As the coronavirus outbreak continues to wreak havoc and the start of the new school year approaches, public school districts across the country are implementing plans designed to safely deliver quality instruction to their students. Some families sense that in this time of turmoil and uncertainty, however, private schools may be more flexible to meet new safety guidelines and are better equipped to provide either—or both—virtual or in-person instruction. This alternative, of course, is available only to families who can afford it.

Other costly schooling options are evolving as parents respond to what they view as disruptive public school re-opening plans. Pooling funds with neighbors to hire an in-person instructor for selected children, known as forming “pods,” hiring private tutors to homeschool children for hours each day, and other creative alternatives to district schools’ transformed approaches to instruction are popping up all across the nation. And virtually all of them are out of reach for many low-income families.

As such, concerns are being raised that this unusual school year may significantly widen achievement gaps between those who are privileged and those who are not. A working paper out of the Annenberg Institute at Brown University notes that as a result of the Spring 2020 school shutdowns students will begin school this fall retaining only about two-thirds of a normal year’s learning in reading and about half of a typical year’s learning in math. The projections for students from low-income schools are significantly worse than for high-income schools, revealing a widening of the achievement gap even at the start of this school year. NBC News quotes one of the co-authors of the study, professor Jim Soland of the University of Virginia School of Education: “Now, if you imagine parents in high end schools are also going out and getting additional resources paying for a tutor and the like, it’s hard to imagine that not further exacerbating achievement gaps.” Another report about wealthy parents creating education alternatives for their own children states bluntly, “Those who can’t afford to do so risk their kids’ ability to stay on track.”

Part of the solution to this inequity may be to help increase access to private schools for low-income families, and the US Supreme Court recently cleared the way, legally speaking, for tax credit-based tuition scholarship programs to grow as an educational option for these families.

Eighteen states have enacted programs that offer tax credits to individuals and corporations for donations to nonprofit organizations that in turn provide tuition scholarships. Tax credits reduce the tax liability compared with deductions which reduce taxable income. As a result, these credits provide a more generous tax benefit than the typical deductions that allowed for contributions to certain nonprofit organizations, thus stimulating greater levels of private donations for education. Nearly all of these state programs—15 of the 18—require these scholarships to be made available only to income-qualifying families, tying eligibility for a scholarship to a multiple of the federal poverty line or the reduced-priced school meal program’s income standards. Approximately 300,000 low-income students across these 18 states are currently participating in these scholarship programs.

The financial stress states are experiencing in the wake of the COVID pandemic is having an effect on existing programs, as private donations to scholarship-giving organizations wane, and is likely to make states hesitant about establishing new programs even as demand grows. Several states with existing tax credit scholarship programs are using their allocations under the $3 billion Governor’s Emergency Education Relief Fund (GEER) component of the federal CARES Act funding plan enacted in June to increase or ensure that these options are and remain available to low-income families. Florida is setting aside $30 million as a safety net for its tax credit scholarship program in case contributions from corporations, which fund that state’s program, decline. And New Hampshire allocated $1.5 million in new relief funds directly to the scholarship-granting organizations operating the state’s income-tested tax credit-funded program (the proportion of these scholarships going to students of color is about 50 percent higher than the state’s proportion of students of color generally). Other states are using GEER funds to directly support low-income families making private-school choices. For example, Oklahoma allocated $10 million in temporary aid to help an estimated 1,500 low-income families who, because of a loss of income due to COVID-19 conditions, cannot afford to continue to send their children to private school; and, South Carolina set aside $35 million in GEER funds for this school year to help families within 300 percent of the federal poverty line stay in or transfer to a private school, a program that projects to help 5,000 students.

Tax-incentivized private school scholarships are not without their critics, however, and in January 2020 the US Supreme Court heard oral arguments in a case challenging Montana’s education tax credit scholarship program.

Constitutional Issues: Funding Religious Schools, “Baby Blaine Amendments,” and the US Supreme Court’s Espinoza Ruling

Opponents of these programs traditionally contend that if parents use a scholarship that is incentivized with public tax benefits to help pay for their child’s tuition at a private school that is affiliated with a particular religion, it becomes a form of public subsidy of religious education that is banned under most state constitutions. Supporters traditionally maintain, among other things, that these public subsidies accrue directly to individuals and as individuals they make independent choices about where to use the scholarships, breaking any constitutional link to support of religious schools.

