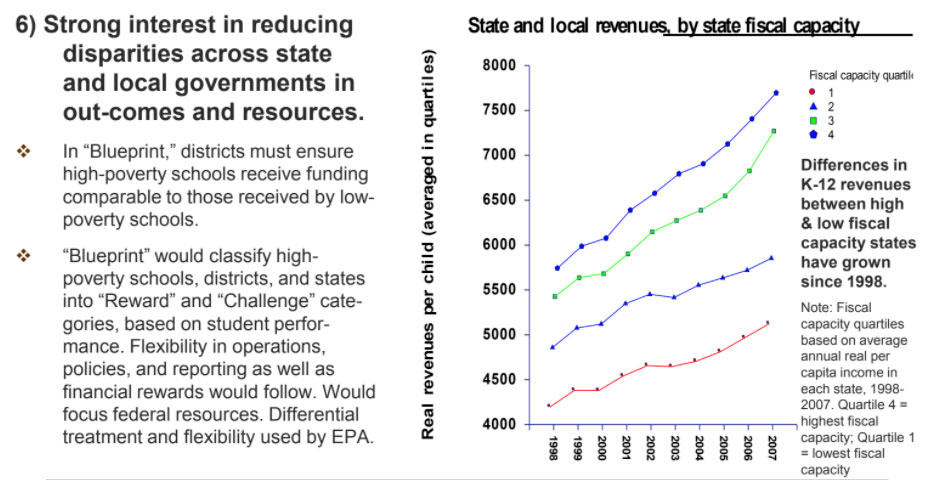

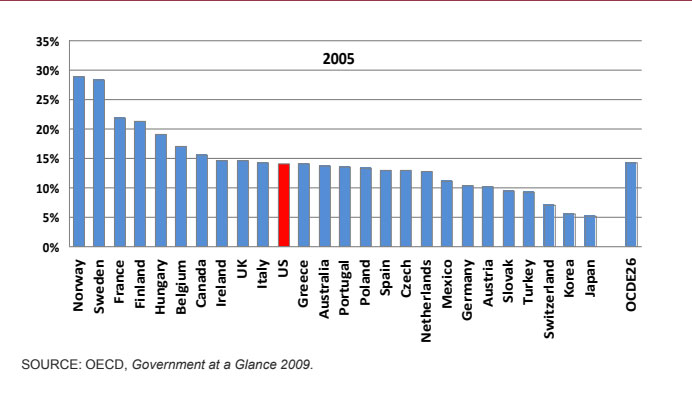

Public employment in U.S. as percentage of labor force is neither high nor low compared to other nations, 2005

What is distinctive is U.S.’s reliance on state and local governments to implement domestic policies

