The outlook for higher education: negative.

At least that is according to a new report from Moody’s suggesting that all higher education institutions, including the market-leading elites, are going to be facing significant fiscal pressures in the coming decade. This forecast should not come as a surprise to colleges and universities. Moody’s has had a negative outlook for most of the sector since 2009, but the new report says the situation is even worse than previously believed.

Why? Demographic changes are lowering student demand for higher education — while at the same time a weak economy has exacerbated parents’ and students’ concerns about the cost versus value proposition of a college degree.

The popular media have documented the growing concern among cash-strapped parents and employment-concerned students about tuition and fees. But for a number of years institutions have been able to offset higher costs by increasing their enrollments, because of a continual expansion of the traditional educational pipeline. The number of new high school graduates rocketed up 23 percent nationally between 1995 and 2005.

However, a recent report, Knocking at the College Door, indicates that the number of high school graduates will decline in the coming two decades, particularly in the Northeast, and many colleges and universities are going to struggle to maintain their share of high-school graduates. In fact, those institutions that don’t learn to adapt to the new reality will likely close doors by the end of the decade.

The report, produced by the Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education (WICHE), uses data such as birth rates, immigration, and migration patterns to project the number of high-school graduates in each state. This is largely considered the traditional educational pipeline for new students and where many institutions focus their recruiting efforts. The data suggest that the number of high-school graduates peaked nationally in the 2010-2011 academic year with about 3.4 million graduates. The number is then predicted to decline until 2013-2014, before stabilizing between 3.2 and 3.3 million until 2020-2021. At that point the number of graduates is anticipated to increase, but not returning to the peak experienced two years ago.

The national picture described above is not great, but it masks important regional trends. In the South, the most populous region in the country, the number of high school graduates in 2027-2028 is projected to be 8 percent larger than it was in 2008-2009. This situation is much more dire for the Northeast, which the report defines as Connecticut, Pennsylvania, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, and Vermont. In this region, the number of high-school graduates is expected to decline by 10 percent between 2009 and 2028. This means approximately 65,000 fewer students will be coming through the educational pipeline and moving into higher education, equating to a decline of 77 students per postsecondary institution in the region. (There are 869 postsecondary institutions in the Northeast.) Many higher-education institutions are bound to lose enrollments unless more significant attention is paid to nontraditional students or recruiting students from outside of the region.

In fact, even this regional pictures masks very daunting trends within individual states. With the exception of New York, each state in the Northeast is predicted to have fewer high-school graduates by 2028 than they have today. Maine, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont will be the worst affected, each having declines exceeding 15 percent. (Michigan is the only other state in the nation to fall in this category.) Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania will see declines between 5 and 15 percent. New York is the only state in the region with any sort of notable increase in high-school graduates during the period under study. It will see a decline of about 4 percent between last year (2012) and 2014; and then an increase of about 6 percent by 2022. However, by the end of the projected period, the class of 2028 is expected to be smaller than the class of 2009 and will be a prime target for student recruitment from institutions in neighboring states looking to offset their declines.

But what about revenue streams other than payments from students? The returns generated by endowments remain extremely volatile, according to the latest analysis by the Commonfund Institute and the National Association of College and University Business Officers. Their data suggest that endowments did very well in 2010 and 2011, earning 11.9 percent and 19.2 percent, respectively. However, those returns were bookended by negative returns, suggesting endowments are not stable enough to close big gaps in annual operating budgets.

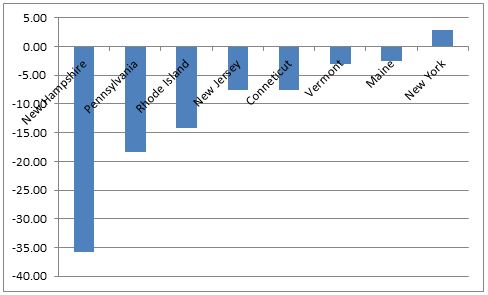

Moreover, investment by state government in higher education is shifting. The annual Grapevine report by Illinois State University and the State Higher Education Executive Officers shows that state support for higher education declined 10.8 percent between FY 2008 and FY 2013 (with decline happening each year). In the Northeast, all states, except New York, saw a decline in their state appropriations ranging from -35.7 percent in New Hampshire to -2.6 percent in Maine (see Table 1).

