As the novel coronavirus spread across the US, things like work, school, and appointments all shifted online. But tens of millions of Americans are being left out of these basic needs because they don’t have access to high speed internet, or any service at all, in their homes. Many worry the inequities of this digital divide will worsen during the COVID-19 crisis, even as there is hope the spotlight on the problem will lead to a fix after years of waiting.

“This isn’t just a problem of, ‘not everyone can watch Netflix,’” says Tyler Cooper, editor-in-chief of the advocacy group BroadbandNow. “We’re talking about a world that will shift a little bit more into a digital economy after all this is over, and we need to respond and be proactive about that.”

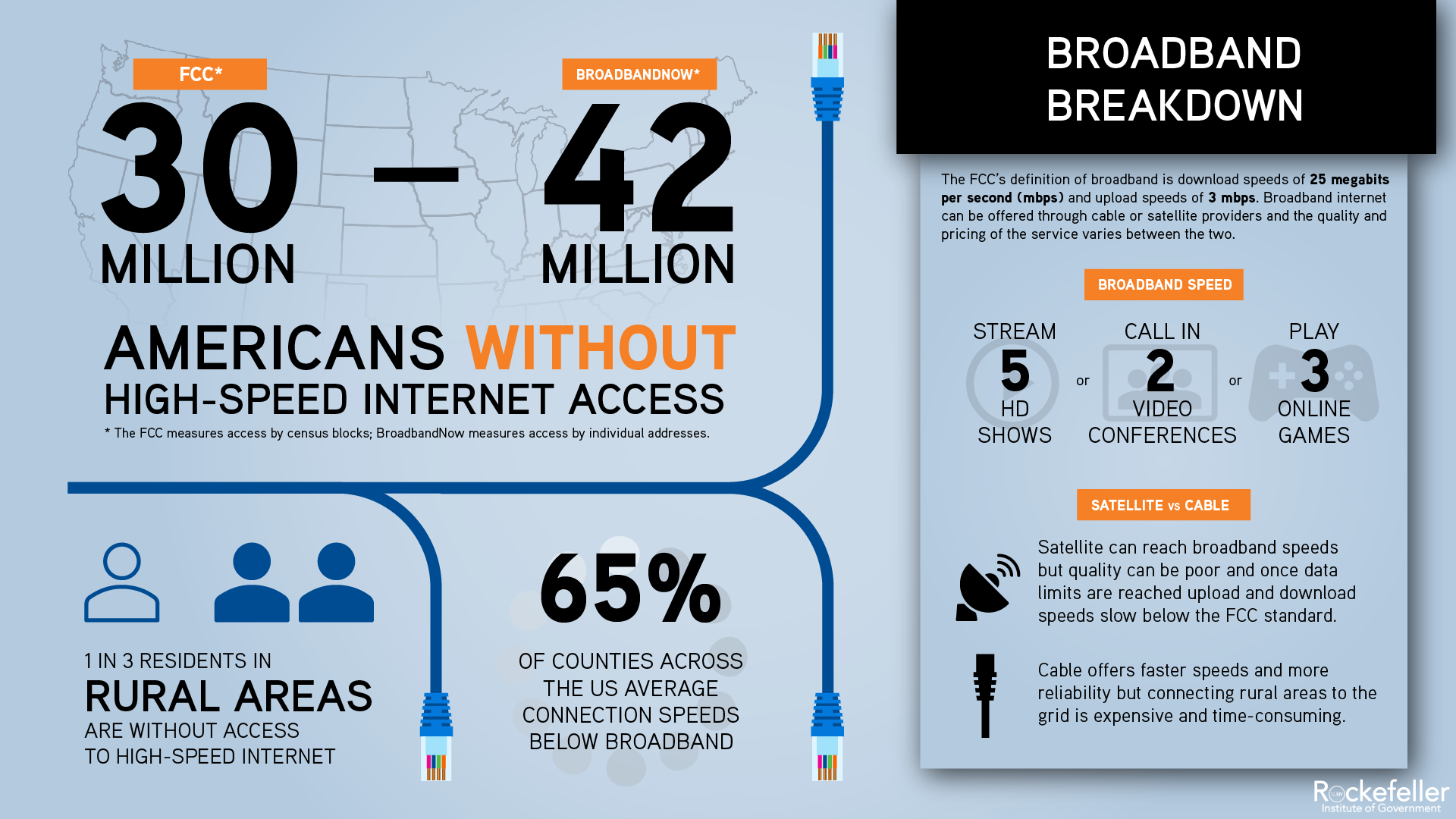

Roughly 30 million Americans (9% of the population) don’t have high speed internet access, or broadband, in their homes according to the Federal Communications Commission. But experts and advocates believe that number is an undercount because of the way it is measured. BroadbandNow, which measures individual addresses instead of census blocks, like the FCC, estimates as many as 42 million Americans don’t have access.

That gap, which widens to one-in-three residents in rural areas, was already a concern for state and local leaders. But now it’s on dramatic display as residents who don’t have high speed internet are being cut off even more from daily life, from doctor’s appointments to online worship services.

“Everybody is recognizing that broadband is a necessity.”

“Some people are now falling through the cracks worse than ever because the United States didn’t do its job in getting everybody connected,” says John Windhausen, executive director of the Schools, Health & Libraries Broadband Coalition, which promotes broadband for anchor institutions and their communities. But, he adds, “I think the mentality has totally changed in the last two months. Everybody is recognizing that broadband is a necessity. We are urging policymakers to solve this problem in the next five years.”

The Basics of Broadband

The FCC’s definition of broadband is download speeds of 25 megabits per second (Mbps) and upload speeds of 3 Mbps. Broadband internet can be offered through cable or satellite providers and the quality and pricing of the service varies between the two. Cable internet providers can offer speeds up to 200 Mbps and data caps at 1 terabits for an average price of $50 per month.

