Universal broadband access has been a stated public goal of the US since the Telecommunications Act of 1996. In the past 13 years, the federal government has spent roughly $85 billion in pursuit of universal access and closing the digital divide, the gaps in access to and use of the internet and other information technologies between certain groups of people. Millions more have been spent by state governments. Despite these investments, the US still does not have universal broadband and the digital divide persists.

Households without internet access miss out on the numerous and well-documented benefits broadband provides. As written in the recently enacted federal Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), “[a]ccess to affordable, reliable, high-speed broadband is essential to full participation in modern life in the United States,” a sentiment that predates the COVID-19 pandemic but became incontrovertible in the face of lockdowns and social distancing mandates. Among many other uses, broadband allows students to attend school remotely, makes it easier for job seekers to search for jobs, and enables patients to use telehealth services. The IIJA has allocated another $65 billion towards expanding broadband access and affordability. But will these funds be effectively leveraged to increase internet access and use and bring us meaningfully closer to closing the digital divide?

While our first article on broadband focused on a general overview of state and local policies and our second on municipal broadband and cooperatives, this article analyzes policies related to affordability. We will focus on policies to address other barriers to adoption in a subsequent piece.

Broadband Definitions

Broadband. High-speed internet service defined by the Federal Communication Commission’s (FCC) as having minimum download speeds of 25 megabits per second (Mbps) and upload speeds of 3 Mbps.

Broadband Access. The ability to connect to high-speed internet both in terms of broadband service being available for purchase and a household or organization’s ability to adopt broadband.

Broadband Availability. Whether an area or household is wired to be able to connect to high-speed internet.

Broadband Adoption. Residential subscribership to high-speed internet access.

Broadband Affordability. A household’s ability to afford to adopt broadband.

Digital Divide. The gap in access to and use of the internet and other information technologies between different population groups.

Digital Equity. A condition in which all individuals and communities have the technological capacity necessary for full participation in today’s economy and society.

Digital Inclusion. Activities that ensure that all individuals and communities have access to the internet and other information technologies.

Digital Literacy. Defined by the American Library Association as an individual’s “ability to use information and communication technologies to find, evaluate, create, and communicate information, requiring both cognitive and technical skills.”

Why Haven’t Investments Achieved Universal Access?

To date, public funds for universal internet access and use have primarily been spent on expanding the deployment of broadband infrastructure to increase the availability of high-speed internet in areas where private sector internet service providers (ISPs) have failed to do so. But universal availability is only part of the equation. The other part of that equation is adoption.

In the past 13 years, the federal government has spent roughly $85 billion in pursuit of universal access and closing the digital divide…

While availability refers to an area being wired for broadband service, adoption is traditionally defined as residential subscribership to high-speed internet access. Just because a household has the option of purchasing a home broadband subscription does not mean that it will do so or can do so. As of 2019, broadband that meets the Federal Communications Commission’s (FCC) minimum speed standard has been deployed to over 95 percent of Americans, yet the adoption rate of broadband stood at less than 70 percent of households.

Of the households that have not adopted broadband despite it being available in their area, roughly half—18 million households—forego a subscription because they cannot afford it, a finding that has been replicated by organizations such as Education Superhighway, the National Digital Inclusion Alliance (NDIA), and Pew Research Center. This hardly comes as a surprise given the relatively high cost of a residential internet subscription in the US—$68 per month on average, according to one estimate. Moreover, one-third of people also cite the cost of a computer as a reason for non-adoption, according to survey data from Pew. In contrast, only one quarter cite lack of access or low speed as a reason. Other common reasons for non-adoption include a lack of awareness of the benefits of broadband, unfamiliarity with digital devices, and insufficient digital skills and digital literacy, which the American Library Association defines as “the ability to use information and communication technologies to find, evaluate, create, and communicate information, requiring both cognitive and technical skills.”

New Policies for Closing the Digital Divide

Federal, state, and even local governments are beginning to put more emphasis on digital inclusion and digital equity. The former defined as activities that ensure that all individuals and communities have access to the internet and other information technologies, and the latter defined as a condition in which all individuals and communities have the technological capacity necessary for full participation in today’s society and economy. This has come with a recognition that adoption and affordability are major hurdles to achieving these goals.

