Why Medicaid Matters

New York’s Medicaid program provides health insurance to nearly seven million New Yorkers, or more than one-third of the state’s entire population, and it is a critically important way for people to get healthcare. Jointly funded by federal and state revenue, the program is primarily administered by the state. Not only do millions of people rely on Medicaid for life-saving healthcare coverage, but its value as measured by how much is spent each year would rank New York’s Medicaid program higher than well-known mega-companies like Target and Tesla on the Fortune 500 list. When considered as an economic industry, New York’s Medicaid program helps keep thousands of businesses running and hundreds of thousands of people employed. And, most importantly, it cares for those more vulnerable in society, including older adults, those with disabilities, and the lowest-income New Yorkers. Recently, the United Hospital Fund teamed up with the Rockefeller Institute to host two discussion forums with experts in Medicaid administration to discuss current challenges and opportunities for improvement. Drawing from the experiences and themes highlighted in those forums in combination with research conducted by the Rockefeller Institute on other states’ Medicaid program structures, below we highlight a number of potential areas for improving Medicaid administration.

Why Medicaid Administration Matters

Given the scope and impact of Medicaid—more than $100 billion in annual expenditures for a healthcare program that serves seven million New Yorkers—it is imperative that the administrative apparatus entrusted with running it has the structure, authority, and capacity to deliver the best services and outcomes for beneficiaries in an efficient and cost-effective way. Program managers who are focused on collecting data on the program, analyzing this data, and setting goals for improvement, as well as broader leadership that creates policies and programs that drive this improvement, are essential components of good Medicaid administration. Properly structured administration also includes the ability to set payment rates effectively for services, speedily contract for massive amounts of all types of healthcare delivery services, and pay bills in a timely manner.

Because the program is constantly changing and adapting to different policies and needs, agility and innovation are also important. Quick, clear, and effective communication is required for those using the program, as is the ability to share important data and information with beneficiaries and providers about spending, policy changes, or outcomes. Complying with constantly changing rules about who is eligible, what services they are eligible for, and the rules for obtaining or paying for those services requires a sophisticated legal team devoted solely to Medicaid administration. Following a thorough assessment of the administrative structure of New York’s Medicaid program, including comparative research into the policies and practices of other states as well as public comment and discussion at two forums, we have identified shortfalls in the current structure of the program. This administrative structure does not appear to allow the Office of Health Insurance Programs to hire adequate staff into appropriate positions in a timely manner with salaries commensurate with the requirements and responsibilities of these positions. The administration also lacks the ability to procure necessary services or innovate programs at the speed necessary to serve its customers.

In New York, Medicaid is administered by the Office of Health Insurance Programs (OHIP), one of more than half a dozen administrative subdivisions within the New York State Department of Health (DOH). As such, some important functions are not at full capacity:

- OHIP staff have noted that the office currently faces a staff vacancy rate of more than 50 percent, with fewer than 1,000 employees performing work envisioned for twice that number. And while total Medicaid expenditures managed by OHIP have grown by more than 38 percent over the past five years, the number of staff at OHIP increased by less than 10 percent.1

- Federal compliance and accountability reporting is managed by offices in the Department of Health other than OHIP. This separation of administrative responsibilities and accountability could result in both inefficiencies and unintended delays or lapses.

- DOH is the designated single agency for CMS, meaning that OHIP, which regularly collects program and participation data, cannot have a direct data-sharing relationship with CMS. Although OHIP communicates regularly and directly with CMS on policy matters, as of the writing of this paper, OHIP must defer to DOH to do federal financial reporting and administrative claiming.

These challenges expose opportunities that could be explored to improve and enhance the administration of Medicaid in New York.

