October 17, 2017

This year, New York State enacted the County-Wide Shared Services Initiative (CWSSI) law with the mission of reducing property taxes and improving local government efficiency. The law requires counties to convene a shared services panel consisting of the chief executive officer of all towns, villages, and cities, and with the option of including school districts to develop taxpayer savings and efficiencies plans. Counties had the option of submitting a plan by September 15, 2017, or September 15, 2018.

The first round of the CWSSI program has yielded taxpayer savings, efficiencies, and better coordination among local governments across the state. More importantly, the state law created an infrastructure for better coordination and cooperation among local governments.

Here are the central findings:

Important to the process was the “bottom up” approach, i.e., allowing the local municipalities to drive the process and outcomes, instead of counties simply dictating what would be included. As the Montgomery County plan stated, success was because it was the “‘bottom to top’ approach” and the Albany County plan “was driven from the bottom-up” so that “every community was heard.” This was critical for buy in and success.

Some of the additional challenges after our review were: inconsistent reporting, which at times, made it difficult to compare plans. Given the relative newness of the law, this on some level is understandable and likely improved for next year. Additional legal and regulatory barriers made some proposals more difficult or impossible to adopt/implement than others. It would be beneficial to improve these processes in the future.

Many counties took this as a first step, stating they would continue to work beyond the scope of the law. We recommend that this important work therefore continue with the adoption of a permanent shared service panel structure, coupled with technical support and financial incentives provided by the state. We believe those ingredients are recipes for success. If the initial plans are any indication, there could be additional property tax savings and increased government efficiency.

As Mayor Martin P. Flint, Jr. of the village of Remsen said of the Oneida County shared services plan, “This was a great first step in the right direction.”

In January, as part of his State of the State agenda, Governor Andrew M. Cuomo proposed a new program requiring that counties to convene local municipalities to develop and approve plans to lower the cost of local government by finding efficiencies and shared services. A final version of the plan was enacted in the state’s budget (a copy of the law is attached as Appendix A). 1 Known as the County-Wide Shared Services Initiative (CWSSI), every county had to convene a shared services panel to develop a Shared Services and Taxpayer Savings Plan.

The law authorized the chief executive officer of each county, outside of a city of one million or more residents, to prepare a plan for shared services among the county, cities, towns, and villages within the county for the purpose of identifying property tax savings. In New York, the “chief executive” function is different county-by-county, with some being elected executives and some being managers appointed by the county legislature. Each county was mandated to create a Shared Services Panel, chaired by the chief executive officer of the county and comprised of one representative from each city, town, and village within the county. School districts, Boards of Cooperative Educational Services (BOCES), and special improvement districts within the county could also participate, though they were not required to do so. In all, nine counties Albany, Dutchess, Franklin, Nassau, Onondaga, Ontario, St. Lawrence, Suffolk, and Wayne — included school districts/BOCES in the process.

The statute requires that each county’s plan contain “new recurring property tax savings through actions such as, but not limited to, the elimination of duplicative services; shared services such as joint purchasing, shared highway equipment, shared storage facilities, shared plowing services, and energy and insurance purchasing cooperatives; reduction in back office administrative overhead; and better coordination of services.” Moreover, nothing in the process allowed the shared service panels from overwriting local laws and rules. If plans contain proposed actions that by law are otherwise subject to a procedural requirement such as a public referendum, then the actions will not be operative until said procedural requirement occurs.

