Last week, President Trump unwound Obama-era climate change programs, including the Clean Power Plant Regulations, the first-ever federal regulations to lower CO2 emissions.[1] After years of strong federal regulatory action, climate change efforts will be left mostly to the states. Given that the carbon emissions emitted in one state don’t necessarily remain confined to that state, regional approaches are important. Regional approaches also help level the playing field so states do not face competitive disadvantages. Even with the void created by the recent federal rollbacks, there are successful regional models states could follow.

In the shadow of weak federal climate rules, how do we get sovereign states to cooperate with one another to take on the issue themselves? The Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) is a collaborative regional program that could serve as a model for states wishing to slow greenhouse gas emissions, such as CO2. RGGI is the nation’s first mandatory regional market-based cap-and-trade program. The program works like this: the states collectively establish a cap on the amount of CO2pollution emitted from power plants in the region. The states issue a limited number of tradable carbon allowances — or paying for pollution — through a regional market. The revenue raised from the process is used to invest in clean energy and clean-energy technology. For example, in New York, power producers buy carbon allowances up to the cap through an auction and some of those proceeds have financed the carbon-free NY-SUN solar installation program, among other programs.

RGGI applies to the electric generation sector,[2] and it was adopted in 2005 by a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) by the governors of seven states: Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, and Vermont.[3] Two years later, Maryland and Massachusetts joined.[4] Under the MOU, the actual cap-and-trade program commenced in 2009.

Under the MOU, each state implemented the program through policy, regulation, and laws (for a list of state-by-state rules, see the Appendix). In addition, a 501(c)(3), called RGGI, Inc., was created to manage the program and provide technical assistance to the states. Although all sovereignty remains with the states, RGGI, Inc. — which is made up of staff from each state — serves an important coordinating function of the program.

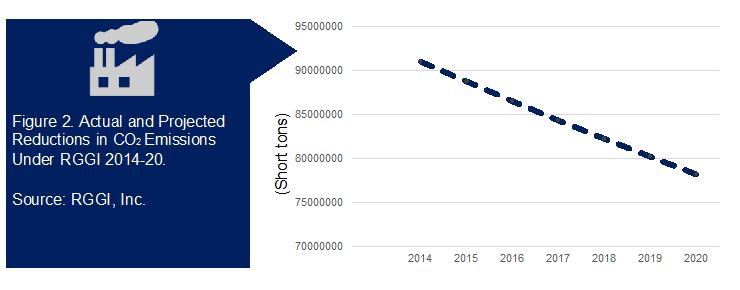

Overall, the program has been successful in achieving its goal to lower CO2 emissions. A recent analysis found that CO2 emissions would have been 24 percent higher in the region if RGGI was not in place.[5] Moreover, about $2 billion in proceeds have been raised for the member states to invest in clean energy technology, energy efficiency, and other climate change fighting initiatives. Like other states, in New York RGGI funds have been a large source of financial support to expand renewable energy, like solar and wind.