At the federal level, the IIJA includes a requirement that ISP grant recipients offer a low-cost affordable plan. Moreover, Congress recently allocated billions of dollars for broadband subscription subsidies through the FCC’s Emergency Broadband Benefit (EBB) and Affordability Connectivity Program (ACP). Some states, such as Kansas with its Broadband Partnership Adoption Grant, are following suit with their own subsidies. Other states are putting resources into other types of adoption efforts such as California with its Broadband Adoption Fund. At the local level, municipalities with publicly owned broadband networks or public-private partnerships are creating low- or no-cost plans for low-income households.

With the IIJA funding, which includes $42.5 billion for the Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment (BEAD) Program that gives money directly to states, governments at all levels can leverage this opportunity not only to build out new broadband infrastructure, but also to promote adoption and make broadband more affordable.

The Gap Between Availability and Adoption

According to the FCC, as of 2019, the most recent year for which there are data, 95.6 percent of Americans had coverage of fixed terrestrial broadband that met the FCC’s minimum speed standard of 25 megabits per second (Mbps) download and 3 Mbps upload (though this figure is widely believed to be overstated). However, 69.4 percent of households have adopted broadband that met this 25/3 Mbps standard.

Availability vs. Adoption Rates

SOURCE: Fourteenth Broadband Deployment Report (PDF) (Federal Communications Commission). Note that deployment rates are based on individuals while adoption rates are based on households.

For larger households, a 25/3 Mbps subscription may be insufficient given that having more users accessing the same network simultaneously requires greater bandwidth and faster speeds. Yet adoption rates for higher speeds are even lower. Fixed terrestrial broadband with 50/5 Mbps speed has an adoption rate of 64.8 percent while 100/10 Mbps has a rate of only about 50 percent. The adoption rate for the slower speed of 10/1 Mbps, which does not qualify as broadband according to FCC standards, is slightly higher at 77 percent, but such a low speed, while better than nothing, is ill-suited to most modern applications of the internet, such as video streaming, video conferencing, and transferring large amounts of data quickly. Meanwhile, over 17 percent of households do not have internet of any kind beyond dial-up, according to the 2019 American Community Survey (ACS).

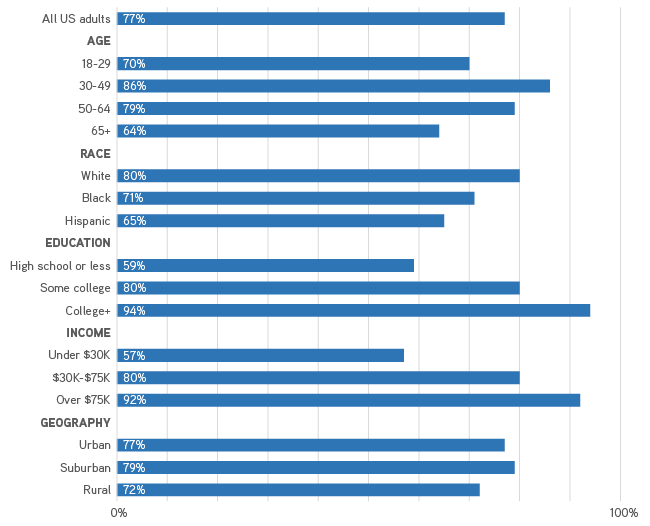

Home broadband adoption rates also vary tremendously across different demographics, which is perhaps the starkest indicator of the digital divide. According to survey data from Pew Research Center, white adults (with an 80 percent adoption rate) are more likely to have broadband at home than Black (71 percent) or Hispanic (65 percent) adults, while adults living in urban (77 percent) and suburban (79 percent) areas are more likely to adopt broadband than those in rural areas (72 percent). The largest disparities are found between those with different levels of education and income. The gap in adoption rates between adults with a college degree (94 percent) and those with a high school degree or less (59 percent) and the gap between those making over $75,000 per year (92 percent) and those making under $30,000 (57 percent) are both 35 percentage points.

