March 29, 2016

In May 2015, the State University of New York (SUNY) Board of Trustees adopted a resolution directing Chancellor Nancy Zimpher to develop a plan to make applied learning opportunities available to SUNY students. While all applied learning experiences — work-based, service-oriented, or directed research are believed to strengthen the academic performance of students,internships are believed to improve employment outcomes on graduation. Research on the effects of applied work-based learning experiences on employment rates, salaries, and levels of job satisfaction suggests that such beliefs may be warranted. However, the findings from extant research often lack detailed information useful for program development and evaluation at department, campus, or system levels. Access to detailed and comprehensive administrative data has opened up the possibility to pursue continuous, systematic, and more refined assessments of the effects of applied learning. However, most studies using such data have not examined the effects of applied learning on retention, graduation, and labor market outcomes. To better judge the feasibility of using administrative

data to measure such effects, we conducted a pilot study of the effects of internships — one form of applied learning — at one SUNY campus. Working with experienced analysts in the field and New York State Department of Labor (NYSDOL) staff, as well as SUNY officials and administrators at the SUNY campus participating in this pilot study, we identified and addressed a range of design, measurement, and implementation matters. Findings and conclusions concerning the effects of internships on academic success (retention and graduation) are presented in the main report, Applied Work-Based Learning at the State University of New York: Situating SUNY Works and Studying Effects. In this supplement, we report findings on the feasibility of using extant academic unit records linked to NYSDOL Unemployment Insurance (UI) wage records to estimate the effects of internships on employment outcomes. Findings are presented and discussed, with due attention to the constraints of the pilot study itself and considerations in interpretation.

Overall, we find that the effects of internships on employment outcomes can be estimated with linked administrative academic-wage records. However, there are important design, measurement, and implementation considerations that limit the measures available and the strength and usefulness of the findings. An important limitation is that access to employment and wage information in the NYSDOL UI wage record files is, at present, available to SUNY only as data for groups of no less than ten graduates. Access to individual wage records, linked to administrative academic records, would extend and refine the kinds of analyses that could be carried out and, therefore, strengthen the confidence researchers and administrators could have in the results. A further, major limitation with respect to presently available information is incomplete coverage.

NYSDOL wage record information is limited to graduates who take up covered employment in New York State (NYS). Employment outcomes for graduates who leave NYS, who are self-employed, or otherwise not in covered employment are not known. The extent to which internships are associated with more or less favorable results overall cannot be estimated. Insofar as New York pursues data sharing agreements with other states in the region, this limitation can be reduced. With the data presently available, analyses can uncover associations of internships with likelihood of employment in NYS and level of wages of graduates employed in NYS. Those are narrower, but still relevant, measures of effects for SUNY and its campuses.

The measures of effects could be extended if campuses and programs had information on students who transfer out (to include, eventually, employment outcomes for such students) and who continue into graduate studies. If not available for every student or graduate, at least information on registrations and academic performance for students moving among SUNY campuses might be incorporated in analyses.

Academic records might be further extended, to include information collected in a systematic way on student participation in internships that do not come under a formal course. Initiatives with E-Portfolios might offer useful examples of approaches to obtain such information, at once complementary to and richer than what may be obtained from online surveys of students or graduates.

Another limitation is the lack of detailed information on internships — beyond course designation — to mark participation and credits earned. SUNY, and individual campuses, are developing and implementing means to assign to each course a classification according to the nature of the applied learning experience provided.

But, as noted in the main report, we lack additional details on features of internships, such as whether internships are integrated within a degree program, structured seminars are organized within the internship, faculty are directly involved, employers who host interns have ongoing relationships to the program, and whether assessments are geared to cognitive and noncognitive objectives. Under SUNY Guidelines, all approved applied learning experiences are expected to manifest features such as these.7 However, to the extent that the features differ within and among fields of study, they may be associated with differences in employment outcomes as well as retention and graduation rates. If so, such findings could target areas for change in the organization of and arrangements for internships.