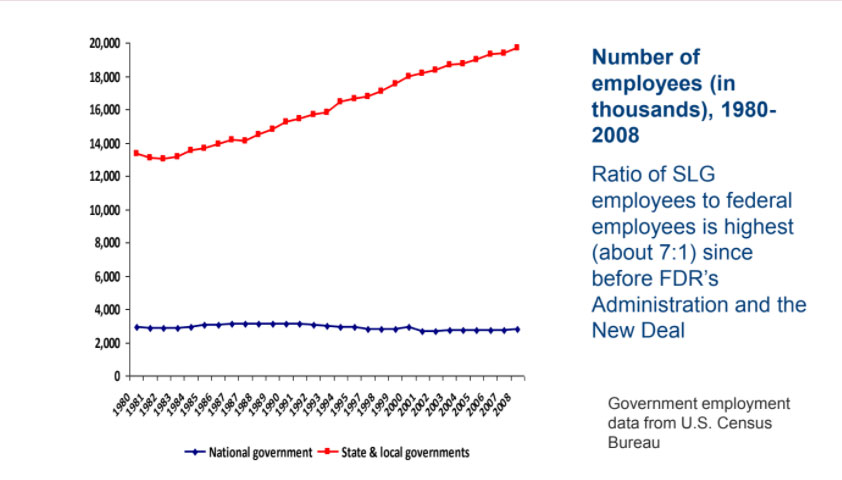

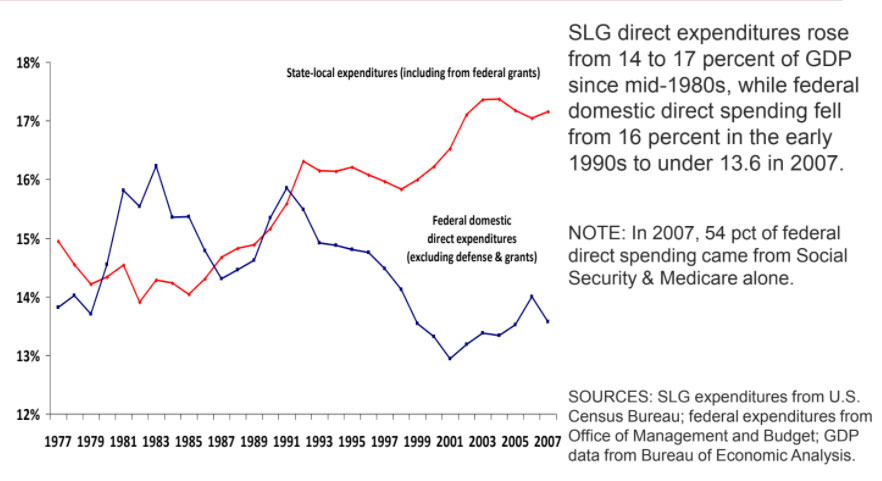

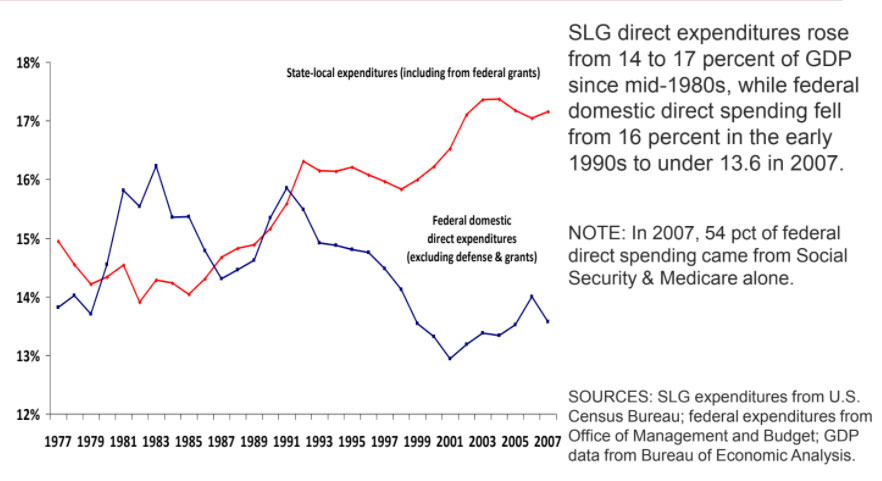

State and local governments spend most of the money supporting domestic programs in the U.S.

Domestic expenditures by different levels of government, 1977 2007

Feature #1 of 2009-10 federalism: Money

- ARRA offered more money to state and local governments than any previous stimulus.

- Of $787 billion in stimulus funds, one-third ($246 b) went to or through states:

- Enhanced Federal Medicaid Assistance Percentage (FMAP): $87 billion

- State Fiscal Stabilization Fund: $54 billion (3 blocks: K-12, $39b; flexible funding, $9b; Race to Top, $5b); $13b, Title I; $13b, Individuals with Disabilities Education Act

- Infrastructure projects: $63 billion, with $28b distributed to states for highways/bridges

- Safety net programs, including Unemployment Insurance, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, Child Care and Development Fund, Workforce Investment Act, Community Services Block Grant, Food Stamps/SNAP, WIC, Head Start, Low Income Home Energy Assistance

- Energy assistance and conservation block grants, state energy grants, weatherization

- Build America Bonds: taxable bonds, subsidized by the federal government, that gave SLGs access to bigger credit markets.

- Contrast with Bush stimulus after 2001-02 recession: Jobs and Growth Act of 2003 included $20 billion in aid to SLGs. Ari Fleisher (2003 quote): “The [President’s] conclusion was transferring tax dollars from … one government to another government was a tax transfer, it did not have a stimulative effect.”

