March 22, 2019

Following the February 14, 2018, shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, FL, which left 17 students and teachers dead and 17 others wounded, there was a renewed call to ban assault-style rifles like the one that had been used in the attack. Public support for such restrictions reached its highest level in more than seven years,[1] prompted not only by Parkland but likely in part by two other high-profile and particularly lethal shootings in the 16 months prior: the Route 91 concert in Las Vegas, which left 58 people dead and more than 400 injured by gunfire,[2] and the First Baptist Church in Sutherland Springs, TX, where 26 people were killed and 20 others were wounded. As with Parkland, the perpetrators in both the Las Vegas and Sutherland Springs shootings also used assault-style rifles.[3]

After the Parkland shooting, nearly 70 new gun control measures were passed in the states by the end of that year (2018), yet none instituted a new ban on assault weapons.[4] Similarly, little action was taken on the issue as a whole at the federal level.[5] At present, there is no federal assault weapons ban, although seven states — California, Connecticut, Hawaii, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and New York, as well as Washington, DC — have a ban in place, and two additional states (Minnesota and Virginia) regulate the sale and possession of assault-style weapons.[6]

As demonstrated in our recent report, Can Mass Shootings be Stopped?, a popular misconception about mass shootings is that assault-style rifles are the preferred weapon of choice for mass shooters.[7] Over the past 50 years, handguns were used considerably more frequently than rifles. Of the 340 mass shootings between 1966 and 2016, at least one handgun was used in 76 percent of events, compared to less than 30 percent of events that involved any rifle, not just those categorized as assault-style.[8]

Assault-style rifles in particular were present in 67 of the 340 shootings (20 percent). An assault-style weapon was present in 69 percent of cases where at least one rifle was used.[9] The remaining shootings involved rifles that had bolt-, lever-, or pump-action firing mechanisms, which require the user to perform some type of action to release the spent cartridge and move a new cartridge into the chamber before the weapon can be fired again.[10] Semiautomatic firing mechanisms, like the ones used on assault-style rifles, autoload a new cartridge into the chamber after the gun is discharged, and users then only need to pull the trigger to fire the gun, eliminating additional steps between rounds and speeding up the rapidness of shooting.[11] These autoload mechanisms are not unique to rifles, however, as both semiautomatic handguns and shotguns can incorporate the same technology.[12]