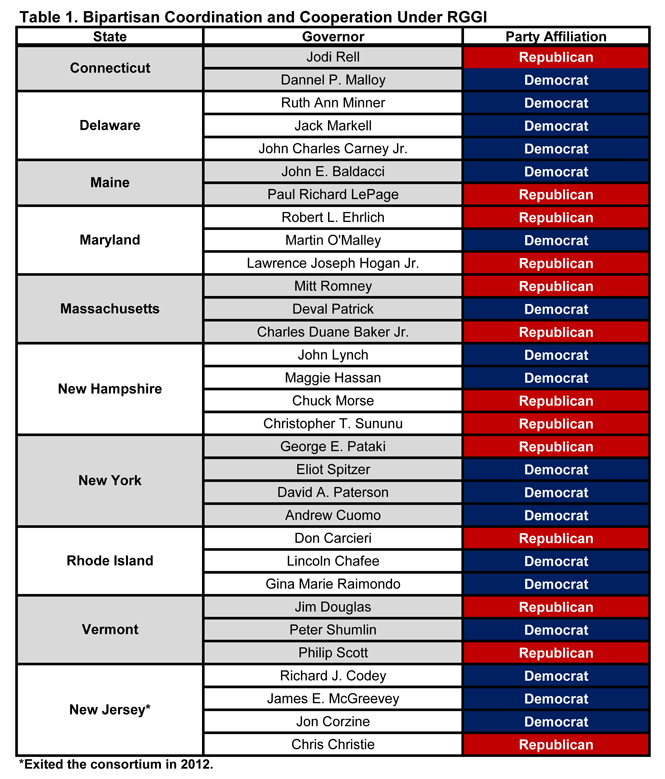

A key to RGGI’s success has been bipartisanship. Even during gubernatorial transitions from one political party to another, membership has been fairly stable (see Table 1). In only one case has a state exited the program when a new party took over. In 2011, New Jersey announced it was leaving the consortium by 2012. The new governor, Chris Christie, called the program “gimmicky” and “a failure.” [6]

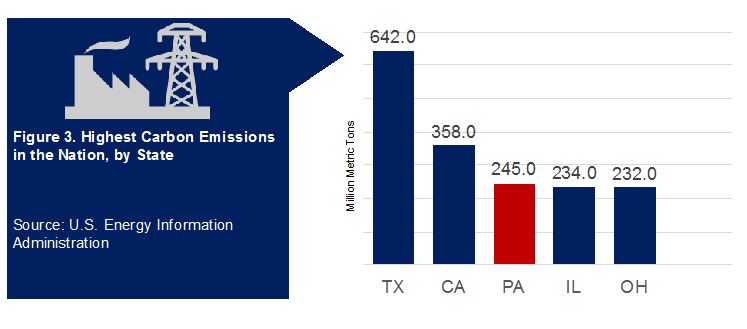

There are limitations to the program. States reliant on carbon-heavy sources of power have been resistant to join the initiative. For instance, Pennsylvania — ranked 3rd highest in the nation in carbon emissions — has refused to join RGGI, even though states to the south, like Maryland, have. When Democrat Tom Wolf was elected governor of Pennsylvania there was talk that the state would finally join the consortium. However, the strong opposition by the coal, oil, and gas industries has thus far kept the state out. More work needs to be done to figure out ways to incentivize carbon-reliant states to join.

Since the creation of RGGI, other states have adopted a cap-and-trade program, namely California[7] (its program has been up and running for two years). Moreover, other regional state consortiums have been formed, like the Western Climate Initiative, but it still is not fully formed.

In the era of federal inaction on climate change, states are left to deal with climate change issue more aggressively. Getting states to cooperate in a collaborative manner will take effort, especially those states that produce the most CO2 emissions, but collaborative models, like RGGI, are a roadmap that states could follow.

Important features of the program include:

-

- Flexible program authority. RGGI was created by MOU and signed by the governors of each state, which has provided more flexibility to easily collaborate, as opposed to each state passing a law to enter the program. Although that has resulted in one state — New Jersey — exiting the program after a new governor from a different political party was elected, overall there has been stability in the membership. However, adopting a program through an MOU may have more flexibility, but perhaps not as much authority to implement a stronger system.

- State sovereignty but centralized management. Although the RGGI program is explicit in underscoring that states are sovereign in the process, creating the 501(c)(3) entity to manage the program has provided a central management structure, which has made the program more stable.

- Nimble program adaptability. The participating states have shown nimble adaptability to address emerging issues, like lowering the CO2 cap when the initial cap was higher than actual carbon emissions.

- Public support. The program is popular with people, making it more difficult for states to exit. A recent poll conducted by Hart Research Associates/Chesapeake Beach Consulting on behalf of the Sierra Club found that 79 percent of people polled support RGGI versus 14 percent who opposed it.[8]

Still, there is room for improvement. Programs like RGGI still:

-

- Need to address how to get heavy polluting states to join. There have been limitations, including the region’s biggest polluter, Pennsylvania, refusing to join. What incentives could be offered to encourage Pennsylvania to join remain elusive. Moreover, how stakeholders can get the state of New Jersey back into the program remains an open question.

- Expanding what the program covers. RGGI is limited to larger electric power generators. How, and if, the program will expand to other sectors remains a work in progress.

