The term “mass shooting” understandably evokes visceral reactions from policymakers and the public alike, particularly when accompanied by heartbreaking images of impacted people and scenes. At the same time, however, this term is also typically accompanied by confusion regarding exactly what kind of event is being described. This is because, at present, there is no uniformly accepted definition of “mass shooting,” and depending on the agency or organization using it, the term can mean something different. This variety of definitions not only results in confusion but also has important implications for understanding these kinds of events, as well as for preventing them from occurring.

Take, for example, the Gun Violence Archive (GVA), which is one of the most regularly referenced publicly available data sources. The GVA defines “mass shootings” based solely on a numerical threshold of four or more individuals shot or killed, excluding the perpetrator. It does not consider the context surrounding the shooting, such as whether it was premeditated versus spontaneous, occurred in private (i.e., a residence) or public, or was associated with a felony or gang-related activity.

Other sources, such as the USA TODAY/AP/Northeastern University mass killing database and The Violence Project, draw from the earlier definition proposed by the Congressional Research Service (CRS), which defined a mass shooting as an incident in which four or more people are killed with a firearm in a single event. This was based on the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s (FBI) definition of mass murder and narrowed to address only those incidents perpetrated with firearms. Notably, the CRS also differentiates between mass shootings broadly and those that occur in public spaces such as workplaces, schools, and places of worship, as opposed to in someone’s home, accounting for contextual differences between shootings that occur in public and private spaces.

Following the 2012 mass shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut, Congress codified the definition of “mass killing” to capture incidents in which three or more people were murdered in a single incident in a public location, though these events did not necessarily have to be perpetrated using a firearm. In 2022, Congress expanded the application of the three-fatality threshold to “mass shootings,” which captured those events perpetrated using firearms that met the same criteria (i.e., multiple deaths, public location(s), single incident). This definition was then adopted by Mother Jones in amending their own mass shootings database, which had previously used the four-fatality threshold prior to Congress’s issuance of the new mass killing definition in 2013.

Still, other resources utilize a broader definition of “mass shooting” to overcome some of the perceived challenges, as discussed more in-depth in the next section, of these other categorizations. At the Regional Gun Violence Research Consortium (RGVRC), we specifically focus on mass public shootings in our relevant analyses, which we define as:

[A]n incident of targeted violence carried out by one or more shooters at one or more public or populated locations. Multiple victims (both injuries and fatalities) are associated with the attack, and both the victims and location(s) are chosen either at random or for their symbolic value. The event occurs within a single 24-hour period, though most attacks typically last only a few minutes. The motivation of the shooting must not correlate with gang violence or targeted militant or terroristic activity.

A final term often interwoven into this conversation is “active shooter incident” (or event), which was introduced by the FBI in 2014. This term originally was used by law enforcement to describe incidents in progress where an individual is killing or attempting to kill others, but it was later adopted by the media more broadly and used synonymously with “mass shooting” to describe events similar to Sandy Hook. The term “active shooter event” helps to capture incidents that result in limited or no fatalities or injuries that share the hallmarks of a mass shooting but do not go on to become one under certain definitions. Although some active shooter incidents will evolve into “mass shootings” (based on either three or four fatalities or casualties1), not all will—some events will thankfully end before any casualties occur.

Taken together, these similar-sounding but disparate terms—alongside their varied definitional parameters—have been used interchangeably as though they all mean the same thing. As a result, considerable confusion exists surrounding the “mass shooting” phenomenon that warrants clarification to better guide policy as well as prevention and response efforts. This blog examines the different challenges stemming from this definitional debate surrounding “mass shootings” and offers considerations for how to continue to move this conversation forward.

TABLE 1. Characteristics of Definitions by Source

| Source | Term | Victim Threshold | Includes Injuries |

| Congress | Mass Killing | 3+ | No |

| Mass Shooting | 3+ | No | |

| Gun Violence Archive | Mass Shooting | 4+ | Yes |

| USA TODAY/AP/ Northeastern | Mass Killing | 4+ | No |

| Mass Shooting | 4+ | No | |

| The Violence Project | Mass Shooting | 4+ | No |

| Mother Jones | Mass Shooting | 3+ | No |

| RGVRC | Mass Public Shooting | Multiple | Yes |

| Federal Bureau of Investigation | Active Shooter | None | N/A |

NOTE: Victim threshold refers to the minimum number of victims necessary for a case to be included in the respective data source. The “includes injuries” category references whether the victim threshold includes injuries to meet said minimum (yes) or if it is fatalities only (no).

Challenges of the Definitional Differences

When the term “mass shooting,” along with the phrase “school shooting” (originally used to describe incidents of mass gun violence that occurred in educational institutions), first appeared consistently in the public discourse, it was used to describe a specific subset of firearm violence—premeditated, predatory shootings that had widespread impacts in the locations and broader communities in which they occurred.