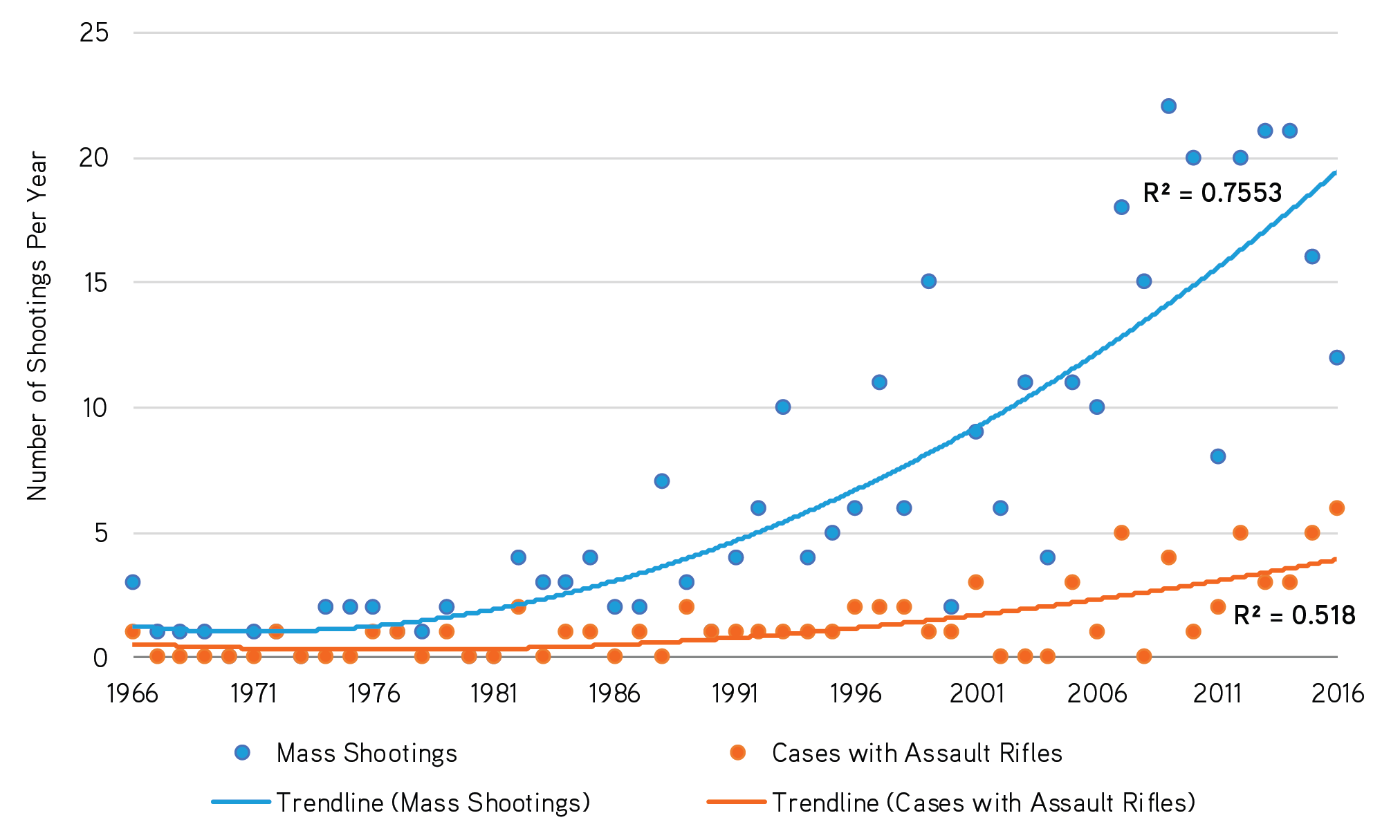

Mass shootings generally have been increasing steadily each year over the 50 years examined (see Figure 1).[13] The greatest number of mass shootings in a single year (22) occurred in 2009, and five years in the six-year period from 2009 to 2014 saw 20 or more attacks each year. Moreover, the use of assault-style rifles has been increasing. As Figure 1 illustrates, however, while the number of shootings involving an assault-style rifle continues to gradually increase, it does so at a rate significantly slower than the average annual growth in the number of mass shooting events. Even so, some interesting data points emerge. In 14 different years, no assault-style rifles were used in mass shootings.[14] In 2016, in contrast, assault-style rifles were used in half — six of 12 — of all mass shootings.

FIGURE 1. Distribution of Mass Shootings and Cases with Assault Rifles by Year

SOURCE: Data for all figures compiled by the author. See also, Jaclyn Schildkraut and H. Jaymi Elsass. Mass Shootings: Media, Myths, and Realities (Santa Barbara: Praeger, 2016).

