There is much confusion about the governmental “division of labor” for cybersecurity in terms of who has responsibility for what preventive and response activities, and how government should engage the many public and private sector partners involved in securing cyberspace. A snapshot of one way in which this problem can be made more tractable and analyzed more systematically came to light recently. A newly public document shows how the U.S. military created a cross-walk of cyber roles and responsibilities across federal agencies — an approach that has potential value for numerous other parts of the broad cybersecurity enterprise.

A recently released Joint Chiefs of Staff doctrinal document on joint “Cyberspace Operations” — JP 3-12 (R)[1] — sheds much light on the preparations, both organizational and programmatic, for U.S. offensive cyber operations in war and conflict. Since such capabilities are not widely discussed, it will likely elicit quite a bit of analysis and dialogue, some of which has already begun.[2] Surprisingly, it also offers some important insights into the division of labor on the defensive side of cybersecurity.

The document reports that “DOD classified and unclassified networks are targeted by myriad actions, from foreign nations to malicious insiders.”[3] It goes further, though, than merely discussing the needs and issues facing the Defense Department. What this piece does, which is valuable, is to succinctly outline and describe the roles of various federal partners in cyberspace.

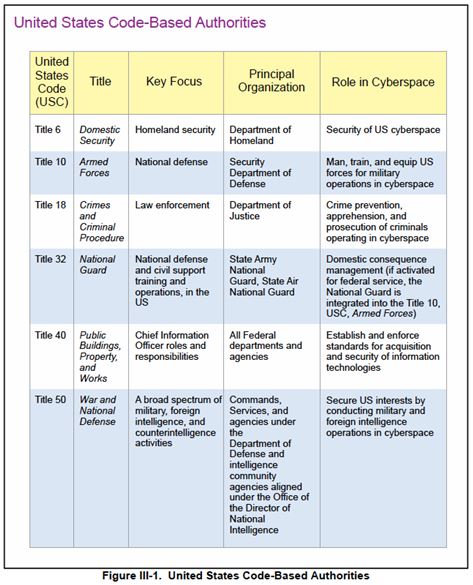

The Cross-Walk of U.S. Code Based Authorities in Cyberspace

A chart on page 36 of this report includes an important table that clearly enumerates the United States Code-Based Authorities of numerous agencies, and their related “roles in cyberspace.” These are mainly federal agencies and federal roles — it does include the National Guard, which can work either as a state-level entity or as a federal one. This graphic — reproduced below — is one of the most parsimonious and effective encapsulations of the federal “division of labor” in the realm of cybersecurity that is publicly available.

http://www.dtic.mil/doctrine/new_pubs/jp3_12R.pdf

In this case, the definition and division of missions like “domestic security,” “national defense,” “law enforcement,” and others is linked directly to the underlying legal justification for agency activity. This kind of cross-walk is incredibly valuable to help understand who has what responsibilities in cyberspace at the federal level. There are several other key documents that outline the responsibilities of federal agencies and partners, most notably the National Cyber Incident Response Plan (NCIRP).[4]

The 2010 interim version of the NCIRP emerged from a Department of Homeland Security (DHS)-led process involving numerous federal agencies with roles in cybersecurity. The NCIRP offers several things that the cross-walk in JP 3-12 (R) does not, including a description of the role of several intermediary organizations — like the Threat Operations Center of the National Security Agency (NSA), which engage in real-time monitoring and coordinate federal responses to emerging cyber incidents. That said, while these are the organizations engaged in responding to particular incidents and threats, they are really just coordinating the various roles of the military, law enforcement, the Department of Homeland Security, and numerous other federal stakeholders that are outlined in the cross-walk in JP 3-12 (R).

In the same way that these various stakeholders share responsibility for countering terrorism threats — with law enforcement responsible for investigations and homeland security responsible for protective measures and risk assessment — so too is the world of cybersecurity a world of shared and sometimes overlapping responsibilities. This cross-walk goes a long way toward delineating and illustrating the division of labor among federal agencies and federal partners. Thus, it offers up the possibility that two more similar cross-walks could be worked out moving forward.

