When you’re riding or driving down a highway, you may notice that there’s often a grassy area running alongside the road. This area is known as the right-of-way (ROW). How ROWs are managed has long been critical to improving road and roadside safety for drivers and passengers. And, while they may not seem like a lot of space, ROWs collectively account for nearly 10 million acres of land in the United States—that’s larger than the states of Maryland, Hawaii, Massachusetts, Vermont, New Hampshire, New Jersey, Connecticut, Delaware, or Rhode Island.

Even if you’ve rarely given them a second thought as you pass them on the highway or thruway, transportation planners and policymakers are beginning to consider roadside ROWs a critical tool for solving big problems—like climate change and the rural broadband gap. Last year, the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) released guidance for states endorsing alternative uses of highway ROWs to create revenue, green jobs, and other benefits. Likewise, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act of 2021 makes explicit connections between such investments in transportation infrastructure and environmental quality.

As part of my ongoing Richard P. Nathan Public Policy fellowship at the Rockefeller Institute of Government, I am investigating potential synergies, conflicts, and tradeoffs in innovative uses of roadside ROWs along state highways. Here, I’m sharing some research in progress and related case studies on three of those potential environmental ROW uses: solar energy arrays, pollinator-friendly plantings, and agricultural crops.

What Are ROWs and Why Do They Matter?

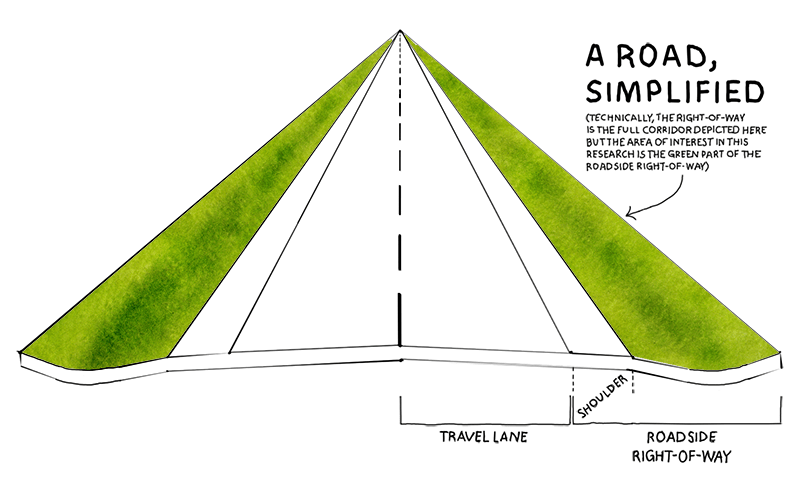

Roadside ROWs are the land on either side of the road, including the shoulder and the vegetation beyond. Sometimes the edge of the property line of the ROW is marked with a fence or visible with a tree line. Who owns the ROW depends on who owns and manages that specific road. Highways are owned and managed by states, so are highway ROWs. Other kinds of ROWs also exist for railroads, canals, and other transportation infrastructure. Utilities also often have associated ROW areas, including transmission lines and gas pipelines.

Highway and other roadside ROWs serve several critical functions. They are designed for road safety, allowing visibility for drivers and the ability to pull off the road, such as being pulled over by law enforcement or to change a flat tire. This provides what’s known as a “clear zone“ or safety zone, an open area next to the highway that allows a driver to regain control of a car that inadvertently leaves the road, reducing collisions. FHWA data indicates that more than half of collisions resulting in a fatality involve a vehicle that leaves the roadway. Roadside ROWs are also designed for drainage, so that water flows away from the highway and doesn’t create standing water that would be a driving hazard.

Facilitating these crucial services requires managing roadside ROW habitats. For example, the clear zone should not have tall vegetation to better ensure driver safety in the case of vehicle breakdowns or collisions and so that animals, such as deer, would be visible to drivers before they entered the road, potentially helping avoid wildlife collisions. Additionally, trees should not be close enough to the road to have overhanging limbs, to avoid branches falling onto the road or shading that could cause icy patches in winter.