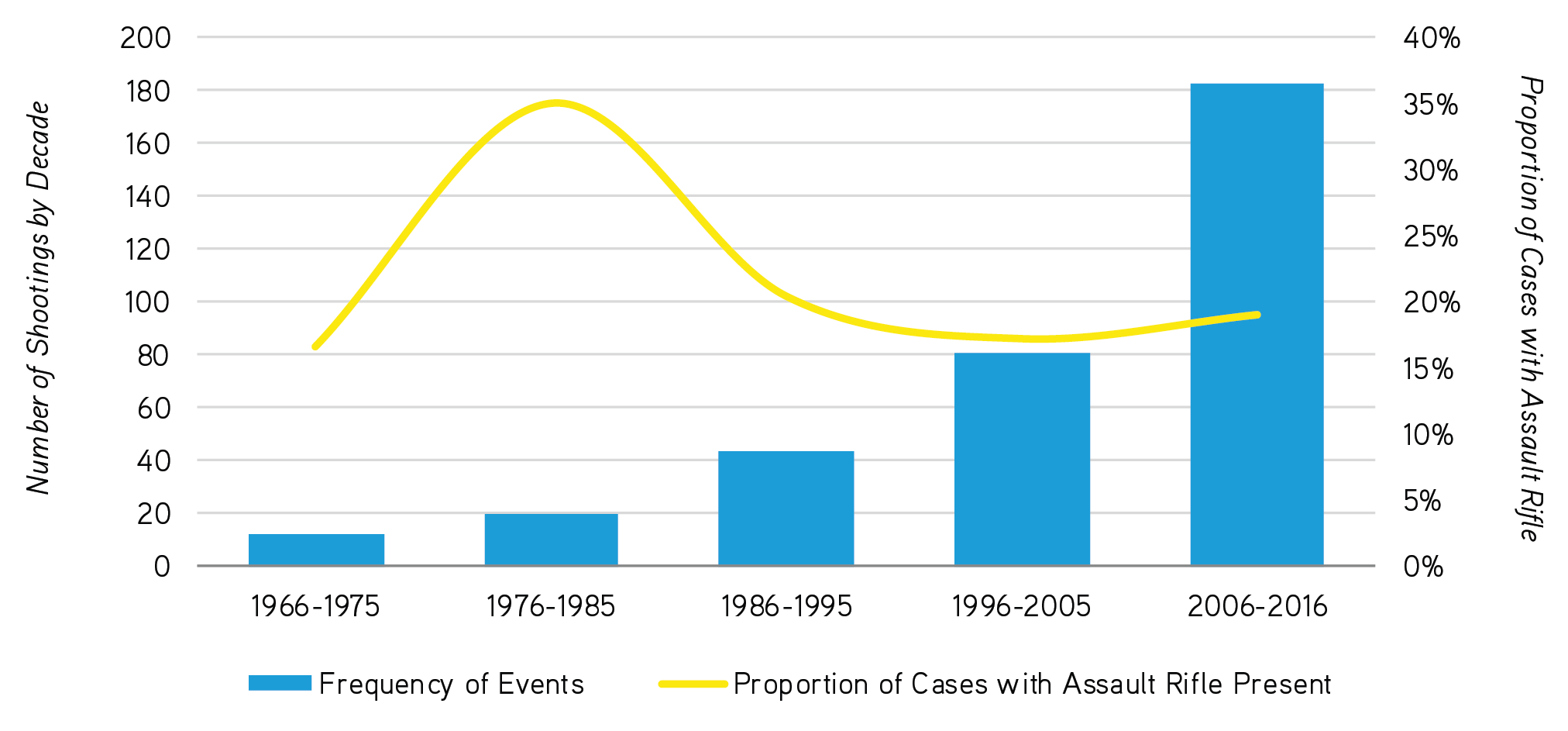

Examining the frequency of mass shootings by decade and the proportion of events in which at least one assault-style rifle was present, the continued increase of mass shooting events is evident. Figure 2 shows that even with such growth in numbers, however, the proportion of incidents involving assault-style rifles has remained largely stable for the past three decades. Considering the presence of these weapons as a function of the number of events per year provides important context that counters claims from some that the use of such weapons is increasing in frequency.