Earlier this year, the Supreme Court of the United States settled the issue. On June 30, 2020, the Court ruled in Espinoza, et al v. Montana Department of Revenue, et al that these tax-credit scholarship programs do not conflict with such state restrictions, validating existing state scholarship programs and clearing a path for new ones.

Origin of State Constitutional Prohibitions

In his attempt to win the White House, and riding a national wave of intense anti-Catholic bigotry, in the 1870s US Senator James G. Blaine of Maine called for a federal constitutional amendment that would prohibit public funds from flowing to any institution under the control of a religious organization. The primary target of this action were the country’s schools. Although most public schools at the time were solidly Protestant in their underlying establishment and instruction (including daily prayer, hymn singing, and teaching from the King James Bible), the notion of church-controlled schools only applied at the time to Catholic (and eventually Jewish) schools.

Sparked by the potato famine in the 1840s, America had experienced a large and rapid uptick in immigration by Irish Catholics and, objecting to the form of religion being espoused in existing public schools, these new Americans began establishing their own schools designed to welcome children of the Catholic faith. An entire new national political party, the Know Nothings, developed in large part to oppose this influx of Catholics, too, and Blaine’s “anti-aid” movement sprung forth from that.

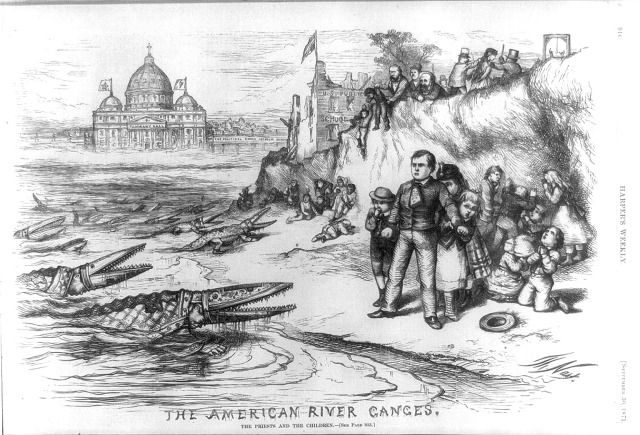

A famous anti-Catholic school sketch by renowned political cartoonist Thomas Nast that ran in American newspapers in 1871 (and again in 1875) showing crocodile-like Catholic clerics coming to snap up Protestant schoolchildren. (Also reproduced and included in Justice Alito’s concurring opinion in Espinoza v. Montana).

While not successful at securing either the presidency or a federal constitutional amendment, Blaine’s ability to focus the country’s anti-Catholic sentiment on the issue of school funding eventually resulted in more than three dozen states enacting “baby Blaine amendments” to their own state constitutions. This included New York State, which adopted its “baby Blaine” anti-aid provision in 1894. Congress even made the adoption these anti-aid amendments a requirement when considering whether to admit a territory to the Union as a new state (Espinoza v. Montana, p. 37, 591 U. S. ____ (2020)).

Espinoza v. Montana

More recently, on January 22, 2020, the US Supreme Court heard oral arguments in Espinoza v. Montana. Kendra Espinoza is a single mother who holds multiple jobs, trying to earn enough to send her daughters to a local private school. She was eligible for the state’s tuition scholarship program, but Montana officials told her and the other two plaintiff parents that she couldn’t use the scholarship at her choice of school because it was a Christian school. Montana cited its constitutional provision banning aid to institutions under secular control.

In the majority opinion, Chief Justice John Roberts wrote, “When otherwise eligible recipients are disqualified from a public benefit ‘solely because of their religious character,’ we must apply strict scrutiny,” and he concluded succinctly: “A State need not subsidize private education. But once a State decides to do so, it cannot disqualify some private schools solely because they are religious” (Espinoza v. Montana, p. 17; p. 20, 591 U. S. ____ (2020)). This decision built most recently on the precedence of Trinity Lutheran v. Comer, a case where the US Supreme Court overturned Missouri’s decision to deny a church access to a state playground renovation program simply because it was a religious institution.

Common Features of State Tax Credit Scholarship Plans

With constitutional questions now settled, states with tax credit scholarship plans can proceed unfettered. And states considering establishing these programs, as New York did recently, can look to existing programs for design ideas and best practices.

