April 25, 2019

One of the most effective arguments for the legalization of marijuana is the economic opportunity it would create for New York State and its residents. Previous studies have found that 63.4 percent of surveyed adults agree that the creation of the industry and corresponding jobs would be a justification for legalization.[1] The legalization of marijuana provides an interesting case study and natural experiment in the field of economic development. It is rare that new industries and supply chains must be created in such a short time frame.

In this policy brief, we explore the legalization of adult cannabis use from an economic development perspective, including how the adult-use marijuana industry in New York would form and the types of firms that would emerge. We study the experiences of other states that have legalized adult-use cannabis to estimate job creation and the economic impact of legalization in New York.

The New York State Department of Health estimated the marijuana market size to be between $1.7 and $3.5 billion.[2] Our analysis found that a $1.7 billion industry could generate a total economic output of $4.1 billion and total employment of 30,700. It could also attract hundreds of millions of dollars in capital investment shortly after legalization as investors pour in to take advantage of the new market.

Our analysis found that a $1.7 billion industry could generate a total economic output of $4.1 billion and total employment of 30,700. It could also attract hundreds of millions of dollars in capital investment shortly after legalization as investors pour in to take advantage of the new market.

Before legalizing adult-use marijuana, there are many important factors that complicate the development of the industry which must be considered, especially restrictions by the federal government (see the Rockefeller Institute’s “Clash of Laws: The Growing Dissonance between State and Federal Marijuana Policies”[3]). If legalized, a state economy must establish a complete industry infrastructure and supply chain in a very short period of time. Because federal restrictions prohibit interstate movement of marijuana, the supply chain must be contained entirely within state borders, which means the impacts of the industry are also contained within the state.

In states that have legalized adult-use cannabis, the industry is heavily regulated and monitored. All firms participating in the commercial cannabis supply chain must be licensed, making it relatively easy to track the industry development and the establishment of businesses. Table 1 shows the licensing requirements of marijuana-related businesses in the states that have implemented adult-use retail.

| DESCRIPTION | CO | WA | OR | AK | CA | MA | NV | ||

| CULTIVATOR/ PRODUCER | Operates a facility to grow and harvest retail marijuana plants | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| MANUFACTURER/ PROCESSOR | Operates a facility that manufactures marijuana-infused products such as edibles, concentrates, or tinctures | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| TESTING | Operates a facility that conducts potency and contaminants testing for retail businesses | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| WHOLESALER | Buys marijuana and products in bulk and sells to retailers. | X | |||||||

| DISTRIBUTORS | Transports, tests, and packages for final sale at a licensed retailer. | X | X | ||||||

| RETAILER/DISPENSARY | Operates a business that sells marijuana to individuals. | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| TRANSPORTATION | Provides transport and temporary storage services to retail marijuana businesses | X | X | ||||||

| MICROBUSINESSES | May distribute, manufacture, and retail in a space < 10,000 sq. ft. | X | |||||||

| OPERATOR | May contract with a business to run operations. | X |

*All license regulations are current as of April 2019. Given that this is a dynamic industry, state licensing requirements are subject to change.

Colorado: https://www.colorado.gov/pacific/enforcement/retail-marijuana-business-license-application

Washington: https://lcb.wa.gov/mjlicense/marijuana-licensing and https://lcb.wa.gov/mj2015/testing-facility-criteria

Oregon: https://www.oregon.gov/olcc/marijuana/Pages/Recreational-Marijuana-Licensing.aspx

Alaska: https://www.commerce.alaska.gov/web/amco/MarijuanaLicenseApplication.aspx

California: https://www.bcc.ca.gov/clear/forms.html

Massachusetts: https://mass-cannabis-control.com/

Nevada: http://marijuana.nv.gov/Businesses/GettingALicense/

Maine and Michigan have both voted to legalize adult-use cannabis, but the regulations are still being drafted. Vermont has legalized adult use, but banned retail sales. These states have not been included.

Source: Rockefeller Institute of Government. Compiled from state marijuana control websites in March 2019.

Because federal restrictions prohibit interstate movement of marijuana, the supply chain must be contained entirely within state borders, which means the impacts of the industry are also contained within the state.