There are over 1.2 million miles of roads in the US… with nearly 10 million acres of roadside ROW land.

Some of these roadside design elements are required by federal law (23 CFR Part 625). Additional regulations also exist on a state-by-state basis and are often codified in state-level design manuals published by state departments of transportation. The American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials has an extensive set of guidance for the design choices that go into state highway ROW design. For example, New York State’s Department of Transportation has a Highway Design Manual with a specific chapter on roadside design.

Highway ROWs also include property beyond the required safety zone. The Washington Department of Transportation calls these areas the “selective management zone” and “natural zone” —vegetated areas beyond the clear zone that were historically mowed and aesthetically managed like lawns. These are the areas that states are now considering managing in other ways.

Given how many roads there are in the US, all this land in roadside ROWs adds up. There are over 1.2 million miles of roads in the US, with a corresponding estimate of 4 million hectare—or nearly 10 million acres—of roadside ROW land. Of those, about 600,000 miles are highways and other major roads managed by states. State departments of transportation are in charge of managing several different kinds of roads, including state highways, as well as interstates. In turn, this means that they are responsible for managing enormous amounts of habitat, in addition to roads. County highways and local roads are managed by municipal highway departments. It’s estimated that county road agencies in the US are responsible for almost 300,000 hectares—or over 740,000 acres—of roadside ROW. In sum, there is an enormous amount of roadside ROW land.

Why States May Want to Change How They Manage Their Highway ROWs?

Analyses by the American Society of Civil Engineers have found that there’s a growing gap between transportation infrastructure needs and funding allocated in the US, including an estimated $1.2 trillion gap in surface transportation infrastructure needs by 2029, which includes the roadway system. This is despite the fact that spending by state and federal governments on transportation infrastructure is at near record level highs, according to data from the Congressional Budget Office. This is partly due to funding shortfalls, as well as increased costs for construction and maintenance. The cost of deferred maintenance is also increasing the potential tab, with a recent report estimating that states have $1 trillion dollars in needed infrastructure repairs that have been deferred due to lack of funding. In turn, it means that less funding is available for maintenance, let alone investment in innovative practices.

This has led some states to consider trying to generate cost-savings or revenue from ROW lands, including highway ROWs. For example, Florida commissioned a research report to identify opportunities to offset spending or create revenue for the state using the state highway system. Texas also funded a study examining ways to extract value from the state Department of Transportation’s land holdings, including highway ROWs. They considered the technical, legal, and economic feasibility, as well as potential public perception and impacts, including environmental and safety related impacts.

…financial pressures have led states and municipalities to look for ways to lower the costs of maintaining ROWs or opportunities to generate revenue from them.

This funding gap and the search for new savings and revenue sources is in part due to how transportation agencies and projects are funded in the US. Highway funding from the federal government mostly comes from the Highway Trust Fund. The revenue for the fund comes from excise taxes on gasoline and diesel, known as the “gas tax.” That tax has remained the same rate, 18.4 cents per gallon, for three decades, even though highway building and maintenance costs have not. The CBO recently explored how increasing this tax to account for inflation could contribute to reducing the US federal deficit. Their analyses indicated that revenue from the tax would increase significantly if adjusted. For example, CBO estimates that if the tax increased as little as 15 cents per gallon, the US would raise an additional $100 billion between 2021 and 2025.

Federal funding only accounted for approximately 26 percent of highway infrastructure spending in 2017, with the rest coming from state and local governments. States are raising the rest of the revenue for road construction and maintenance through different tools, including state fuel taxes and tolls. The amount of road spending that comes from state and local revenue varies widely by state. For example, Michigan is estimated to have 82 percent of its road spending generated from state and local revenue, while Alaska generates only 17 percent from the same sources. These financial pressures have led states and municipalities to look for ways to lower the costs of maintaining ROWs with environmentally friendly plantings or opportunities to generate revenue from them through renewable energy generation or agriculture.

