In recent years, the United States has witnessed significant shifts in attitudes and policies regarding cannabis. With increasing acceptance of its medicinal and recreational use, more than half the states have enacted laws to legalize cannabis, reflecting a broader trend towards decriminalization and regulation. Despite recent movement toward reclassifying marijuana’s status on the Controlled Substance Act (or, rescheduling), cannabis is still a Schedule I drug and is considered illegal by the federal government. This tension between the federal government and states’ cannabis policies manifests itself in myriad ways, including restrictions on cannabis users owning a firearm.

Section 922 (g)(3) of the 1968 Gun Control Act (18 U.S.C. §922 (g)(3)) makes it illegal “for any person who is an unlawful user of or addicted to any controlled substance (as defined in section 102 of the Controlled Substances Act (21 U.S.C. 802))” to possess a firearm. The US Department of Justice’s Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives’ (ATF) standard firearm transaction form requires that before the legal purchase of any firearm the applicant affirms that they are not a cannabis user, even in states where cannabis (medical or adult-use) has been legalized. This is a disqualifying statement that would lead to a rejection of the application and the inability to purchase a firearm.

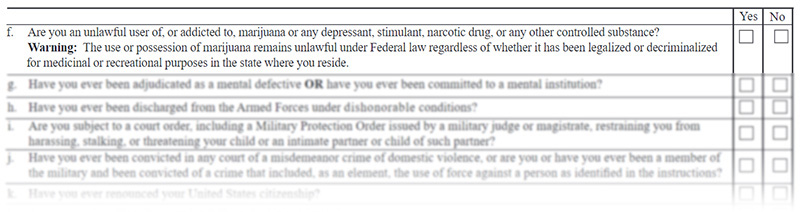

Question 21f on the ATF firearm transaction form.

New legal jurisprudence related to restrictions on firearms, however, has resulted in a changing landscape that could impact the interpretation and application of 18 U.S.C. §922 (g)(3). More specifically, this shift follows the 2022 US Supreme Court decision in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association, Inc. v. Bruen (hereafter Bruen), a challenge to New York State’s requirements for an unrestricted license to carry a concealed firearm in public places, which set a new standard for how the constitutionality of firearm restrictions would be measured:

[w]hen the Second Amendment’s plain text covers an individual’s conduct, the Constitution presumptively protects that conduct. The government must then justify its regulation by demonstrating that it is consistent with the Nation’s historical tradition of firearm regulation. Only then may a court conclude that the individual’s conduct falls outside the Second Amendment’s “unqualified command.”

This effectively replaced the standard that the Court previously established in District of Columbia v. Heller (2008)—whether the state’s reason for enacting the firearm restriction outweighs the burden of said restriction—with the more stringent criteria that the state must be able to demonstrate that the firearm regulation proposed is rooted in similar historic regulations. Since Bruen, several recent court cases have relied upon its new framework to argue that 18 U.S.C.§922 (g)(3)’s prohibition on gun ownership by marijuana users is no longer permissible.

United States vs. Patrick Darnell Daniels. Jr.

In April 2022, Patrick Darnell Daniels, Jr., was pulled over for driving without a license plate. One of the officers noticed the smell of cannabis when approaching the vehicle. A search of the vehicle found cannabis butts in the ashtray and two loaded firearms. A drug test was not completed, but after receiving his Miranda rights, Daniels admitted to being a regular consumer of cannabis. Based on that admission, Daniels was charged with a violation of 18 U.S.C. §922 (g)(3).

The Supreme Court’s ruling on the Bruen case was handed down while Daniels was under indictment and his counsel moved to dismiss the case under the new criteria outlined by the Supreme Court, arguing that 18 U.S.C. §922 (g)(3) was unconstitutional. The district court denied the motion, finding that 18 U.S.C. §922 (g)(3) was a longstanding gun regulation that was comparable to laws that disarm those with felony convictions and those with mental illnesses and that it met the “historical tradition of firearm regulation” required by Bruen. A jury found Daniels guilty; he was sentenced almost four years in prison, three years of supervised release, and was barred for life from possessing a firearm. Daniels and his legal team appealed the decision to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals.