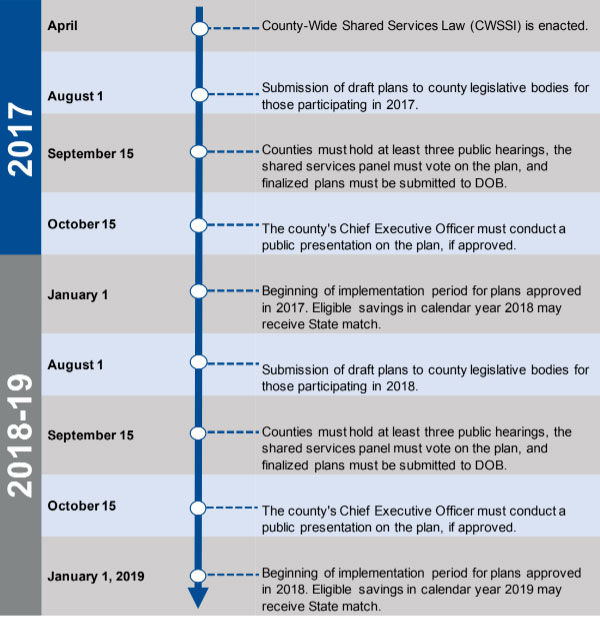

Under the law, counties may elect to defer adoption of a plan until 2018, but must report to the public the reason for the deferral. Thirty-four of the fifty-seven eligible counties submitted adopted proposals to the state this year. Counties deferring until 2018 will follow the same process as outlined for 2017, with the same deadlines. Ahead of the counties convening their respective local municipalities the Department of State held information sessions2 on the program, issued several guidance documents, and provided technical assistance throughout the process.3 In addition, a May 2017 guide by the Campbell Public Affairs Institute at the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs at Syracuse University outlined some of the lessons and best practices that New York State counties should consider when contemplating the possibility of sharing services and hosting public forums to discuss shared service plans. (For a full description of the Maxwell School Best Practices see Appendix D.)

The county chief executive officer was to consult with panel members and collective bargaining units in creating a draft plan. Counties were required to submit their draft property tax savings plan to their respective county legislative body no later than August 1, 2017. Each plan was to be accompanied by certification from the county chief executive as to the accuracy of the savings contained. The county legislative bodies reviewed the draft plans and could, by a majority of its members, issue an advisory report with recommendations to the county chief executive officer. If necessary, the county chief executive officer could modify the shared services plan in response to the advisory report. Each county was required to hold at least three public hearings, prior to a vote by the Shared Services Panel to approve the plan, to allow for public input on the proposed plan (for a listing of the public hearings, see Appendix G). Public notice of hearings was to be provided at least one week prior to the hearing, as prescribed in subdivision 1 of section 104 of the Public Officers Law.

Shared Services Panels that did not defer until 2018 were required to hold a vote on the final plan by September 15, 2017. Prior to the vote, each member of the Panel could have removed any action that affects their local government. Each Panel member had to state in writing the reason for their vote; a majority of the Panel had to approve the plan in order for it to be adopted. After adoption, the county chief executive officer submitted the final plan to the New York State Division of the Budget and disseminated it to county residents. Approved shared services plans had to be presented publicly no later than October 15, 2017. The law states that if the plan was not approved, the county chief executive officer had to release the draft plan to the public as well as the vote and justification of each panel member. To date, no panels have voted down a plan.

Under the CWSSI law, there is a one-time financial match from the savings in the first year of each county’s adopted plan. Thus, each county with a Shared Services Plan that is finalized in 2017 would be eligible for a one-time match from the state of the net savings from the new shared service actions that are implemented and achieved among multiple jurisdictions between January 1 and December 31 of 2018. Counties that finalize Shared Services Plans in 2018 will be eligible for a one-time state match for savings achieved between January 1 and December 31 of 2019. The Department of State will develop an application for counties to apply for state funds to match the net savings achieved from each new Shared Services Plan action implemented in the aforementioned timeline. Only actually and demonstrably realized net savings, rather than expected savings from Shared Services Plans, are eligible for the match.

As described by the New York State Division of Budget’s Briefing Book, the policy and legislative intent behind the CWSSI was “to help reduce the burden of high property taxes” 4 as well to find more efficient delivery of services and programs. Below, we briefly examine the rationale behind the law.

The logic behind having counties convene the process at the local level was three-fold: (1) every resident in New York lives in a county, but not necessarily a village or a city, for instance; (2) counties are, in many ways, the most regional5 form of local government; and, (3) because other local units of municipal governments — towns villages, and cities — with few exceptions, are wholly contained within the boundaries of counties. However, though more regional in size and scope, the size of a county can vary greatly (e.g., Hamilton County has a population under 5,000 — smaller than many other towns and villages).

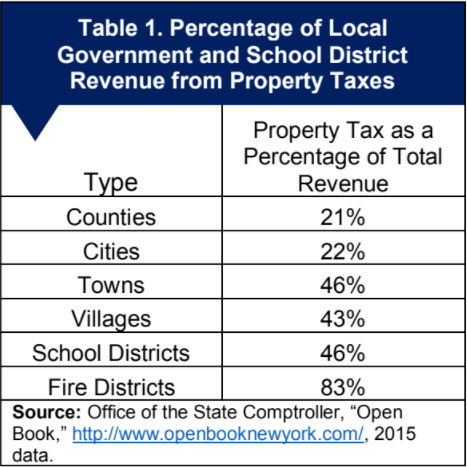

Property taxes were first imposed in New York in 1654 when it was a Dutch Colony, New Amsterdam. Today, property taxes help fund local government and school programs and services. Counties, towns, villages, cities, fire districts, and other special taxing districts (e.g., certain library districts — subject to voter approval) have independent power to levy property taxes.

