On November 7th, some New York voters may be surprised to see coroner candidates on their ballots. Off-year elections typically have lower voter interest and turnout, and media attention focuses on mayoral races, vacant congressional seats, and special ballot measures such as the upcoming constitutional convention vote. There is limited public discussion about coroner candidates — including why they are elected. In Albany’s 2017 Democratic primary election, considered to be the major race given the city’s large Democratic enrollment, 69 percent of voters selected a mayoral candidate while only 33 percent of the expected coroner votes were completed.[1] Where coroner races are contested, there are fewer votes cast for the coroner candidates compared to the higher profile positions. In the 2016 presidential election, over 99 percent of Herkimer County residents selected a presidential candidate. Although the District 1 coroner seat was uncontested, only 79 percent of voters selected a candidate. The District 3 coroner race was a family match-up between incumbent Vincent Enea and his nephew, Daniel Enea, who had previously been coroner but stepped down for personal reasons before his uncle claimed the seat. In this contested race, 87 percent of voters selected a candidate, which is 12 percentage points lower than presidential votes cast.

In this post, we provide an overview of New York’s coroner/medical examiner system, explain the relevance of coroners to everyday New Yorkers, and provide a guide to help voters select a candidate.

How Do State Death Investigation Systems Work?

Nationally, a decentralized coroner/medical examiner system comprises over 2,300 separate death investigation jurisdictions.[2] New York is one of fourteen states to use a mixture of coroners and medical examiners at the county level.[3] Both coroners and medical examiners investigate deaths, determine the cause of death, and assign the cause of death on death certificates. However, they have very different skills and competencies. Medical examiners are frequently physicians with specialized forensic pathology training that qualifies them to perform autopsies. In contrast, coroners have few training requirements — typical qualifications are being a registered voter, meeting a minimum age requirement, no felony convictions, and completing a training course. Although coroners do not have the specialized forensic pathology training to perform autopsies, they may oversee the work of forensic pathologists.

The roles and duties of the coroner were formally established in medieval England, when the king sent coroners to death scenes to “protect the crown’s interest” and collect taxes. This system was brought to the colonies. Starting in the late 1800s, some states started to replace coroners with medical examiners and impose requirements that trained physicians perform autopsies. Common critiques of the coroner system are a lack of formal training in forensic science and potential conflicts of interest. In smaller counties where being coroner is a part-time job, coroners may have close ties to public safety agencies. For example, coroners who also serve in fire response or emergency management services might be influenced by the chatter they hear on the police radio. In California, the local sheriff serves as the local coroner for over 80 percent of counties. Even if they are insulated from the pressures of public safety agencies, elected coroners may have conflicts when determining the cause of death in cases where the true manner of death is publicly stigmatizing or self-inflicted — such as suicide, AIDS, or opioid overdose. Despite numerous national calls over the past century to replace the coroner system with a medical examiner system, reduce potential conflicts of interest with law enforcement, and improve training and accreditation, there has been limited progress.

Where Does Your County Stack Up?