The Challenges for Improving Medicaid Administration

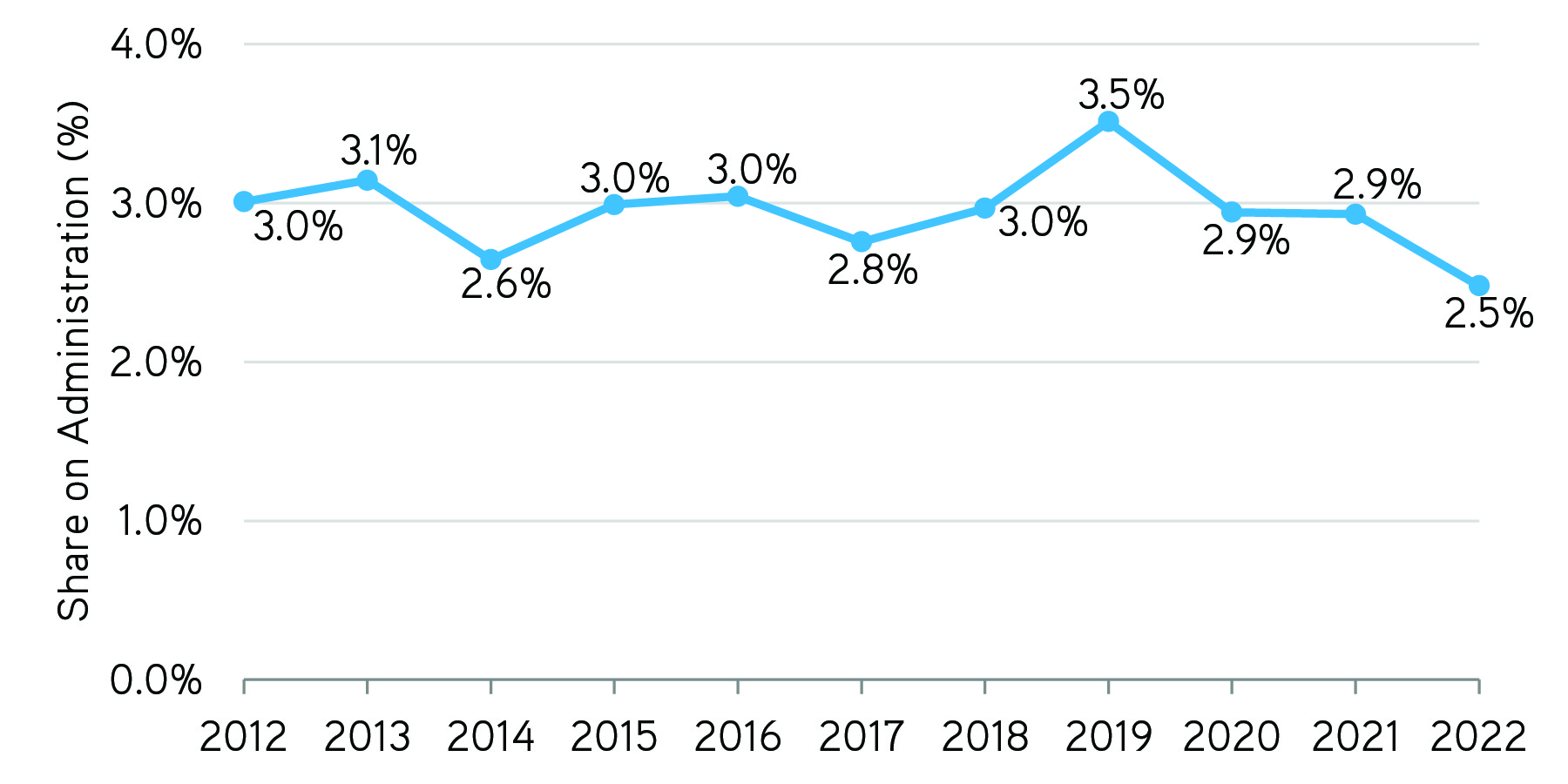

New York ranks in the top quartile of all states nationally in per capita spending on Medicaid ($11,203 in 2025). It also ranks near the top in terms of the healthcare services and benefits it provides. Despite the higher level of services provided by New York, it ranks near the bottom (47th) in terms of administrative spending as a percentage of program expenditure. In other words, New York is providing more services than other states but spending less on administering those services. To a certain extent, low administrative spending is a positive program attribute and an indication that the program is efficiently run. However, if administrative spending is too low relative to services, it can be a sign of insufficient resources being dedicated to vital program aspects, such as efficient contracting processes or speedy legal reviews, that actually result in negative program outcomes. Because low administrative spending could indicate either administrative efficiency, lower than necessary administrative capacity, or a combination of the two, it is worth determining if the program could be administered differently in ways that would attract and retain a robust workforce, more effectively procure services, pay providers and vendors quickly, and better ensure that program services are of the type, quality, and availability to clients that is needed and expected. It is also worth considering if there are more ways to strengthen data systems that can provide timely information to administrators, stakeholders, and the public to keep the program accountable and improve outcomes for enrollees.