Even lacking details on internship features, extant administrative academic unit data linked to UI wage record data could be used for the assessment of employment outcomes at program, campus, and system level. If UI wage record information were routinely appended to administrative academic records, changes over time in employment outcomes for internships can be tracked against the introduction or adaptation of particular internship features or different levels of participation at program or campus level. Department faculty, through other methods, could probe more fully what might account for changes (if any) in observed employment outcomes.

Beyond design, measurement, and implementation considerations, the analyses of employment outcomes yield two main findings of interest. One finding is that estimates of the effects of internship on employment outcomes are mixed — and, generally, more mixed than what we found for effects on retention and graduation as presented in the main report. The mixed findings may owe to data limitations, specifically the use of comparisons of groups of internship takers to groups of nontakers, as opposed to student-level analyses made possible with unit-record data. For analyses of the effects of internship taking on retention and graduation in the mainreport, we relied on mulitivariate statistical techniques as well aspropensity score matching. Or, the mixed results may simply reflect the reality of distinct labor markets for graduates from different fields. Labor market outcomes also reflect near-term dynamics in national and regional economies, having greater or lesser effects by sector or occupation. We do not fully account for such influences.

The second finding is that some results appear to be highly suggestive. In particular, we find generally consistent evidence that graduates in business with internships were more likely to be employed in NYS, more likely to find jobs in NYS sooner, and more likely to receive higher wages in NYS jobs than their peers without internships. We find less consistent evidence of differences in effects by personal attributes of graduates. We judge all results to be suggestive. Even for business graduates, not all of the differences associated with internship taking are statistically significant. In a few comparisons, for graduates from other fields or manifesting particular demographic or socioeconomic attributes, the pattern is reversed. Moreover, as already noted, the coverage of post-graduation experiences is incomplete and the measures of employment outcomes are limited to the period immediately following graduation. Finally, we don’t know enough to conclude that the internships let alone any particular features of the internships — account for observed results.

Administrative data, already collected by campuses and NYS, provide an opportunity to measure the impact of internship that may be utilized by campuses or systems. An important aim of the pilot study was to explore how far administrative academic unit records, linked to UI wage records, can be used to assess the effects of internships on employment outcomes. While such data increasingly are being accessed and used for studies of differences in employment rates and salaries by field for institutions and states, the pilot study is distinctive in its use of linked academic wage records to uncover the effects of a single program feature internship — within and across fields. We sought to explore the feasibility of such an approach, provide details on the measures available, and identify limitations and gaps. Although undertaken for one campus, the considerations and findings from this pilot study reveal the potential for, and limitations of, such an approach for other campuses and for SUNY.

General design, measurement, and implementation matters are addressed in the main report. We summarize and extend that discussion here, drawing out considerations in using linked academic-wage record data to assess the effects of internships on employment outcomes.

In approach, the employment outcomes of participants in applied work-based learning experiences need to be compared to the employment outcomes of graduates who did not have such experiences in the course of their studies. Graduates in these two groups may differ in individual or program attributes that are likely to be associated with their prior decisions to participate in internships and also may be associated with employment outcomes. So, the method used to uncover the effects of internship taking should take into account such attributes. Methods to dothis aim to address the problem of self-selection into internshps as well as to improve the accuracy of the estimation of the effects of the internship alone.

As developed in the main report, we judged a “matched” students strategy as the most appropriate method for the pilot study. Under such an approach, academic and socioeconomic information is used to “match” students (here, graduates), i.e., to identify those who are similar in the likelihood of participation in an internship. Employment effects of internships are then estimated by comparing the outcomes of those who participated in such experiences with those in the “matched” group. However, for the analysis of employment outcomes, we lacked access to the unit records needed in order to develop the “matches.” For this part of the pilot study, we could not implement the preferred method. While we had access to academic unit records for the pilot study and individual wage information could be linked to the academic unit record, only group data with linked academic-wage record information were made available to us. As a result, we worked with 176 groups of graduates, reducing to eighty-eight “pairs.” Each group within a “pair” has in common individual or program attributes but differs in participation in internships. We discuss this approach further under implementation considerations below.