The Fifth Circuit Court, however, was less persuaded that the historical evidence presented by the government was sufficient or analogous enough to satisfy Bruen. In their opinion, the Fifth Circuit differentiated between prohibitions against using firearms while currently under the influence and a prohibition against possession of a firearm by an individual who has a history of drug or alcohol use. Although they found a historical tradition of restrictions on the former, they did not for the latter:

In short, our history and tradition may support some limits on an intoxicated person’s right to carry a weapon, but it does not justify disarming a sober citizen based exclusively on his past drug use. Nor do more generalized traditions of disarming dangerous persons support this restriction on nonviolent drug users.

The Fifth Circuit Court therefore reversed Daniels’ conviction, finding it “inconsistent with our ‘history and tradition’ of gun regulation” and a violation of the Second Amendment. Their ruling did not invalidate 18 U.S.C. §922 (g)(3) in all applications, limiting their ruling only as applied to Daniels’ case.

The case has been appealed to the Supreme Court, but the US Solicitor General has requested that the petition for a writ of certiorari, or a decision by the Court as to whether to take the case, should be held until a Supreme Court decision is made later this year in another case, United States v Rahimi. The argument brought forward in Rahimi, a challenge to a federal prohibition of firearms by people subject to a domestic violence restraining order (18 U.S.C. § 922(g)(8)), also relies on the standard set by Bruen and there is significant overlap in the government’s arguments in Rahimi and Daniels; depending on how the Court rules in Rahimi, it could limit or alter how Bruen is applied going forward. One of the main arguments in Rahimi is that there is not a tradition of prohibiting firearms from those accused of domestic abuse. The Rahimi case is the first to reach the Supreme Court relying on the precedent set in Bruen, so the Rahimi ruling may offer additional guidance on how the ‘history and tradition’ standard should be applied or could otherwise narrow the applicability of Bruen.

United States vs. Jared Michael Harrison

Jared Michael Harrison was pulled over in May 2022 for failing to stop at a red light. Similar to the circumstances in US v Daniels, law enforcement smelled cannabis in the car and a search of the vehicle uncovered a loaded revolver and a backpack containing cannabis, gummies, and vapes. No drug test was administered. Harrison was indicted by a federal grand jury on a violation of 18 U.S.C. §922 (g)(3). Following Bruen, he challenged the indictment, arguing that 18 U.S.C. §922 (g)(3) was an unconstitutional infringement of his Second Amendment rights based on the claim that there is no history or tradition of similar firearm regulations.

The federal government’s argument in this case was two-fold. First, that Harrison is not protected by the Second Amendment as he is not a “law-abiding citizen,” given his use of a federally illegal substance. And second, that there is a history of preventing “presumptively risky” people from possessing firearms, which they argued would extend to cannabis users.

The US District Court for the Western District of Oklahoma was, however, unconvinced by the case presented by the government, relying on the precedent set by Bruen. Like the decision by the Fifth Circuit in Daniels, the District Court emphasized that, historically, firearm prohibitions presented by the government were restricted on the use of a firearm by an intoxicated person, rather than a restriction on possession of a firearm by someone who had ever previously used an intoxicant. These historical prohibitions referenced by the federal government were also much narrower in that they applied to public places; unlike the prohibition in 18 U.S.C. §922 (g)(3), none of the laws referenced were “a total prohibition on possessing any firearm, in any place, for any use, in any circumstance—regardless of whether the person is actually intoxicated or under the influence of a controlled substance.”

The District Court ruling has since been appealed to the Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit, but as in Daniels, is on hold until the Supreme Court’s ruling in Rahimi.

… the Rahimi ruling may offer additional guidance on how the ‘history and tradition’ standard should be applied or could otherwise narrow the applicability of Bruen.

United States vs. Paola Connelly

In December 2021, law enforcement in El Paso responded to an emergency call by the neighbor of Paola Connelly, regarding an incident with Connelly’s husband. A search of the home uncovered several firearms registered to Connelly, as well as cannabis, cannabis extract, and a homemade cannabis greenhouse. Connelly informed investigators that she uses cannabis regularly as a sleep aid and to help with anxiety. She was indicted for possession of a firearm in violation of 18 U.S.C. §922 (g)(3). Connelly’s movement for dismissal of her indictment was denied by the District Court for the Western District of Texas; however, in light of the Fifth Circuit’s ruling in Rahimi, Connelly, in February 2023, submitted a motion for reconsideration (a re-examining of a ruling after a change in law or error).