- ARRA emerged from different view: federal assistance to states served multiple goals: economic stimulus + program support + leverage for policy change

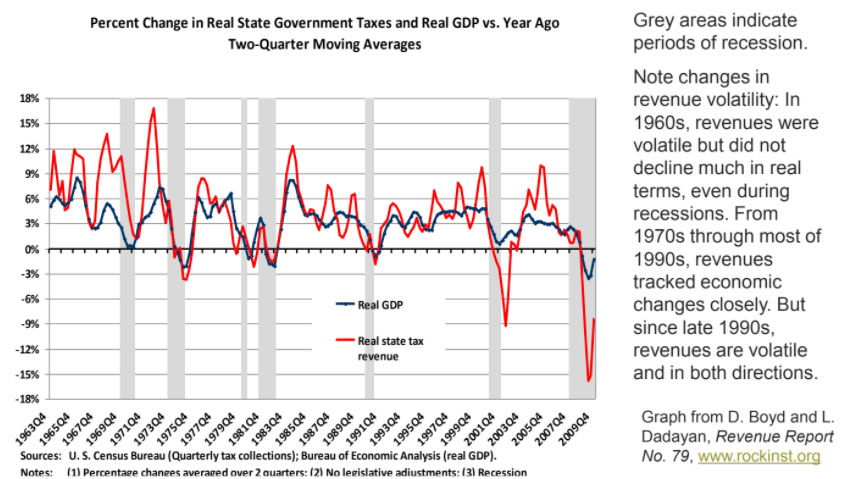

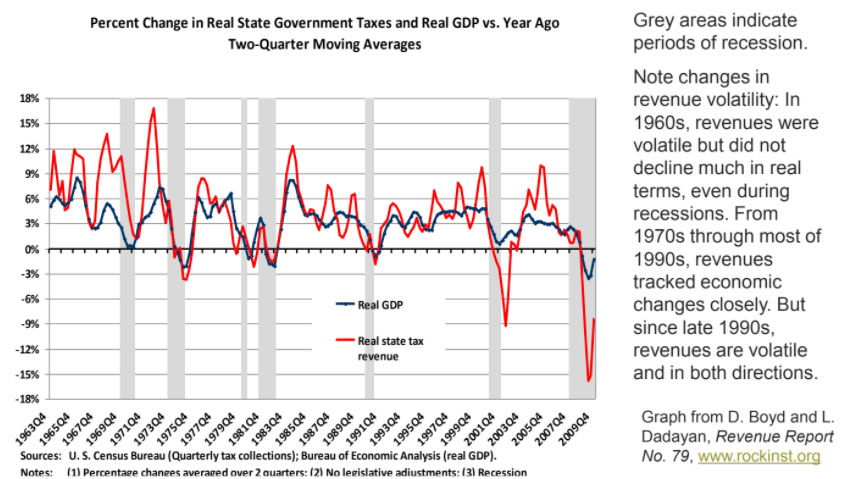

State revenue declines during and after the 2007-09 and the 2001 recessions were both huge