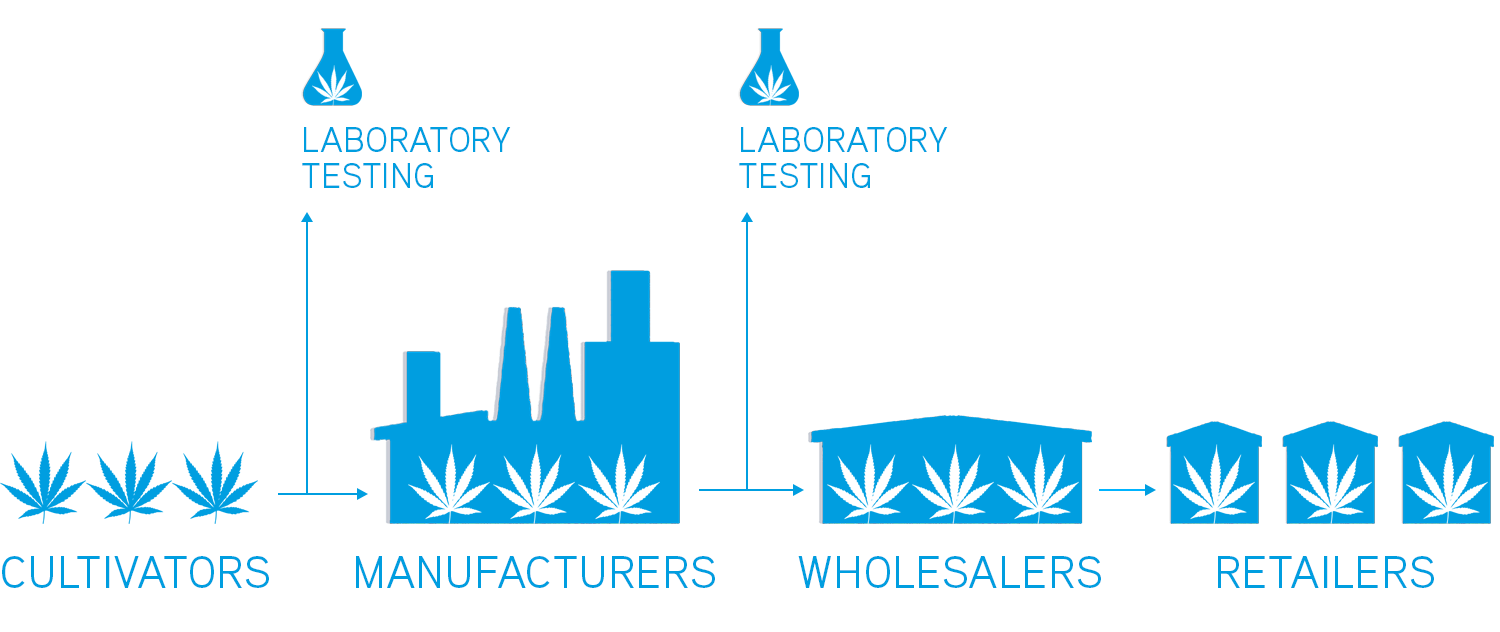

Every state with a retail system has identified and licensed four types of firms in the supply chain: cultivators, manufacturers, retailers, and testers. The flow of the product between these firms varies by state. Colorado and Washington have also awarded business licenses to transportation firms responsible for moving product from licensee to licensee. California and Nevada have designated distributors to manage the supply chain and transportation. Some states also issue licenses or permits to individuals working in the cannabis industry or cooperatives. Because these are not commercial entities, they have not been included in the table.

States have a range of policies related to vertical integration — the degree to which firms are allowed to control the various stages of the supply chain. Massachusetts has required vertical integration; firms are required to hold licenses for cultivation, product manufacturing, and retail. Colorado and Oregon allow businesses to hold multiple types of recreational cannabis licenses, but do not require it. Washington has restricted vertical integration, limiting a licensee to only one type of license.[4]

New York legalized medical marijuana in July 2014, awarding the first five licenses a year later. An additional five were awarded in August 2017. Like Massachusetts, the New York medical marijuana supply chain is vertically integrated. Therefore, each of the 10 registered organizations maintains one manufacturing facility where they cultivate and manufacture a legally allowable final product and operate up to four dispensaries across the state as allowed under the state license. A total of 32 of the 40 allowable dispensaries are operational.[5] Product testing has been conducted by the New York State Department of Health’s Medical Marijuana Laboratory and New York is working to identify independent laboratories certified to conduct the testing for potency and contaminants.