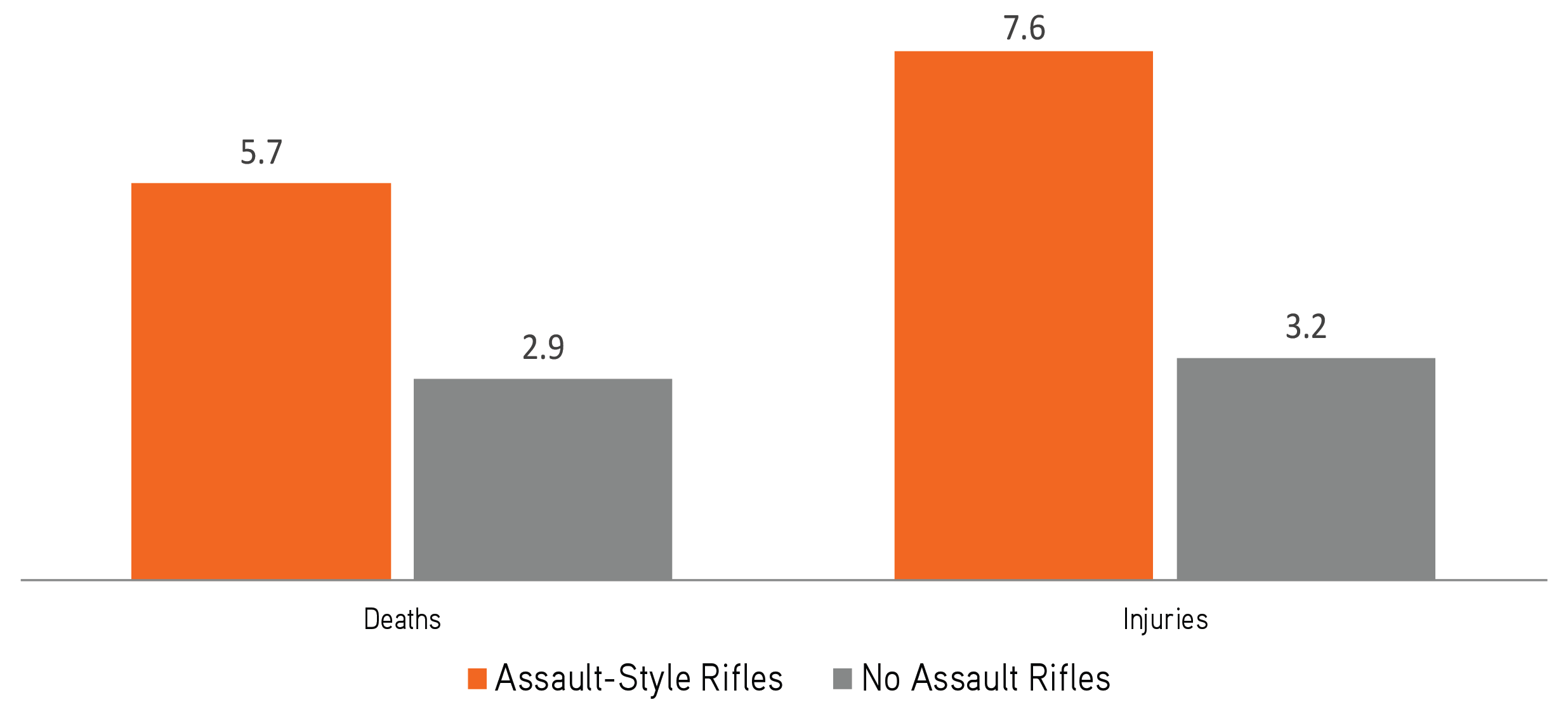

It is not just the frequency of the use of the weapons that should be examined, but also the deadliness of attacks with different weapons. Between 1966 and 2016, 340 mass shootings claimed the lives of 1,141 individuals and left 1,385 others injured.[15] When disaggregating these events based on whether an assault-style rifle was present, a statistically significant difference is found: the presence of these weapons in a mass shooting incident is, on average, correlated with deadlier events. In the 67 shootings involving an assault-style rifle, 351 people were killed and another 511 were wounded by gunfire. Comparatively, in 271 shootings where no such rifle was present, 787 fatalities occurred and 869 people were injured.[16] On average, there were 5.2 deaths and 7.6 injuries in mass shooting incidents involving an assault-style rifle; in comparison, on average, there were 2.9 deaths and 3.2 injuries per incident where no such rifle was used (see Figure 3).

When disaggregating these events based on whether an assault-style rifle was present, a statistically significant difference is found: the presence of these weapons in a mass shooting incident is, on average, correlated with deadlier events. In the 67 shootings involving an assault-style rifle, 351 people were killed and another 511 were wounded by gunfire.