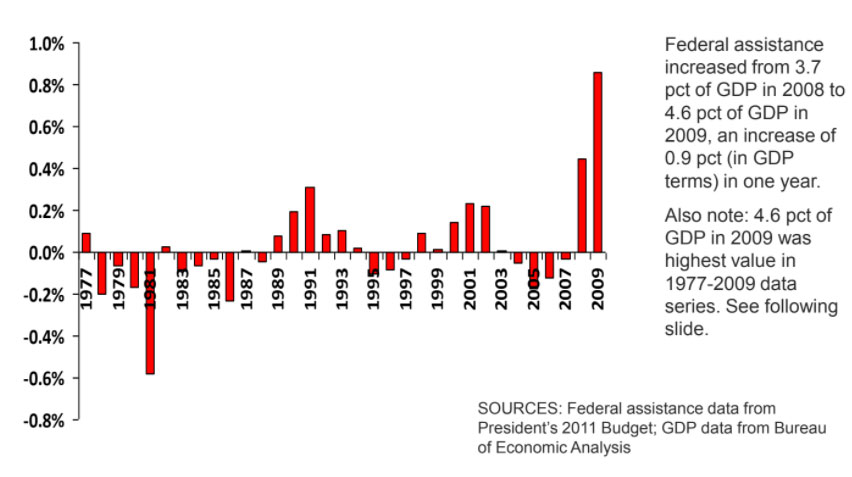

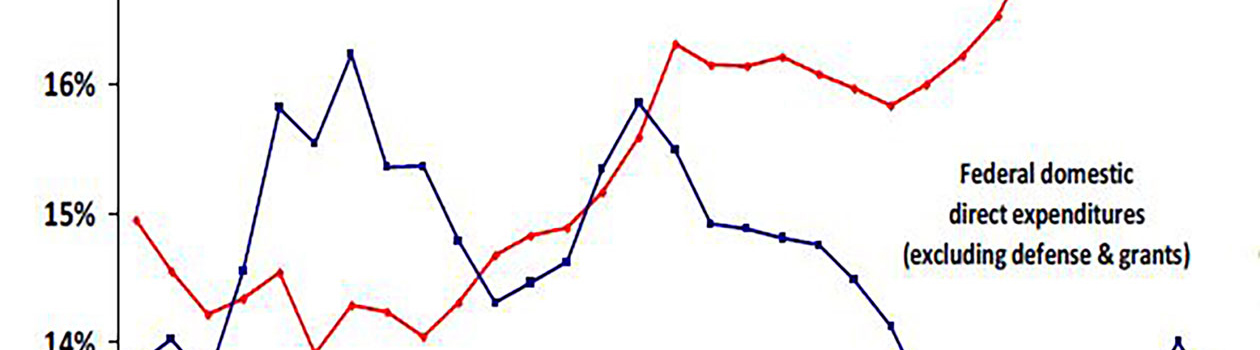

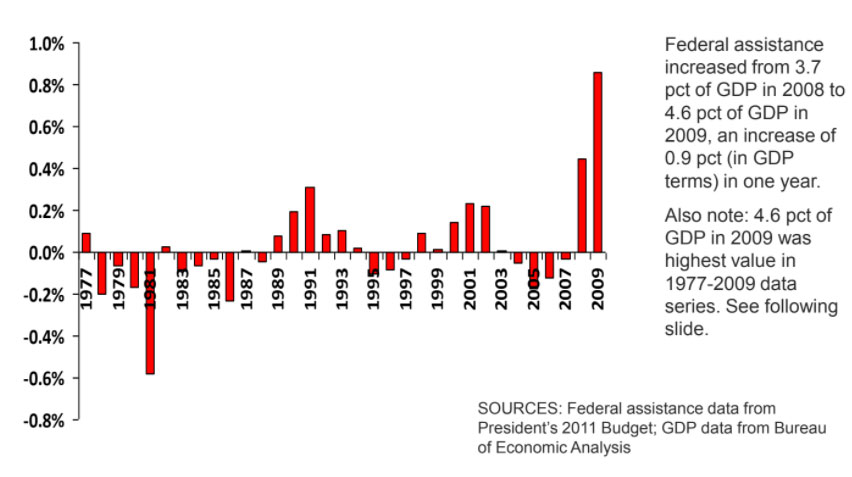

Obama Administration’s response, however, was much larger than prior responses

Annual changes in federal aid to state & local governments (as % of GDP)

