July 2017

Several years ago, because of the Great Recession, teachers faced a weak job market — where even hard-to-fill spots, like special education, were getting hundreds of applications to fill a couple of openings. There were reports that nearly every graduate from certain education programs found themselves jobless upon graduation. However, due to economic growth, retirements, and other factors, recent studies suggest that there is a pending large-scale teacher shortage nationally. More detailed data collection and analysis must be done to determine whether there will be a large impending teacher shortage on the nation’s horizon. The current data show historic shortages in areas such as special education and math, and in certain geographic locations, like rural and inner city urban communities. Notwithstanding long-standing difficulties in recruiting in many school districts, an understanding of the problem remains elusive on a more micro school-by-school level. As teacher labor markets are often “local,” shortages in some regions co-occur with surpluses in others.

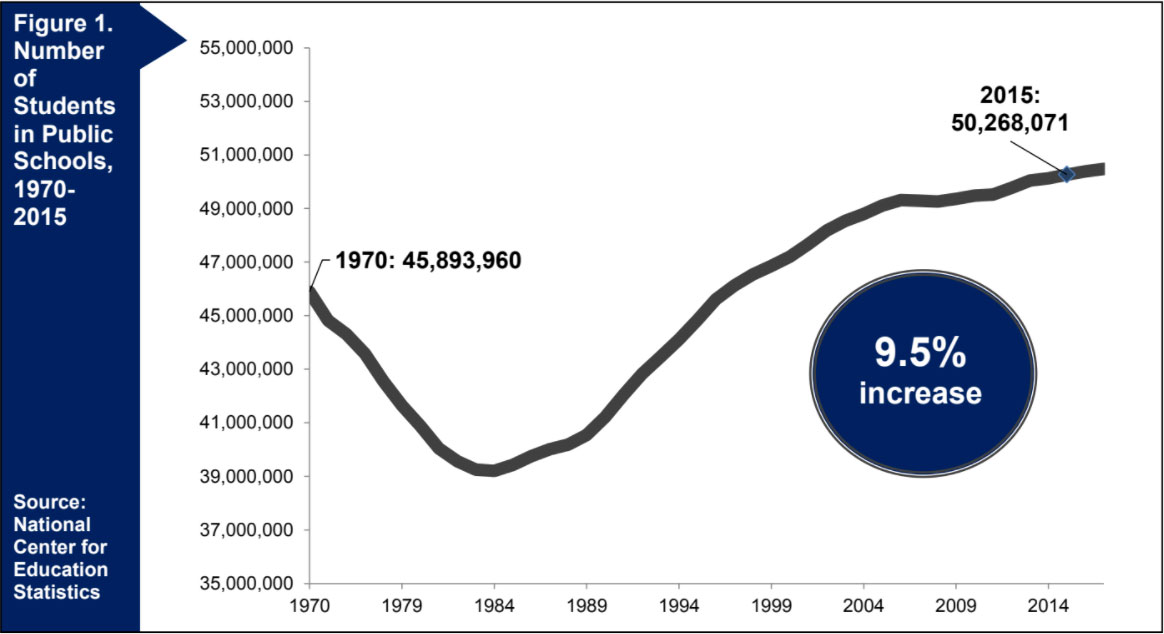

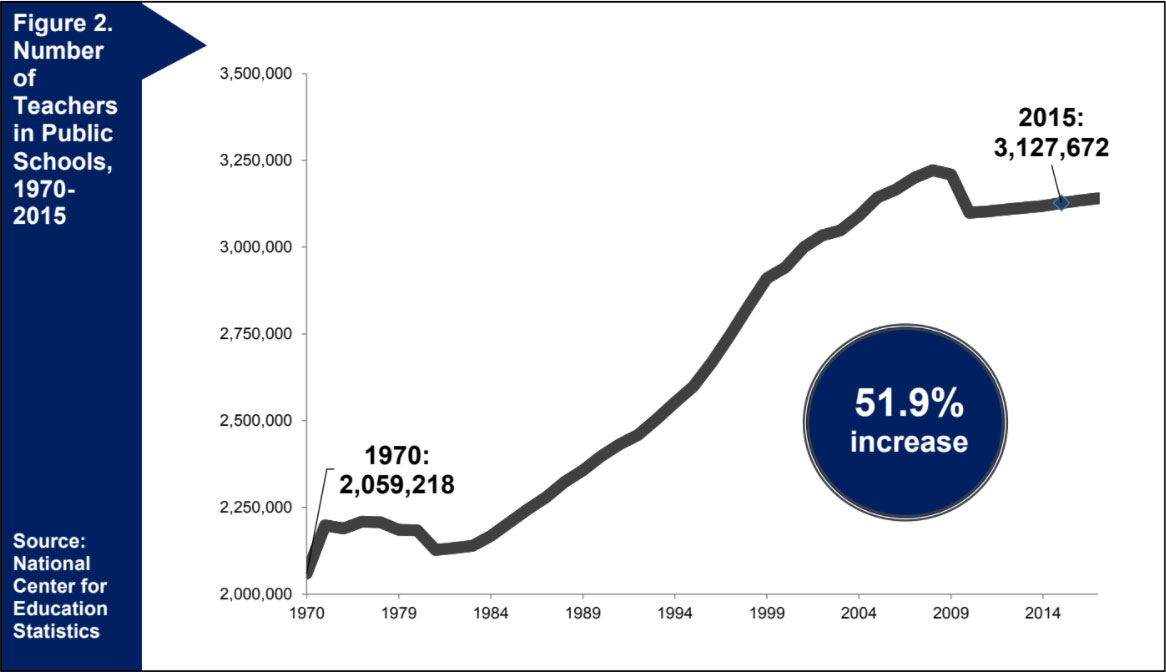

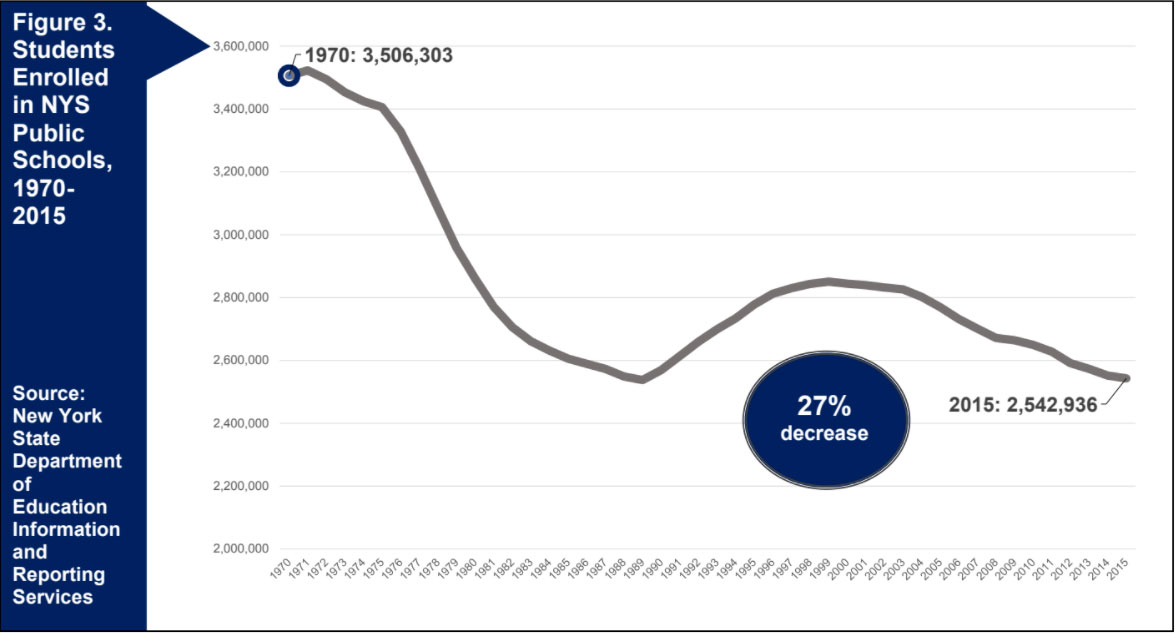

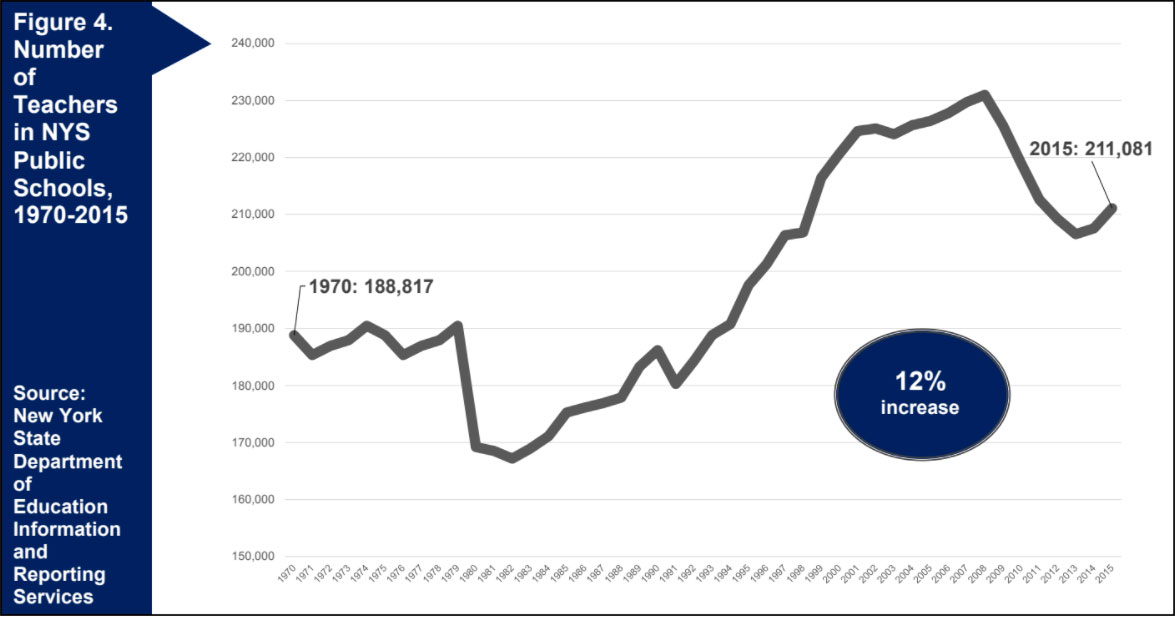

Nationally, since 1970 the number of teachers has increased 51.9 percent, while the number of students has increased 9.5 percent. In 1970, the student/teacher ratio was 22.3 and it is significantly lower at 16.1 today. New York shows somewhat different trends, as the number of teachers has grown nearly 12 percent, while the number of students in the classroom has declined nearly 27 percent. Together, these trends resulted in a dramatic decrease of the student/teacher ratio, from 18.57 in 1970 to 12.05 in 2015.

Yet, this only tells part of the story. Although there are projections indicating an increased demand for teachers going forward, the overall projections don’t necessarily create a supply issue across the board. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) has projected that elementary school and high school teacher employment will grow 6 percent, which is just under the average of 7 percent for all occupations. Even though the BLS expects a significant number of teachers to retire, “many areas of the country already have a surplus of teachers who are trained to teach kindergarten and elementary school, making it difficult for new teachers to find jobs.” The BLS does note that there are regional opportunities, like in urban and rural schools, as well as subject matter needs like math, science, and special education. Further illustrating the local nature of teacher labor markets, 65 percent of first-year teachers entering the New York public school system worked in schools less than fifteen miles from where they attended high school. Eighty-five percent of new teachers were employed in schools less than forty miles from where they attended high school.