Table 1. Percentage Change in State Appropriations to Higher Education, FY 2008-2013

Source: Illinois State University and the State Higher Education Executive Officers association

New York saw a small uptick of 2.8 percent in its state appropriation and is indicative of a growing belief that higher education is a critical component of a state’s economic prosperity. Governor Andrew Cuomo has clearly linked funding of higher education to his plan for growing New York’s economy. A significant portion of the new state funding came from the State University of New York’s SUNY 2020 initiative, which targets state investment toward areas of critical need that can support the economic viability of the state (and, notably, is partly premised on the goal of increasing enrollment). This type of funding moves away from the historic block grants that allow colleges and universities to largely decide where to allocate funding toward a model where states are more purposeful in where their investments flow and clearly tying it to an expectation that institutions will contribute to the economic vitality of the state.

Recent announcements by the governors of Connecticut and Massachusetts suggest that other states will be looking at this model as well. In Connecticut, Governor Dan Malloy has proposed that the state would issues $1.5 billion in bonds to invest in the Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) infrastructure at the University of Connecticut’s three campuses. The hope is for the institutions to be able to create new jobs and attract investment from outside of the state. Massachusetts’s Governor Deval Patrick expressed a similar vision, bucking a long tradition of limited funding to public higher education, by budgeting for an 8 percent increase in appropriation to the University of Massachusetts and a 10 percent increase for community colleges.

The prediction of Moody’s may not be quite as bleak if the trend to tie higher education to a state’s economic vitality continues. Institutions may see a small rebound in state appropriations as governors and legislatures recognize that there can be a clear public return on their investment. However, the potential renewed investment by states in the Northeast is not likely to offset the declines in enrollments as a result of fewer high school graduates. And much of the new state funding is not likely to flow to the private colleges and universities, who will feel the brunt of these changing demographics.

Moody’s suggests that this means that many institutions will likely have to downsize, reducing their costs structures. But these trends should also serve as a call for higher education and state government leaders to look for creative solutions. As my co-authors and I suggest in our new book, Academic Leadership and Governance of Higher Education, successful institutions in the future will need to be mission driven, adaptable, and seek out partnerships with the community. When faced with these changing demographics, many institutions will want to respond by expanding programs, often without consideration of their core mission and risking losing their distinctiveness. Successful institutions should instead focus on aligning and strengthening those programs that support the institution’s mission. In competitive markets, institutions need to find way to distinguish themselves from other competitors and staying mission focused is an important first step. When looking to expand the mission, make sure it is strategic and purposeful.

But both states and institutions need to look for ways to adapt to changing demographics and economic conditions. To offset declining local enrollments, institutions will have to look at new populations within the state and reach further into the out-of-state market. In some regions, institutions can target nontraditional students, helping midcareer workers to retool their skills; or expanding access to minority and first-generation college students. When looking out of state, institutions need to look beyond the Northeast. They need to target growth markets in the South and West of the United States (where many Northeasterners have relocated), as well as nations such as China and India that lack the capacity to serve the growing demand for higher education. Institutions in the Northeast might also look at ways to tap into the Canadian market, which is close, but often overlooked.

Finally, institutions should look for ways to partner with each other and other entities to provide low-cost and flexible arrangements to students. For example, Open SUNY is an initiative to allow students to take courses from any number of SUNY campuses in the pursuit of their degree. Regional consortia for public and private institutions could also look at such models. Institutions can also explore partnerships with local business and industry to provide advanced-training programs in high-demand areas.

If the trends continue in their current direction, the closing or consolidation of at least some colleges in the Northeast is a very real possibility. Those that survive will be the ones that learn to adapt to the new conditions.