Four considerations for the design of the pilot limit the analyses and bear upon interpretation.

Nonetheless, the results can provide meaningful information at campus and system levels, if interpreted narrowly as the effects of participating in an internship recognized by the program/campus as meeting academic requirements with respect to learning aims, learning experiences, and subject to academic oversight.

With this consideration in view, we worked closely with officials at the participating campus to identify fields in which internships are voluntary and with proportions of internship takers at neither extreme (very low or very high rates of internship taking). Of these fields, we further identified those for which the numbers of both internship takers and nontakers and of graduates were large enough to permit comparisons via “paired” groups. The selected fields are Biology, Business, Health Sciences, and Psychology. Graduates may have followed different degree plans/specializations within the field (B.A. or B.S., for example).

While such an approach allows us to examine the effects of participation in an internship, it reveals an important limitation for the use of available linked academic wage record data to analyze the effects of internships on employment outcomes. For fields in which internships are expected, required, or commonly pursued (and, equally, for fields in which none of these considerations apply), future analyses will need to be framed differently. Within fields expecting or requiring internships, for example, analyses might explore differences in employment outcomes by internship feature.11 With some exceptions, information of this type is not now routinely or systematically collected and entered into administrative databases.12 However, in fields or on campuses where arrangements for internships have changed, continuous and systematic monitoring of trends in employment outcomes using presently available linked academic-wage record data might provide indications of effects associated with such changes.

For the purposes of the analysis, we use three employment outcome measures: employed within NYS in any one of six quarters from the date of graduation (counted as employed in the quarter if wages exceed the minimum wage threshold); number of quarters until the first match (excluded, if wages are less than the minimum wage threshold); highest wages recorded in any of the first six quarters from the date of graduation (excluded, if the wages are less than the minimum wage threshold in all quarters).

Here, we elaborate on considerations for measurement raised in the main report, Applied Work-Based Learning at the State University of New York: Situating SUNY Works and Studying Effects.

Nonetheless, when considered with reference to the direct contribution to NYS’s workforce, observed differences by internship taking in the proportions of graduates employed in NYS, and in the earnings of those so employed, are themselves appropriate and relevant — if partial — measures of the effects of internships.

We understand that employer filings report wages paid during the quarter. Graduates who commence a full-time post at some point after the beginning of the quarter will have recorded wages at a level below the full-time equivalent rate. To address the issue, we chose to use the highest reported wage in any of the first six quarters following the date of graduation. The six quarter period allows for transition into employment, but is short enough to exclude most graduates who undertake and complete graduate studies (e.g., a master’s degree, but see “part-time employment” below).

Further, the wages recorded on UI unit records include bonuses or other compensation at the time of appointment. Since we use the highest reported wage in any of the first six quarters following graduation as the measure of earnings, bonuses or one-time additional compensation received in a given quarter give an estimate of pay above the rate for the year as a whole. For graduates taking up employment within six quarters of graduation, we believe that additional compensation at the time of employment is likely the greater of the two forms of these benefits. If so, such one-time additional compensation could occur in a “transition” quarter, i.e., a quarter when employment commences during, as opposed to at the beginning of, the quarter (e.g., employment begins in June, reference quarter begins in April; employment begins in September, reference quarter begins in July). Recorded wages for the “transition” quarter are less likely to be substantially above the wages for the first, full quarter in covered employment.

Finally, we anticipate that effects of internships may carry forward, indeed increase, over time. Small or no differences in the first postgraduation, six-quarter period cannot be taken as evidence that the effects of internships on employment outcomes do not appear or grow in five or ten years. Since we are working with three successive cohorts of entering students who graduate over a four-year period, we use the regional Consumer Price Index for Urban Wage Earners and Clerical Workers (CPI-W) to adjust all wages to 2014 dollars. Other studies adopt different approaches, each seeking to arrive at a better estimate of regular earnings over a year or for a typical quarter.

