For the past decade, the Association of School Business Officials of New York (ASBO New York) has hosted an annual School Finance Symposium on cutting-edge topics ranging from the Foundation Aid Formula to unfunded mandates. For this year’s symposium, the Association focused on the state’s new zero-emission school bus mandate that came out of the 2022-23 enacted state budget. The event was held on October 4th in partnership with the Rockefeller Institute of Government.

Key Takeaways

- The transition to a zero-emissions fleet will be a long-term project that offers substantial benefits for students, school districts, and their communities.

- A full transition to zero-emissions technology is a substantial undertaking, but can be realized with further resources and planning for logistical challenges.

- Some aspects of financing and resources to support the transition are not yet fully clear.

Symposium Overview

David Lombarbo, host of WCNY’s The Capitol Pressroom, moderated the event, which featured six speakers on two panels.

Panel One

“Tech and Trends in the EV School Bus Market”

— Matt Stanberry, Highland Electric Fleets

“Electric School Bus Infrastructure”

— Adam Ruder, NYSERDA

“Electric School Bus Momentum”

— Sue Gander, World Resources Institute

Panel Two

“Zero Emissions School Bus Update”

— Brian Lafountain, Transportation Advisory Services (TAS)

“Electric School Buses in New York State”

— Laura Rabinow, Rockefeller Institute of Government

“Why Electric School Buses”

— Conor Bambrick, Environment Advocates New York

The Zero-Emission School Bus Mandate

In April 2022, New York’s Enacted 2022-23 State Budget included a requirement that, by 2035, all student transportation be done with zero-emission vehicles, a policy first introduced in Governor Kathy Hochul’s 2022 State of the State address.

Under the law, all school district purchases or leases of new vehicles for pupil transportation must be zero-emission by July 1, 2027. Private transportation companies that provide contract transportation are also subject to the mandate for any vehicle that transports students.

School districts may request a delay in the implementation of the July 1, 2027, deadline and be granted an extension for up to two years, but by July 1, 2029, all purchases and leases by school districts or transportation contractors will need to be electric. On July 1, 2035, when the mandate is fully in effect:

- all district-owned school buses will be electric; and

- all contractors providing transportation services to a school district will only use electric school buses in fulfilling the contract.

The law also includes a requirement that electric school buses should be assembled in the United States with parts that were also made domestically. The commissioner of education has the ability to waive that requirement in response to market conditions. The legislation also considered the potential impact of district employees who currently operate and service nonelectric vehicles. Labor provisions of the new law require school districts and private contractors to put together detailed workforce development plans that ensure that no employee who agrees to retraining will face being laid off.

In order to support school districts in this large-scale transformation, the New York State Energy and Research Development Authority (NYSERDA) has been tasked with providing technical assistance on electric school buses and related infrastructure to school districts, contract transportation operators, and public transportation service providers. During the symposium, panelist Adam Ruder, assistant director of clean transportation at NYSERDA, shared details about the Authority’s plans to create a user-focused guidebook for school districts and operators as part of its overall work to develop the zero-emission school bus roadmap.

NYSERDA will also support school districts in applying for public and private grants to support efforts in compliance with the mandate.

Potential Benefits of Zero-Emission School Buses

A fully zero-emission school bus fleet offers environmental, public health, and financial benefits for local communities, school districts, and the students they serve. There are nearly 500,000 school buses in use by districts across the United States that transport approximately 26 million children every day. About 95 percent of those buses currently run on diesel fuel to the tune of 800 million gallons each year.

Panelist Conor Bambrick outlined the detrimental human and environmental health impacts associated with exposure to diesel exhaust from the existing fleets of largely nonelectric buses. In particular, he highlighted the negative impacts on cognitive and respiratory health in children and how emissions inside a school bus can exceed surrounding areas by five to ten times.

Diesel engines emit fine particulate matter that contains hundreds of chemicals, causing air pollution that contributes to both negative health impacts and climate change. Diesel-based pollution from vehicles is disproportionately felt by communities of color and low-income communities in the US, and school buses are no exception, as low-income students disproportionately ride the bus to school and Black students are much more likely to have longer bus routes resulting in greater exposures. This inequitable distribution of and exposure to air pollution and related health impacts makes school bus electrification an environmental justice (EJ) concern.

In addition to these more direct human health impacts, diesel emissions also contribute to increased ground-level ozone, acid rain, and to broader climatic change. The transportation sector in the United States is responsible for 27 percent of total greenhouse gas emissions (in 2020). Similarly, transportation is responsible for 28 percent of GHG emissions in New York State (in 2019). Most of the emissions from this sector, over 90 percent, are the result of burning fossil fuels (gasoline and diesel) to run vehicles.

While the production of electric school buses still generates greenhouse gases through the development of materials and manufacturing processes, their overall output is lower than other types of buses. Moving forward, the continued transition towards renewable energy sources in New York, under the goals of the landmark Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act (2019), will further magnify the environmental benefits of electric school buses. The electricity used to power the school fleets will draw on less polluting energy sources for power as the state’s energy sources transition. In addition, panelist Matt Stanberry noted that EV buses may themselves be able to contribute to lowering the use of nonrenewable sources, by providing energy back to the grid at times of peak demand as vehicle-to-grid (V2G) technologies further develop, especially as buses are not as widely in use when electricity demand peaks during late afternoons/early evenings in the summer. However, the viability and economics of V2G are not currently clear.

In addition to the detrimental health impacts associated with diesel exposure, are the direct and indirect costs associated with those health impacts, as well as the short- and long-term potential cost-savings associated with transitioning to electric vehicles. Electric vehicles are more efficient than traditional fossil fuel-based vehicles, as they convert 77 percent of the electrical energy to power the vehicle, compared to 12-30 percent. The costs associated with that electricity usage are also typically more stable than petroleum-based fuels.

