What is the Green Amendment?

When New Yorkers go to the polls this election day on November 2, they will have the opportunity to vote on the addition of a ‘green amendment’ to the state’s constitution. In the recent Rockefeller Institute report, green amendments were defined as “constitutional provisions that: grant residents an affirmative right to certain environmental conditions; locate those rights under the state bill of rights, rather than elsewhere in the state constitution; and broadly include environmental rights like clean air, clean water, and a healthy environment.” The proposed amendment in New York would ensure that “each person shall have a right to clean air and water, and a healthful environment.”

The passage of a green amendment would serve to give New York residents and organizations standing (the right to bring a case forward) in a court of law to challenge environmental activities on the basis that they transgress their environmental rights. This standing may allow residents to bring lawsuits either seeking redress following a harmful action or an injunction ahead of an action to prevent potential harm. For example, if a hazardous waste facility in your neighborhood was permitted to conduct an activity, you as a resident or member of a relevant group could go to the court and seek an injunction by demonstrating that the potential impact violated your environmental rights by negatively impacting the air quality of the community. Likewise, individuals or groups could have standing to bring a case to prevent the adoption of a new law, if the state legislature passed and the governor signed legislation requiring localities to permit certain facilities or activities, if they can demonstrate those activities or facilities transgress their environmental rights.

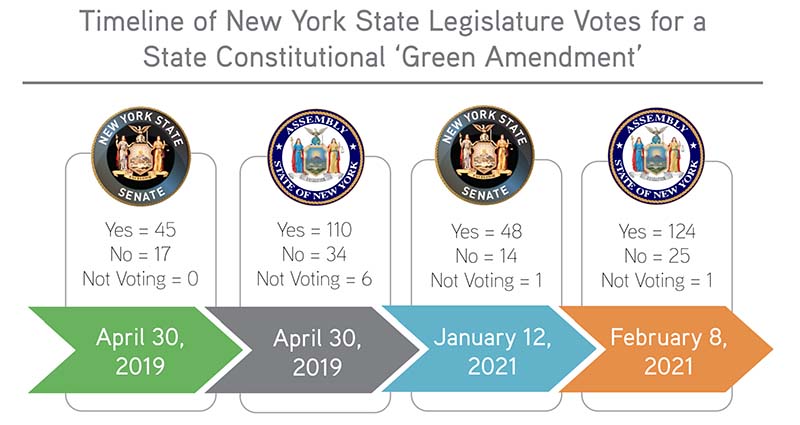

As with any constitutional amendment in New York, the underlying bill had to be passed through both the State Senate and Assembly during two separate legislative sessions before voters can act upon it. The green amendment was first introduced as legislation in 2017. While the bill passed the Assembly during the 2017-18 session, it did not initially pass the Senate. In 2019, following the new Democratic majority in the Senate, Assemblyman Steve Englebright and Senator David Carlucci reintroduced the bill in their respective houses. Since then, it has passed both houses twice by increasing margins and met the requisite threshold to bring it to a public referendum.

Following debate in April of 2019, the Senate passed the bill underlying the amendment by 45 to 17, while in the Assembly passed the bill 110 to 34. During the subsequent legislative session in January and February of 2021, the bill was then passed through both houses again, this time by a slightly higher margin of 48 to 14 in the Senate and 124 to 25 in the Assembly. The bill received unanimous support from Democratic representatives in both houses and was voted for in 2021 by six Republican Senators, seventeen Republican Assemblymembers, and one Independence Party member in the Assembly.

In order for the green amendment to fully be enacted, however, the bill still has to be passed through a public referendum this November 2nd by voters—meaning that New York residents will be invited to have direct input on this amendment and ultimately determine if it will be added to the state’s constitution.

Debating the Advantages and Concerns of a Green Amendment

The potential advantages and concerns related to a green amendment in New York were raised in the legislative debates that took place between 2019 and 2021,[1] as well as in panel discussions, news articles, and opinion pieces or editorials by stakeholder groups.

Early public facing documents from stakeholders and legislative debate transcripts reflect the main arguments from both supporters and opposition groups. Arguments from opponents frame the green amendment with respect to: the specificity of its language or lack thereof; the potential for increased litigiousness or legal duplicativeness; and, the costs to businesses. Whereas proponents of the green amendment tended to highlight: the long-term economic and human health benefits of such rights; the legal significance of ensuring communities can bring cases where harm has or may be caused, particularly for those experiencing the greatest burdens; and, the observation of recent environmental health harms in New York and in the United States.