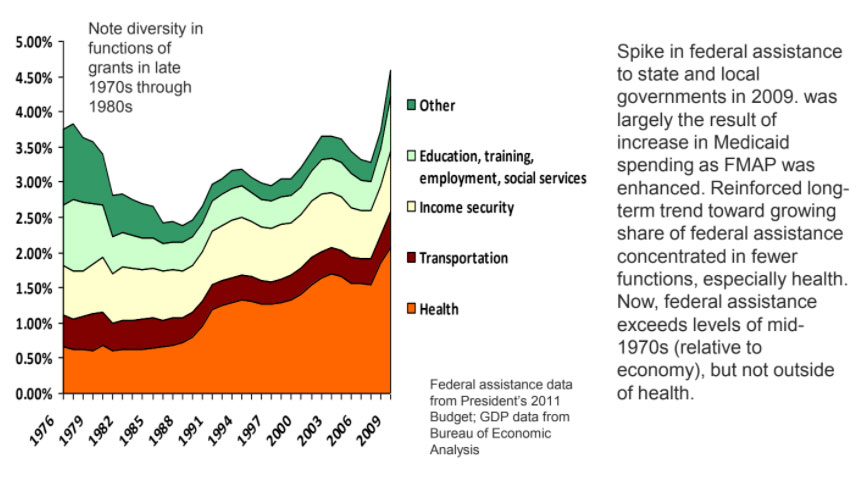

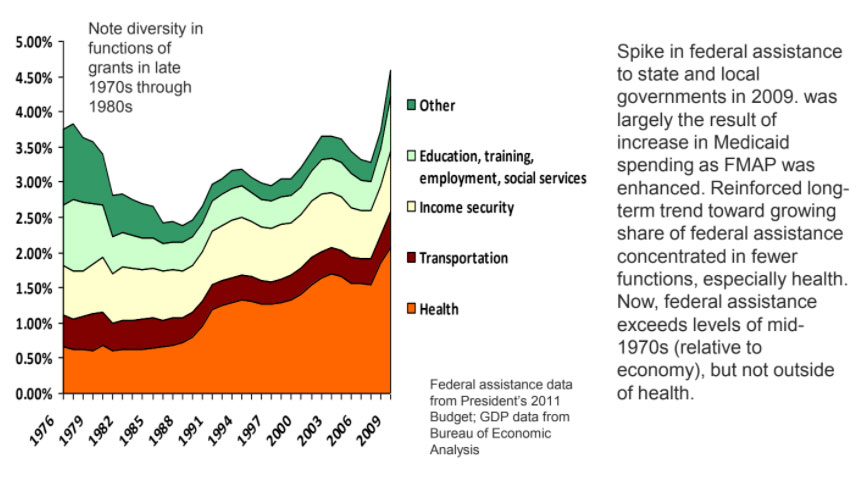

Federal assistance to state/local govts, allocations to different functions, as percent of GDP, 1977-2009

Not just ARRA—more federal has gone (or is expected to go) to states via

- CHIP reauthorization in 2009

- Medicaid and CHIP expansions under federal health reform

- funding for exchanges, high risk pools, many new grants, also under the Affordability Act

- other grant programs under health care reform

- higher education expenditures, e.g., Pell Grants (in the 2010 reconciliation bill)

- research dollars via grants to universities (NIH, NSF, etc.)

- proposals for more grants under Elementary and Secondary Education Act reauthorization (NCLB), based on USDOE’s “Blueprint for Reform”

To whom much is given, much is asked: Other features of federalism under Obama

2) Direct efforts to control state budgets, policies, and administration

- Much of the money comes with strings. Flexibility sometimes offered by feds but usually when states are expected to use it in ways agreeable to Congress and the Administration (e.g., CHIP expansions).

- In many ways, federal assertiveness continues a long-term trend, a trend that intensified under GWB. But this is a different federalism: for one thing, it tries to advance different goals.

- American Recovery & Reinvestment Act

- No state cuts: To receive higher FMAP, state’s Medicaid eligibility must be no more restrictive than it was in 2008; to get fiscal stabilization funds, states had to maintain K-12 and higher ed spending.

- Spend fast: to continue to receive infrastructure funding.

- De-block grants: states were offered extra funding at attractive federal match rate (80%) for additional spending on TANF, but only for cash assistance, diversion payments, subsidized jobs — which had been getting a shrinking or small share of the block grant’s dollars.

- Health care reform: States must maintain current Medicaid/CHIP eligibility levels for children until 2019. States must also maintain current Medicaid eligibility for adults until exchanges are fully operational.

- GWB also sought to shape state budgets but largely to control Medicaid costs & reduce welfare assistance.