The plan outlined in the FY 2020 New York State Executive Budget[6] to legalize adult-use cannabis identifies a three-tier market structure based on the model to regulate alcohol in New York. Unlike New York’s medical marijuana program, the proposed adult-use bill explicitly prevents vertical integration. Proponents of a vertically disintegrated market structure, like that proposed in New York, believe that it expands economic opportunity to more vendors. The currently registered medical marijuana providers may be well positioned to operate as cultivators in the adult-use market, as they are the only firms with the existing infrastructure required to supply the market in a short time frame.

If New York were to establish licensing similar to the state alcohol industry, we could expect a supply chain made up of cultivators, manufacturers, wholesalers, testers, and retailers. Figure 1 shows one possible supply chain structure.

Recent market research reports have published estimates for the US marijuana market. In 2018, national employment for the marijuana market was in the range of 121,000 to 150,000. These numbers represent full-time equivalent (FTE) employees in both recreational and medicinal marijuana at all points of the supply chain. Table 2 compares estimates from three recent reports.

DATA CHALLENGES IN STUDYING THE CANNABIS INDUSTRY

Because the federal government does not allow the sale or use of marijuana, they do not acknowledge the existence of the growing industry in traditional data sets. The Census Bureau, Bureau of Economic Analysis, Internal Revenue Service, and Bureau of Labor Statistics aggregate firm data based on a firm’s North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) code. The NAICS system has yet to include categories related to cannabis. While firms in the legal cannabis industries are required to respond to surveys and submit tax returns, they must identify a NAICS code that best suits their primary businesses. Dispensaries, manufacturers, and cultivators choose categories such as Other Food Crops Grown Under Cover, Medicinal and Botanical Manufacturing, Miscellaneous Store Retailers, and Pharmacies and Drug Stores. Since Canada legalized cannabis in 2018, Statistics Canada has created classifications for firms in the industry.[7] A similar framework could be integrated into the NAICS system when the system is scheduled to be reevaluated and revised in 2022.

Market research firms, which tend to be pro-legalization, have used proprietary methods to estimate existing employment and output within the marijuana industries. These methods are based on state-level employment and sales data, and surveys of business owners and industry experts

| BDS ANALYTICS | LEAFLY | MARIJUANA BUSINESS DAILY | |

| 2016 | 89,500 | ||

| 2017 | 120,000 | 90,000-110,000 | |

| 2018 | 121,000 | 146,161 | 120,000-150,000 |

| 2019 | 211,000 | 170,000-210,000 | |

| 2020 | 210,000-255,000 | ||

| 2021 | 291,500 | 255,000-310,000 | |

| 2022 | 310,000-375,000 |

*Annual Marijuana Business Factbook, 6th Edition (Lakewood: Marijuana Business Daily, 2018); BDS Analytics, US Legal Cannabis: Driving $40 Billion Economic Output: Cannabis Intelligence Briefing (San Francisco: Arcview Market Research and Boulder: BDS Analytics, 2018); Bruce Barcott with Beau Whitney, Special Report: Cannabis Jobs Count (Seattle: Leafly, March 2019), https://d3atagt0rnqk7k.cloudfront.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/01141121/CANNABIS-JOBS-REPORT-FINAL-2.27.191.pdf

Sources: BDS Analytics, Leafly, and Marijuana Business Daily.