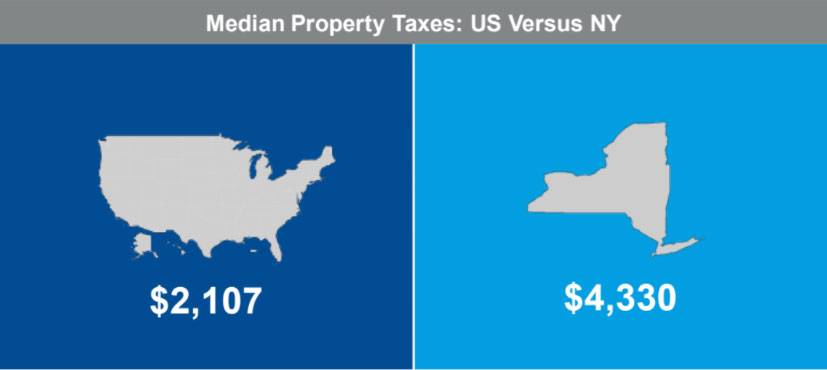

The local property tax remains one of the most significant tax burdens in New York State. Counties in New York have among the highest property taxes in the nation. The median property tax burden in New York ($4,330) is more than twice the national median. In 2003, the total property tax levies for counties, towns, villages, cities, school districts and fire districts was $24.6 billion. By 2015, total property tax levies rose to $42.8 billion — or 74 percent. New York ranks fourth overall among all states in median local property taxes paid.

However, if broken down to the county level, Westchester County has the highest property taxes in the nation — more than four times higher than the national median — and five of the fifteen counties with the highest property taxes in the nation are in New York. The other counties in the top fifteen (Nassau, Rockland, Putnam, and Suffolk) are located downstate. However, when you measure in property taxes as a percentage of home value, upstate counties have among the highest property taxes in the nation.

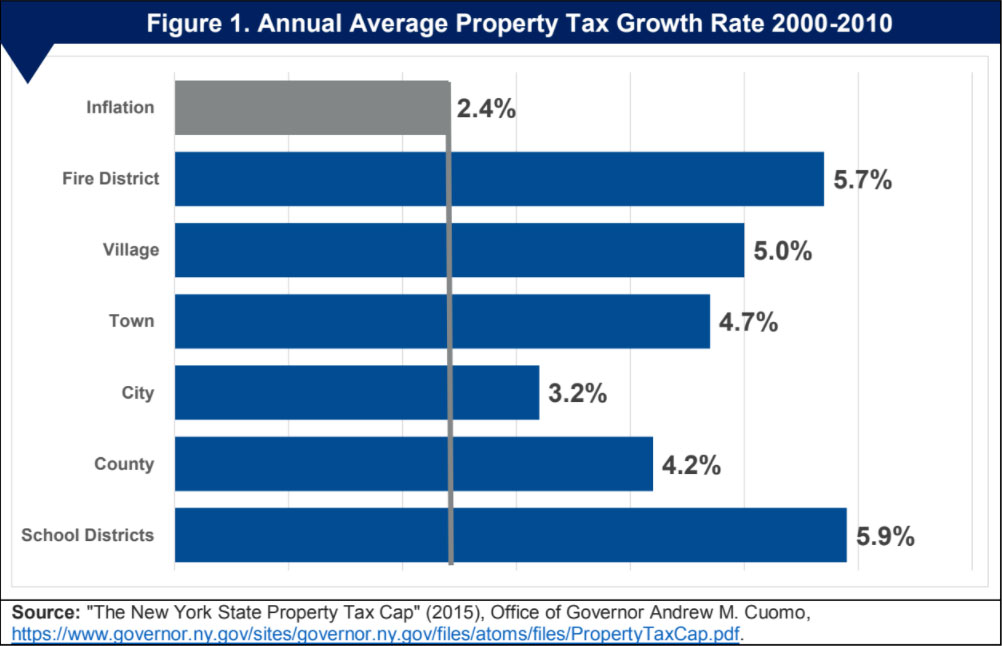

Until the state enacted the inflationary real property tax cap with a maximum annual increase of two percent, 8 annual property tax increases in counties, towns, villages, cities, school districts, and fire districts exceeded inflation — at more than twice the rate. School districts (with fire districts a close second) have the highest annual property tax increases and cities the smallest increase (see Figure 1). School districts make up approximately 72 percent of an average homeowner’s total property tax bill with counties accounting for 12 percent, towns 9 percent, cities 2 percent, villages 3 percent, and fire districts 2 percent. Therefore, a central reason behind the state law was reducing property taxes.