Satellite internet companies are often the only solution available in rural areas. These providers offer speeds “up to” the FCC requirements. The minimum speed is most noticeable when uploading or downloading larger documents, or when streaming video via conference calls or for entertainment. Quality can be poor and service is prone to going out on windy days or during storms. Satellite packages also come with data limits, such as 10 gigabits or 20 gigabits per month. Once the account reaches its data usage cap, upload and download speeds slow to below the FCC standard. And, plans are expensive—ranging from $70 to $150 monthly, depending on the data cap.

National counts of broadband accessibility don’t necessarily consider the realities of connectivity speeds and satellite contracts. It’s no wonder then, that a recent report by the National Association of Counties found that 65% of counties across the US—particularly rural ones—are averaging connection speeds slower than the broadband standard.

The homework gap

With schools closed since mid-March in most states, more than 40 million children are finishing out their school years at home. That’s meant a rapid transition to online learning for students even though as many as 15% of households with school-age children don’t have internet at home, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of census data. During normal times, many of those students head to public libraries or other community spaces when assignments require internet access—but that’s now not an option.

Many districts are trying to compensate by setting up wireless hotspots on buses or at school facilities. But that plan requires access to a vehicle, or that students can get to a wifi school bus when it is available.

“The equity issues in K-12 education have been magnified,” says EAB Vice President of Research, Carla Hickman. “Administrators are trying to strike the right balance between teachers broadcasting on a platform like Zoom versus homework packets they can share with parents and caregivers.”

Minority and low-income students are most likely to be affected by the gap in access, according to Pew. Geographically, lack of access is more widespread in rural areas, but many urban and suburban children who are in homes wired for service still don’t have it because it’s cost prohibitive.

Kathryn de Wit, who heads up Pew’s broadband research, noted that studies have shown that children who don’t have internet access at home tend not to do as well on standardized tests and don’t perform as well on the SATs in times of traditional instruction. “Taking that performance gap further,” she adds, “how does that position them for the future? This is about our overall economic health.”