What’s Needed to Make the Transition

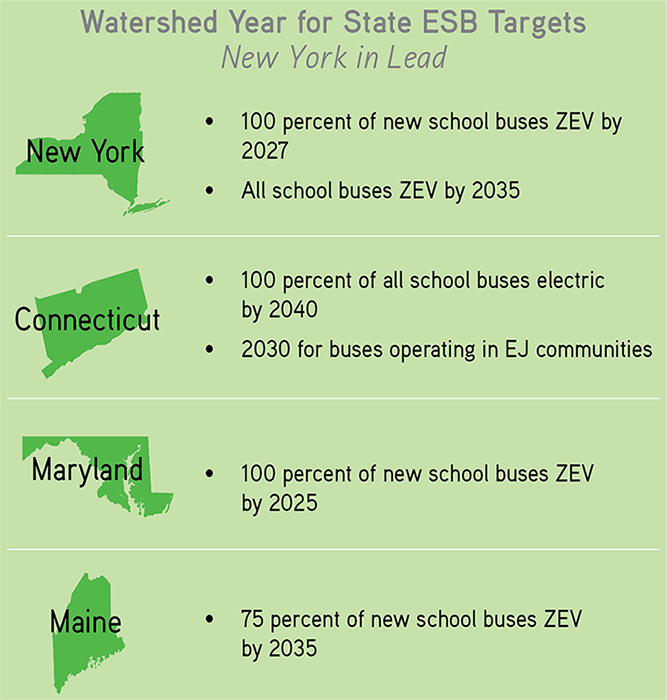

Right now, only approximately 3 percent of school buses across the US are electric, according to panelist Sue Gander. Gander noted, however, that school districts in 38 states have already deployed or committed to EV buses, with four states—New York, Connecticut, Maryland, and Maine—setting goals for new school buses to be electric.

There are a number of considerations for districts in New York that were identified at the symposium as they make this transition to an all-electric school bus fleet. These include: the availability of vehicles and related technologies and their relative capacities; the costs associated with those technologies and the related resources, funding structures, or incentives for them; the existing and required infrastructure needed to support the adoption of those new technologies; and the human resources and training necessary to operate and maintain those technologies (among others).

While the new law in New York State more broadly requires zero-emission vehicles (ZEVs), the only currently available technology to meet this requirement are plug-in electric vehicles. A typical diesel school bus costs approximately $100,000 – $200,000, while a similarly sized electric school bus is in the $300,000 – $400,000 range (see table below, which was part of panelist Matt Stanberry’s presentation). Beyond the purchase of the vehicles themselves, the transition also requires installing charging stations and supporting infrastructure. Existing electric school buses have a large battery pack that is charged through connection to an external power source or charging station. Because of the strategic complexity of charging, the software underlying a district’s charging system can impact overall performance. Beyond those upfront costs, drivers and mechanics will need training on these new technologies.

Electric School Buses Available

Three logistical challenges related to charging infrastructure were discussed by districts and panelists at the symposium—the time necessary to charge vehicles, the space and underlying infrastructure needed to charge them, and the vehicle’s range. Unlike traditional diesel engines that can be refilled in minutes, the time to charge an electric school bus can range significantly from 1 to 13 hours, with shorter charging times being accomplished by more expensive chargers that can cost up to $40,000 each. The current range for Type-C school buses (the traditional, full-size bus) is generally 100 to 200 miles. However, operating conditions, including temperature and elevation, can significantly impact the range. While these limitations present a constraint that must be addressed in planning for full electrification, multiple panelists pointed out that nearly every school district has student routes that can be well served through current electric school bus technology. This gradual transition will allow districts to learn from direct experience, while also allowing for technological development.

Panelist Brian Lafountain noted the difficulties in fully transitioning all student transportation to zero-emission vehicles, as school districts routinely provide out-of-district transportation to students in numerous scenarios. These include private and charter school students, special education placements, homeless and foster students, field trips, and athletics.

Financing the Transition

The structure of school finance in New York State makes it difficult for school districts to undertake these challenges. For the past decade, school districts have faced a tax cap that limits levy increases to the lesser of 2 percent or inflation, after adjusting for district-specific circumstances. School districts also receive Transportation Aid from the state that reimburses a share of bus-related contracts, purchases, and operations. The new law makes these kinds of expenses related to electric school buses eligible under Transportation Aid. The state’s share varies inversely with district fiscal capacity, providing more resources to poorer school districts. Even for districts with relatively high Transportation Aid ratios, however, the transition will still require significant local expense.

These upfront costs can be at least partially offset by federal and state funding or incentives. For example, the federal Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (2021) includes $5 billion for clean school buses over five years, through the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Clean School Bus Program, for which state and local governments along with school districts and charter schools are eligible to apply. The more recent Inflation Reduction Act (2022) also made school buses eligible for funding through the EPA’s new Clean Heavy Duty Vehicles Program. And, in addition, New Yorkers voted to pass the $4.2 billion Clean Water, Clean Air, and Green Jobs Environmental Bond Act of 2022 this November 8th. That funding includes $500 million for transitioning school district transportation to zero-emissions under the Climate Change Mitigation account.

Conclusion

The 2022 School Finance Symposium made clear that New York State is at the forefront of the movement to transition pupil transportation to zero-emission vehicles. Whether school districts directly provide transportation or use contractors, the scope of the change will require long-term planning and continued external financial and technical supports in order to successfully achieve the goal of decarbonizing our school bus fleets across the state.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Andrew Van Alstyne is director of education and research at the Association of School Business Officials New York

Laura Rabinow is deputy director of research at the Rockefeller Institute of Government