Pollinator-Friendly Plantings

States with Pollinator Plantings in ROWs

Image description: A map of all the United States that shows states with pollinator plantings in highway ROWs colored in green. States without are in white. All the states are shaded green except Utah, Wyoming, North Dakota, Wisconsin, and South Carolina.

Almost every state has pollinator-friendly planting initiatives in highway ROWs. Plantings to support pollinators include those explicitly labeled initiatives for pollinators and others framed as wildflower or native plants, beyond the traditional grass seed mixes generally used along highways. Pollinators include any things or beings that transfer pollen between plants, which allows them to produce new fruit, seeds, and plants. Plants can be pollinated by wind, water, or animals—including insects, birds, and bats. Part of the reason pollinator policies have been adopted so widely is because of a growing recognition that pollinators are critical ecologically, agriculturally, and economically. An estimated 150 food crops in the United States, and 80 percent of crops globally, require animal pollination—particularly by insect pollinators. Yet recent research indicates that insect pollinators are declining, in part due to habitat loss and fragmentation.

Planting habitat in highway ROWs may contribute to supporting the insects that these crops, and in turn people, rely on. Research to date indicates that roadsides may be able to provide quality habitat for insect pollinators, although the results are mixed and may depend on the kind of pollinator. Additionally, many scientists, managers, and transportation planners have begun considering highway ROW land as an asset to harness for conservation for threatened and endangered species that pollinate non-crop plants. Nowhere is this clearer than the recent Nationwide Candidate Conservation Agreement on Energy and Transportation Lands. Agreed upon in 2020, this is a voluntary collaboration of state transportation agencies and utility companies, banding together to try to conserve monarch butterflies (Danaus plexippus) using ROWs as habitats. In practice, this means the charge to create and restore habitat for this imperiled insect is being led largely in roadsides.

Almost every state has pollinator-friendly planting initiatives in highway ROWs.

Another reason why state roadside pollinator policies are so prevalent pertains to earlier federal policies and strategies. While it’s not a requirement that every state have pollinator-friendly plantings, the Surface Transportation and Uniform Relocation Assistance Act (STURAA) of 1987 required a portion of roadside ROWs along federal highways to be planted in wildflowers. Additionally, many states adopted state pollinator protection plans soon after the 2015 National Strategy to Promote the Health of Honey Bees and Other Pollinators. My own research examining these policies found that one third of states explicitly included roadside areas in their state pollinator plans as potential pollinator habitat. In more recent years, local governments have also adopted policies promoting or requiring planting native plants, including wildflowers, on public lands.

While pollinators are generally important, wildflower and other pollinator-friendly plantings have many potential benefits for states’ roadsides specifically. Often, plantings are intentionally mowed less frequently to facilitate later blooms to support pollinators, which can reduce costs. They can also improve stability and reduce erosion in the roadside. Some states count plantings towards required or voluntary habitat to support conservation goals, such as those participating in the monarch butterfly Candidate Conservation Agreement with Assurances. There are also potential aesthetic and tourism benefits by creating scenic vistas alongside the road.

The Arkansas Department of Transportation has three related initiatives under its Wildflower Program including Operation Wildflower, which plants new roadside wildflower areas. However, this initiative also highlights a constraint—the potential high cost of these seeds. For example, one of the Operation Wildflower projects along Arkansas’ State Highway 177 several years ago estimated the cost of wildflower seeds at $200/acre. Other states report this as a concern and have tried to find ways to reduce the expense. For example, Illinois commissioned a report on behalf of the Tollway Authority on recommendations for highway roadside pollinator plantings that are ecologically beneficial, while reducing direct costs. The Operation Wildflower program thus relies on external sponsors to cover seed costs for planting new areas. They also advertise their existing maintained wildflower routes, including creating signage and brochures to educate drivers and passengers about the plantings. This is a way to address the sometimes mixed public response to roadside vegetation being mixed flowers versus mown grass.

Solar Energy Arrays

States with Solar Arrays in ROWs

Image description: A map of all the United States that shows states with solar arrays in highway ROWs colored in orange. States without are in white. The states shaded orange are California, Oregon, Colorado, Georgia, Maryland, and Massachusetts.