The most well-known example at the time was—and largely remains—the 1999 shooting at Columbine High School in Jefferson County, Colorado, in which two teenage gunmen carried out an attack that left 13 dead,2 21 others injured by gunfire, and a nation in shock. The subsequent investigation into the shooting revealed that the perpetrators had planned the attack for nearly two years prior. Consequently, the use of the term “mass shooting” in a post-Columbine era typically was used to categorize incidents that were similar to the attack—extensively planned yet seemingly random in nature.

Over time, however, the phrase “mass shooting” began to be more loosely applied to any multi-victim incident of gun violence. As a result, incidents that bore little contextual resemblance to Columbine beyond multiple victims (either injured or killed, depending on the source) were being treated synonymously with this archetypal case. Examples include shootings that occur outside of bars and nightclubs, resulting from the escalation of a physical or verbal altercation in which a firearm is present and used for self-defense or retaliation, as well as those that occur in private residences and take the form of a family annihilation or murder-suicide.

Although these different types of shootings are each tragic and prevention of similar incidents in the future should be a priority, their qualitative and contextual differences are important to consider in order to identify the respective policies and practices necessary to achieve such an end. The extensive planning period that precedes events like Columbine, for instance, can provide a much different window for intervention and ultimately prevention than a more spontaneous shooting that erupts from the escalation of a fight. Similarly, there may be different interventions that would be useful in cases where the victims are known to the would-be perpetrator, as in the instances of more private mass shootings, compared to those where the victims are randomly shot.

A second and similar challenge is understanding what does or should constitute a “mass shooting” based on the differences in numerical thresholds within these definitions. A limitation of the four-fatality threshold is that there are numerous reasons why individuals who are shot do not die, including—but not limited to—what type of firearm and ammunition they are shot with, where on their person they are hit, how quickly medical assistance can be rendered, and the distance to a trauma center. These factors, however, do not negate that the perpetrators in these cases also likely intended for these individuals to die. Consequently, the question remains as to why many sources have set the threshold to four rather than three or even two casualties—that is, how is the “mass” in mass shooting defined?

Requiring that four or more people have to die to be considered a mass shooting also can serve to deny an impacted community their experience. For example, the 1998 shooting at Thurston High School in Springfield, Oregon, claimed the lives of two students but left 25 others injured. More recently, the 2019 shooting at STEM School in Highlands Ranch, Colorado, left one student dead and eight others injured. By requiring that four or more people have to die to be considered a “mass shooting,” these two incidents—in which there were 27 and nine total casualties respectively (not counting the numerous others who experienced psychological and emotional trauma from the incidents)—would not be counted in data sources using that threshold. This is despite remarkable similarities related to offender and incident characteristics of other shootings with higher fatality counts (e.g., Columbine or the 2018 mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida).

A third challenge stemming from these definitional differences is understanding exactly how often mass shootings are occurring in the United States. The amount of attention devoted by the media to mass shootings, especially those that are similar to Columbine, has made these deeply concerning but less common types of gun violence incidents appear almost epidemic-like. Moreover, depending on the source cited (see, for example, Table 2), the number of mass shootings can range from just a few incidents per year to more than 600 annually.

TABLE 2. Descriptive Statistics of Mass Shootings by Data Source, 2023

| Database | Number of Incidents | Average Fatalities | Average Injuries |

| Gun Violence Archive | 659 | 1.1 | 4.1 |

| USA TODAY/AP/ Northeastern* | 39 | 5.2 | 2.4 |

| The Violence Project | 8 | 8.0 | 5.6 |

| Mother Jones | 12 | 6.3 | 5.4 |

| RGVRC | 16 | 5.3 | 4.4 |

NOTE: Data from USA TODAY/AP/Northeastern were culled to include only the incidents perpetrated with firearms.

Moving Beyond the Definitional Challenges

Importantly, what often escapes the discourse about mass shootings is that these tragic events are among the rarest forms of gun violence, accounting for less than one-half of a percent (0.3 percent) of all firearm-related fatalities annually. Yet by focusing a disproportionate amount of attention and resources on the rarest form of gun violence, it shifts the priority away from addressing more frequently occurring types, including firearm suicides and community-based gun violence. Efforts still must be made to address the occurrence of mass shootings, but any such approaches must be grounded in the actual (rather than mediated) context of the phenomenon, which begins with a more concrete understanding of what we are trying to prevent or respond to.

Given the varied definitions currently employed when discussing mass shootings, as well as the corresponding datasets that accompany them, it is unlikely that consensus about how to define and operationalize this phenomenon will be reached anytime soon. In light of the large public interest in “mass shootings,” having a resource based on a broader definition, such as the GVA, may be helpful in cataloguing all instances of multiple-victim shootings. Yet, to inform policy and practice related to prevention and response moving forward, it is vital to consider and even prioritize the specific contexts surrounding different types of mass shooting events in guiding such efforts.