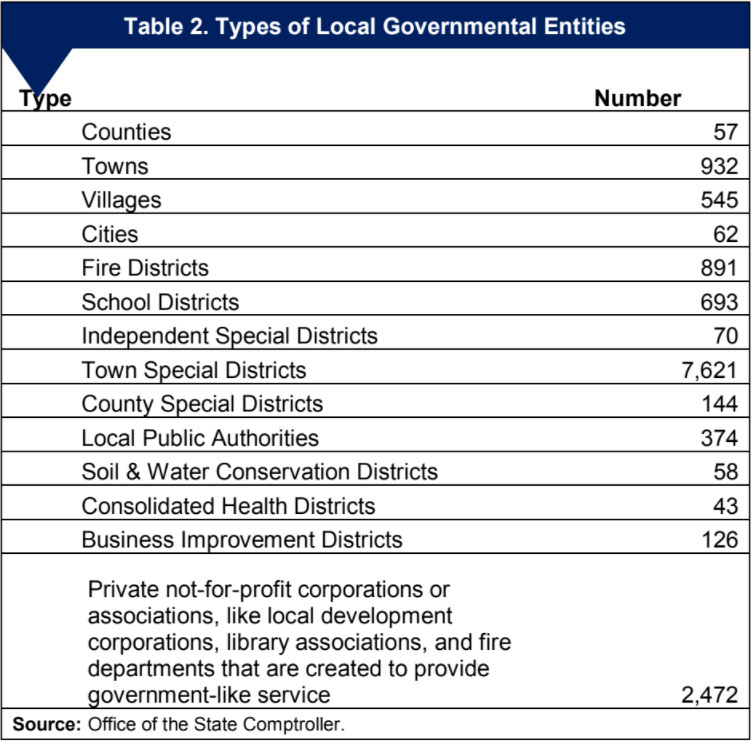

To address the state’s property tax burden, the CWSSI’s intent was to try to improve local government efficiency. We note that many of the plans included detailed histories of past shared services. Indeed, local governments play a critical role in delivering services in communities. However, the system of local governments and other entities is complex — not only for average citizens, but public officials alike. In many ways, it’s not a coherent system; it is a series of patchwork entities that were created to meet certain needs over time, which in turn has grown increasingly cumbersome There are thousands of different types of local governmental entities, with varying degree of autonomy, taxing and debt issuing authority, and with overlapping jurisdiction.

There are thousands of local entities9 with taxing authority including, but not limited to: 693 school districts, 932 towns, 545 villages, sixty-two cities, fifty-seven counties, 891 fire districts, and about seventy independent special districts. Layered on top of these independent taxing authorities are thousands of other local entities that do not have independent real property taxing authority, but in many cases, have the power to assess other fees or issue debt such as 7,621 town special districts, 144 county special districts, 374 local public authorities, fifty-eight soil and water conservation districts, forty-three consolidated health districts, and 126 business improvement districts. Finally, there are 2,472 private not-for-profit corporations or associations, like local development corporations, library associations, and fire departments that are created to provide government-like service. Although they have no independent taxing authority, many can issue bonds and the like.

Some local governments are also experiencing fiscal distress. Legislation enacted in 2013 created the Financial Restructuring Board for Local Governments to help struggling municipalities restructure their finances. To date, the Restructuring Board is currently reviewing or has completed reviews for twenty municipalities, and the CWSSI is an additional tool to assist these municipalities to get on stronger financial footing.

While the state has argued that inefficiencies and duplication drives increased local costs, some counties responded in their plans, that increased costs are driven by federal and state mandates. Chenango, Dutchess, Erie, Franklin, Fulton, Madison, Monroe, Oneida, Onondaga, Ontario, Oswego, Westchester, and Yates noted that increasing property tax costs are also a result of unfunded mandates from the state, including the Taylor Law and Triborough Amendment; Wicks Law; the Medicaid funding framework that split costs with counties (which the state has noted it has taken over 100 percent of any additional costs to counties); the absence of a strong “ability to pay” criterion in binding arbitration; and the costly civil service provisions, including 207a and 207c of the General Municipal Law regarding firefighter and police officer disability benefits.

In all, out of the fifty-seven applicable counties, thirty-four (or nearly 60 percent) submitted adopted plans to the state. In addition, several of the counties that deferred final action until next year, including Chemung, Orange, and Tioga, submitted draft plans to the state. We reviewed all thirty-four plans that were approved and submitted, as well as the material submitted by the remaining counties that deferred until 2018.