Some states have also released data on employment in their jurisdictions collected from licensed establishments. These data are preferred to national estimates because they are direct counts of workers and employment, and the methodology used to collect data is detailed. In 2015, Colorado issued 26,929 employment badges (full-time workers, part-time workers, owners, managers) and a report published by the Marijuana Policy Group (MPG) estimated that the companies in Colorado directly employed the 12,591 FTE workers. Washington data count 6,227 FTE employees in 2016, and Oregon has issued 12,500 employment licenses and counted 5,776 FTE employees in 2017.[8]

Table 3 shows the number of jobs created in states that have collected information to date. To allow for direct comparison, we standardized the number of FTE jobs created per $1 million in expected revenue per year. When considering the total employment and sales in the states, the average number of cannabis employees is 12.4 per $1 million in revenue.

| FTE Employment | Sales Revenue (in millions) | FTE Employment/$1 million in revenue | Average Hourly Wage | |

| Colorado (2015) | 12,591 | $996a | 12.6 | n.a. |

| Washington (2016) | 6,227 | $502b | 12.4 | $13.44 |

| Oregon (2017) | 5,776 | $520c | 11.1 | $12.13 |

[a] Miles Light et al., The Economic Impact of Marijuana Legalization in Colorado (Denver: Marijuana Policy Group, October 2016), http://www.mjpolicygroup.com/pubs/mpg%20impact%20of%20marijuana%20on%20colorado-final.pdf

[b] Washington Liquor Control Board, Fiscal Year 2016 Sales and Excise Tax by County — Retail sales only, accessed April 19, 2019, https://lcb.wa.gov/records/frequently-requested-lists

[c] Calculated from data included in 2019 Recreational Marijuana Supply and Demand Legislative Report (Portland: Oregon Liquor Control Commission, January 31, 2019): 8, https://www.oregon.gov/olcc/marijuana/Documents/Bulletins/2019%20Supply%20and%20Demand%20Legislative%20Report%20FINAL%20for%20Publication(PDFA).pdf

Source: Rockefeller Institute of Government and state cannabis revenue reports.

Colorado and Washington offer breakdowns of the total employment by supply chain category. In 2015, 35 percent of Colorado’s 12,591 cannabis FTEs were employed at retail operations. Adult-use dispensaries hire “budtenders” and other professionals. The cultivation sector of the industry made up 12 percent of employment. Cultivators employ “trimmers” and agricultural specialists. Sixteen percent of employment was in the manufacturing sector. The remaining 37 percent was distributed across administration and management, which would include testing, oversight, packaging, security, and other overhead expenses. A breakdown of the Washington cannabis labor force found 38 percent of the employees worked in retail dispensaries and 62 percent worked in cultivation and production businesses. Based on these two states, we could assume that approximately 35 percent of the New York cannabis workers would be in cannabis dispensaries and the remaining would be distributed across the rest of the supply chain.

Forecasting the economic impact of adult-use cannabis requires making assumptions about the potential size of the market. A recent report by the New York State Department of Health[9] assessed the potential impact of the regulated cannabis market in New York State. The authors reviewed data on marijuana usage and black market pricing for the state to identify a low range estimate of $1.7 billion and a high range estimate of $3.5 billion. The report then used these market sizes to forecast potential tax revenues. For consistency and ease of comparison with other New York-based reports, we adopt the same market-size assumptions for our analysis.

MARKET SIZE

“Based on inputs and assumptions, purchases of illegal marijuana in NYS are estimated to be about 6.5 to 10.2 million ounces annually. At an average retail price of $270 per ounce, the market for marijuana is estimated to be approximately $1.7 billion; at $340 per ounce, the market is estimated to be approximately $3.5 billion.”

— New York State Department of Health

As seen in Table 3, state employment reports show that across the three states there are 12.4 employees per $1 million in sales of adult-use cannabis. A $1.7 billion market in New York could directly employ approximately 21,080 employees in cultivation facilities, manufacturers, testing laboratories, and retail dispensaries. If New York’s market reaches $3.5 billion, direct employment could be 43,400. To put these numbers into perspective, the adult-use marijuana industry would be larger than New York’s burgeoning craft brewing production, including the related tourism, food service, and distribution industries which currently employ 13,000 workers directly.[10] Cannabis would be smaller than the state’s wine and related tourism industry which employs 62,450 employees.[11]