Cross-Walk 1: Federal, State, and Local

The first cross-walk that would be beneficial is to look at the same missions but instead of focusing on the federal government, crossing the layers of federalism to see the division of labor between, for example, federal, state, and local law enforcement. This would be a much more complex cross-walk, and obviously one perhaps less grounded in the federal code, but it would certainly benefit those at the state and local level who are attempting to build the capabilities to respond to such incidents and threats to understand what the division of labor looks like.

Cross-Walk 2: Public, Private, and Not-for-Profit Sectors

The second important crosswalk, and one that could be done either at the federal, state, or even local level, is a comparable look at the division of labor for cybersecurity that did not focus only on the governmental sector but incorporated the private and not-for-profit sectors as well.

Government does not own the vast majority of the computer networks in the United States, and government (at the local, state, or federal level) has virtually no real-time insight into what is happening on these networks. In this sense, unlike most areas of national or homeland security, which are largely the realm of governmental response, industry and the private sector will inevitably have to play a major role in cyber threat response and in developing resilient cyber infrastructure.

Unlike counterterrorism intelligence and information sharing, which are almost entirely governmental functions, the private sector (including security vendors and incident response firms) often has a far better picture of the cybersecurity landscape across industrial sectors, and even across levels of government, than do government agencies that typically can see traffic only on their own networks. There have been attempts to improve information sharing across levels of government, but public sector agencies are unlikely to have the kind of insight that private security vendors do in terms of what is happening on the networks of those companies and industries operating within their jurisdiction.

The unique role that nonprofits play in this area is also necessary to any cross-walk meant to illustrate the division of labor in cybersecurity. Various nonprofits — notably the Information Sharing and Analysis Centers (ISACs) — play an important role in cybersecurity; one that is certainly not apparent in JP 3-12 (R). The ISACs are largely supported by, and composed of, members from private industry. One exception is the Multi-State ISAC, whose members are state and local governments.[5] Other nonprofits, like Federally Funded Research and Development Corporations, play an important role in cybersecurity; for example, the MITRE Corporation’s role in information sharing through the Common Vulnerability and Exposure and Structured Threat Information Expression projects are absolutely imperative to understanding cyber information sharing.[6]

The world of cybersecurity is a complicated patchwork of responsibilities, capabilities, needs, and resources that will likely continue to confuse many of those working to implement solutions and mitigate threats. It is still a world in which the basics of who is responsible for what is not clearly defined or described. JP 3-12 (R) manages to, in a small chart, go a long way toward communicating in fairly simple terms some of the lanes of the road and the division of labor. It is a template that has a lot of applicability for both other levels of government to enshrine their divisions of labor, as well as for cross-sector coordination on cybersecurity, both of which are imperative to improving national cybersecurity.

Dr. Brian Nussbaum is an assistant professor in the Department of Public Administration and Policy at Rockefeller College of Public Affairs & Policy, University at Albany. Dr. Nussbaum formerly served as senior intelligence analyst with the New York State Office of Counter Terrorism (OCT), a part of the New York State Division of Homeland Security and Emergency Services (DHSES).

[1] Joint Chiefs of Staff, Cyberspace Operations. JP 3-12 (R) (Washington, DC: U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, February 5, 2013, http://www.dtic.mil/doctrine/new_pubs/jp3_12R.pdf.

[2] Sean Lyngass, “New cyber doctrine shows more offense, transparency,” FCW, October 24, 2014, http://fcw.com/articles/2014/10/24/cyber-offense.aspx?m=1.

[3] Cyberspace Operations. JP 3-12 (R).

[4] National Cyber Incident Response Plan: Interim Version, September 2010 (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Homeland Security, September 2010),http://www.federalnewsradio.com/pdfs/NCIRP_Interim_Version_September_2010.pdf.

[5] “Member ISACs” (Washington, DC: National Council of ISACs, n.d.), http://www.isaccouncil.org/memberisacs.html.

[6] “Cybersecurity Resources: Standards,” (Bedford, MA, and McLean, VA: MITRE, n.d.),http://www.mitre.org/capabilities/cybersecurity/overview/cybersecurity-resources/standards.