At least six states across the country have roadside solar policies or practices, including pilots and full-scale projects. Solar arrays in highway roadside ROWs include ground-based arrays, flexible panels, and panels mounted on noise barriers. Additional states have solar energy infrastructure in other related locations, such as on maintenance or rest-area buildings. This reflects a broader growth in renewable energy infrastructure being installed in highway ROWs. The Federal Highway Administration has been tracking and mapping where wind, hydro, and solar power are being installed by states on transportation lands.

There are many potential benefits of solar energy generation in highway ROWs. Transportation agencies may be able to power their vehicles and buildings with the energy, reducing their costs and emissions. The energy generated could also contribute to state renewable energy portfolio standards and goals. For example, New York has a Clean Energy Standard as part of the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act, which includes a goal of generating 70 percent of the state’s electricity from renewable sources by 2030. The energy production benefits are potentially enormous. According to the FHWA, Maryland estimates that once established, their planned 35-site solar arrays on transportation land, including buildings and parking lots, will generate 46,000 megawatt hours per year. That’s 12 percent of the state transportation agency’s annual energy use.

Oregon was the first state in the US to install solar arrays in a highway roadside, with its Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT) Solar Highway Program, which began in 2008. This project produces over 95,000 kwh annually. Oregon has grown their program since, adding a 1.75 megawatt array at a rest area off Interstate 5. The Solar Highway program is a critical piece of Oregon’s renewable energy portfolio standard, which requires 50 percent of electricity in Oregon to come from renewables by 2040. As of 2018, just over 1 percent of Oregon’s electricity is generated by solar energy. There’s a lot more room to grow—the state estimates that there’s the capacity to produce terawatts of solar energy beyond demand.

Oregon’s experience, however, also highlights some of the potential challenges. Some states or localities may have restrictions on renewable energy. In Oregon, the Public Utility Commission does not allow solar panel owners to sell surplus power to the grid, impacting how ODOT could set up its solar highway program. Regulations about “net metering,” which is a mechanism by which solar producers sell excess power to the grid, can incentivize or limit the benefits of solar. This meant that the power produced in the first Oregon solar highway installation was used on site and excess power could not be sold. Tax policies and incentive structures also vary by state. Federal and state tax credits that made the rest area project financially feasible at the cost of $10 million also required establishing a public-private partnership in order to be able to access the tax benefits.

Since Oregon started its program, other states have established roadside solar and more states are planning to follow suit. States planning for solar arrays in highway ROWs now benefit from the work of early adopter states and federal agencies. Given the Solar Highway Program’s technical, financial, and legal challenges, Oregon wrote and released a guidebook for other states considering solar arrays along highways, which includes considerations of state-specific regulatory constraints. The Federal Highway Administration has also released guidance documents for state transportation agencies considering renewable energy in highway ROWs, to ensure federal compliance while planning. Additionally, FHWA has organized peer exchanges, such as bringing state transportation staff to Maryland solar facilities, for states to learn from each other by visiting the sites and discussing challenges and opportunities.

Agricultural Crops

States with Agriculture in ROWs

Image description: A map of all the United States that shows states with agriculture in highway ROWs colored in purple. States without are in white. The states shaded purple are Utah, Nebraska, Kansas, Iowa, Minnesota, Wisconsin, Illinois, Michigan, New York, and North Carolina.

Several states, especially in the northeast and midwest, have programs that allow agricultural crop growing in highway ROWs. This includes living snow fences, which are crops left standing through the winter, and hay or biomass harvesting for energy, as well as one very unique urban farm. These distinctive kinds of agriculture have different considerations and benefits. Haying operations in ROWs may be used for sales or biomass harvesting (growing crops for biofuels) to run agency vehicles, which can save money or raise revenue. Living snow fences can promote increased winter safety for motorists and reduce crashes. Urban ROW farms may contribute to community food security goals.