Fundamental Features of State Tax Credit Scholarship Programs

| State | Year Enacted | Type of Donor Eligible for Tax Credit | % of Donation Eligible for Credit | Annual Limit on Tax Credit Per Donor | Total Annual Program Amount | Initial Eligibility Requirements | Scholarship Limit | Annual # Scholarship Participants | Annual Scholarship Funds Expended |

| Alabama | 2013 | Individual | 100% | 50% of tax liability (single or couples) up to $50,000 | $30M | Must qualify for federal free and reduced-price meal program; Priority to students attending failing schools | Lesser of tuition+fees or: K-5: $6,000 6-8: $8,000 9-12: $10,000 | 4,006 (2019-20) | $23.9M (2019-20) |

| Corporate | 100% | 100% of tax liability | |||||||

| Arizona | 1997 | Individual | 100% | $569 single; $1,138 couples | None | None | 100% of tuition | 32,585 (2016-17) | $58.0M (2016-17) |

| 2006 | Corporate | 100% | None | $102.5M | ≤185% reduced-price meal eligibility level; plus other restrictions | K-8: $5,600 9-12: $6,900 (2020-21) | 20,964 (2016-17) | $51.8M (2016-17) | |

| 2009 | Individual (Lexie's Law) | 100% | None | $5M | Must have an IEP or 504 Plan | Lesser of tuition or 90% state per pupil aid | 1,103 (2016-17) | $51.8M (2016-17) | |

| 2012 | Individual (PLUS) | 100% | $566 single; $1,131 couples, only if contributed fully to original individual scholarship plan | None | Student must attend public school immediately preceeding | None | 22,348 (2016-17) | $33.0M (2016-17) | |

| Florida | 2001 | Corporate | 100% | None | $698.8M | Household income ≤260% federal poverty level; priority to free and reduced-price meals eligibles | Lesser of tuition or: K-5: 88% of state per pupil funding 6-8: 92% 9-12: 96% Scholarships decrease as income increases | 108,570 (2019-20) | $672.6M (2019-20) |

| 2018 | Individual | Up to $105 of sales tax charged for a new vehicle purchase | None | Victims of bullying at a district public school | 271 (2019-20) | $1.8M (2019-20) | |||

| Georgia | 2008 | Individual | 100% | Single: $1,000 Couples: $2,500 | $100M | Must attend public school | Avg. state+local expenditure per pupil | 13,895 (2018-19) | $55.7M (2017-18) |

| Corporate | 100% | LLC/S/Partnership: up to $10,000; Corps: 75% of liability | |||||||

| Illinois | 2017 | Individual | 75% | $1M | $75M | Household income ≤300% federal poverty level, with priority for ≤185% and for students in lowest-performing schools | Lesser of tuition or 100% of avg. state operational expense per pupil; scholarships decrease as income increases | 7,718 (2018-19) | $57.0M (2017-18) |

| Corporate | 75% | $1M | |||||||

| Indiana | 2009 | Individual | 50% | None | $15M | Household income ≤ 200% reduced-price meal eligibility level | Tuition+fees | 10,146 (2018-19) | $21.8M (2018-19) |

| Corporate | 50% | None | |||||||

| Iowa | 2006 | Individual | 65% | None | $13M | Household income ≤ 400% federal poverty level | Tuition | 10,791 (2018-19) | $17.4M (2018-19) |

| Corporate | 65% | Limited to 25% of program | |||||||

| Kansas | 2014 | Individual | 70% | $500,000 | $10M | Household income ≤ 100% reduced-price meal eligibility; Enrolled in one of the 100 lowest-performing elementary schools | Lesser of tuition+fees or $8,000 | 504 (2019-20) | $2.3M (2019-20) |

| Corporate | 70% | $500,000 | |||||||

| Louisiana | 2012 | Individual | 100% | None | None | Household income ≤ 250% federal poverty level; Attended public school immediately prior | K-8: avg. state Minimum Foundation Program per pupil funding 9-12 : 90% | 2,115 (2018-19) | $9.3M (2018-19) |

| Corporate | 100% | None | |||||||

| Montana | 2015 | Individual | 100% | $150 | $3M | None | 50% of avg. per pupil expenditure | 25 (2016-17) | 12,500 (2016-17) |

| Corporate | 100% | ||||||||

| Nevada | 2015 | Corporate | 100% | None | $26M / $6M | Household income ≤ 300% federal poverty level | $8,262 | 1,491 (2019-20) | $9.4M (2019-20) |