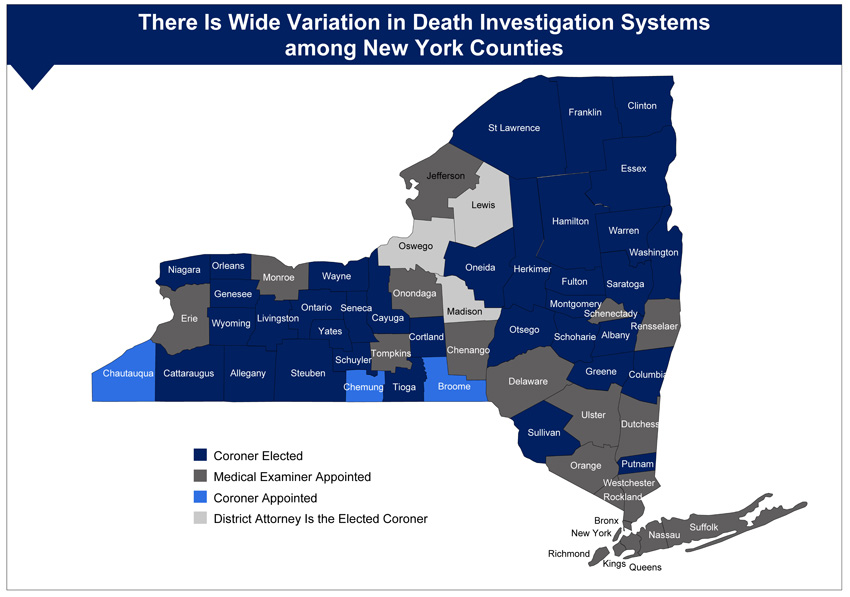

Currently about half of the US is served by coroners, and the other half by medical examiners. In our own analysis to document New York’s local coroner/medical examiner system, we found considerable variation across the state: thirty-eight counties use coroners, twenty-one use medical examiners, and three are affiliated with district attorney offices.[4] Among the coroner counties, three are appointed and the remaining thirty-five are elected. Although two-thirds of all New York counties follow a coroner system (including counties where the district attorney is the elected coroner), most of the state’s population resides in counties with medical examiner systems. Many major metropolitan areas — including Buffalo, Long Island, New York City, Syracuse, and Westchester — are overseen by medical examiners.

How Are Coroners Relevant to Everyday New Yorkers?

Coroners currently have two large missions. As medical detectives, their evidence and testimony in suspicious deaths is critical for the criminal justice system. As public health officers, their work is important for surveillance of diseases, injuries, and terrorism. Although coroners, medical examiners, and death investigators have traditionally served the criminal justice system, they have assumed new roles in larger-reaching public safety, medical, and public health applications in the past few decades.[5]

Collecting and reporting high quality, unbiased, and timely information on the cause of death is at the core of these missions. Coroners have discretion in determining the cause of death and whether to perform an autopsy. Depending on their county’s structure, they may supervise the work of forensic pathologists conducting autopsies. They may also participate in larger initiatives such as entering information on “unclaimed persons” into the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System (NamUs), upgrading outdated data systems to improve the quality of data and reporting, and advocating for improved professional training and resources.

The work of coroners is critical for improving public health, protecting public safety, improving social justice, and helping families heal.

- Criminal cases — Strong criminal evidence is important for building indisputable cases against perpetrators and exonerating the innocent. An in-depth NPR/ProPublica series documented several law enforcement brutality and neglect cases where the death was incorrectly documented as having natural causes, resulting in officers not being charged. It also detailed other violent death cases where autopsy errors led to wrongful convictions; and where there were incomplete autopsies such as cremating a corpse before a murder determination, and missing a bullet lodged in the jaw of a corpse pulled from a river.

- Grieving and healing processes — Determining the cause of death, particularly when the immediate cause is unclear and for long-standing unsolved “cold cases,” is essential to the grieving and healing processes for families.

- Responding to terrorism and mass fatality incidents — Fatality management services, including recovering bodies, identifying victims, and situation assessments are core capabilities for responding to conventional and chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear (CBRN) terrorism. These capabilities are also critical for mass fatality events such as the Boston Marathon Bombings, the recent Las Vegas shooting, and natural disasters.[6] In these incidents, coroners play an important role in collecting forensic evidence to identify and prosecute suspects, identifying current health threats such as leptospirosis outbreaks in Puerto Rico, and appropriately handling biohazardous material to prevent further contamination.

- Public health practice — Vital statistics data are frequently used for monitoring, evaluation, and public health programming. For example, New York City’s RxStat data collaborative brings together over twenty city, state, and federal public health and public safety agencies to use up-to-date opioid overdose death and other local data to understand the causes and consequence of overdoses and respond more effectively. Where the cause of death is determined to be an infectious disease, it may be necessary for the coroner to communicate with public health agencies so that close contacts, healthcare workers, or law enforcement personnel who have been in contact with the deceased individual may be notified.[7]

- Improving the quality of care — Vital statistics data can be combined with clinical data to document systemic quality of care issues, evaluate the effectiveness of local quality improvement initiatives, use hot-spot analysis to identify providers or facilities with disproportionately high death rates, and identify trends such as increased suicide rates. Timely forensic evidence can also assist with investigating suspicious deaths in nursing homes and other healthcare facilities.

