Earlier this summer the Supreme Court overturned a 1984 case known as Chevron v. The Natural Resources Defense Council in a case called Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo. Prior to this overturning, Chevron had been central to allowing executive branch administrative agencies to make reasonable interpretations of law (often referred to as the Chevron doctrine). Under this doctrine administrative agencies issued rules and regulations, based on their reasonable interpretation of ambiguous laws, on everything from environmental standards impacting food safety to drug safety in healthcare. The Supreme Court’s decision clearly shifts power from executive branch agencies to the legislative branch and the courts when laws are ambiguous. Since many laws lack detail, are broad in scope, or delegate agencies authority to promulgate rules (though rules under explicitly delegated authority may be less scrutinized), the federal government regularly issues rules and regulations that help fill in ambiguities and make the laws implementable. The impacts of the overturning of the Chevron decision on healthcare could be far-reaching. It is anticipated that in healthcare this could mean slower and diminished executive agency capacity on issues such as price transparency, accelerated drug approval, or interoperability standards for the exchange of health data.

One way that the executive branch of government retains significant power over healthcare is through the use of Medicaid waivers. Medicaid, an important publicly funded program that provides health insurance coverage to over 75 million Americans who generally qualify because of their income level or disability, is jointly funded by the federal and state governments and primarily administered at the state level. The federal government sets minimum requirements as to what populations and what services must be covered but also grants states some discretion over the amount, duration, and scope of the program. States have even more discretion over the program when they use Medicaid waivers. These waivers allow states to “waive” certain requirements under the founding statute (The Social Security Act of 1965). A common waiver states use is the 1915c, which allows states to provide services to additional and specific populations not automatically eligible for Medicaid because of their income or disability (e.g., community-based services to people with developmental disabilities, HIV, or traumatic brain injuries, for example).

States and the federal government have used this authority in healthcare for decades to shape the Medicaid program. There are now 64 approved 1115 waivers across 47 states.

In the last two decades, states have also increasingly used the authority granted to them under Section 1115 of the Social Security Act to enact broad-ranging changes to their state’s Medicaid programs. These waivers have allowed states to do everything from instituting work requirements or requiring premium payments of enrollees to expanding the populations or services covered, such as to people at higher income levels than current federal thresholds dictate.

Section 1115 waivers give states broad authority to test new and innovative ways of administering the Medicaid program. This has sometimes been referred to as executive federalism, which is broadly defined as, “the processes of intergovernmental negotiation that are dominated by the executives of the different governments within the federal system.” States and the federal government have used this authority in healthcare for decades to shape the Medicaid program. There are now 64 approved 1115 waivers across 47 states.

In January 2024, the federal government approved an additional amendment to New York State’s 1115 waiver. The waiver, known as the New York Health Equity Reform (NYHER) waiver is intended to address, “social determinants of health (SDOH)” to improve health equity among the state’s Medicaid-enrolled population. Social determinants of health are broadly defined as the conditions in which people are born, live, work, and play that can impact their health and healthcare.

To better address social determinants of health, New York State was given permission by the federal government to cover a new array of services for specific populations not otherwise covered by Medicaid, including pregnant persons and persons up to 12 months postpartum, individuals with serious mental illness, individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities, and others. The new Health-Related Social Needs (HRSN) services that these populations will have access to under Medicaid can include housing, transportation, nutrition, case management, and navigation of health and related services. Examples of the services under these broad categories include medically tailored meals, housing navigation, rent subsidies, and home modifications. These services had not been previously covered under the state’s Medicaid program, although the federal government in 2021 encouraged states to cover HRSNs. In that correspondence, the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), which oversees Medicaid, defined HRSNs as “an individual’s unmet, adverse social conditions that contribute to poor health outcomes.” Following the 2021 guidance, in 2023, CMS released guidance to more clearly define a framework for states’ use of HRSNs.