Broadband Adoption Rates by Demographic Among US Adults

SOURCE: Mobile Technology and Home Broadband 2021 (Pew Research Center). Note that Pew’s surveys do not specify that home broadband speeds must meet the FCC minimum 25/3 Mbps standard.

Policy Solutions for Increasing Affordability

In recent years federal, state, and local governments have started recognizing the importance of affordability and adoption. Most states’ strategic broadband plans now include goals and recommendations about how to make internet subscriptions more affordable and increase adoption in other ways such as focusing on digital literacy and education about broadband’s benefits. For example, Arizona’s strategic plan includes goals of ensuring that “[b]roadband is accessible and affordable,” and that “[c]itizens understand the impact of broadband and promote adoption.”

Many states—along with the federal government and numerous localities—have begun to implement policies to achieve those goals. Policies related to affordability generally fall into three categories:

- Direct subsidies to consumers;

- Incentivizing or requiring ISPs to offer affordable plans and promote adoption;

- Offering low- or no-cost plans through municipal broadband or public-private partnerships.

We will focus on other efforts to promote adoption, such as funding digital literacy and educational campaigns, in a subsequent article.

Making Residential Broadband More Affordable Through Direct Subsidies

The simplest way to make broadband more affordable is to subsidize residential subscription service. While the federal government has been subsidizing ISPs (as well as schools and libraries through the FCC’s E-Rate Program) since 1996, it did not start subsidizing consumers directly until 2016 through the FCC’s Lifeline Program, which gives qualifying low-income households a discount of up to $10 per month.

However, when the COVID-19 pandemic laid bare both the necessity of having quality home internet and the extent of the digital divide, Congress began funding more robust subsidies. The Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021 created the $3.2 billion Emergency Broadband Benefit (EBB) Program through the FCC, which provided monthly subsidies of up to $50 to households making up to 200 percent of the federal poverty line (or $75 to households living on qualifying Tribal lands). At the beginning of 2022, the EBB was replaced by the Affordable Connectivity Program (ACP), a longer-term FCC program that received $14.2 billion from the IIJA, though it only offers subsidies of up to $30 per month. As of April 2022, roughly 11.5 million households have signed up for ACP out of roughly 30 million that are eligible for these programs.

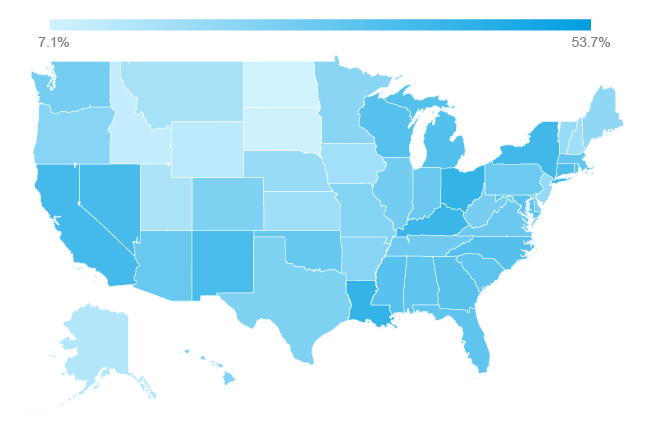

ACP Take Up Rate of Eligible Households by State

SOURCE: ACP Enrollment and Claims Tracker (Universal Service Administrative Company).

Since the onset of the pandemic, several state governments have also started providing subsidies, which have typically been financed at least in part by federal dollars from one of the COVID-19 stimulus packages such as the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act and the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA). Like EBB and ACP, most of these programs target low-income consumers:

- Kansas’s Broadband Partnership Adoption Grant used $10 million in CARES Act funding to help eligible households defray internet subscription costs and even outfit some households with digital devices.

- Vermont’s Temporary Broadband Subsidy Program, also funded through the CARES Act, provides subsidies of up to $40 per month.

- Wisconsin’s Emergency Rental Assistance Program, which is funded by a federal program, now allows households to use payments for internet bills.

- Maryland’s Connect Maryland initiative used $300 million from ARPA and $100 million from the state to fund a variety of programs, including an expanded subsidy that gives households up to a $65 discount on internet service each month for up to 12 months.

- Colorado passed a law in June 2021 directing the state’s broadband office to create a program that uses $5 million to offer subsidies of up to $600 per year for home broadband service to qualifying households.