The impacts of the industry will continue to multiply as they flow through the New York economy. The marijuana industry will purchase additional supplies from New York-based suppliers and the people employed in the industry will spend their earnings in their local economies. Multiplier analysis is commonly used to estimate the wider-reaching economic impacts of industrial activity. However, there are two challenges to consider when using traditional multiplier tools to evaluate the impact of the cannabis industry that could lead to the underestimation of the industry’s impact through multiplier analysis:

IMPLAN software was used to calculate the potential impact of the development of three industries: cultivation, manufacturing, and dispensaries. Because the software does not include marijuana industries, the closest related sectors were selected. Table 4 shows the total impact of $1.7 billion in marijuana sales in the three new industries on the New York economy. The total impact figures include the economic activity of the cannabis firms, the additional activity in the supply chain, and employee spending in the economy.

| CLOSEST SECTOR | TOTAL EMPLOYMENT | ECONOMIC OUTPUT (IN MILLIONS) | |

| CULTIVATION | Greenhouse, nursery, and floriculture production | 2,145.4 | $ 190.4 |

| MANUFACTURING | Medicinal and botanical manufacturing | 5,149.7 | $ 1,522.7 |

| DISPENSARIES | Miscellaneous store retailers | 16,451.9 | $ 1,491.7 |

| TOTAL | 23,747.0 | $ 3,204.8 |

Source: Rockefeller Institute of Government

The estimates of 23,747 jobs and $3.2 billion in economic output represent a lower bound. The economic output is the goods and services generated in New York as a direct or indirect result of the creation of a commercial cannabis industry. The $3.2 billion would be equivalent to 0.2 percent of New York’s gross state product in 2017. The multipliers assume that a portion of the goods and services used in the industry will be imported from outside of New York, which means a portion of the economic impact will trickle outside of state lines. Because federal restrictions require that much of the supply chain be located within the state, it is likely that total economic impact will be higher than $3.2 billion.

The consulting group MPG has developed proprietary cannabis input-output tables and calculated related multipliers to address the limitations of traditional multiplier analysis. They calculate a marijuana retail multiplier of 2.398, which is significantly higher than the retail trade average of 1.844. MPG’s multiplier analysis suggests that Colorado’s $996 million in sales generated $2.39 billion in economic impact and supported 18,005 jobs. If these multipliers were applied to New York, the potential economic impact would be over $4 billion.[12]

| MARKET SIZE | $1.7B | $3.5B |

| TOTAL JOBS | 30,731.4 | 63,270.6 |

| TOTAL OUTPUT (IN MILLIONS) | $4,079.3 | $8,399.6 |

Based on more conservative market-size estimates, traditional multiplier analysis finds the recreational marijuana industry would generate at least $3.2 billion in economic output and support 23,747 jobs. It is likely that this approach underestimates the impact of the emerging cannabis industries. Multipliers that adjust for the cannabis industries’ constraints find an impact of 30,731 jobs and $4.1 billion.

Adult-use cannabis in New York would require capital investments in large-scale cultivation facilities across the state. Etain, LLC, is planning a medical marijuana manufacturing facility in Warren County, New York. This $9 million investment would be in addition to its existing $4 million grow center.[13] At least one additional firm is pursuing building a $200 million cultivation facility in Buffalo.[14]

All medical marijuana cultivation and manufacturing facilities in New York are currently located in Upstate New York. This geographic trend will likely continue since these facilities tend to have large footprints and need lower-cost water and energy inputs. New York should expect a temporary economic boost from the large-scale investments made shortly after legalization.

The estimates above have been based on a statewide rollout of the recreational cannabis industry. The current proposal would allow all counties and cities with a population larger than 100,000 to pass a local resolution that would prohibit marijuana growers, manufacturers, and retailers from operating within the borders. As of April 2019, Suffolk, Nassau, Rockland, Putnam, and Chemung counties were weighing legislation to opt out and were considered likely to ban sales in the event of legalization, and North Hempstead has already passed legislation banning the sale of recreational marijuana.[15] Municipalities could not ban possession and personal use; residents would be allowed to purchase marijuana in another county to store and use in their homes.

