Drug use is not confined to the United States and issues associated with drug use in the US spill over the borders and vice versa. COVID-19, too, does not respect borders. To learn more about what is happening with drug use at the USA-Mexico border, we talked to Jaime Arredondo, a professor in the Drug Policy Program at the Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas (CIDE), whose research spans HIV, policing, and injection drug use. Arredondo is involved with two harm-reduction organizations: one in the city of Tijuana (Prevencasa) and one in Mexicali (Verter). Harm reduction is an approach that promotes policies and programs to minimize harms associated with drug use without requiring people to minimize or stop using drugs. Harm reduction interventions may include needle exchanges, testing to identify contents of drugs, and safe-injection sites (among others). Mexico has a robust experience with harm reduction, beginning with a community-based organization’s syringe exchange program in Ciudad Juárez (Compañeros) in 1988 and continuing with the federal government’s 2003 statement in support of harm reduction. Syringe exchange programs have been created in states across the country. Nonetheless, harm reduction capacity has been greatly reduced due to the current Mexican federal government’s policies and has been further complicated by COVID-19.

Here we cover highlights from our conversation with Arredondo. The interview has been edited for readability. For other interviews on what the epidemic in a pandemic looks like see our series.

What was happening with drug use in Mexico prior to COVID-19?

According to Arredondo, in the past two to three years, there has been an increase in fentanyl use and an increase in overdoses for people who inject drugs. Unfortunately, the new federal administration, elected in 2018, does not support long-standing community-based organizations’ (CBO) harm reduction programs. The federal government cut all funding for nongovernmental organizations—including those focusing on women’s rights, human rights, and harm-reduction services—under the theory that the government would administer services itself. But the government hasn’t done that.

“Bureaucracy is painful.”

Instead, the previously imperfect system—which funded programs annually but only for nine out of 12 months, leaving a three-month gap every year—has been replaced by “a 12-month gap, which is not good.” Many nongovernmental organizations shut down. The country went from having 10 active needle-exchange programs to four: one in Tijuana, one in Ciudad Juárez, one sporadically in Chihuahua City, and one in Mexicali. Other organizations reduced the services they provide. Arredondo says that people who go into harm reduction do not do it to get rich; they have a deep commitment to their community and the people who access their services, as opposed to the vision that the current government has around CBOs. It is hard to find and afford supplies; at least 60 percent of the federal grants were dedicated for this purpose.

Location of Mexican Needle-Exchange Programs

Where can nongovernmental organizations get syringes, which are expensive and scarce under the COVID-19 emergency? Where can they find the opioid reversal drug naloxone (Narcan)? Organizations used four strategies to adapt to limited funding. Some survived on the surplus from previous years. Syringe exchange programs reduced the number of needles they dispensed to each individual from five to one per day. Other organizations used new funding from research projects to make up for deficits and allow research on program effects to move forward. Finally, organizations relied on donations from Canada and the United States. But even the generosity of these donors proved challenging because it is difficult to get donations of syringes and naloxone from the United States into Mexico. “We need to remember that naloxone continues to be a prescription only medicine in the country, just as it was several years ago in the United States.”

Arredondo sums it up: “Bureaucracy is painful.”

What happened during COVID-19?

Although Mexico has a long history of harm reduction, the federal policies in place immediately prior to the pandemic, which cut off funding to nongovernmental organizations, along with the increased availability of deadly fentanyl already presented harm-reduction organizations with serious challenges. Along came COVID-19, which Arredondo says took up all of the oxygen for public attention. People aren’t talking about drug use anymore, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t happening. Numbers available from Canada and the United States show increasing overdose deaths; the latest data from the US Centers for Disease Control show 2019-20 was the deadliest year ever for US overdose deaths. Harm-reduction programs, like needle exchanges, faced increased global demand for syringes due to COVID-19 and fewer financial resources to procure supplies like naloxone.