| New Hampshire | 2012 | Individual | 85% | $1M, and only if subject to interest and dividends tax | $5.1M | Household income ≤ 300% federal poverty level; Set proportion of scholarships for students from public schools; 40% must go to those eligible for free and reduced-price meals | $2,762 avg.; $4,749 min for SpEd | 413 (2018-19) | $895,000 (2018-19) |

| Corporate | 85% | $1M | |||||||

| Oklahoma | 2011 | Individual | 50% for one year or 75% for two consectuive years | Single: $1000 Couples: $2000 | $3.5M for scholarships; $1.5M for education improvement grants to schools. | Household income ≤ 300% reduced-price meal eligibility | Greater of $5,000 or 80% of local district avg. per pupil spending; $25,000 - SpEd | 2,555 (2018-19) | $5.2M (2018-19) |

| Corporate | 50% for one year or 75% for two consecutive years | $100,000 | |||||||

| Pennsylvania | 2001 | Corporate - Educ.Improvement | 75% for one year or 90% for two consecutive years | $750,000 | $185M | Household income ≤ $90,000 plus $15,842 per dependent; higher income allowed for special ed | Tuition & fees | 37,725 (2017-18) | $68.5M (2017-18) |

| Corporate - Opportunity | 75% for one year or 90% for two consecutive years | $750,000 | $55M | Household income ≤ $90,000 plus $15,842 per dependent; higher income allowed for special ed; must live in a low-achieving school zone | Lesser of tuition & fees or $8,500; $9,000 for students at economically disadvantaged schools; $15,000 - SpEd | 14,419 (2017-18) | $35.9M (2017-18) | ||

| Rhode Island | 2006 | Corporate | 75% for one year or 90% for two consecutive years | $100,000 | $1.5M | Household income ≤ 250% federal poverty level | None | 515 (2019-20) | $1.3M (2019-20) |

| South Carolina | 2013 | Individual | 100% | 60% of tax liability | $12.0M | Students w/ disabilities | Lesser of tuition+fees or $11,000 | 2,327 (2017-18) | $11.6M (2017-18) |

| Corporate | 100% | 60% of tax liability | |||||||

| South Dakota | 2016 | Insurance Co.'s | 100% | None | $2M | Household income ≤ 150% reduced-price meal eligibility | Tuition+fees, and must avg. no more than 82.5% of the state per pupil allocation | 775 (2019-20) | $1.3M (2019-20) |

| Virginia | 2012 | Individual | 65% | $125,000 | $25M | Household income ≤ 300% federal poverty level; ≤ 400% - special ed students; attended public school immediatley preceeding | Lesser of tuition+fees or 100% of avg. state per pupil funding; 300% - SpEd | 4,505 (2018-19) | $14.3M (2018-19) |

| Corporate | 65% | None |

Among the more common and innovative approaches states have taken in their tax credit scholarship programs are to incorporate the following features:

- Income eligibility requirements: Nine state programs tie income limits on eligibility for a scholarship to the federal poverty rate (AL; FL; IL; IA; LA; NV; NH; RI; VA); another five tie eligibility to the federal free and reduced-price school meals program (AZ; IN; KS; OK; SD). Pennsylvania sets a specific dollar amount for family income as an eligibility limit. Illinois requires first preference in awarding scholarships to go to families with even lower incomes (185% of the federal poverty rate) than its overall income-eligibility criterion (300% of the federal poverty rate).

- “Switcher” provisions: To avoid subsidizing families who already send their children to private schools, some state programs require that new scholarships go only to qualifying students who are currently enrolled in public schools (AZ; GA; KS; LA; NH; SD; VA). Programs without such “residency” or “switcher” requirements, but with income-eligibility tests, provide equal assistance based solely on a family’s economic ability to pay for their choice.

- Continuing eligibility. Once a student qualifies and receives an initial scholarship, Louisiana’s and Oklahoma’s programs maintain a student’s eligibility each year as long as they choose to use the scholarship regardless of any change in their families’ economic status; South Dakota grants a 3-year initial eligibility term. Some states – including Alabama and Florida – relax initial income-eligibility limits for current scholarship recipients seeking to renew for a subsequent year.

- Scholarship amount: State programs typically cap the value of the scholarship at a school’s regular tuition charge or tuition plus fees (AZ; IN; IA), at the lesser of tuition or a prescribed dollar amount (AL; AZ; KS; NV; NH; PA; SC), or at the state’s average per pupil expenditure or a percentage of that amount (AZ; FL; GA; IL; LA; OK; SD; VA). A few state programs allow higher scholarship amounts for students with special needs (NH; PA; VA).