Connecticut

- R.C.S.A. 22a-174-31: Control of Carbon Dioxides Emissions/CO2 Budget Trading Program

- R.C.S.A. 22a-174-31a: Greenhouse Gas Emission Offset Projects

- Conn. Gen. Stat. Section 22a-200c: Implementation of Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative. Auctioning of Allowances

Delaware

- 1147: CO2 Budget Trading Program Regulations

- Title 7, Chapter 60, of the Delaware Code, subchapter IIA, §6043

Maine

- DEP Chapter 156: CO2 Budget Trading Program Regulations

- DEP Chapter 158: CO2 Budget Trading Program Auction Provisions

- Title 38, Chapter 3-B: Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative

Maryland

- Subtitle 9: Maryland CO2 Budget Trading Program Rules

- Environment Article, §§1-101, 1-404, 2-103, and 2-1002(g), Annotated Code of Maryland

Massachusetts

- 310 CMR 7.70: CO2 Budget Trading Program Regulations

- 225 CMR 13.00: DOER CO2 Budget Trading Program Auction Regulation

- M.G.L. c. 21A, § 22.

New Hampshire

- Chapter Env-A 4600: Carbon Dioxide (CO2) Budget Trading Program

- Chapter Env-A 4800: Carbon Dioxide (CO2) Allowance Auction Program

- Chapter Revised Statutes Annotated (RSA) 125-O:20-29p, Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative

- Chapter Env-A 4700 Carbon Dioxide (CO2) Offset Projects

- Also see: Chapter RSA 125-O:8, I(c)-(g), Carbon Dioxide (CO2) Allowance Auctions

New York

- DEC Adopted Part 242: CO2 Budget Trading Regulations: Subpart 242-1, 242-2, 242-3, 242-4, 242-5, 242-6, 242-7, 242-8, 242-9, 242-10

- NYSERDA NYCRR Part 507 CO2 Allowance Auction Program Regulations

Rhode Island

- Air Pollution Control no. 46: CO2 Budget Trading Program

- Air Pollution Control no. 47: CO2 Budget Trading Allowance Distribution

- R.I. Gen. Laws §42-17.1-2(19), §23-23 and §23-82 (as amended)

Vermont

- Vermont CO2 Budget Trading Program Regulations

- Vermont Auction Procedures

- Title 30 V.S.A. § 255

[1] For a brief summary see Gavin Bade, “Obama admin. finalizes Clean Power Plan: Deeper CO2 cuts, more time to comply,” Utility Dive, August 3, 2015, http://www.utilitydive.com/news/obama-admin-finalizes-clean-power-plan-deeper-co2-cuts-more-time-to-comp/403323/>.

[2] Applies to approximately 168 power plants in the northeast (or power plants that have the capacity to generate more than 25MW of power).

[3] Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, Memorandum of Understanding (2005) at https://www.rggi.org/docs/mou_final_12_20_05.pdf.

[4] Second Amendment to the Memorandum of Understanding (2007) at https://www.rggi.org/docs/mou_second_amend.pdf.

[5] Brian C. Murray and Peter T. Maniloff, “Why have greenhouse emissions in RGGI states declined? An econometric attribution to economic, energy market, and policy factors” Energy Economics, 51 (September 2015): 581-9.

[6] Christopher Baxter, “Gov. Christie announces N.J. pulling out of regional environmental initiative,” NJ.com, May 26, 2011, http://www.nj.com/politics/index.ssf/2011/05/gov_christie_to_announce_nj_pu.html.

[7] Although RGGI faced industry opposition, lawsuits, and other attacks, it has not nearly been as contentious as California’s program. See Michael Hiltzik, “California’s cap-and-trade program has cut pollution. So why do critics keep calling it a failure?” Los Angeles Times, July 29, 2016, http://www.latimes.com/business/hiltzik/la-fi-hiltzik-captrade-20160728-snap-story.html.

[8] Sierra Club RGGI Survey, July 2016,https://www.sierraclub.org/sites/www.sierraclub.org/files/program/documents/FOR%20RELEASE%20RGGI%20Survey%202016%20Toplines.pdf.