Learnings from the forums held by the Rockefeller Institute of Government and the United Hospital Fund indicate that there are opportunities to improve the administration of Medicaid in New York and obtain better results.

Percent of Medicaid Spending on Administration in New York

SOURCE: Data on programmatic and administrative spending based on total net expenditures obtained from Expenditure Reports from MBES/CBESCMS. Form available at “Expenditure Reports From MBES/CBES,” Medicaid.gov, accessed July 15, 2025.

Examples of Where Administration Might Be Improved

The Rockefeller Institute’s comparative research on Medicaid administration across a handful of states shows that there are areas where administration could be improved.

| State | Governance and Administrative Structure | Reporting Hierarchy |

| New York | Medicaid program administered by an office within an “umbrella” Agency: the Office of Health Insurance Policy (OHIP) operates within the Department of Health (DOH). | The commissioner of DOH has oversight of OHIP, and the director of OHIP reports to the commissioner. Both positions are appointed by the governor; the appointment of the DOH commissioner requires confirmation by the state Senate. |

| Comparison States | ||

| Arizona | Medicaid program is administered by a stand-alone agency, the Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System (AHCCCS). | The director of AHCCCS is appointed by the governor and reports to the governor’s office. |

| California | California Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) administers the state’s Medicaid program. While DHCS, along with other state departments, is located as part of California’s Health and Human Services (HHS) Agency, DHCS is mission-specific. | The director of DHCS is appointed by the governor and reports to the secretary of HHS. |

| Massachusetts | MassHealth is administered by an office within an “umbrella” agency, the Executive Office of Health and Human Services (EOHHS). | The director of MassHealth reports to the secretary of EOHHS; both are appointed by the governor. An independent state health agency, the Health Policy Commission (HPC), also monitors healthcare spending in the state. |

| Oregon | The Oregon Health Plan (OHP) is administered by the Oregon Health Authority (OHA), a stand-alone agency that administers Medicaid and a variety of other public health programs. | The director of OHP reports to the director of OHA; both are appointed by the governor. Oversight of Medicaid and OHA is provided by the nine-member Oregon Health Policy Board (OHPB). |

| Pennsylvania | Medicaid is administered by an office within the “umbrella” state Department of Human Services (DHS). | The Medicaid director reports to the director of the DHS; both positions are appointed by the governor. |

| Vermont | Medicaid is administered by the Department of Vermont Health Access (DVHA), an office within the state Agency of Human Services (AHS). | The commissioner of DVHA reports to the director of AHS; both positions are appointed by the governor. |

| Washington | Apple Health was transferred out of a state agency and is now administered by a mission-specific office within the state’s Health Care Authority (HCA). | The Medicaid director reports to the director of the HCA; both positions are appointed by the governor. |

As reflected in the table above, there are a variety of ways that comparison states structure their Medicaid administration and its location within the state’s broader reporting hierarchy. Through our comparative analysis of these other state structures and the stakeholder experiences reflected in our public forums, we’ve identified six areas for potential improvement in New York’s Medicaid administration. Those improvements could, in turn, improve outcomes for consumers and providers in the program. Examples of opportunities include:

Staffing and Hiring

Currently, the Medicaid program, as administered by the OHIP under the Department of Health, does not have all the types of staff positions that you would typically find within a large health insurance company handling similar sets of responsibilities. Stakeholders at the forums described the need to work around challenges in the hiring process and their resulting impacts, or the absence of needed expertise. One panelist outlined a three-tier hiring structure—through civil service, professional consultants, and other entities (like foundations)—stating that “the fact that you’ve got this kind of tripartite system just makes it all that much harder to have the people you need, when you need them, where you need them to do the job. So it is the workaround that has worked, but it’s probably not the best approach.” For example, as was discussed at the forums held by the Rockefeller Institute and the United Hospital Fund, there are no actuaries or a dedicated legal team. As a result, the Office often must contract with consultants for such services. Because they are not permanent staff, contracts with consultants can change frequently for a variety of reasons, and as a result, OHIP is not always able to retain valuable institutional knowledge and expertise.