There was wide variation among the counties in how they presented their plans and how detailed the methodologies were in determining their savings. With greater resources to bear, the assumption was that larger counties would be more complete and sophisticated in their underlying analysis. That wasn’t always the case. In many cases, the smaller counties provided more detailed information behind their estimates and assumptions. For example, Cattaraugus and Schuyler Counties provided significant detail to back up their savings estimates and assumptions, while Suffolk County did not provide as much detail. Franklin County’s plan was not in-depth and was not long at two pages, but it provided considerable detail on how they arrived at their savings by clearly stating their assumptions. Nassau County provided a tremendous amount of detail, but the data was not well organized or presented in an easy-to-understand or synthesized fashion.

Some counties provided virtually no detail on how they arrived at their savings estimates. For example, Columbia County provided virtually no details in their one-page plan; Broome, provided newspaper articles summarizing their process, but virtually no backup of their savings methodologies; Clinton County submitted a one-and-a-half page spreadsheet with little detail; Livingston County provided a spreadsheet with each proposal broken down by savings, but without any methodology of how they arrived at their savings; Dutchess, Monroe, Ulster, and Westchester Counties had more detailed sheets breaking down the cost for each proposal, but with very little detail on their methodologies and assumptions; Saratoga provided a short summary of their two proposals; and Wyoming County had a high-level one-page spreadsheet.

On the other hand, Albany, Chautauqua, Onondaga, Oneida, Ontario, Rensselaer, Schenectady, and Schuyler Counties provided detailed summaries of how they arrived at their savings for each proposal, including detailed methodologies.

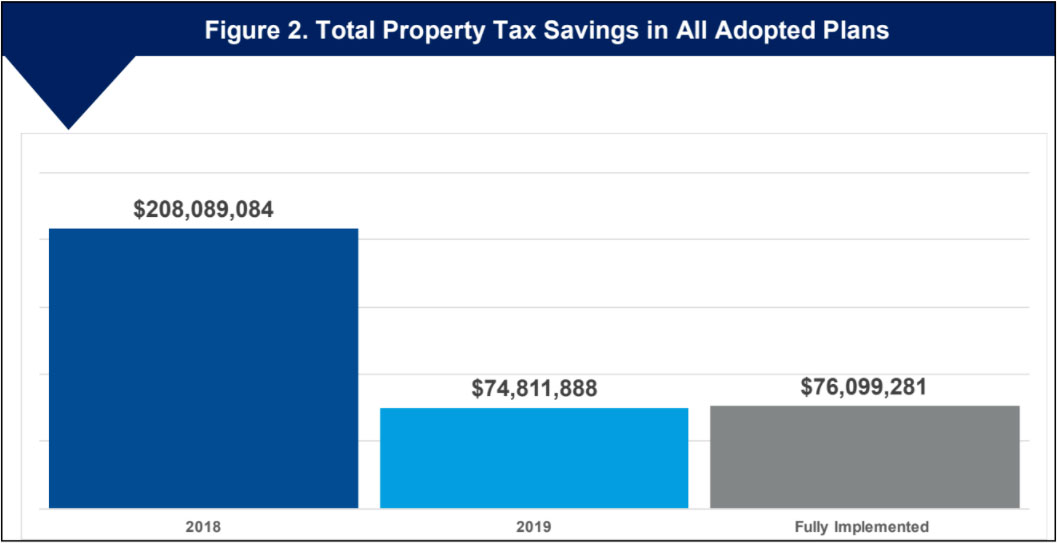

The law required counties submit net savings anticipated in calendar year 2018, calendar year 2019, and annually thereafter.