Some states tied the subsidies to educational initiatives for low-income students:

- Alabama used CARES Act funding for a voucher program that offers 200,000 qualifying low-income students free internet.

- Connecticut invested $43.5 million in its Everybody Learns initiative, which was partially funded by the CARES Act as well as the state’s Emergency Education Relief Fund and the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund. The initiative provides free laptops for 50,000 students, a year of free access to at-home broadband for 60,000 students, and free public hotspots at 200 community sites across the state.

- Delaware used $20 million in CARES Act funding for its Connect Delaware subsidy program that offers free broadband for low-income students.

Massachusetts offers a unique program targeted toward unemployed job seekers called Mass Internet Connect that subsidizes the purchase of Chromebooks and home broadband service (though customers that enrolled after June 1, 2021, receive their subsidies through EBB/ACP).

Incentivizing (or Requiring) ISPs to Focus on Affordability and Adoption

Unlike previous federal broadband funding, the IIJA requires that grant recipients offer a low-cost affordable plan. Similarly, New York passed legislation in April 2021 requiring ISPs to offer a $15 per month broadband plan to low-income New Yorkers. This would be akin to the minimum low-cost packages phone companies were required to offer in exchange for being granted monopoly rights. However, this law is currently being challenged in court.

It is far more common though for states to use incentives rather than requirements to induce ISPs to focus on affordability and adoption. California, for example, offers larger infrastructure grants to ISPs that agree to offer low-income customers a plan costing $15 per month or less.

Many states use a point-based system that prioritizes giving grants to ISPs that offer affordable rates, take steps to encourage adoption, or use other methods to promote digital equity and digital inclusion. Minnesota’s Border to Border Broadband Development Grant uses a 120-point scale to assess applicants on various metrics, including a 10-point category on Broadband Adoption Assistance which awards points based on whether an applicant includes broadband adoption activities in project planning, provides technical support or training on broadband, and offers a low-income broadband assistance program.

Similarly, Missouri’s Broadband Grant Program awards up to 15 points out of 120 for including broadband adoption strategies such as providing technical support and training services, holding digital literacy and online security informational events, and offering an assistance program to low-income consumers. Illinois, Alabama, Indiana, Virginia, Michigan, and California also have similar grant programs that use scoring criteria related to affordability, adoption, digital inclusion, and digital equity.

The gap in adoption rates between adults with a college degree (94 percent) and those with a high school degree or less (59 percent) and the gap between those making over $75,000 per year (92 percent) and those making under $30,000 (57 percent) are both 35 percentage points.

Discounts Through Municipal Broadband and Public-Private Partnerships

At the local level, municipalities that have either municipal broadband or public-private partnerships with privately owned ISPs typically offer a discounted plan for qualifying low-income households. For example, Lincoln, Nebraska, leverages its partnership with Allo Communications to offer qualifying low-income users high-speed internet access for $10 per month through a local government subsidy that is matched by Allo. Nextlight, the municipal broadband network in Longmont, Colorado, offers a no-cost broadband program for low-income families with school-age children. With over 600 communities served by a municipal broadband network of some kind and hundreds more served by a public-private partnership, there are a myriad of other examples of such plans.

Conclusion

Pursuing universal broadband access and closing the digital divide has long been a priority of federal, state, and local governments. While most efforts to expand access have focused on deploying physical infrastructure, governments have traditionally paid far less attention to affordability and other impediments to closing the adoption gap. The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated and exposed the extent of these problems.

Fortunately, in recent years there has been a wave of new initiatives across the country that focus on broadband affordability and adoption, and that trend has only intensified since the onset of the pandemic. However, more can still be done. States and localities should look to their counterparts to see which strategies have been effective, while a slate of recommended policies—such as those from the National Urban League’s (NUL) digital equity and inclusion plan—wait in the wings for governments to implement. With broadband having become an essential utility in the modern era, there has never been a greater need for digital equity and inclusion, to which affordability remains a central impediment. Given the slate of policy options available, governments of all levels can and should rise to the challenge.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Kevin Schwartzbach is a graduate research assistant at the Rockefeller Institute of Government.