The government presented similar arguments to those in Daniels and Harrison: that the Second Amendment only protects “law-abiding, responsible citizens” and that laws passed during the colonial era and Reconstruction regulating firearms demonstrate a longstanding tradition of restrictions on intoxicated individuals.

The District Court for the Western District of Texas echoed the decisions made by US District Court for the Western District of Oklahoma in Harrison and the Fifth Circuit in Daniels and did not find the government’s case persuasive. They dismissed the eight cases cited by the government as failing to be analogous to 18 U.S.C. §922 (g)(3), finding that the historic laws regulated firearms differently and for different reasons. “To summarize, the historical intoxication laws cited by the Government generally addressed specific societal problems with narrow restrictions on gun use, while § 922(g)(3) addresses widespread criminal issues with a broad restriction on gun possession.” The court was also unpersuaded that Connelly’s consumption of cannabis fails to meet the historic interpretation of who would be considered “law-abiding”; Connelly had not been convicted of or even charged with a drug crime and, even if she was, under federal law her possession would be a simple misdemeanor charge.

In short, the historical tradition of disarming “unlawful” individuals appears to mainly involve disarming those convicted of serious crimes after they have been afforded criminal process. Section 922(g)(3), in contrast, disarms those who engage in criminal conduct that would give rise to misdemeanor charges, without affording them the procedural protections enshrined in our criminal justice system.

The District Court for the Western District of Texas granted Connelly’s motion to reconsider and dismissed the case against her. The Department of Justice appealed, and the case is currently pending in the Fifth Circuit.

Greene vs. Garland

In another case filed in January 2024 in the District Court for the Western District of Pennsylvania, Robert Greene, a medical marijuana user and former District Attorney in Pennsylvania who wants to possess a firearm, is challenging 18 U.S.C. §922 (g)(3). His challenge argues it is a violation of the standards set in Bruen, citing that there is “no historical tradition of categorically banning individuals from keeping and bearing arms due to their use of a medicinal substance.” Oral arguments have not yet been scheduled for this case; the most recent filing in April 2024 has requested a preliminary injunction that would prohibit the federal government from enforcing 18 U.S.C. §922 (g)(3) until this case is resolved.

At least until [the decision in Rahimi], many Americans will have to choose between gun ownership and cannabis consumption.

State Action

The courts are not the only arena in which challenges to cannabis users’ prohibition of gun possession are playing out. Several states have legislation introduced or ballot initiatives pending that address restrictions on gun ownership by cannabis consumers. In Colorado, organizers are hoping to be able to place an initiative on the November 2024 ballot that would eliminate a state restriction that prohibits law enforcement from granting concealed carry permits to cannabis users. If passed, the ballot would not affect federal 18 U.S.C. §922 (g)(3). The measure has been approved for circulation and signature collection. A proposed 2024 ballot measure in Arizona would allow medical marijuana card holders to legally obtain and own firearms. In Maryland, a bill is moving thought the legislature that would amend state law to ensure that “a person may not be denied the right to purchase, own, possess, or carry a firearm solely on the basis that the person is authorized to use medical cannabis.” A bill introduced in Pennsylvania would update the state’s Uniform Firearms Act to ensure that a valid medical marijuana cardholder is not considered an unlawful marijuana user. It is interesting to note that in both Arizona and Maryland, states that have legalized both medical and adult-use marijuana, they are seeking narrower protections for only medical marijuana patients.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court ruling in Bruen has opened the door for challenges to many firearm restrictions, including the federal prohibition on cannabis users owning guns. Three different federal courts have struck down 18 U.S.C. §922 (g)(3) as unconstitutional using the standard set in Bruen, with one of these cases waiting for potential Supreme Court review. The Supreme Court’s pending decision in United States v Rahimi will potentially clarify any limitations on the application of the Bruen test and could illuminate the path forward in the cases highlighted in this blog post. At least until then, many Americans will have to choose between gun ownership and cannabis consumption.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Heather Trela is director of operations and fellow at the Rockefeller Institute of Government