- Students in low-performing schools: Alabama requires scholarships to be given with a priority for students attending failing schools, Kansas’s program allows only students attending one of the state’s lowest-performing 100 schools to be eligible for a scholarship, and one of Pennsylvania’s programs allows higher scholarship amounts for students currently attending economically disadvantaged schools.

- Credit limits: In some states the percentage of charitable donation allowed to count as a credit is as low as 50 percent (IN) or 65 percent (IA; VA) of the value of the donation; half of all state programs allow 100 percent of a donation to count toward a tax credits (though often subject to a dollar-cap limit).

- Stimulating donor support for public schools: Oklahoma included in its program tax credits for donations to nonprofit organizations that give grants to public schools and districts for education improvement activities, a much more generous benefit than a typical tax deduction.

New York’s Efforts on Education Tax Credit Programs

New York Governor Andrew Cuomo called for the creation of a tax credit education scholarship program most recently in 2015, proposing the “Parental Choice in Education Act,” and the next year included an education scholarship plan in his official 2016-17 Executive Budget proposal (Part S of S.6409-A/ A.9009-A). With bipartisan support echoing the Governor’s action, the New York State Senate passed its version of an education tax credit scholarship program in 2016. While the state Assembly never acted on its proposal, at its high-water mark the program bill had 108 sponsors, 76 of whom were Democrats and 32 of whom were Republicans.

Governor Cuomo’s Plan

The primary component of Governor Cuomo’s plan established $50 million in available tax credits for donations to nonprofit scholarship-granting institutions. With the credit capped at 75 percent of the value of donations, the available tax credits allowed would generate up to $67 million in scholarships for children from low- and middle-income families. These scholarships could be used for tuition at private schools or to pay tuition charges for a transfer to an out-of-district public school. The plan also similarly allocated another $20 million in available tax credits to stimulate $27 million in new private donations to organizations that gave grants or other education improvement support to local public schools and districts.

Other components of the plan included:

- Families with incomes of $60,000 or less could claim an annual tax credit of up to $500 against private school tuition charges. This program component, estimated to cost $70 million, was projected to benefit the families of approximately 140,000 students across the state, approximately 35 percent of current private K-12 enrollment statewide.

- Teachers would be entitled to a tax credit of up to $200 per year to cover the cost of any school supplies purchased as part of their job. This component was projected to total $10 million in tax credits.

In total, the plan authorized $150 million in new tax credits for education.

New York State Senate Plan

The State Senate’s 2016 version of an education tax credit plan (S.1976-A [2016]) allowed 90 percent credit for donations to public schools and districts, to school improvement organization or funds that support local schools, and to qualifying tuition scholarship-granting organizations. The proposed program was capped at $150 million initially, but scaled up to $300 million over the subsequent two years. The bill also included the $200 refundable tax credit for teachers if they purchase school supplies for their classrooms that was included in Governor Cuomo’s plan.

The Senate passed its education tax credit program bill in January 2016 with a bipartisan vote of 47 to 15. Similar legislation was introduced for the 2019-20 legislative session (S. 8005); there was no companion bill introduced in the State Assembly, however.

New York State Assembly Plan

The State Assembly proposed similar legislation that same year (A.2551-A [2016]). This version of the education tax credit program matched the Governor’s percentage of donations that could be taken as a credit, 75 percent, and grew the program over three years to reach a maximum of $300 million in tax credits to generate $400 million education support donations. This proposal would allow half of the credits to be for donations made to scholarship-granting organizations and half for donations to local school support organizations. A $50 million program for refundable tax credits for teacher-purchased supplies also was included.

The Assembly’s education tax credit plan was never brought to a vote.

Conclusion

In their search for the best school setting for their children this coming school year amid the ongoing disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, many parents are opting for private schools, independently hired tutors, “pandemic pods,” or other creative alternatives. Many of these options, however, are available only to families wealthy enough to afford them. Concerns are growing that this new trend will only exacerbate the learning gap students from low-income families face.

With the US Supreme Court’s ruling in Espinoza v Montana superseding the constitutional concerns some groups raised about education tax credit scholarship plans, including those for New York (see, for example, the NYCLU’s opposition), continuing, expanding, and growing new programs will open access to private schools for tens of thousands of low-income schoolchildren looking for such alternatives in the time of COVID-19.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Brian Backstrom is director of education policy studies at the Rockefeller Institute of Government.