The recent experience in Massachusetts suggests that many communities will choose to opt out or delay rollout. The state’s first two recreational dispensaries opened in November 2018. By the end of October 2018, 80 communities in the state had enacted a ban on recreational marijuana retail. Another 110 had placed a temporary moratorium on commercial cannabis that would allow them to further consider the issue or enact zoning rules.[16]

Given the current infancy of the industry, there is no evidence available on the economic impact of municipal opt-outs. New York municipalities that have chosen to opt out would not directly benefit from the job creation associated with the new industry and forfeit their share of any marijuana tax revenue. Depending on the geographic distribution of the opt-out, residents could still pursue cannabis employment in neighboring counties. The potential impact on statewide revenue is dependent on the geographic distribution of municipal bans. A handful of counties sporadically distributed could have minimal impact because customers could access dispensaries in neighboring counties. If a large cluster of municipalities, such as both counties on Long Island, choose to opt out, it could make it more challenging for residents to acquire legal cannabis and drive down demand. It remains to be seen if community opt-out has a significant impact on the development of the commercial cannabis industry or just alters the geographic distribution of operations within the state.

While legalization could create jobs in the cannabis industry, it could endanger others. The federal government requires many employers to implement drug-free workforce policies or carry out regular drug testing.

In 2018, the New York labor force had 181,600 employees working in the transportation sector and an additional 1,488,900 workers in federal, state, and local governments. Workers in law enforcement, emergency responders, aviation, trucking, railroads, and mass transit are subject to federally mandated marijuana testing. These numbers do not include the individuals who work for government contractors and grantees such as universities, colleges, and hospitals — all of whom are subject to drug-free policies that prohibit the use of marijuana.[20]

As states legalize marijuana, we’re beginning to see results in workplace drug tests. Data published by Quest Diagnostics found that the number of positive drug tests in Nevada and California increased by 43 and 11 percent, respectively, after legalization.[21] Employees with increased drug usage in workplaces with zero-tolerance policies may find themselves endangering their employment. There are currently no data available on the number of individuals terminated and a number of legal challenges to these policies have resulted. Researchers and policymakers will continue to track the development of these policies and testing requirements as the cannabis industry emerges.

The development of any new industry attracts investments and creates jobs. Legalization of adult-use cannabis in New York will create jobs in cultivation, manufacturing, and retail sectors. Forecasting the impact of cannabis-related economic development is challenging due to lack of data and long-term observations of the policy impacts. Depending on the multipliers used and based on the early experiences of other states, we estimate 23,700 to 30,700 cannabis-related jobs could be created annually in a $1.7 billion market in New York. The total economic output generated could be as large as $4 billion. This number would be impacted by local jurisdiction decisions to opt out of the market or changes in federal marijuana policies.

It is important to remember that this is just one element of a comprehensive economic impact analysis. For example, the fiscal impacts on the state through tax and licensing revenues must be considered and will be discussed in a forthcoming brief. A complete economic-impact assessment would also consider the impact of fiscal costs associated with adult-use cannabis.

NOTES

[1] Emma E. McGinty et al., “Public perceptions of arguments supporting and opposing recreational marijuana legalization,” Preventive Medicine 99 (June 2017): 80-6.

[2] Assessment of the Potential Impact of Regulated Marijuana in New York State (Albany: NYS Department of Health, July 2018): 18, https://www.health.ny.gov/regulations/regulated_marijuana/docs/marijuana_legalization_impact_assessment.pdf

[3] Heather Trela, Clash of Laws: The Growing Dissonance between State and Federal Marijuana Policies (Albany: Rockefeller Institute of Government, January 25, 2018), https://rockinst.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Clash-of-Laws_Marijuana-Policy_FINAL.pdf

[4] Anne van Leynseele, “Washington: Vertical Integration: What It is and Why It Matters to Cannabis,” Cannabis Law Journal, accessed April 19, 2019, https://journal.cannabislaw.report/washington-vertical-integration-what-it-is-and-why-it-matters-to-cannabis/

[5] “Registered Organization Locations,” NYS Department of Health, revised April 2019, https://www.health.ny.gov/regulations/medical_marijuana/application/selected_applicants.htm.