Changes in federalism, continued

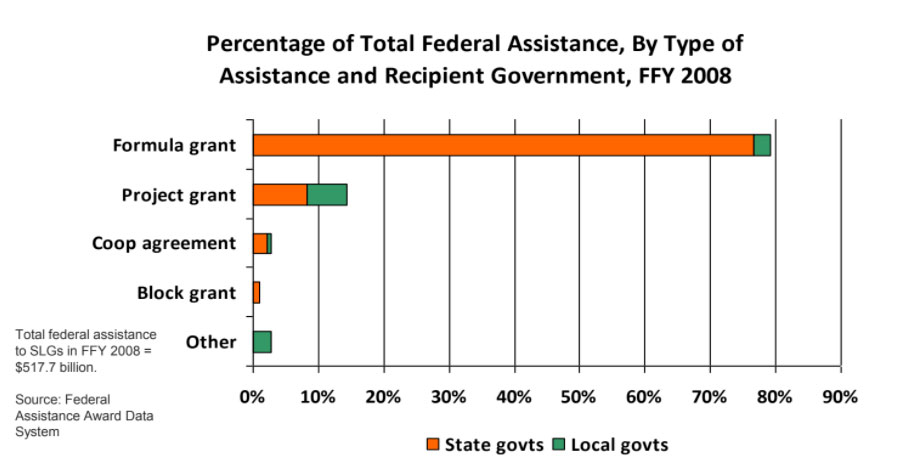

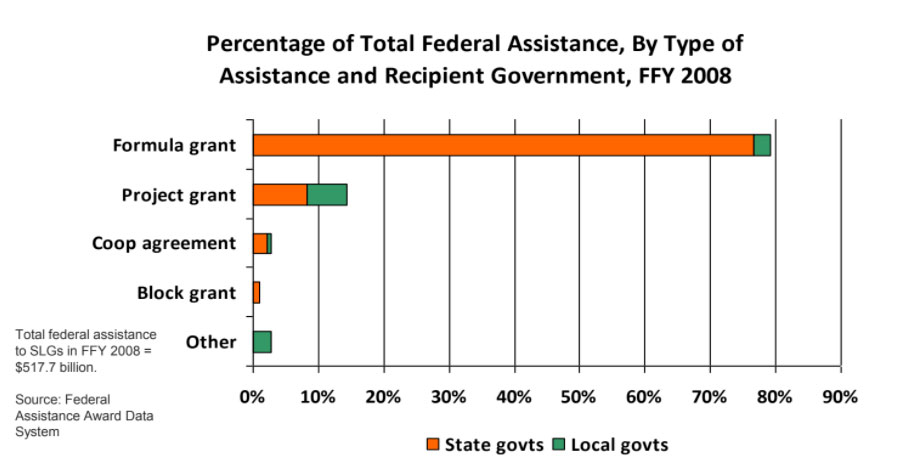

3) Expanded use of project or competitive grants, grants with no pre-determined formula for allocating funds to SL governments.

- Many project grants have been proposed or enacted, with funding for fixed periods and specific projects. Unlike formula grants, which are distributed to governments according to distribution formulas prescribed by law, project grants can give federal agencies great discretion in distributing funds and can be used to influence state policies, budgets, and administration.

- Many such project grants (some are called competitive grants) in the Patient Protection & Affordable Care Act and in proposed changes to Elementary and Secondary Education Act. Some are demonstration projects, aimed at supporting and often evaluating innovative practices of special interest to the federal government.

- “Race to the Top” program in ARRA gave federal government leverage to call for specific policy changes. States changed policies to comply with Administration statements about review criteria: e.g., more charter schools and merit pay for teachers tied to student learning measures—for example, IL, TN, and LA lifted state limits on the number of charter schools

- Project grants on the eve of the Administration were a minority but important part of the grant system (see figure in next slide). But they were most important to local governments. New administration also applies them to states.

- Project (and categorical grants, i.e., formula grants with very specific requirements) also grew during Great Society years in 1960s. But reactions against their inflexibility and distribution followed, including Nixon’s New Federalism, Reagan’s block grants, Clinton’s devolution.

Project/competitive grants were a small but important part of federal assistance to SLGs before Obama Administration; large share went to local governments

Changes in federalism, continued

4) Blurred, entangled, uncertain, and varied division of responsibilities between federal and state governments.

- Hardly new in U.S. federalism, but the Affordable Care Act takes the complexity to a new level.

- Responsibilities of federal and state governments over health careare (and will be) interwoven, interdependent, & varied:

- Federally administered subsidies and state-operated exchanges will affect each other

- Who has what powers and responsibilities over many areas is still unclear: example of private-pay insurance companies and plans new role for feds

- Federal government has authority to take over administration of an exchange if it finds a state to be not compliant; could lead to varied federal and state responsibilities across states (like OSHA); also, high risk pools

- More generally, health reforms include many strong interdependencies between major components: Medicare, Medicaid, employer sponsored insurance, and exchanges. Each of these involves different federal-state balance of responsibilities, but system success depends on their coordination.

Changes in federalism, continued

5) Executive influence

- Trend since Reagan to use growing variety of executive powers to influence states: from waivers to rulemaking, memoranda, demonstration projects, grant conditions. Medicaid has changed many times as result of waivers and other executive decisions. For instance:

- GWB Administration used agency guidelines to limit state coverage of SCHIP in 2007; issued Medicaid regulations in 2007 that limited Medicaid reimbursements; in 2008 permitted Rhode Island unprecedented flexibility to cap costs in its Medicaid program.

- GWB Administration also denied waiver for California’s emissions requirements; but DOE Secretary Spellings issued waivers to alleviate state complaints about NCLB’s inflexibility in 2007-08.

- Faith-based initiative was another executive program; offices set up throughout federal government to reduce barriers at all levels of government for contracts with FBOs

- Obama Administration officials have already used executive powers to advance specific ends

- USDOL guidelines called on states to make big changes in WIA systems (e.g., requiring stronger connections with UI).