The proposed amendment in New York would ensure that ‘each person shall have a right to clean air and water, and a healthful environment.’

With respect to the amendment’s potential costs, opponents fear the lack of linguistic specificity and the opportunity for litigious action could have a negative impact on New York’s businesses and increase prices. For example, during debate, minority Assemblymember Phil Palmesano expressed concern that the amendment could increase energy prices for consumers because citizens would be able to target lawsuits against specific generation technologies, such as fossil fuels, or even renewables because “[that particular technology] is infringing on their Constitutional right…”.

Proponents have also framed the amendment with respect to costs, however, asserting that the amendment will actually prevent future or long-term costs. Senator Carlucci, for example, discussed the amendment as a choice between paying smaller upfront costs if the amendment passed or larger deferred costs in its absence:

Look, we could either pay now or we’ll be paying the cost later. And this constitutional amendment is about enshrining those rights so that generations to come, they will be inheriting an environment that’s healthy. There’s a saying: discipline weighs ounces, regret weighs tons. And that’s what we have to do.

In addition to potential long-term savings, proponents have highlighted the advantages of establishing standing for those communities most burdened by harms, particularly environmental justice communities, who generally have fewer resources with which to contend environmental actions. As such proponents have tended to frame the amendment as securing rights for residents of New York and protecting vulnerable communities.

However, there are still unknowns surrounding the proposed amendments’ ultimate impact. As the Rockefeller Institute’s report highlights, the experiences of other states with green amendments show that any potential benefits are likely to be highly dependent on the legal cases that follow enactment.

Green Amendments in Other States—Pennsylvania & Montana

New York would not be the first state to implement a green amendment if voters pass it on Election Day, but it would be the first to do so in decades. State green amendments were first passed in Pennsylvania in 1971 and Montana in 1972 on the heels of the environmental movement of the mid-twentieth century in the United States. These two states are the only states to enact green amendments and enshrine such protections in their bill of rights. However, a handful of other states (Illinois, Massachusetts, Hawaii, and Rhode Island) have also included some environmental provisions in their broader constitutions. The Rockefeller Institute’s report discussed these amendments in-depth with respect to how stakeholders framed the amendments’ potential impacts ahead of its adoption, and whether those potential advantages and concerns were observed after its adoption.

…the experiences of other states with green amendments show that any potential benefits are likely to be highly dependent on the legal cases that follow enactment.

Pennsylvania

Similar to New York, Pennsylvania’s green amendment had to be passed by the legislature twice before being put to a public referendum. The amendment in Pennsylvania, referred to as the Environmental Rights Amendment, states that:

The people have a right to clean air, pure water, and to the preservation of the natural, scenic, historic, and esthetic values of the environment. Pennsylvania’s public natural resources are the common property of all the people, including generations yet to come. As trustee of these resources, the Commonwealth shall conserve and maintain them for the benefit of all the people.

Records reflect that there was little to no opposition in legislative debate to the proposed amendment. During the debate, proponents framed the amendment with respect to future generations and in an effort to avoid existential threats brought on by environmental degradation, as well as in reference to more imminent human and environmental health impacts from pollution being observed at that time. During both the 1969-70 and 1970-71 sessions, the state legislature passed the amendment unanimously. In 1971, voters then ratified the amendment by a margin of 4 to 1.

Despite the broad support for the amendment, its impacts were greatly limited by ensuing court cases. The 1973 Pennsylvania Supreme Court case Payne v. Kassab established a three-part test to determine if an action violated the state’s green amendment. The test asked the following questions:

- Was there compliance with all applicable statutes and regulations relevant to the protection of the Commonwealth’s public natural resources?

- Does the record demonstrate a reasonable effort to reduce the environmental incursion to a minimum?

- Does the environmental harm which will result from the challenged decision or action so clearly outweigh the benefits to be derived therefrom that to proceed further would be an abuse of discretion?

When judges in subsequent cases then utilized these criteria to determine if a suit could be brought against an action, it proved very difficult to meet. As such, the Rockefeller Institute’s report notes that 23 out of 24 cases brought against state actions following Payne did not meet the criteria. This has begun to shift with the decisions in two more recent cases—Robinson Township et al. v. Commonwealth (2013) and Pennsylvania Environmental Defense Foundation v. Commonwealth (2017). Both of these cases related to oil and gas development, namely with respect to fracking. In Robinson Township the court ruled that parts of a law preempting local control over the permitting of oil and gas development was unconstitutional. While in the case of Pennsylvania Environmental Defense Foundation the court determined that the state could not divert certain funds raised from oil and gas development for purposes other than environmental conservation. These decisions worked to first narrow and then overturn the application of this three-part test, opening the door to new cases through which Pennsylvania’s green amendment might be more fully felt.