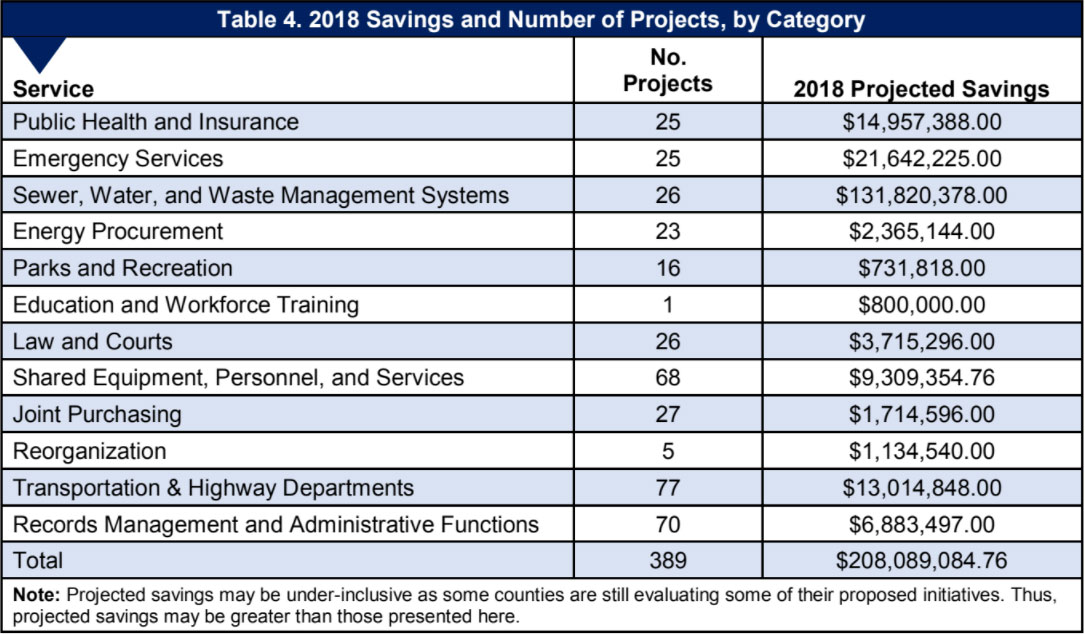

In total, counties submitted 389 proposals adopted resulting in $208 million in projected savings in 2018, $75 million in 2019, and $76.1 million in recurring savings thereafter. The Rockefeller Institute of Government computed its own project counts and 2018 savings values for each project based on its own review of individual reports. Specifically, the Institute used coversheets submitted by the counties — in addition to project descriptions found in the more detailed reports — as the basis for the project count and total 2018 savings. Moreover, the Rockefeller Institute of Government did additional research based on media reports and inference about which projects were withdrawn (but not clearly marked as such in the reports). Taken together, likely accounts for some of the initial slight differences in totals reported elsewhere.

When ranking counties by highest tax savings reported in the first year (2018), Nassau County is first ($130.5 million) followed by Broome County ($20.3 million), Suffolk County ($16.5 million), Dutchess County ($15.2 million), and Monroe County ($7.3 million). If you ranked counties by reported recurring tax savings in the out-years, the top five are Suffolk ($20.9 million), Dutchess ($12.5 million), Albany ($9.7 million), Montgomery ($4.6 million), and Erie ($4.2 million).11 A chart summarizing the totals by county can be found at Appendix C.

As was mentioned above, the CWSSI law required that the sum total of net savings in such plan must be certified as being anticipated in calendar year 2018, calendar year 2019, and annually thereafter. However, seven of the thirty-four counties that adopted plans this year failed to properly report this financial information. Those counties were Broome, Columbia, Livingston, Nassau, St. Lawrence, Wayne, and Wyoming counties. In every case these counties submitted at least 2018 savings, but did not submit the required 2019 and fully implemented projections. Given that some of the counties did not provided the legally required fiscal information the $76.1 million total recurring savings in the out-years is incomplete, and likely higher.