- USDOE was particularly assertive in demanding extensive data reporting to document state education reforms under ARRA’s implementation.

- Reversed decisions by GWB Administration: approved California Clean Air Act waiver; reversed “provider conscience” rule.

- Competitive grants in ARRA and Affordability Act give executives considerable influence.

Changes in federalism, continued

Changes in federalism, continued

7) Continues stress on accountability based on measured “results” but with emphasis on evidence-based practices and greater concern about data quality and comparability

- Would change outcomes of interest under ESEA from state-developed tests to more comparable inter-state measures of graduation rates and readiness for postsecondary programs.

- Puts new emphasis on research and diffusion of evidence-based practices — i.e., practices in education and health care that have been evaluated and found to be more effective than others.

- Focus on practices may be move away from devolution’s “loose on means, tight on goals” mantra (e.g., TANF); could lead to greater tightness on means, but means selected on the basis of demonstrations and research.

Summary and explanation

- Centralization (using combination of controls and selective flexibility to advance central government’s views of appropriate policies and budgets).

- But centralization of a different kind: more money, targeted assistance, executive control, federal entanglement in state policies and operations, and interest in using states to identify and diffuse “effective” practices across entire system.

- Strong interest in domestic policy change and program effectiveness.

- State fiscal weakness gives feds more opportunities to push states around.

- Growth in range of intergovernmental tools (including executive powers)

- Not much political support for greatly expanding federal bureaucracy.

- Limits of other direct forms of federal action (e.g., tax expenditures).

Will this assertiveness persist?

- Reasons to say yes: interest in domestic policies and effects will continue; states’ roles will remain central; new laws and powers give feds greater leverage/tools.

- But also reasons to be skeptical:

- Divided national government (possible after 2010) often gives states flexibility (e.g., 1990s; 2007-08): divided govt gives states wider range of opportunities to influence feds, and makes it hard for feds to resolve issues.

- Federal paralysis may be exacerbated by divisiveness of issues remaining on national agenda (immigration, energy, environment).

- Federal efforts to hold states accountable through outcomes and performance measures haven’t worked as expected in the past (NCLB, TANF) — could lead to a partial retreat.

- U.S. politics has not long tolerated focused, highly differentiated treatment of states and localities, for instance, competitive grants that go to a select few. Money likes to be spread around.

- Example of Model Cities (1966): Rapid dilution of idea to focus on 6-8 cities in great need that took planning seriously; funds eventually went to 147 cities in 45 states.

- Federal dollars are tighter

But if it persists, what will be its effects?

- Although federalism under Obama continues prior trend toward centralization, it’s a more challenging task for the current administration than it was, say, for GWB: has positive policy aims; seems serious about policy effectiveness; is interested in policies and results in more states; and willingness to take direct role

- Raises questions

- Can the federal government work effectively with states in such intense, complicated ways? Can federal agencies oversee so many education and health operations? Can they handle direct operations where states fail?

- Can we identify the most effective practices implemented in the federal system? Good research is hard; results often depend on circumstances.

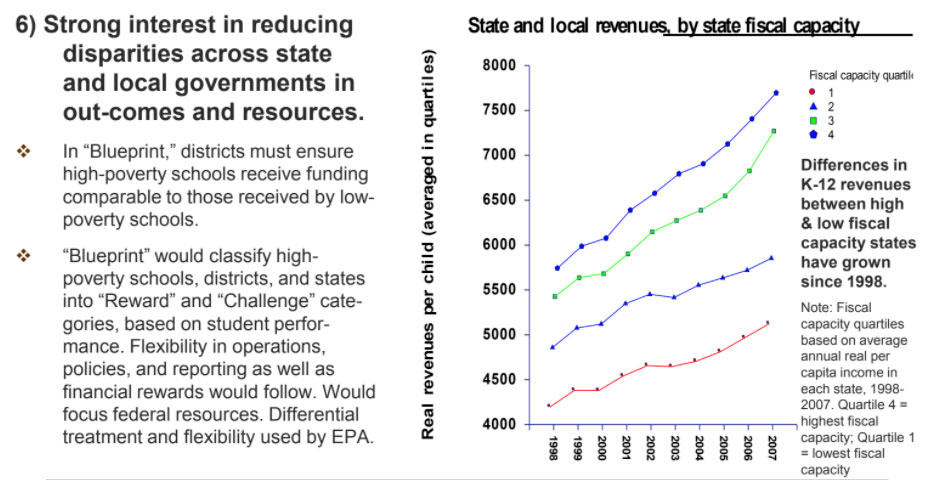

- If such practices are identified, will they spread to other states? In past, the diffusion of policies and practices has been limited by state fiscal capacity and political culture (e.g., limited spread of state EITCs).