Montana

Unlike in New York and Pennsylvania, Montana initially passed its green amendment through a constitutional convention before it was voted on as part of a broader public referendum with a host of other measures passed by the convention. The final amendment that was adopted by the convention and then by voters, which include provisions beyond environmental rights, reads:

All persons are born free and have certain inalienable rights. They include the right to a clean and healthful environment and the rights of pursuing life’s basic necessities, enjoying and defending their lives and liberties, acquiring, possessing and protecting property, and seeking their safety, health and happiness in all lawful ways. In enjoying these rights, all persons recognize corresponding responsibilities.

Records of the convention’s proceedings reflect that there was broad consensus on passing an environmental amendment of some kind, but little on how it should look. As in Pennsylvania, the debate over the amendment in Montana tended to frame concerns regarding future generations. And, like the more recent debate in New York, delegates in Montana were concerned with how specific or broad the amendment’s wording should be. Unlike in New York, however, it was those stronger proponents arguing the need for more specific language using the terminology “clean and healthful.”[2] The relative specificity/vagueness was of concern to delegates with respect to which branches of government might end up with further control over or responsibility for the environmental provisions. Those opposed to including the language “clean and healthful,” argued that it might give too much power to the courts to interpret their meaning, rather than to state agencies or the legislature. Consequently, the convention included provisions under a separate Environmental and Natural Resources section, in which they vested further authority in the legislature to “maintain and improve a clean and healthful environment in Montana for present and future generations.”

The relative specificity/vagueness was of concern to delegates with respect to which branches of government might end up with further control over or responsibility for the environmental provisions.

As in Pennsylvania the impact of Montana’s green amendment was significantly limited by court decisions in the first few decades following its adoption. In 1976, the state supreme court ruled against a resident-led conservation group, in Montana Wilderness Association v. Montana Board of Health and Environmental Science. The Association attempted to bring a suit to prevent a construction project based on an inadequate environmental impact assessment. The court, however, found that the residents in that case did not have standing to bring a suit despite the enactment of the green amendment, overturning their own earlier ruling on the case. Just a few years later in 1979, in Kadillak v. Anaconda the court further limited the application of the green amendment, finding that the state’s environmental impact assessment process—as outlined in the Montana Environmental Protection Act (MEPA)—could not be challenged based on the constitutional provisions of the green amendment because it was passed after MEPA. It was not until 1999, that the amendments application began to shift following Montana Environmental Information Center v. Department of Environmental Quality. Among other things, the ruling in that case determined that the environmental rights provided by the green amendment were “both anticipatory and preventive.” And, more recently, in Park County Environmental Council & Greater Yellowstone Coalition v. MT DEQ & Lucky Minerals Inc. (2020), the court struck down a state constitutional amendment passed by the legislature that prohibited injunctions to halt projects under MEPA.