The most lethal shooting — the 2016 attack at Pulse Nightclub in Orlando, FL, which claimed the lives of 49 people and left 53 others injured — was committed with an assault-style rifle. That is not to say, however, that mass shootings using other types of firearms are not highly lethal. The 2007 mass shooting at Virginia Tech in Blacksburg, VA, provides an important example: using two semiautomatic pistols (a Glock 19 and a Walther P22), the perpetrator shot and killed 32 people and wounded 23 others before committing suicide. Variations of the Glock pistol also were used in a number of other mass shootings including, but certainly not limited to: a Killeen, TX, restaurant in 1991 (23 killed, 20 injured); a Tucson, AZ, supermarket in 2011 (6 killed, 13 injured, including Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords); and a Charleston, SC, church in 2015 (9 killed).

The federal assault weapons ban (AWB) was in place from 1994 to 2004, prohibiting individuals from manufacturing, owning, or selling a semiautomatic assault weapon.[17] Under the ban, semiautomatic assault weapons, including rifles, were defined as having the ability to accept detachable magazines and two or more of the following features: (1) a folding or telescopic stock; (2) a pistol grip that protrudes conspicuously beneath the action of the weapon; (3) a bayonet mount; (4) a flash suppressor or threaded barrel designed to accommodate a flash suppressor; or (5) a grenade launcher. Additional criteria designating semiautomatic pistols and shotguns as assault weapons also were included in the ban.[18] The ban further listed 19 specific firearms, including the AR-15, that were banned from production, and included a prohibition on large-capacity ammunition-feeding devices (magazines) for civilian-owned guns capable of holding more than 10 rounds.[19]

During the ban, an assault-style rifle — most commonly an AK-47, expressly prohibited under the ban — was used in 16 percent of total mass shooting events. This was a reduction from the 10 years prior to the ban, when it was used in 21 percent of total mass shooting events — a one-fourth drop during the years of the federal gun ban.

However, Congress included a sunset clause that left the ban in effect only for 10 years from its enactment.[20] Though a number of attempts were made to overcome the sunset clause by either extending it or eliminating it completely, each such attempt failed and the ban expired as scheduled on September 13, 2004.[21] After the lapse, subsequent efforts were made almost every year to reinstate the ban or introduce new variations of the legislation, but each also failed to gain the necessary support in Congress.

During the ban, an assault-style rifle — most commonly an AK-47, expressly prohibited under the ban — was used in 16 percent of total mass shooting events. This was a reduction from the 10 years prior to the ban, when it was used in 21 percent of total mass shooting events — a one-fourth drop during the years of the federal gun ban. Although the ban did not stop[22] the use of assault-style rifles in mass shooting events, the relative frequency of their use declined during the years of the ban. Would a similar ban on semiautomatic pistols, the weapon of choice for a far greater number of mass shooters, result in a similar decrease? Further analysis is needed.

When considering prohibitions, like the federal assault weapons ban, policymakers should also consider other programs to reduce mass shootings. An ineffective background-check system, for example, was shown to be a problem in mass shooting cases both where assault-style rifles were and were not present.

When considering prohibitions, like the federal assault weapons ban, policymakers should also consider other programs to reduce mass shootings. An ineffective background-check system, for example, was shown to be a problem in mass shooting cases both where assault-style rifles were and were not present. When it was revealed that a reporting issue led to the Virginia Tech shooter, who had a well-documented history of mental illness that should have disqualified him from legally purchasing firearms, being able to walk into a gun store and pass the required checks, little remedial action was taken.[23] The very same issue allowed the Sutherland Springs shooter, who had a domestic violence conviction that was not reported in the background-check system, to acquire the guns used in his attack 10 years later.[24] Similarly, the Columbine shooting highlighted concerns over both gun show loopholes, whereby firearms sales can be conducted by private sellers without the purchaser submitting to a background check, and straw purchases,[25] while the numerous police referrals for the Parkland shooter and requests by family members to have his weapons removed from the home highlight situations used to support initiatives such as “red flag” laws.[26]

Whether it is background checks, gun show loopholes, mental health, or other glaring red flags, mass shootings are complex problems in need of equally multidimensional responses. Policymakers and researchers alike would do well to focus properly on the bigger picture supported by the data surrounding mass shootings and understand the multiple avenues that lead to these tragic events.