How Can Voters Evaluate Coroner Candidates?

Long-standing debates over replacing coroner systems with medical examiner systems, improving quality through accreditation and training, and enhancing system performance are likely to continue. In the meantime, irrespective of the relative merits of elected coroners, New Yorkers may see coroner candidates on their ballots. For these voters, it is important to carefully review the candidates’ backgrounds and visions, rather than relying exclusively on endorsements.

In Albany County’s primary race last September, Francis Simmons’ personal statement included a vision to modernize reporting, move towards e-filing of death certificates to fix the backlog of cases, and strategies to improve professional training. Paul Marra described his long-standing support for legislation on mandatory coroner/medical examiner training. As the incumbent, Marra is a board-certified medicolegal death investigator, has been highly active in pursuing state and local legislation to be trained in death investigation, and has completed trainings in mass fatality incidents. In the Vote411 Voter Guide, none of the other candidates mentioned issues related to data integrity, and instead focused on their professional experiences interacting with bereaved families as funeral directors. Yet among these Democratic primary candidates, the Working Families party endorsed Paul Marra and Benjamin Sturges, III (a funeral home director and community police officer), who both won the vote. (Two coroner seats are available.) Although we cannot determine the exact reasons for voter preferences, we imagine that most voters looked at political party endorsements or likeability. These candidates will be facing off against Republican Scott Snide, a retired Albany Police Department officer whose statement lists his extensive professional experience and training in forensic investigation, emergency services, and terrorism/bioterrorism intelligence and response.

We do not endorse any particular candidates here, but encourage readers to make informed decisions by reviewing their candidates at the County Boards of Elections gateway and the Vote411 Voter Guide. Relevant factors for coroner decisions are: educational qualifications, completion of special training courses in relevant areas such as hazmat training and crime scene investigation, commitment to improving professional training and strengthening the death investigation infrastructure, potential for making unbiased decisions in suspicious or publicly stigmatizing deaths, and visions for improving the quality and timeliness of death data. These are far more relevant than voting along party lines.

[1] Albany voters can vote for two candidates. The expected ballots were calculated as the total ballots cast multiplied by two.

[2] The background information on the history and current state of the coroner/medical examiner system is largely drawn from two national reports: National Research Council, Strengthening Forensic Science in the United States: A Path Forward (Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2009), https://www.nap.edu/catalog/12589/strengthening-forensic-science-in-the-united-states-a-path-forward;and Institute of Medicine, Medicolegal Death Investigation System: Workshop Summary (Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2003), https://www.nap.edu/catalog/10792/medicolegal-death-investigation-system-workshop-summary.

[3] The other states use centralized medical examiner systems (sixteen states and the District of Columbia); county- or district-based medical examiner systems (six states); county-, district-, or parish-based coroner systems (fourteen states), and state medical examiners (twenty-five states). Additional details about each state’s coroner/medical examiner laws, including qualifications, terms of office, and training, are compiled on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s public health law website.

[4] We collected data from the websites of county-level boards of elections, district attorney offices, local health departments, and coroner or medical examiner offices. We also directly contacted individuals and organizations via email and telephone to verify information. Historical election results and candidates’ information were reviewed when available. The New York State Association of County Coroners and Medical Examiners and the New York State Department of Health’s Office of Public Health Practice maintain lists of organizations. However, we did not rely on this information exclusively. Coroners and medical examiners are not required to join the professional association, and the health department no longer maintains a current registry of organizations because they no longer reimburse the local health departments that employ coroners or medical examiners.

[5] Randy Hanzlick, “Medical examiners, coroners, and public health: a review and update,” Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine 130, 9 (2006): 1274-82.

[6] For a more detailed overview of core capabilities for terrorist and mass fatality events, see: Bryan R. Early, Erika G. Martin, Brian Nussbaum, and Kathleen Deloughery, “Should conventional terrorist bombings be considered weapons of mass destruction terrorism?,” Dynamics of Asymmetric Conflict 10, 1 (2017): 54-73.

[7] Hanzlick, “Medical examiners, coroners, and public health: a review and update.”