490 Farmers is an urban community garden and forest in the ROW of Interstate 490 in Rochester, New York. Currently, it’s the only urban farm I’ve identified within a state highway ROW. This is likely due to its unique location relative to the interstate—this particular ROW is physically elevated and separated from the road. However, agriculture—including urban farms—in energy ROWs, such as beneath power lines, are more common than in transportation ROWs and have been around much longer. Existing research on urban farming in energy ROWs can help identify potential challenges and constraints for this practice in roadside ROWs. There are health concerns, as runoff and pollutants from roadways into ROWs may cause food safety issues. There are also infrastructure limitations, as highway ROWs are managed to prevent deadly fixed objects, which includes trees and common farm infrastructure. Yet 490 Farmers’ experience also highlights an opportunity with respect to zoning. Their farm being in a ROW means it is on state land, which appears to have more flexible rules for community gardens compared to the city land surrounding it, while still being close to urban markets and volunteers. Research has shown that urban farms can help increase access to healthy and locally grown food, while adding green space in cities that supports both mental well-being and climate resilience.

Environmental ROWs

Pollinator-friendly plantings include those explicitly labeled initiatives for pollinators and others framed as wildflower or native plants, beyond the traditional grass seed mixes generally used along highways.

Solar arrays in highway roadside ROWs include ground-based arrays, flexible panels, and panels mounted on noise barriers.

Agriculture in ROWS include living snow fences, which are crops left standing through the winter, and hay or biomass harvesting for energy, as well as one very unique urban farm.

Conclusions

While these three case studies highlight that there are many exciting possibilities for highway ROW uses, they also point to constraints and tradeoffs. These potential roadside ROW areas are all most cost effective to install and maintain in areas that are flat, that have good sun exposure, and that have soft soil (i.e., not a rocky outcrop). Additionally, these roadside management options may not be compatible with each other. For example, some aquatic insects have been found to mistake solar panels for water. This may indicate that alternative energy development like solar in roadsides is mutually exclusive of using roadside ROWs for pollinator conservation. However, there are also possible synergies. A recent feasibility study conducted for Minnesota focused on strategic co-location of renewable energy and communication infrastructure in the state’s highway ROWs.

This raises the question of how states can make decisions across their roadside ROW landholdings, and of which use is best for a given area, rather than evaluating individual projects or potential uses one by one. Many of these states are already using a broader transportation planning framework known as context sensitive design, which is an approach that considers where and when different kinds of uses might be appropriate, who the stakeholders might be, and what policy goals they want out of these spaces. This can be applied to highway ROWs. For example, back in 2013, researchers in Michigan developed a Roadside Suitability Index assessment for the state department of transportation for roadside ROWs using context sensitive design. The goal was to identify areas in Michigan that might be best suited for one of these innovative uses, for example, renewable energy. Their approach involved mapping the whole state using 21 different datasets. After this assessment, the uses that they decided were most important were based on the vegetation and land use in the surrounding landscape, such as the amount of agriculture and residential land.

Yet these potential impacts assume the economic and policy status quo. As the State Smart Transportation Initiative noted in its 2015 report, many potential strategies for states and transportation agencies to increase existing revenue sources or create new ones will require state-level legislation, not just planning. For example, Wisconsin amended its state laws to alter where and how the state can construct electricity infrastructure to prioritize existing highway corridors. This reveals how critical policy tools are for harnessing roadsides as assets. As I continue my Richard P. Nathan Public Policy fellowship at the Rockefeller Institute of Government, I will be examining how roadside managers, planners, and state policymakers are making decisions, especially when alternative ROW uses are in conflict or when regulatory barriers exist. Examining current state laws and policies, such as those about renewable energy or how state transportation agencies are permitted to raise funds, as well as solutions piloted by other states, can help states more holistically plan and create opportunities for innovative roadside ROWs into the future.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Kaitlin Stack Whitney is a Richard P. Nathan fellow at the Rockefeller Institute of Government and is an assistant professor in the Science, Technology & Society Department at the Rochester Institute of Technology.