Access to health-care

The gap in internet service is also being exposed in areas like telemedicine because those who don’t have internet access also tend to have underlying health issues. According to the FCC’s Connect2Health Initiative almost half of the nation’s counties face a “double burden” of having high rates of chronic disease and a need for improved broadband connectivity.

For rural hospitals, whose resources are already scant, poor internet access can impair their ability to treat patients effectively. For example, Illinois Gov. JB Pritzker in his State of the State speech this year recounted the story of a downstate woman who had suffered a stroke. Her local hospital didn’t have the specialists to treat her, but it did have a telestroke robot that instantaneously transferred her tests, CAT scans, and other examinations to specialists at another hospital who made treatment decisions.

“This technology empowers medical professionals to treat patients faster with remote expertise and frankly, that saves lives,” Pritzker said in his speech.

The role of government

When it comes to closing the digital divide, the federal government and states have spent billions expanding access over the last decade and continue to do so. At the beginning of this year, for example, the FCC launched its $20 billion Rural Broadband Opportunity Fund, its largest single investment ever toward closing the digital divide.

More federal funding is emerging in light of the pandemic. The CARES Act passed by Congress at the end of March included a total of $175 million toward federal programs that support expanding broadband and telecommunications. The Emergency Educational Connections Act was recently introduced in Congress and would provide $5.25 billion in supplemental funding for the FCC’s E-Rate program that aids schools in facilitating in-home internet connections for students. And the Healthcare Broadband Expansion During COVID-19 Act calls for an additional $2 billion to fund broadband expansion in hospitals.

The role of states, however, is integral. Not only have states collectively put billions toward broadband themselves, nearly all of them have created broadband offices or designated responsibility for broadband to a state agency, task force, or council. In short, states have better knowledge than the FCC does of where investment is most needed and can work directly with local leaders to facilitate the funding. (Getting a more accurate FCC measure of the broadband gap would also help in directing existing funding to the places that need it most.)

“We know that the digital divide is a problem that won’t be solved by one level of government,” says Pew’s de Wit. “It’ll take coordination at all three levels to get to meaningful solutions.”

But the biggest barrier is the simple fact that bringing high speed broadband internet to rural Americans is expensive and time consuming. For example, one project in North Dakota is receiving $2.8 million to bring service to just 126 households. The public sector has directly funded a few projects with success. The largest is Kentucky Wired, a $1.5 billion project constructing more than 3,000 miles of high-speed, high-capacity fiber optic cable in every county in the state. At the municipal level, Chattanooga, TN, launched its own service in 2010 after dissatisfaction with the private sector offerings. The city-owned service is among the fastest in the nation. And in 2005, the Oregon towns of Monmouth and Independence launched their own internet service that helped the two small towns connect the agriculture industry with the technology and people that can help them become more efficient and productive.

“The internet…isn’t an add-on to your other utilities—it’s a prerequisite for modern living.”

But, getting buy-in for these public investments is difficult and will likely be impossible in the near future, given the deficits that COVID-19 is causing for government budgets. Fitch Ratings analyst Scott Zuchorski thinks it’s more likely the pandemic will result in more public projects that will be paid for by usage rates, similar to how toll roads or other utilities work. “The [broadband usage] data just hasn’t been there for the market to feel comfortable financing these projects,” he says. “But the coronavirus is really highlighting the difference and…as a result, I think there will be a lot more people looking at that.”

Communities and their residents will continue to grapple indefinitely with living and working virtually during the COVID-19 crisis. And there’s every reason to believe that things like education and health-care won’t simply flip a switch and return to normal anytime soon. The hope is that policymakers can use the spotlight now shining on our digital divide to finally erase the inequities it creates.

“The internet is not a luxury anymore,” says BroadbandNow’s Cooper. “This isn’t an add-on to your other utilities—it’s a prerequisite for modern living.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Liz Farmer is a Future of Labor Research Center fellow at the Rockefeller Institute of Government