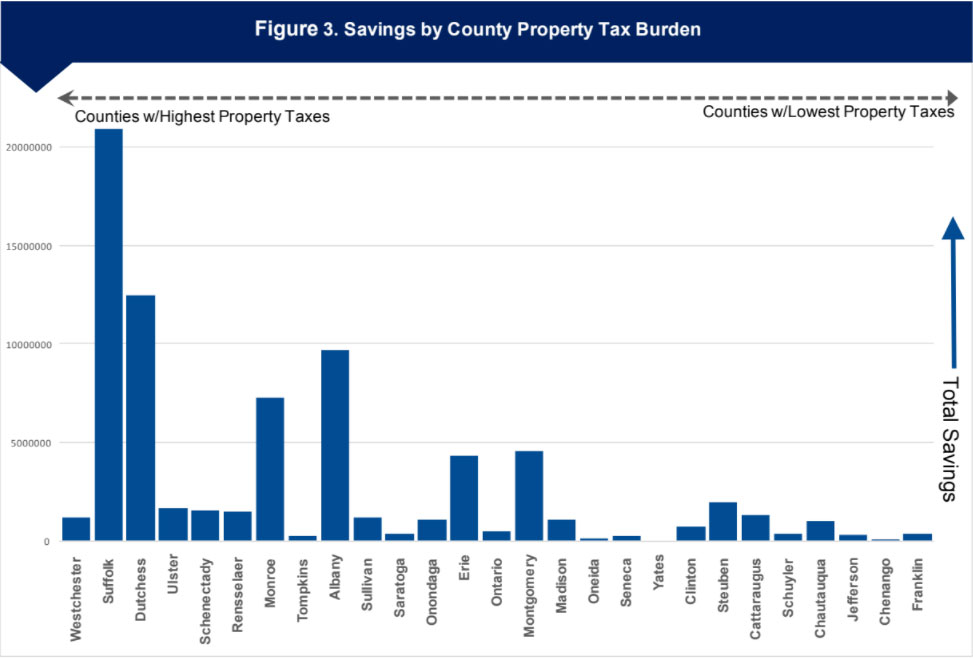

We also reviewed the county recurring property tax savings in relation to their size and overall property tax burden. One could assume that the counties with the larger populations would have the larger total savings in total dollars. In some cases, that was true. The most populated counties — including Suffolk, Monroe, Erie, Dutchess, and Albany — submitted more total recurring savings to the state. (See Appendix H for a full breakdown of tax savings by population.) However, quite a different picture emerged in other cases. When breaking down the savings compared to the size and property tax burden of the counties, there is significant variation among them.

For instance, of the four largest counties (populations of 500,000 or more), Westchester County found the least reported recurring tax savings ($1.2 million), while Suffolk County found significantly more tax savings than Westchester ($20.9 million). Additionally, the remaining highest populated counties, Monroe and Erie, found more overall tax savings than Westchester.

In other cases, much smaller counties reported larger overall tax savings than some of the state’s largest counties. Montgomery County stands out in this case. Montgomery County, with a population of less than 50,000 people, identified $4.6 million in recurring tax savings versus Westchester County with nearly one million people which found $1.2 million in savings. In fact, Montgomery County had greater property tax savings than several other much larger counties, including Erie, Onondaga, Saratoga, and Oneida counties.

Finally, other smaller counties outperformed some of the largest counties in the state. Dutchess ($12.5 million) and Albany ($9.7 million) counties with populations of approximately 300,000 each, found greater savings than Erie County ($4.2 million), which is three times the size of Dutchess and Albany, as well as Monroe County ($7.3 millions), which has nearly 750,000 people.

An interesting picture emerges when you compare a county’s overall recurring property tax savings with overall property tax burden. Counties with higher total property tax burdens did not necessarily find more recurring tax savings. Figure 3 shows the overall tax savings by county in order of overall property tax burden. For example, Westchester County has the highest property tax burden in the state — and the nation — and found less recurring tax savings than eleven counties with lower property taxes. Suffolk County, on the other hand, has the fifth highest property tax burden in the state, but it exceeds every other counties’ total reported recurring tax savings. Counties such as Albany, Erie, and Montgomery that fall in the relative middle in overall property tax burden in the state, exceed the recurring savings of several other counties with higher property taxes such as Tompkins, Rensselaer, Schenectady, and Ulster.

Using data reported by the counties, an average per taxpayer savings averages to roughly $46 per taxpayer annually when all plans are fully implemented. However, given the reporting issues with counties, it is unclear how accurate the per-taxpayer savings are at this time.