Graduates employed part-time, and notably those continuing graduate education with support from an assistantship, also appear on wage records. To exclude such graduates from the analysis — that is, to exclude from counts of employed (and from analyses of wages) any graduate other than those most likely to be in regular employment, we established a wage threshold corresponding to the minimum wage in NYS applicable to the relevant year. Here, too, other studies using wage record information adopt a similar approach.20 However, we note that the threshold, on an annual basis, of about $13,000 is below the stipend at many universities for a graduate assistant pursuing full-time studies.21

To the extent such graduates are included in the analyses, employment rates will be higher, and mean or median wages likely lower, in the fields of study so affected. Measures of internship taking and individual and program characteristics, taken from administrative academic records at the participating campus, are the same as those used in the the part of the pilot study concerned with the effects of internship on retention and graduation. For the purposes of this pilot study, a graduate who took at least one internship for academic credit during the course of their degree studies is considered an internship taker. As described in the main report, the majority of students with internships received credit for internship in more than one academic term, and most internships came later in the degree program. All other variables also are categorical: Academic program (Biology, Business, Health Sciences, Psychology, Other); gender (male/female); racial/ethnic group (White, Asian, Black, His panic, Other); SAT Math score (above median/below median); and tuition residency in first term (NYS/other).

As mentioned, our work with UI wage record information obliged us to follow a sequence of steps in order to conduct the study. We elaborate here on the main considerations.

Importantly, these decisions were guided by advice from officials at the participating SUNY campus who had close knowledge of the study programs concerned and the extent to which participation in internships is voluntary.

Adopting a conservative estimate that at least half of the Social Security numbers submitted for graduates would not be matched with NYSDOL’s wage records (for graduates not employed in a covered position, employed outside of NYS, employed part-time, in graduate study), we established 176 groups, identified by codes on the file to be submitted to NYSDOL. The groups represent eighty-eight “pairs” of groups of graduates for those who had internships and those who did not. The “pairs” were established by individual or program attributes (field of study, gender, racial ethnic group, Pell Grant eligibility, SAT Math score, NYS residence for tuition fee purposes). Measures of central tendency and spread for each of the three employment outcomes were obtained for each group within every “pair.” Groups were successively disaggregated, by one, two, three, four, and five attributes, in general trying to preserve a minimum cell size of twenty or greater in the constructed group. Four of the 176 groups returned a number of matches insufficient to permit reporting by NYSDOL.

A number of studies using linked academic-wage record data rely fully on descriptive statistics of the proportions employed and median wages (sometimes with associated measures of dispersion, such as the interquartile range or quartiles or deciles).23 The argument in favor of the median as a measure is that the influence of extreme values is minimized. Inspection of the descriptive statistics on wages reveals median wages are as much as 15 percent below the means for groups in which extreme (high) wages are recorded.

The statistical tests allow for a conservative approach to the interpretation of differences in employment outcomes between intern takers and non-takers. The results direct attention to “pairs” where differences in estimated effects are relatively large. Means and medians (as well as other descriptive statistics) are provided in the supplementary tables, and so can be consulted to examine all patterns as well as to identify groups and “pairs” where means and medians diverge.

We use descriptive data to explore the relationships between participation in an internship and employment outcomes, taking into account identified academic, demographic, and socioeconomic backgrounds of graduates.

Notwithstanding our reference to “effects,” the differences may not signal causal relationships. Even if participation in an internship is found to be associated with a higher likelihood of employment in NYS on graduation or higher NYS earnings, the associations may mask other causes for such favorable outcomes. For the analysis of retention and graduation effects (discussed in the main report), we relied on multivariate regression and propensity score matching (PSM) to support arguments of causality. While conceptually sound, the methods are limited to the extent that the most important observable attributes of graduates that determine their probability of internship taking are available. As acknowledged in the main report, we lack a number of observable measures for the regressions and PSM. We expect that unobservable measures (such as, motivation) are also important.