NOTES

[1] Christine Filer, “6 in 10 say ban assault weapons, up sharply in Parkland’s aftermath,” ABC News, April 20, 2018, https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/10-ban-assault-weapons-sharply-parklands-aftermath/story?id=54531298.

[2] According to the Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department’s final report, 869 people sustained injuries in the shooting. Aside from those struck by bullets or shrapnel, as counted above, 360 individuals were injured in other ways (e.g., from being trampled in the stampede of people trying to flee the concert grounds). For the remaining 96 people, the source of their injuries could not be confirmed. See LVMPD Criminal Investigative Report of the 1 October Mass Casualty Shooting, LVMPD Event Number 171001-3519 (Las Vegas: Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department, August 2, 2018), https://www.lvmpd.com/en-us/Documents/1-October-FIT-Criminal-Investigative-Report-FINAL_080318.pdf.

[3] It bears noting, however, that in this brief’s context, the Las Vegas shooting is an outlier for two reasons. First, 23 assault-style weapons were recovered from the perpetrator’s hotel rooms (see ibid), many of which had been fired during the course of the attack, whereas the shooters in Parkland and Sutherland Springs each used a single firearm. Second, more than half of the guns used by the Las Vegas shooter had been outfitted with bump stocks, which speed up the firing rate of the weapon to near that of fully automatic weapons; this was not used by either of the other two shooters. Undoubtedly, both of these played a role in the disparate casualty count of the shooting. See Lisa Marie Pane, “What’s happened with bump stocks since the Las Vegas attack?,” Associated Press, September 26, 2018, https://www.apnews.com/973119a6539b4c7d9387f3ef10aa3541.

[4] Maggie Astor and Karl Russell, “After Parkland, a New Surge in State Gun Control Laws,” New York Times, December 14, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/12/14/us/politics/gun-control-laws.html. The legislation that was passed focused on other areas, including (but not limited to) background checks, extreme risk protection orders (also known as “red flag” laws), safe storage, and waiting period laws. See also Allison Anderman, Gun Law Trendwatch: 2018 Year-End Review (San Francisco: Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence, December 14, 2018), https://lawcenter.giffords.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Giffords-Law-Center-Year-End-Trendwatch-2018_Digital-Spreads.pdf.

[5] Amanda Holpuch, “Six victories for the gun control movement since the Parkland massacre,” The Guardian, March 26, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2018/mar/26/gun-control-movement-march-for-our-lives-stoneman-douglas-parkland-builds-momentum.

[6] “Assault Weapons,” Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence, accessed January 2, 2019, https://lawcenter.giffords.org/gun-laws/policy-areas/hardware-ammunition/assault-weapons/.

[7] Typical conjecture suggests that AR-15s are the preferred weapon of mass shooters because it is incorrectly assumed that the “AR” stands for assault rifle. In reality, it stands for ArmaLite rifle, the company that originally developed the weapon. Moreover, though the popularity of assault-style rifles has grown among mass shooters, particularly in recent years, data still indicate that handguns are more commonly used.

[8] Jaclyn Schildkraut, Margaret K. Formica, and Jim Malatras, Can Mass Shootings Be Stopped? To Address the Problem, We Must Better Understand the Phenomenon (Albany: Rockefeller Institute of Government, Regional Gun Violence Research Consortium, May 22, 2018), https://rockinst.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/5-22-18-Mass-Shootings-Brief.pdf. Assault-style rifles in particular were present in 67 of the 340 shootings (20 percent).

[9] The presence of an assault-style rifle does not guarantee its use in the shooting, as some perpetrators showed preference for other weapons. Determining whether the assault rifle was used in a specific attack is difficult for most, as detailed reports on specific weapons usage from law enforcement are rare in shootings that are not of considerable societal interest, such as Las Vegas or Parkland, and the media often fail to report such details. Accordingly, in this brief, we specifically note only its presence, which should not be construed to mean that it was used within a given attack.