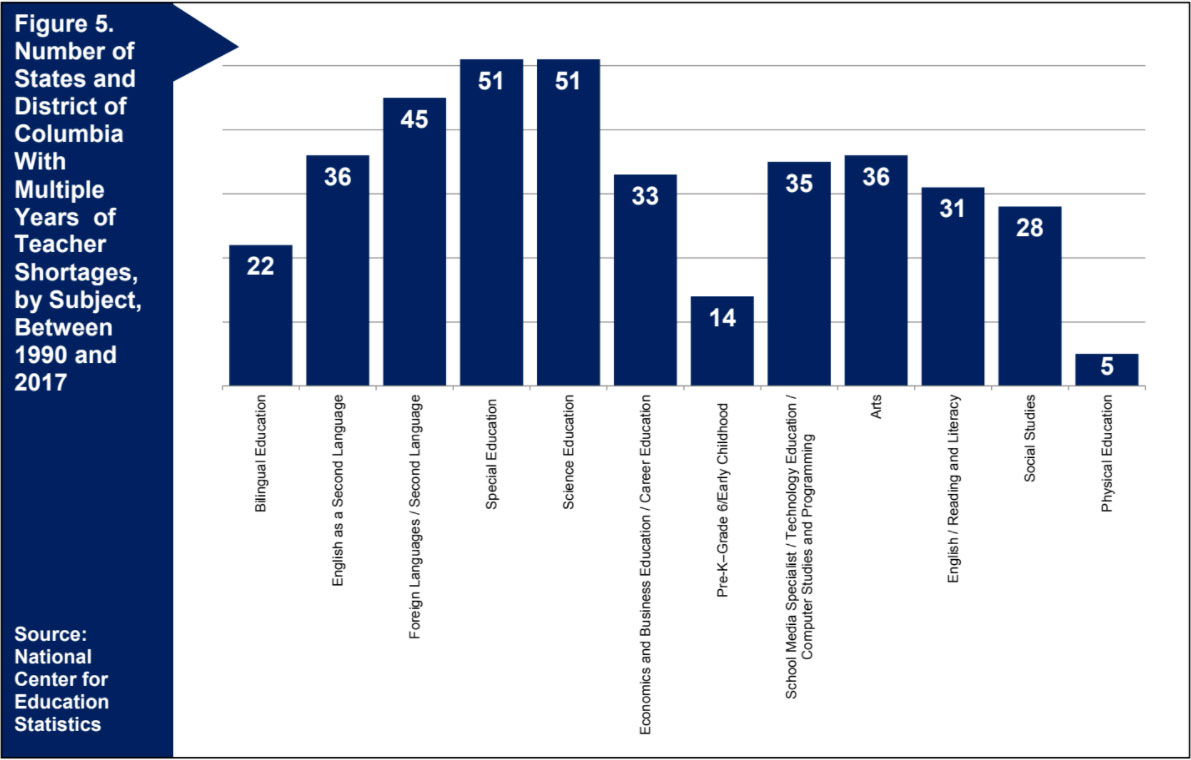

Examining National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) data from 1990 shows there are annual shortages in certain subject matter areas such as special education, science, and English as a second language. As Figure 5 illustrates, virtually every state has districts with shortages in those areas.

Although overall employment growth in education is nearly the average for all industries, there remain areas of persistent shortages in schools. In New York, for instance, persistent staffing problems have been in low-income and minority communities, like the city of Yonkers and in New York City. Low pay and job difficulty have been issues raised as reasons why educators shy away from certain jobs in these geographic and subject matter areas. This, however, needs more analysis. Average pay, for instance, may not be the driving factor. In fact, in looking at median salaries in some New York counties, the median pay is higher in the districts with persistent shortages as opposed to those without teaching shortages. For example, the Southern Tier region in New York State has been identified by the NCES as have persistent teacher shortages. Yet, the median salary in this region is higher than other regions of the state. Rather than average pay, entry-level salaries may carry greater weight in attracting more (and perhaps better) recruits into teaching positions.5 But analyzing that impact requires deeper analysis and more data on teacher careers.

Though recent employment trends are beginning to shift, with the onset of the Great Recession in 2009, the demand for teachers in many traditional areas — elementary education and nonscience/math secondary subjects — was less robust, a trend that was especially apparent in the Northeast and Midwest, regions with little growth in the school-age population. At the time, with pervasive sharp declines in state revenues, one of the sectors to feel the greatest impact was education, since the loss of state revenue could only be partially recovered at local levels by increasing property taxes. Consequently, roughly 300,000 teachers and other school employees lost their jobs, and tens of thousands of others graduated from colleges and universities to face one of the worst job markets in recent history. This situation, in turn, had an impact on educator-preparation enrollments, with the largest declines seen in key provider states, including California, New York, and Texas. Most educator-preparation programs in New York State and across the country experienced unprecedented levels of declining enrollment over the past decade, a trend some believe partly owe to a shifting economy, which opened up opportunities in other sectors to accompany a general stagnation in the numbers of students entering higher education (particularly in the Northeast), recent reductions in hiring at the P-12 level due to budget constraints, and a decline in the attractiveness of the teaching profession. In the near term, these lower enrollments could result in decreased funding for programs at the campus level, along with reductions in faculty, instructional materials, and facilities, which could have a long-term impact on institutions’ ability to meet future demand.

In addition, a number of studies have argued that students enrolled in educator preparation programs, especially those seeking certification as elementary teachers, are less academically skilled when compared to other groups of students; that on averagethey score lower than other students on standardized tests.6 This issue also received more public attention when the National Council on Teacher Quality issued its latest in a series of controversial reports critical of teacher-educator programs, charging that too many programs fail to recruit the best students. By comparison, nations such as Finland and Singapore have made recruiting teachers from the top ranks of their classes a matter of national policy, and in the past two decades they have achieved remarkable outcomes in student learning. In response to calls to raise the bar for entry into educator preparation programs, the 2015 expectations of the Council for Accreditation of Educator Preparation specify an overall 3.0 GPA for entering cohorts, and states like New York have created policies to do the same.

Some alternative teacher preparation programs — such as Teach for America, New York City Teaching Fellows, and Urban Teaching Residency — may offer useful ideas for recruiting promising teachers in hard-to-serve communities. Such programs actively recruit candidates, sometimes with a focus on finding people with ties to the target community; they appeal to the potential teachers’ idealism; they offer short-run benefits, such as rapid employment, tuition support, and stipends; and they offer prestige and a supportive peer group.7 Testing the effects of these and other approaches to recruitment into hard-to-serve schools and districts should be a priority.