[6] “FY 2020 New York State Executive Budget, Revenue Article VII Legislation, Part VV,” accessed April 2, 2019, https://www.budget.ny.gov/pubs/archive/fy20/exec/artvii/revenue-artvii-ms.pdf

[7] Classifying Cannabis in the Canadian Statistical System,” Statistics Canada, accessed April 23, 2019, https://www.statcan.gc.ca/eng/subjects/standard/cannabis/cannabis

[8] Miles Light et al., The Economic Impact of Marijuana Legalization in Colorado (Denver: Marijuana Policy Group, October 2016), http://www.mjpolicygroup.com/pubs/mpg%20impact%20of%20marijuana%20on%20colorado-final.pdf; Chasya Hoagland, Bethanne Barnes, and Adam Darnell, Employment and Wage Earnings in Licensed Marijuana Businesses, Document Number 17-06-4101 (Olympia: Washington State Institute for Public Policy, revised June 29, 2017, for technical corrections), http://www.wsipp.wa.gov/ReportFile/1669/Wsipp_Employment-and-Wage-Earnings-in-Licensed-Marijuana-Businesses_Report.pdf; Beau R. Whitney, Cannabis Employment Estimates: House Committee on Economic Development and Trade (Portland: Whitney Economics, February 22, 2017), https://olis.leg.state.or.us/liz/2017R1/Downloads/CommitteeMeetingDocument/99775

[9] Assessment of the Potential Impact of Regulated Marijuana in New York State, p. 18.

[10] “Facts,” NYS Brewers Association, accessed April 19, 2019, https://newyorkcraftbeer.com/facts/

[11] The Wine Industry Boosts the New York Economy by $13.8 billion in 2017 (Washington, DC: WineAmerica, 2017), https://www.newyorkwines.org/Media/Default/documents/New%20York-Report.pdf

[12] Light et al., The Economic Impact of Marijuana Legalization in Colorado.

[13] Liz Young, “Medical marijuana manufacturer plans a $9 million expansion in Warren County,” Albany Business Review, October 3, 2018, https://www.bizjournals.com/albany/news/2018/10/03/medical-marijuana-manufacturer-plans-9-million.html

[14] “California marijuana company plans $200 million campus in New York,” Marijuana Business Daily, January 14, 2019, https://mjbizdaily.com/california-marijuana-company-campus-new-york-state/

[15] Rebecca C. Lewis, “Which counties just say ‘no’ to marijuana?,” City and State New York, April 2, 2019, https://www.cityandstateny.com/articles/politics/new-york-state/new-york-counties-opposed-to-legalizing-recreational-marijuana.html; Khristopher J. Brooks, “North Hempstead votes to ban sale of marijuana for recreational use,” Newsday, updated January 16, 2019, https://www.newsday.com/long-island/nassau/north-hempstead-marijuana-ban-1.26010011

[16] Ally Jarmanning and Daigo Fujiwara, “Where Marijuana Stores Can — And Can’t — Open in Mass.,”

WBUR, updated October 29, 2018, https://www.wbur.org/news/2018/06/28/marijuana-moratorium-map

[17] “Federal Contractors and Grantees,” Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), updated November 2, 2015, https://www.samhsa.gov/workplace/legal/federal-laws/contractors-grantees

[18] “Executive Orders: Executive Order 12564–Drug-free Federal workplace,” National Archives Federal Register, last reviewed August 15, 2016, https://www.archives.gov/federal-register/codification/executive-order/12564.html

[19] “Omnibus Transportation Employee Testing Act of 1991,” U.S. Department of Transportation, accessed April 19, 2019, https://www.transportation.gov/odapc/omnibus-transportation-employee-testing-act-1991

[20] “Current Employment Statistics – CES (National),” U.S. Department of Labor Bureau of Labor Statistics, accessed April 11, 2019, https://www.bls.gov/ces/

[21] “Workforce Drug Positivity at Highest Rate in a Decade, Finds Analysis of More than 10 Million Drug Test Results,” Quest Diagnostics, May 8, 2018 http://newsroom.questdiagnostics.com/2018-05-08-Workforce-Drug-Positivity-at-Highest-Rate-in-a-Decade-Finds-Analysis-of-More-Than-10-Million-Drug-Test-Results

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Laura Schultz is director of fiscal analysis and senior economist at the Rockefeller Institute of Government