This week, President Trump unveiled his Made in America campaign to promote products manufactured in the United States. Perceived unfair trade deals helped propel Trump into the White House on the backs of middle-class economic anxiety. Calling it the “worst trade deal ever,” then-candidate Trump raged about the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), the Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP) Agreement, and others.

Trump’s “America First” position on trade had broad appeal on the political Right and Left, though polling suggests a split nationally. Trump capitalized on the anxieties of working-class Americans, many of whom were facing the negative effects of free trade from job losses. Trump’s opposition to free trade helped in the Republican primaries. Polls showed 85 percent of Republicans believed free trade deals cost the United States jobs. Trade deals dogged Hillary Clinton in the Democratic primary against Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders, as well as in the general election against Trump. Trump was to the left of Clinton on trade and Bernie Sanders had already pushed Clinton to be more wary on free trade in the primaries. Trump continued the attack, repeatedly excoriating Hillary Clinton on her past support of free trade on the campaign trail.

To show a different, more aggressive approach to protect American jobs from the iniquities of free trade and globalization, one of the first things Trump did after winning the election was to work out a deal to keep 1,000 jobs at a Carrier plant in Indiana rather than having them go to Mexico.

So far, so good.

However, reality set in fairly quickly. The jobs deal President Trump trumpeted as a major success has run into the realities of the global economy where 600 Carrier employees at the Indiana plant are slated to be laid off. And there was more trouble on the trade front. When Mexico refused to agree to pay for his border wall, President Trump floated a 20 percent import tax on Mexican products. Trump’s proposal was met by stiff resistance, because the tax ultimately would have cost Americans more for goods and products.

President Trump has even backed off on pulling out of NAFTA — the “worst trade deal ever” — for the time being. It appears that even the president recognizes that simply ending NAFTA could have unknown economic consequences.

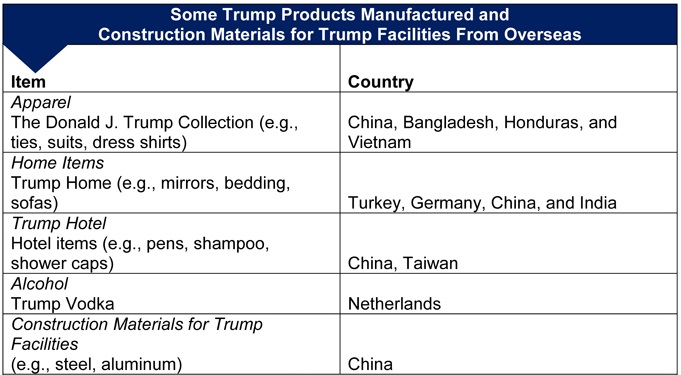

More striking, however, is the juxtaposition of President Trump with businessman Trump. If one looks at Trump’s businesses, a different picture of his behavior on trade emerges. Many of his products — ties, suits, shirts — are manufactured in low-wage countries, like China. To businessman Trump, it makes sense, and free trade supporters note that it drives down the cost of products for American consumers.

Call it Trump against Trump.

That’s not to say President Trump is wrong. His rhetoric connects with the harsh reality facing many working-class Americans. It’s just that businessman Trump is exacerbating their difficulties.

Whether we want to face reality or not, as Thomas Friedman said, the world is flat. Technology and other factors have changed the manufacturing landscape, with lines of geographic demarcation continuing to blur. What is an American company versus a Japanese company, when companies like Toyota have a number of manufacturing facilities in the United States and General Electric has a number of manufacturing facilities overseas? The global marketplace is a complex, interwoven system that isn’t easily described as “us” versus “them.”

The problem may lie in Trump’s solutions and his actions as a businessman. Democrats, like Bill Clinton, and Republicans in Congress embraced the changing landscape through open/free trade. Either companies are flocking to low-wage markets or replacing American workers with machines. There are obvious issues that both political parties are still grappling with, and these issues don’t just affect national actors.

The fact is trade policies and globalization have a dramatic effect on state fiscal conditions too. In an ever-increasing competitive environment, states are competing with finite tax dollars to lure companies and their jobs into their communities.

The competition is fierce. States that are adapting are doing well, while those stuck in the previous manufacturing age are not. And trade opportunities are a primary concern of states. During this past week’s National Governors Association meeting focused on trade, in an unprecedented move, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau spoke of looking for states as partners.

Despite the rhetoric about free trade, the United States has in the past, and continues to, pursue policies to protect American trade interests and tax dollars. In New York, there has been legislation in the past to prevent state tax dollars from being used as economic incentives to companies that outsource jobs to other countries. At bottom, elected officials may not be able to stop outsourcing, but the government shouldn’t subsidize it. And just this year in New York, a trade-union priority, the Buy American Act, which gives preference to American steel in construction contracts, was enacted.

As a nation we must take a hard look at how to adapt to the ever-shrinking world, while protecting American workers and ever-dwindling state tax revenue. New job training, focusing on high-tech, high-skilled sectors, and other approaches are needed. Fair trade is a necessary component. Let’s hope our leaders’ ideas AND actions match in that effort.