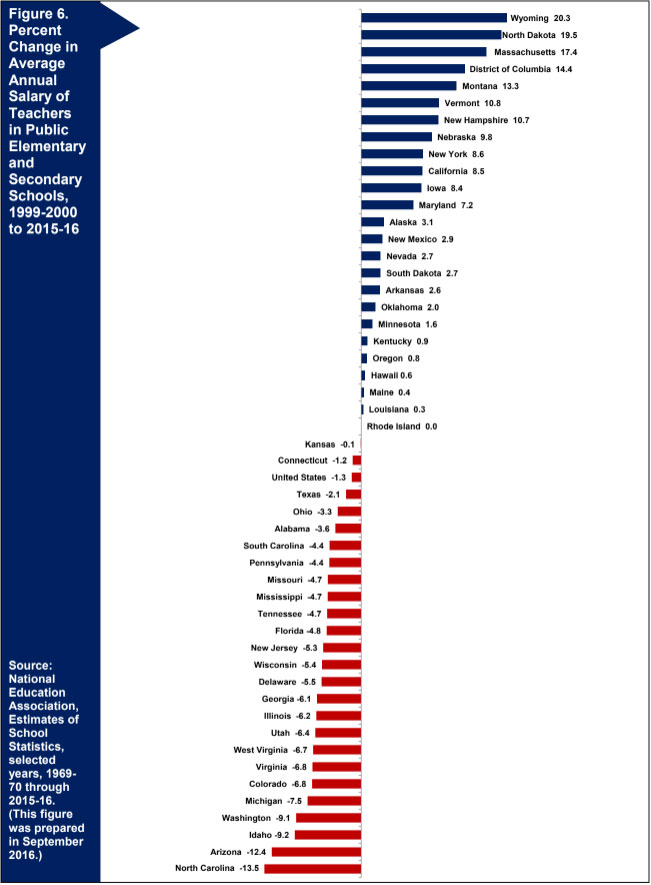

Since 1999, average annual salaries have decreased 1.3 percent nationwide. As Figure 6 illustrates, there is great variation among states, suggesting there are other issues at play depending on the region. The effect of wage differentials must be examined more closely, yet suggests there could be issues with staffing in certain parts of the country.

What also needs further analysis is whether public perception of the profession is driving some of the problems recruiting and retaining educators. As was found in the comprehensive report on the teaching profession in New York, under the TeachNY program, “Educators face ever-increasing scrutiny from a range of stakeholders, perhaps most notably politicians, who make essential funding decisions and who have loudly held public school teachers solely responsible for the documented ‘failures’ of U.S. schools.”8 Though recent public opinion polls show strong public support for educators, the perceived public “demonization” of the teaching profession could be hurting recruitment and retention efforts in the field.

Any examination of the teacher pipeline, as well as solutions to the persistent shortage and subject matter areas, should examine the role educator and public perception play in altering the education workforce.

Overall, data show that turnover in the education profession is less than in other industries. A recent Aspen Institute study, using data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, found that 24 percent of educators left their job, compared to 41 percent in all professions.

In addition, per NCES data, 84 percent of educators remain at the same school, 8 percent move to a different school, and 8 percent left the profession during the following year. Of the teachers that left the profession, more than 50 percent stated their workload in their current position was more favorable than teaching. However, certain districts, specifically those less affluent, had more difficulty retaining teachers. We would more fully explore this and tailor solutions to this more nuanced problem.

Novice teachers benefit from support, especially in the early years of their careers. They frequently report feeling isolated, without supportive partners, at times working within a school environment that is more competitive than cooperative. The literature reveals that novice teachers often decide to leave the profession because of some key school-level factors: low pay, lack of support from school leaders, problems with student discipline and motivation, and lack of professional autonomy. Studies indicate that roughly 40 percent of novice teachers leave the classroom within the first five years. The statistics are even more troubling in high-poverty schools, where attrition rates are roughly 50 percent higher compared to wealthier schools.

State and local school leaders can address many of these factors through thoughtful reforms in school leadership, school culture, teaching and learning conditions, and mentoring and induction programs. Continuing professional support and development not only keeps teachers in the classroom, it has a positive impact on student success. In a comprehensive meta-analysis of over 50,000 studies, researchers concluded that professional development for teachers ranked among the top twenty most influential factors in determining student success.