Forget Paris?

Yesterday, President Trump withdrew the United States from the Paris Climate Agreement — a joint multination effort to combat climate change. While the Trump administration loudly announced it was going its own way, it was countered with a resounding call for greater cooperation from states, cities, businesses, and other entities to continue under the agreement.

For example, the governors of the states of California, New York, and Washington pledged that their states would remain committed to the Paris Climate Agreement (and would work to get other states to join) and 82 mayors did the same.

The decision to withdraw from the Paris Agreement comes after the Trump administration reversed the federal Clean Power Plant regulations — regulations to lower carbon emissions. After that decision, the Rockefeller Institute wrote that collaborative state models — particularly the Northeast Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) — could fill the void, and the recent announcement by California, New York, and Washington demonstrate a willingness of states to do so.

But as states and cities are moving to work cooperatively to combat climate change, higher education has a unique opportunity to effectuate significant change. It comes down to if there is a willingness to foster more cooperation among the colleges and systems across the nation.

Colleges and universities are some of the largest energy users in the nation — spending nearly $14 billion annually on energy. In many cases, campuses are cities unto themselves. For example, the University of Buffalo’s student body population and employees make it larger than the population of six counties in New York.[1]

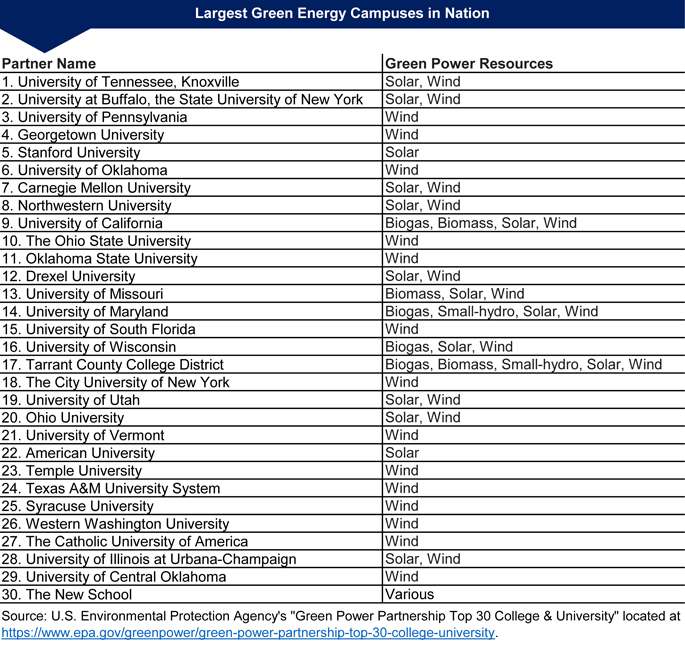

In response, colleges and universities across the nation have focused on becoming more energy efficient, as well as using cleaner sources of energy in order to reduce their carbon footprint. Many have joined coalitions, like the Second Nature network, that include 600 campuses committed to fighting climate change. In New York, Chancellor Zimpher made reducing the SUNY system’s carbon footprint a priority in the Power of SUNY strategic plan. In addition, many schools, both public and private, are taking aggressive steps to become greener. For example, four New York State schools are in the top 30 “Largest Green Power Users” in the nation.

Much is being done at colleges and universities, but they are often accomplished campus-by-campus — or system to system.

But what if higher education harnessed individual campus/system green energy activities and climate goals into mass collective action? It could make a profound difference.

Let me put the potential for scale in perspective. There are more than 24 million students and employees currently at our colleges and universities throughout the nation. If higher education was a state, it would be the third largest state in the nation behind only California and Texas. It would be larger than states like New York and Florida.

There are more than 24 million students and employees currently at our colleges and universities throughout the nation. If higher education was a state, it would be the third largest state in the nation behind only California and Texas.

Since the federal government has retreated, higher education could take a leadership role and follow models like the Northeast Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative. Although colleges and universities aren’t states — and may not be able to do certain things states can do under RGGI, like a cap-and-trade system— they could join together through a formal process to memorialize a more binding unified agreement. In this case, RGGI is a good guide. Through a Memorandum of Understanding, colleges and universities could establish one common program to reduce carbon emissions. Like RGGI, they then could establish an organization made up of faculty, staff, and other experts across the system to provide technical expertise and modeling to implement the program.

As I previously noted, success is limited to participation and big coal and fossil fuel states, like Pennsylvania, have refused to join the RGGI program. But what if SUNY joined with Penn State, UMass, and other large systems under one joint program to lower carbon emissions? As large energy consumers, these systems of higher education could fill the void of state inaction. It could serve as a leadership model in response to federal inaction. And campuses seem inclined to so do. After 86 years of using coal, in 2016, Penn State converted to natural gas, a cleaner source of energy. So the potential is there.

The Rockefeller Institute will begin to explore this and other models in more depth and will provide more detailed analysis of what higher education could do. If higher education worked together with a collective mission, goals, and rules, it could lead the way in combatting global climate change.

Jim Malatras is president of the Rockefeller Institute of Government