[10] David E. Petzal, “A Guide to the Types of Sporting Rifle Actions,” Field & Stream, July 22, 2011, https://www.fieldandstream.com/photos/gallery/guns/rifles/shooting-tips/2011/07/guide-rifle-actions-bolt-lever-pump-and-semi-auto.

[11] Gary Kleck, “Mass Shootings in Schools: The Worst Possible Case for Gun Control,” American Behavioral Scientist 52, 10 (2009): 1447-64.

[12] Jaclyn Schildkraut and H. Jaymi Elsass, Mass Shootings: Media, Myths, and Realities (Santa Barbara: Praeger, 2016).

[13] Schildkraut, Formica, and Malatras, Can Mass Shootings Be Stopped?

[14] This excludes the four years in which no mass shootings took place.

[15] Schildkraut, Formica, and Malatras, Can Mass Shootings Be Stopped?

[16] In two of the earliest shootings, it was unable to be determined whether or not an assault-style rifle was present. Accordingly, both cases were omitted from the analysis in this section.

[17] Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, H.R. 3355, 103d Cong., 2nd Sess. (1994). See also Vivian S. Chu, Federal Assault Weapons Ban: Legal Issues (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, February 14, 2013), https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R42957.pdf.

[18] See Former 18 U.S.C. §921(a)(30)(B).

[19] Jaclyn Schildkraut and Tiffany Cox Hernandez, “Laws That Bit The Bullet: A Review of Legislative Responses to School Shootings,” American Journal of Criminal Justice 39, 2 (2014): 358-74.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Jaclyn Schildkraut and Glenn W. Muschert, Columbine, 20 Years Later and Beyond: Lessons from Tragedy (Santa Barbara: Praeger, 2019).

[22] The AWB did not only encompass assault-style rifles — semiautomatic handguns and shotguns also were prohibited if they met certain criteria. Among the semiautomatic handguns that were banned was the Intratec Tec-DC9. The Tec-9, as it is sometimes referred to, originated in Sweden but quickly became one of the most widely used guns in American crime. The Tec-DC9 became even more prominent in the context of mass shootings after it was used by one of the perpetrators in the April 20, 1999, shooting at Columbine High School, an event that took place nearly halfway through the 10-year period when the federal AWB was in effect.

[23] Schildkraut and Hernandez, “Laws That Bit The Bullet.”

[24] Charley Locke, “How the Sutherland Springs Shooter Got a Gun Despite a Domestic Violence Conviction,” Texas Monthly, November 6, 2017, https://www.texasmonthly.com/the-daily-post/sutherland-springs-shooter-got-gun-despite-domestic-violence-conviction/.

[25] See Schildkraut and Muschert, Columbine, 20 Years Later and Beyond. Straw purchases refer to those that are made on behalf of another person. Prior to the Columbine shooting, a friend of the two perpetrators, Robyn Anderson, acquired three of the weapons used in the attack at a local gun show. Since Anderson did not want to submit to a background check for the purchases, the perpetrators specifically sought out private dealers who were not required to perform such inquiries as permitted by a gap in the Brady Law. This “gun show loophole” became the focus of considerable legislative attention, particularly at the federal level, after the shooting but has failed to be remedied. See also Schildkraut and Hernandez, “Laws That Bit The Bullet.”

[26] Initial Report Submitted to the Governor, Speaker of the House of Representatives and Senate President (Parkland: Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School Public Safety Commission, January 2, 2019), http://www.fdle.state.fl.us/MSDHS/CommissionReport.pdf. According to the report, there were 69 separate documented incidents where the Parkland shooter threatened others, talked about firearms or other weapons, or engaged in violence or other concerning behaviors. Prior to the shooting, there also had been 43 different contacts with the Broward County Sheriff’s Office and the perpetrator’s family. Of these, half involved the perpetrator either alone or with his brother, who was the sole focus of the remaining contacts.

Jaclyn Schildkraut is an associate professor of criminal justice at SUNY Oswego, a member of the Regional Gun Violence Research Consortium, and a national expert on mass shootings.