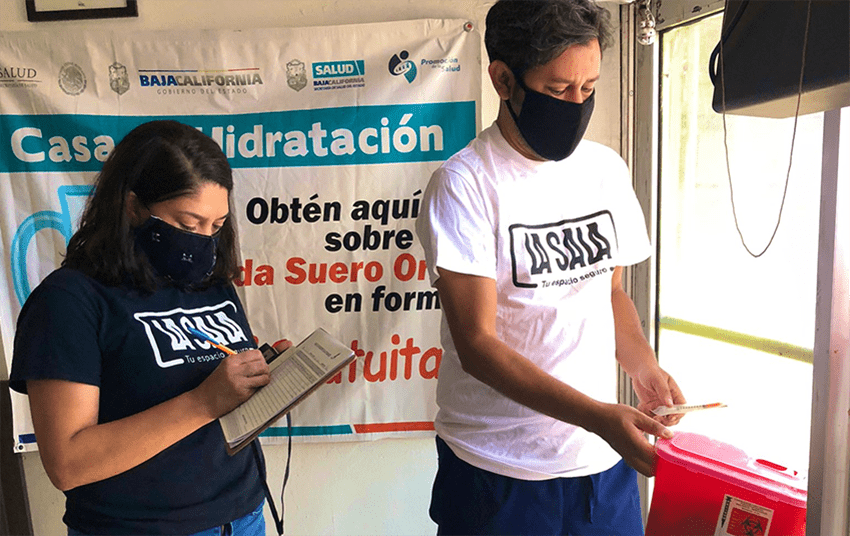

For the first three months of the pandemic, community-based harm reduction organizations had to reduce the number of days providing services. Where once they were staffed Monday to Saturday, without money for personnel they had to rely on volunteer schedules. Burnout has been through the roof, a topic that is not as studied as in other settings like Canada and the United States. The organizations that Arredondo works with were able to keep their doors open at least two times a week for the first three months of the pandemic. They modified best practices from other places about what to say to clients (for example, to not share drug supplies). They procured protective gear for the team. They redesigned services around minimal contact, putting up glass barriers at the front desk and prepackaging supplies.

The harm reduction clinic in Tijuana, Prevencasa, was able to implement standard COVID-19 detection procedures like temperature checks and a questionnaire about symptoms. With local officials, the clinic was able to create a shelter for people who use drugs who were assumed to be COVID-19-positive. They provided medication-assisted treatment so residents wouldn’t feel the need to leave. It was successful. As summer came and COVID-19 rates plummeted, local officials believed it was no longer needed. The shelter closed, but the organization is working on documenting the benefits of the intervention, so it could be replicated in other low-resource settings.

Harm-reduction programs, like needle exchanges, faced increased global demand for syringes due to COVID-19 and fewer financial resources to procure supplies like naloxone.

The Mexicali community-based organization Verter had fewer resources and just four people to manage the women’s only safe-consumption service and syringe program. The site saw a drop in the number of people attending, partly due to officials having urged residents to stay home (although many people do not have homes), and also an active policy around forced treatment—or the involuntary commitment of people who use drugs into abstinence-only treatment—implemented by City Hall. Also, Arredondo speculates that attendance in both organizations could have gone down as people were “not going to walk blocks–city blocks–to just go for one syringe. It’s just a waste of time,” as people are afraid of arbitrary detention by police forces that might result in confiscation of supplies and police harassment.

Around the middle of summer, harm-reduction services began to open up again with proper COVID-19 measures, but by winter increasing COVID-19 cases and decreased access to supplies again made it harder to help people through harm reduction. More and more people were overdosing and people on the frontlines did not have the necessary supplies, like naloxone, to react properly. Many times, police and EMT services go first to the organizations to get help for dealing with overdoses in their neighborhood. They’ve managed the best they can, but it is frustrating to try and frustrating not to succeed in saving a life.

What changes need to happen?

Arredondo wants to use the principles of harm reduction to address policy, too. He’d like to tell the Mexican government, “if you’re not going to help” address the problems he and his colleagues are facing, “don’t get in the way,” a.k.a the “Do Not Harm” strategy. He suggests:

- Legal mechanisms to allow supplies—like syringes and naloxone–to cross the border more seamlessly and free of taxes.

- Providing the legal mechanisms to allow CBOs to give services, such as safe consumption sites and community drug checking, without fear of prosecution and a source of stable funding.

- Rescheduling naloxone to allow it to be dispensed without a prescription (as it is in the United States) as a first necessary condition, but not sufficient, to deal with overdoses. The Mexican Congress is already looking into it, but the law needs to mandate the national commission against drug use (CONADIC) to develop a national strategy to provide free naloxone to CBOs and people who use drugs in the country.

- Raising awareness that drug use is still happening and it is still dangerous under a failed decriminalization framework. COVID-19 has exacerbated the barriers and challenges that people who use drugs face, at the same time it has taken attention away from drug policy challenges. Just because we don’t talk about other problems doesn’t mean they don’t exist.

Conclusion

Arredondo says that COVID-19 showed how interlinked the US and Mexico are through the close connection between cities on either side of the border: Tijuana/San Diego and Mexicali/El Centro. People travel regularly between the two countries, “COVID doesn’t respect those borders.” Substance use, too, does not stop at the border. It travels freely between the two countries. Arredondo has a paper showing prescribing habits in Mexico and the noticeably high opioid prescription rates in Mexican cities near the border—the result of US medical (drug) tourism. If the fates of the United States and Mexico are linked, Arredondo hopes that the US government can put substance use back on the radar for both countries.

To learn more about the work that Arredondo and colleagues are doing in Mexico, see this video on harm reduction strategies in the Mexican context and the “Juárez Declaration.”

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Patricia Strach is a fellow at the Rockefeller Institute of Government

Elizabeth Pérez-Chiqués is a fellow at the Rockefeller Institute of Government

Katie Zuber is a fellow at the Rockefeller Institute of Government