This morning, after some confusion and concern in the Trump administration, the president reportedly will make good on his promise and declare the opioid crisis a “public health emergency,” which is different from calling it a “national emergency” as initially floated. However, what the designation means in real terms is unknown. It is unclear if the presidential designation comes with additional funds to combat the crisis and how long the state of emergency will last. At the very least, it sends a powerful message that we are grappling with a complex problem for which we have not found a solution.

The Rockefeller Institute of Government released an April report, The Growing Drug Epidemic in New York, which found that deaths from drug overdoses and chronic drug abuse in New York State increased 71 percent between 2010 and 2015. Opioids are a growing problem not only in New York, but also in many states across the nation. For example, West Virginia had the most drug deaths in the nation, with nearly forty-one deaths for every 100,000 people, while New York had little more than fifteen deaths for every 100,000 people.

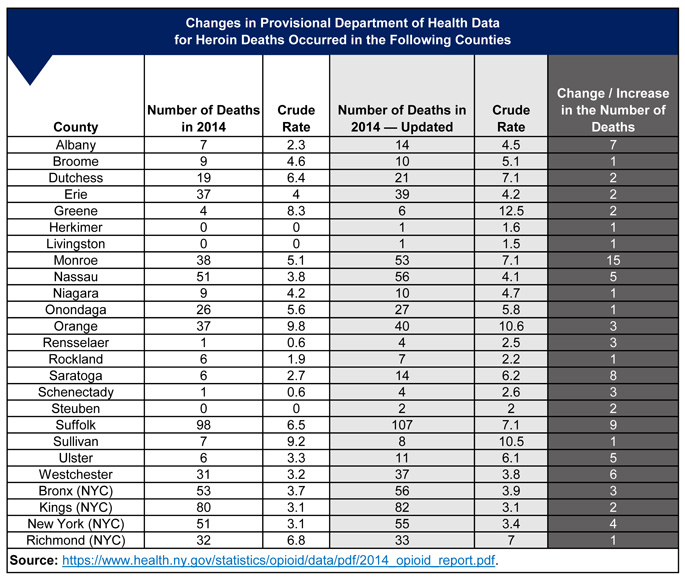

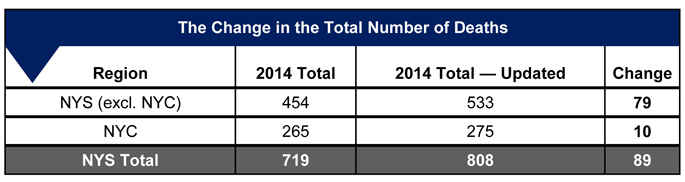

Opioid overdose deaths are the tip of the iceberg for understanding the scope of the epidemic. To provide more context on New York’s epidemic, we followed up with a piece in June that used provisional data from the New York State Department of Health to examine the growing number of heroin overdoses and heroin overdose deaths in New York. In one year, we found a 50 percent increase in deaths related to heroin and a 50 percent increase in emergency room visits due to overdoses.

Yet, as provisional data, we knew there were likely to be changes, and the Department of Health has updated the numbers. There have not been substantial changes in the reported numbers over the past quarter, although we recognize these data have lengthy lag times as counties report their local data. Nevertheless, to assist policymakers, health officials, local community groups, and other stakeholders we will continually update the data going forward on an interactive map found below. We hope this is a useful tool

We are still measuring the health, community, and fiscal impacts of the opioid crisis on communities. But we know hospitals, law enforcement, local government finances, schools, and the families across the nation are feeling the strain. Overdose deaths have gone from alarm to a numbed normalcy. If we are to address this crisis effectively, we must have access to quality data, which is a complicated task given that much of the reporting comes from individual communities. Aggregating local data leads to potential issues, including cases of underreporting or inconsistencies in reporting. In order to address the national health emergency, we must better understand the problem. Good data are the way.