For the analysis of employment outcomes, we rely on comparisons of means. For the present analysis, we do not have available individual unit record data. Rather, we have obtained means (and other descriptive statistics) for identified “pairs” of groups, in each of which graduates have the same individual and/or program attributes but differ with respect to internship-taking. Supplementary tables in the Appendix provide descriptive statistics (Tables S.1 to S.4) and statistical results (Tables S.5 to S.8).

Overall, some 60 percent of graduates from the participating campus took up employment in NYS within six quarters of graduation. The proportions vary by field and program and individual attribute of the graduate. Details are provided in Supplementary Table S.5.

Overall, internship taking appears to be marginally associated with the likelihood of taking a job in NYS within six quarters of graduation. The overall mean difference, of 1.3 percentage points, is not statistically significant. For most academic, demographic, or socioeconomic attributes, the differences in proportions employed in NYS between internship takers and non-takers are relatively small, mostly insignificant, and suggest no particular pattern.

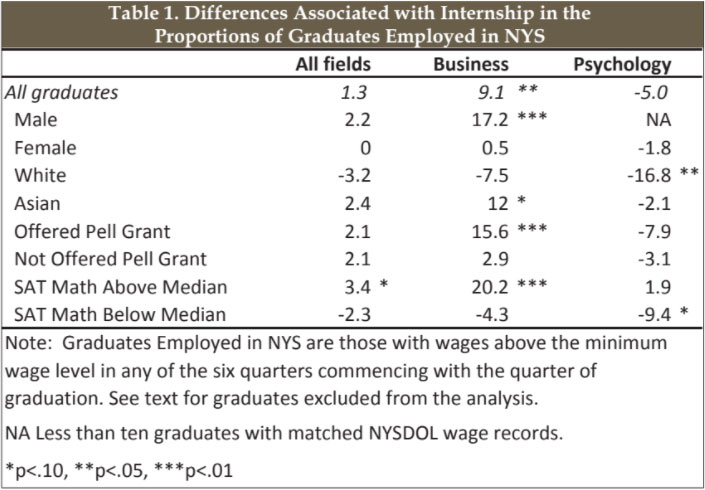

However, larger differences in NYS employment outcomes (as picked up in UI wage records) emerges particularly by field. Selected results are shown in Table 1 below for graduates in business and psychology. Details for other fields and attributes are provided in Supplementary Table S.2.

In particular, Business graduates who took internships are 9.1 percentage points more likely to have a job in NYS than their peers who did not participate in internships. The difference is statistically significant (p<.05), as is the 17.2 point difference associated with internship taking for Business graduates who are male (p<.01), the 12.0 point difference for Business graduates who are Asian (p<.10), the 15.6 point difference for Business graduates who were offered Pell grants in the first term (p<.01), and the 20.2 point difference for Business graduates with SAT Math scores above the median (p<.01). That is, internship taking is associated with NYS employment following graduation for Business graduates who differ for a number of academic, demographic, and socioeconomic characteristics.

In contrast, for Psychology graduates, the 5.0 percentage point difference in the proportions employed in NYS is not statistically significant. Further, for Psychology graduates with particular academic, demographic, or socioeconomic attributes, the effects of internship taking were mostly insignificant. For Psychology graduates who are White and who have SAT Math scores below the median, internship taking appears to be associated with a lower likelihood of NYS employment within six quarters immediately following graduation (-16.8 percentage points and -9.4 percentage points, respectively, p<.10 or lower).