Procurement

The ability to procure sophisticated services—such as creating payment rates, or developing actuarially sound rates, or analyzing large unstructured data from Medicaid data—in a timely way for a large insurance program with multiple benefits and complex payment structures is important. It can take as long as a year and a half for New York State to procure certain core services. More flexibility and input from relevant experts inform those procurements could help accelerate results and time to implementation, and thus benefit consumers and providers in the program.

Data Analytic Capability, Transparency, and Outcome Improvement

Stakeholders participating in the public forum identified further data analysis and transparency as a key area for improvement. As one panelist noted:

We believe that having an understanding of what’s happening in the program through data is really important because we bring, you know, anecdotal evidence, which is very valuable. We think it brings the perspective of people who themselves are being impacted by policy making and administration generally, and understanding what’s happening in the program at a deeper data level is much harder […] when you don’t have access to it. And I would argue that you know, understanding what’s happening in the program is really very important in making advances in the program and figuring out where system changes could be made.

The ability to further capture, analyze, and present comprehensive program data has many benefits to stakeholders. For example, data on the market cost of services helps inform the rates that providers are paid. It also allows consumers to know if they qualify for services and where they can receive those services. It can indicate who is a qualified provider for a specific service and identify when the costs of or demand for services change over time and geography. Data can show which populations are being served, whether people get timely access to services, and what the effect of that service delivery is on health outcomes. It is crucial to have an information technology staff highly trained in the construction, analysis, and presentation of complex healthcare in order to assure program integrity and public accountability.

Compliance with Regulatory and Legal Requirements

Stakeholders highlighted the lack of a program-specific legal team dedicated to Medicaid. Medicaid is governed by a complex set of intertwining federal and state rules and regulations. To change anything in the program, including eligibility requirements, covered services, the amount or duration of those services, and payment rates or payment methodologies, requires legal review and approval. It also requires constant oversight and monitoring to ensure program compliance and integrity. Having a robust and programmatically specific legal and compliance team can be crucial for effective program administration.

Interagency Coordination of Services

Medicaid pays for a significant portion of services that are administered by other agencies outside of the Department of Health. They include programs at the Office of Mental Health, the Office for People with Developmental Disabilities, and the Office of Addiction Services and Supports, all offices that are part of the Department of Mental Hygiene. These programs are considered to constitute a significant portion of overall Medicaid dollars in the program and provide services to some of the state’s most vulnerable residents. Stakeholders noted the further need for coordination across these offices. For example, with respect to federal approval for program changes and the ability to better coordinate services for individuals receiving services from multiple agencies.

Innovation and Demonstration of Impact

One of the few ways that Medicaid programs can innovate is through what is known as an 1115 Research and Demonstration Waiver. Such waivers, depending on their scope, may require an extensive amount of staff time to implement new program structures and changes and evaluate their effectiveness. Yet, such innovation is important given all the changes happening in healthcare more generally. In January 2024, the federal Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services approved one such waiver for New York that the agency called “groundbreaking.” The waiver authorized initiatives that establish sustainable base rates for safety net hospitals that serve the state’s most underserved communities; connect people to critical housing and nutritional support services; enhance access to coordinated and comprehensive treatment for substance use disorders (SUDs); and make long-term, sustainable investments in the state’s healthcare workforce. The application and administration of a Section 1115 waiver is complex, requiring the state to conduct research and to consult with stakeholders, and once approved, a waiver continually incurs administrative costs to implement and manage the new program. Properly carrying out this innovation and demonstrating its impact is important for evolving services in a way that best meets the needs of enrollees in a positive and cost-effective manner. It was also highlighted by stakeholders as particularly important at a time when Medicaid is under heightened scrutiny from the federal government.

Closing

Nearly seven million New Yorkers rely on Medicaid to receive healthcare services. Those enrollees include some of the most vulnerable members of our state population, including people with disabilities, older adults requiring hospital and nursing care, and the lowest-income state residents. Given the size and importance of Medicaid, effectively administering it is an important goal for program enrollees, providers, care managers, taxpayers, and the general public. This blog, the research conducted by the Rockefeller Institute, and the joint forums by the Rockefeller Institute and The United Hospital Fund can help generate useful conversations about the best ways to improve the administration of one of the state’s most important public programs in order to best serve New York’s residents.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Courtney Burke is senior fellow for health policy at the Rockefeller Institute of Government

Oxiris Barbot is president & CEO at the United Hospital Fund

[1] Personal communication with OHIP, June 2024.