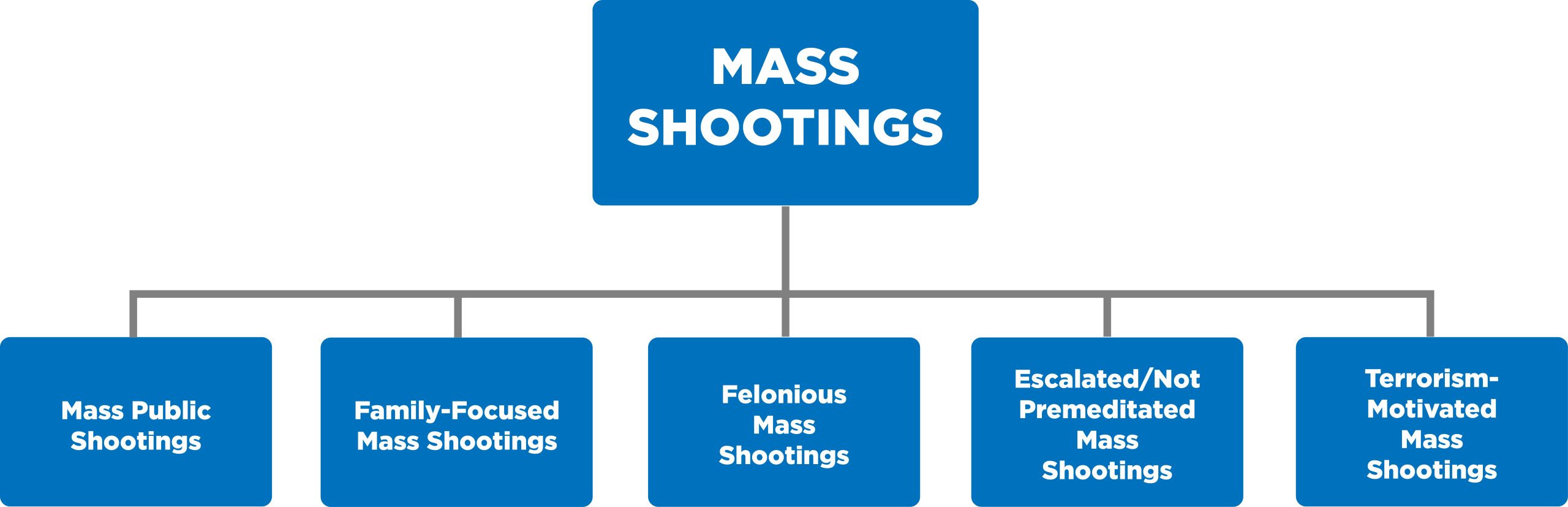

FIGURE 1: A Proposed Organizational Model for Analyzing Mass Shooting Incidents

NOTE: This model would capture and include active shooter incidents with three or more total casualties (fatalities and/or injuries).

We therefore propose a new organizational mechanism that can both encompass the broader range of types of shooting events that occur and reflect the more specific contexts of those events based on their differences. As depicted in Figure 1, rather than blanketly applying “mass shooting” to a set of incidents, this term can instead be used as an umbrella to capture all incidents of multiple-victim firearm violence (e.g., as evidenced by the GVA definition and data). From there, events can be organized and grouped based on their varying contexts for analysis of similar incidents and identification of opportunities for intervention based on their more specific circumstances. For instance, extreme risk protection orders may be more successful at helping to prevent mass public shootings and those incidents that are family-focused, but could have less utility for reducing those events that are not premeditated. Universal background checks, similarly, may be less helpful in preventing felonious mass shootings (i.e., those events that occur in conjunction with another felony) compared to other categories.

As we continue to move this conversation forward, it is critical to be clear about the problem we are seeking to address. Doing so will provide a fuller picture of the state of mass shootings in the United States while also allowing for more nuanced and robust conversations about how best to prevent these tragedies from occurring.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Jaclyn Schildkraut is the executive director of the Regional Gun Violence Research Consortium (RGVRC) at the Rockefeller Institute of Government.

H. Jaymi Elsass is an associate professor of instruction in the School of Criminal Justice and Criminology at Texas State University.

Emily Greene-Colozzi is an assistant professor in the School of Criminology and Justice Studies at the University of Massachusetts Lowell.

Brent Klein is an assistant professor in the Department of Criminology & Criminal Justice at the University of South Carolina.

All are scholars within the RGVRC.

The authors wish to thank RGVRC member Hunter Martaindale for his feedback on an earlier draft of this blog.

[1] In this context, the term “casualties” represents the total number of fatalities plus injuries.

[2] In March 2025, the number of fatalities was revised to 14 as one of the students wounded in the shooting, Anne Marie Hochhalter, passed away the month prior from complications stemming from her injuries. Her death subsequently was ruled a homicide.