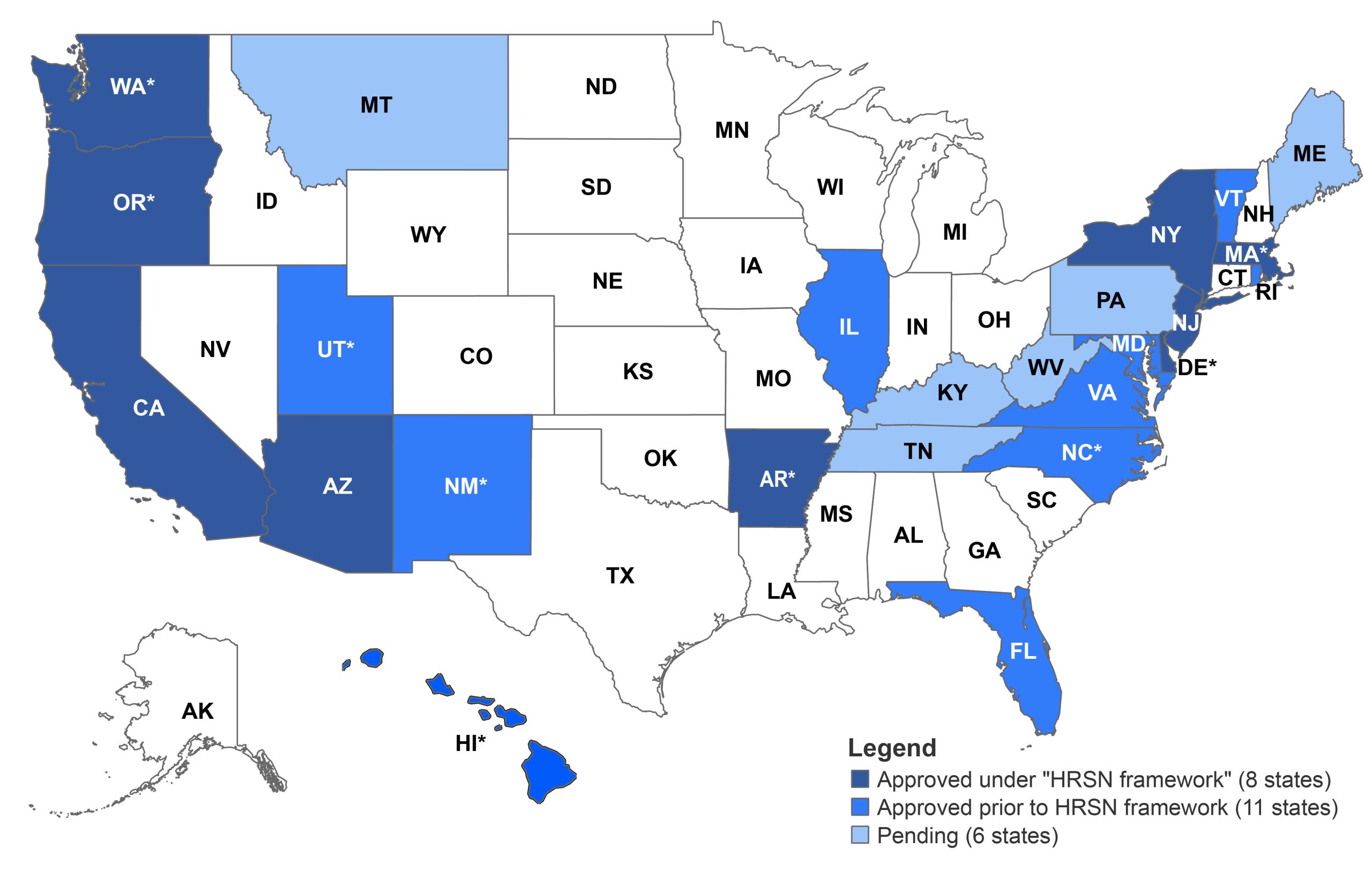

As noted in a chart created by the Kaiser Family Foundation, 11 states had approved waivers with HRSN-type services prior to the 2023 framework, while at least eight states now have approved waivers with the HRSN framework, and at least a half dozen other states have pending approvals. Other states, in addition to New York, with approved waivers that include the HRSN framework include Washington, Oregon, California, Arizona, Massachusetts, and New Jersey. Some of the states that had already begun to focus on HRSN even prior to the 2023 framework include Florida, North Carolina, Virginia, Illinois, and Vermont, and there are now a handful of states with pending approvals.

Section 1115 Waivers with Provisions Related to Social Determinants of Health (SDOH), as of February 2024

* Some states with approved 1115 waivers also have additional SDOH provisions pending at CMS.

SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation.

Some states have focused on eligibility expansions or benefit expansions in behavioral health. Like New York, Oregon’s waiver includes housing and nutrition supports. But unlike New York, Oregon’s approved list of covered HRSN’s also includes “climate supports.” Examples include devices that maintain a healthy air temperature or mini fridges that can keep medications cold during a power outage. At the same time, New York is covering a wider array of housing services when compared to Oregon. Perhaps, in the future, states will copy from one another and add populations and services that they see other states focused on. States can do this by choosing to request amendments from the federal government for their waivers.

It will be interesting to see how New York’s and other states’ waivers take shape. It will be even more interesting to learn whether these states’ recent efforts to improve health equity are working. As of now, additional data are needed to determine the impact of these efforts. At the same time, it will be important to observe how states continue to use waivers as a means to drive policy. Political ideologies of all types have used waivers to help drive policy change. Since states have to get permission from the federal government for these changes, it is the federal government that tends to drive which direction states will go with their waiver policies. Regardless of the Supreme Court’s decision in Loper Bright, waivers provide an important policymaking mechanism to drive change. And even if federal and state executives lose authority to shape certain aspects of healthcare delivery in some ways, 1115 waivers have been and may continue to be a useful tool for innovation and reform for healthcare especially for the millions of Americans that rely on Medicaid for insurance coverage.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Courtney Burke is senior fellow for health policy at the Rockefeller Institute of Government.