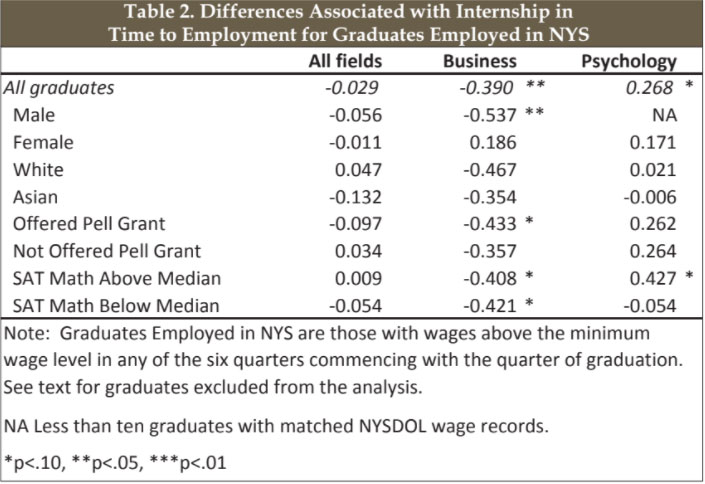

Turning only to those who took positions in NYS, the time between graduation and employment was an estimated 2.8 quarters, on average (median and mode, both two quarters commencing with the quarter of graduation). Overall, differences in the time to secure a NYS job appear to be little affected by internship taking. For all graduates, the mean difference is .03 quarters (roughly two days sooner). Details are provided in Supplementary Table S.7. However, looking again at results within fields of study, the time to NYS employment shows a somewhat larger association with internship taking. Selected results are shown in Table 2 below. Details for other fields and attributes are provided in Supplementary Table S.8.

In particular, internship takers assumed NYS jobs an estimated .39 quarters, or five weeks, sooner than non-takers, for Business graduates, but .27 quarters, or 2 weeks later, for Psychology graduates (p<.10 or lower). The overall findings suggest the effects of internship taking emerge by field, and may reflect program and labor market factors. In fact, the findings provide very little evidence that differences in time to NYS employment within each field are associated with academic, demographic, or socioeconomic attributes. The patterns for Business and Psychology graduates find broad parallels in time to NYS employment results for, respectively, Health Science and Biology graduates.

For those graduates who took up employment in NYS, quarterly wages (limited to those employed and earning above the minimum wage threshold in the reference quarter) differ by field, gender, racial/ethnic group, Pell grant eligibility, and SAT Math score. In particular, Business graduates, male graduates, graduates who received Pell grants in their first academic term, and graduates with SAT Math scores above the median show relatively higher quarterly wages reported by employers to NYSDOL. Simple descriptive statistics are provided in Table S.4.

No pattern emerges when NYS quarterly wages are compared overall for those graduates who had an internship and those without internships in the course of their degree studies. The overall comparisons may reflect, in part, the influence of extreme values within wage records. For all graduates employed in NYS following graduation, in the quarter with the highest wage among the first six following the date of graduation, internship takers received $9,115 on average (in 2014 dollars). For those without internship experiences during their degree programs, the average wage was $9,341. Using medians, internship takers recorded quarterly earnings of $8,183 while those who had no internship experiences showed median earnings of $7,934.

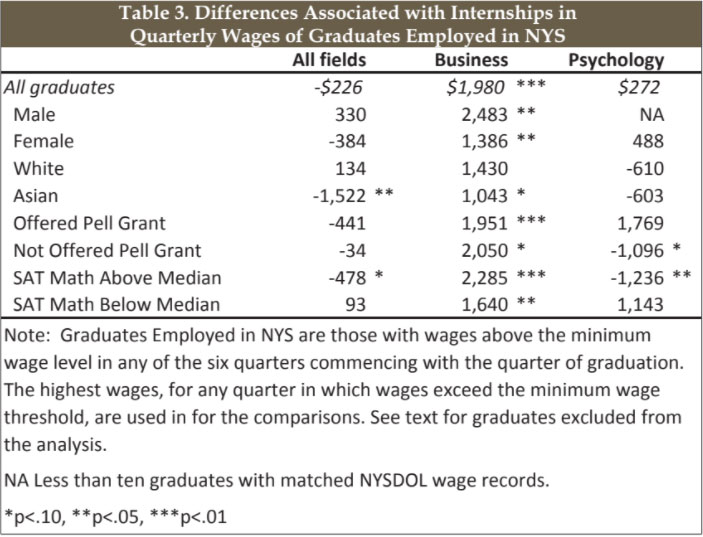

While there is no evident common pattern when NYS quarterly earnings (mean or median) are compared for each individual “paired” group, some differences emerge by field. Selected findings are presented in Table 3 below. Details for all fields and attributes are provided in Supplementary Tables S.7 and S.8.