- Can policy, budgeting, and capacity differences across states be reduced? Hard to do: financial incentives have not worked in many instances. Many political and fiscal capacity barriers to overcome.

- What will be the effects on state management? Can states manage finances and programs in fragmented, uncertain system (with many project grants and narrowly targeted categorical grants)?

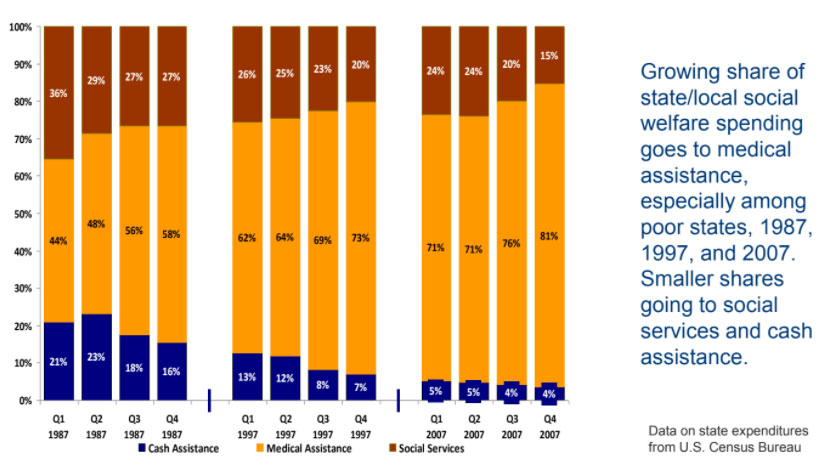

- Will federal priorities squeeze out other state and local functions?

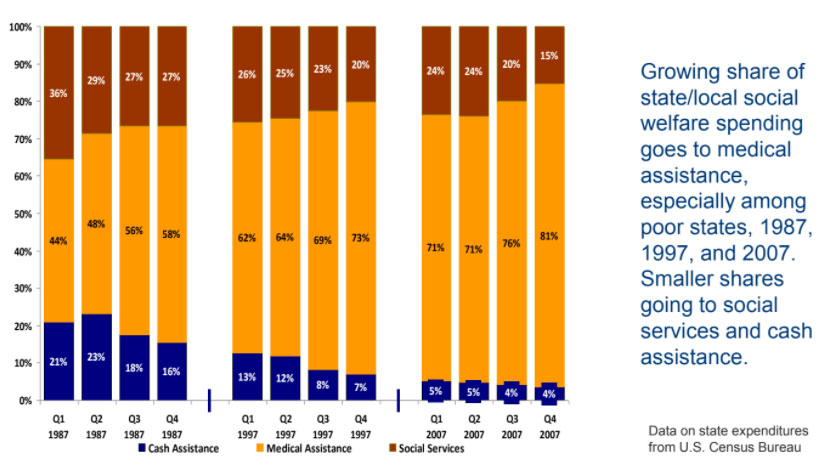

Example of squeeze? Nonhealth social services may have already been pressed by health care spending in recent years. Higher match rate and greater state role in health care may lead to even higher budget priority for medical assistance.

What would it take to ensure that this assertive federalism will work?

- What’s needed to advance national purposes among SLGs while minimizing unwanted side effects, such as budget distortions, escalating federal controls, & greater state variation?

- Not sure there is a good answer, but some measures may improve situation:

- State/federal revenue reforms: ensure that all states have general support for basic SLG programs, e.g., VAT and general revenue sharing; more stable revenue streams for states may reduce squeeze effects and states’ incentives to supplant federal dollars.

- Stronger informational exchanges between federal and state governments: federal regional offices have sometimes been analytically weak and unable to provide clear picture of the situation in states; more generally, capacity of federal agencies to use and analyze data already collected could be strengthened

- More systematic research on the effects of different intergovernmental methods: we evaluate programs administered by state and local governments; but we do not place comparable priority on assessing the effects of mechanisms for funding, incentivizing, regulating, and overseeing the implementation of such programs in the federal system

- What will happen when federal money runs out?