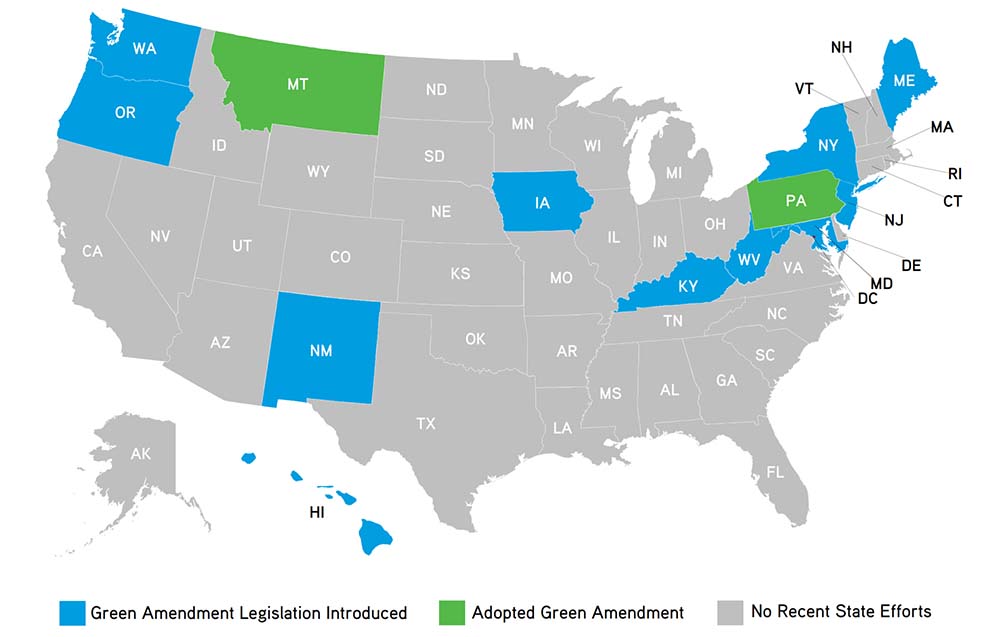

What other states are considering Green Amendments now?

Building on the shifts that such case law has provided, advocates and legislatures in other states have introduced proposals for green amendments across the U.S. In addition to New York, legislation has been introduced in 10 other states in recent years, including Hawaii, Idaho, Kentucky, Maine, Maryland, New Jersey, New Mexico, Oregon, Washington, and West Virginia. Arizona, Connecticut, Colorado, Delaware, and Florida have also expressed a growing interest in developing their own amendment language proposals.

New Jersey’s amendment language was first introduced in 2017 alongside New York’s. The proposed amendment has bi-partisan support as Assemblymen John Mckeon (D) and Daniel Benson (D), with Senators Linda Greenstein (D) and Christopher Bateman (R), co-sponsored these resolutions. As in Pennsylvania’s amendment, the language of the bill details how the state would act as a trustee of public natural resources and guarantee environmental rights to residents, and that the rights would be self-executing and, therefore, not in need of further legislation to make it effective.

In addition to New York and New Jersey, environmental groups expect that other states—including Maine, Hawaii, and New Mexico—may be on their way to advancing green amendment legislation in 2022. In Maine, for example, Senator Chloe Maxmin (D) introduced resolution LD 489 in March 2021, known as the “Pine Tree Amendment.” Maxmin’s legislation would “amend the constitution of Maine to grant the people of the state a right to establishing a clean and healthy environment and to the preservation of the natural, cultural, recreational, scenic and healthful qualities of the environment.” This language reflects that of Pennsylvania’s green amendment in that it includes qualities beyond cleanliness and healthiness, such as those scenic ones. Like proponents in New York, Senator Maxmin echoed the economic and environmental health benefits that this amendment could have, such as improving the job sector for fishermen, farmers, foresters, and guides, while noting the intent to “hold [the] government accountable” for all Mainers. LD 489 was last sent from the State Senate to the House on April 28th, 2021. As it is a constitutional amendment, the resolution will need a 2/3 approval by the House and Senate before being put before Maine voters in a public referendum, but it is not on the ballot yet.

States That Have Introduced Green Amendment Legislation

Conclusion

Ultimately, voters will get to decide if New York adopts a green amendment to the state constitution this November. While the experiences of Pennsylvania and Montana cannot tell us exactly what will happen in New York, they can highlight dynamics that may affect the impact of the green amendment on the state.

In both cases, court precedents following the green amendments’ adoption heavily influenced the impact for decades to follow, curtailing the ability of individuals and groups to bring cases to enforce their environmental rights. Given the experience in those states, New Yorkers might anticipate that the concerns of opponents regarding costs to business and litigation are not likely to be as significant as stated in the long-term. Likewise, the hopes of proponents regarding the protection of human and environmental health through the adoption of these rights may not see immediate changes until and unless case law takes up questions such as the determination of standing, the application of the amendment to processes outlined under prior statutes or in anticipatory cases. More recent case law in Pennsylvania and Montana may, however, indicate a shift in how the courts are treating green amendments such that their benefits will be more swiftly realized. Before that happens, it will be up to New Yorkers to decide how they will approach the upcoming vote and whether or not the green amendment ultimately becomes law.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Laura Rabinow is deputy director of research at the Rockefeller Institute of Government

Abigail Guisbond is a graduate research assistant at the Rockefeller Institute of Government

[1] Debate on the bill took place on April 30, 2019, and January 12, 2021, in the Senate; and on April 30, 2019, and February 8, 2021 in the Assembly.

[2] It should be noted, however, that the more specific language ultimately adopted by Montana more closely mirrors the language in New York’s proposed amendment.