For business graduates, those having had internships recorded wages roughly $2,000 (point estimate, $1,980) greater, on average, than wages recorded by their peers without internships (significant at p<.01). This difference is on the order of 10 percent, relative to average quarterly wages received, within the field. For Psychology graduates, the estimated difference in wages of $272 favoring internship takers is not statistically significant.

The relatively strong and favorable results for Business graduates who took internships largely holds across academic, demographic, and socioeconomic attributes. In particular, although the size of the difference in quarterly wages attributed to internships for Business graduates varies from $1,000 to $2,500, the effect is significant for both males and females, with or without a Pell grant offer, or SAT score above or below the median. For Psychology graduates, the association between internship taking and quarterly wages from employment in NYS following graduation is mostly weak and statistically insignificant. The exceptions appear for Psychology graduates with internship experiences who were not offered Pell grants or with SAT scores above the median.

In both instances, the comparisons show graduates with internships in this field recorded lower wages (on the order of an estimated $1,000 in the reference quarter) compared to their peers without internship experiences (p<.10 or lower).

The differences in the patterns of associations between internship taking and employment outcomes by field invite closer consideration of both the orientations of the programs and the destinations of graduates. The proportion of Psychology graduates with internships is lower than found for graduates in Business, and the proportion of Psychology graduates with and without internships employed in NYS following graduation is also lower than for their peers in Business. Although not revealed in the data available to us, graduates in Psychology may be more likely to pursue postgraduate study immediately following graduation (with employment outcomes manifested later).

To date, assessments of the effects of applied learning in general, and work-based applied learning in the form of internships in particular, on employment outcomes are limited. Analyses often lack methodological rigor needed to give confidence in the findings or details necessary to be useful for program development and evaluation. Growing access to unit records, both administrative academic records maintained at campuses and wage records submitted by employers under unemployment insurance reporting requirements, opens up the possibility to obtain more reliable and more useful estimates of such effects.

This pilot study was undertaken to gauge the feasibility and potential value of using linked administrative academic-wage record data to assess employment outcomes of work-based applied learning experiences offered within SUNY Works. We conclude that, subject to limitations that presently apply within SUNY, such data can be used to estimate the effects of internships (and, indeed, other forms of applied learning) on employment outcomes.

The pilot study uncovered findings that are useful, some seemingly evident and others suggestive. First, the more important differences in the effects of internships on “immediate” employment outcomes in NYS appear to occur by field of study.

Here, both features of the internship offered and labor market considerations likely come into play. Second, individual attributes of gender, racial/ethnic group, Pell grant eligibility, or SAT score generally show no patterns for the effects of internship on employment outcomes in this limited sample. That finding is generally encouraging, in that the effects of internships on employment outcomes should apply to all students regardless of background.

However, to the extent that formal internship taking within degree programs is associated with more favorable employment outcomes for groups otherwise considered less likely to secure good jobs at good wages (e.g., females, graduates from underrepresented groups, Pell grant recipients), such results might be considered a particularly good result. Differences by attribute do emerge within fields, both favorable and unfavorable, and open up questions about why and how personal attributes may matter with respect to participation in formal internships in particular fields. These findings apply to a limited set of employment outcomes, namely the effects of internship on “immediate” employment outcomes within NYS. Those employed outside NYS, or who take up full-time employment later, are excluded from the analysis. The limitations warrant consideration for the improvement of analyses using linked administrative academic-UI wage record data and for the use and interpretation of findings. The key limitation is that, under the current Memorandum with NYSDOL, SUNY does not have access to unit UI wage records. Analyses are possible with grouped data (and we pursued that approach), although such analyses necessarily constrain the extent of the empirical work that can be carried out.

Three other limitations have to do with coverage, classification, and measurement.

The present study worked with entering cohorts at the participating SUNY campus, tracked through to graduation and into employment. Students with internship experiences who transferred to another college or left higher education were not tracked, and students who transferred into the SUNY college and participated in internships were excluded. Moreover, only those graduates taking up jobs in NYS were picked up in the postgraduation period. Finally, students pursuing graduate studies during the period, but receiving a stipend above the minimum wage threshold, were included in the study. The extent to which these gaps in coverage and challenges in sampling matter in the assessment of employment outcomes is not known.

With respect to classification, administrative academic records permit the identification of internship taking through registration in a formal course under which the internship is organized and credit is granted. We lack information on students who may have participated in internships that are not recognized under a formal course offering. Moreover, administrative academic records lack details on the features or nature of the internship experience. The findings from this study are suggestive in this regard: Programs in Business (and to a lesser extent in Health Science), with generally more favorable effects of internships on employment outcomes, may have in common key features, among which are

(a) established internships as a regular and recognized option in the degree programs;

(b) ongoing relationships with employers who host interns;

(c) strong participation in internships; and

(d) relatively lower rates of postgraduate study. Details confirming these kinds of features are known at the program and campus level, less so at the system level where administrative academic data provide the primary source of information on programs within and across campuses. As noted, efforts to identify features and attributes of internships (and other forms of applied learning) in administrative academic information systems are underway at SUNY campuses. As these efforts proceed, closer attention might be given to particular features for internships that, when analyzed with linked administrative academic-UI wage record data, could be useful for program development and evaluation.

That said, analyses using linked unit record data are most useful when conceived in the light of a campus profile in terms of degree programs and circumstances with regard to student intake and likely graduate destinations. On the former, the selection of fields for analysis in this pilot study was based on close knowledge and advice from officials at the participating campus, as opposed to application of a standard classification of degree programs used by SUNY. Such system-wide classifications can be used to good effect for some purposes. For this pilot study of a single campus, however, campus-level knowledge led to a stronger implementation of the design and, arguably, more useful findings for the programs and campus concerned.

Lacking details on internship or program features, analyses similar to those carried out in the pilot study may still be useful. A great advantage of the linked administrative academic-UI wage record data is that routine data collection allows for relatively easy updating each year or two. Individual programs or campuses can make use of successive years of data on program graduates, distinguished by participation in internship among other individ- ual or program attributes. As changes in internship offerings (e.g., organization of the internship, involvement of faculty or employers) are implemented, employment outcomes can be tracked from before to after such changes. Ongoing monitoring of this type can be made more useful when other details (e.g., recording of internships not taken for credit; other forms of applied learning) are available in the unit records.

Finally, with respect to measurement, the NYS employment outcomes examined in the pilot study reflect two limitations. First, the minimum wage threshold used to screen out part-time em- ployment is likely too low, not least with respect to stipends paid to graduates pursing postgraduate studies. For fields with rela- tively large proportions continuing on to advanced degree work, rates of employment will be higher and average wages lower. when compared to a subset of graduates entering regular, full-time employment. A different (higher) threshold can be used, although the rationale for any threshold derives from a careful delineation of the subgroup of graduates of interest. The second limitation is that the NYS employment outcomes used in this study refer only to the “immediate” postgraduation period (up to six quarters). As suggested in studies of the time-path of earnings byfield, favorable outcomes (here, the effects of internships) may emerge more strongly in five or ten years. In sum, administrative data can be usefully marshalled to study the impact of internships on employment opportunities. Our analysis of employment outcomes shows mixed results due, in part, to data restrictions that limited our analysis to matched “pairs,” rather than matched unit records as in the main report.

And, in part, our results likely reflect differences in the labor markets for graduates in different fields. Ideally, reseachers evaluating the impact of applied-learning experiences, like internships, would have access to unit record data (where available); regional employment and academic data to account for graduates who leave the state; and comprehensive student data (through university, state, or national systems) to account for students who enter a campus as a transfer student or leave a campus to pursue studies elsewhere, including graduate study. They would also account for differences among academic majors of graduates and among the labor markets they are likely to enter. This is an ambitious, but worthwhile, agenda.