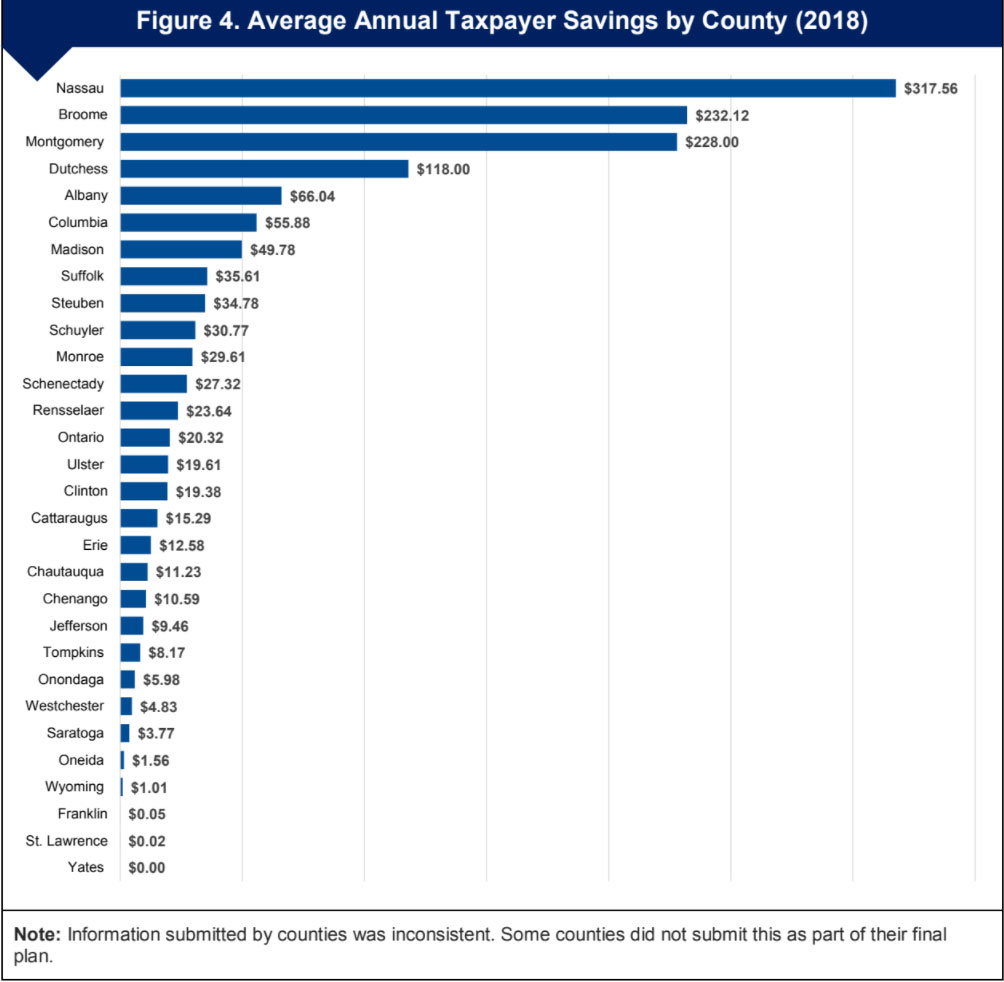

As Figure 4 shows, Nassau, Broome, Montgomery, Dutchess, and Albany Counties reported the largest savings per taxpayer for 2018, while Oneida, Wyoming, Franklin, St. Lawrence, and Yates Counties are at the bottom. Nassau County was highest at $317.56 and the lowest was St. Lawrence County at $0.02 per taxpayer. (We eliminated Yates, given they did not submit any proposals in their plan.)

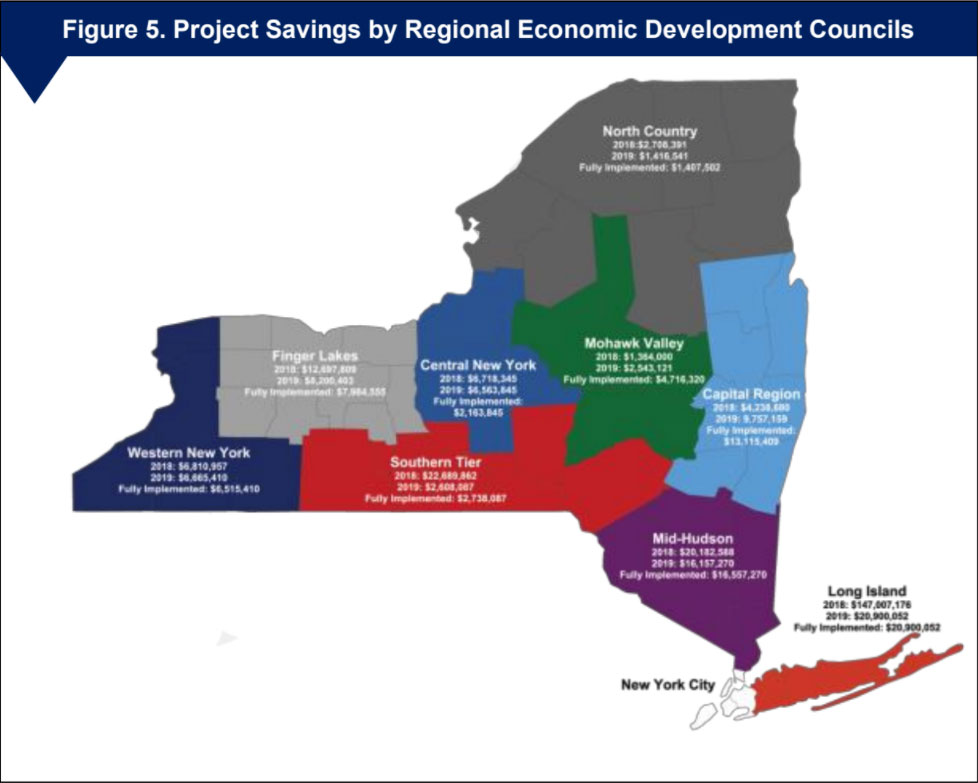

When looking at the overall fully phased in savings and projects by Regional Economic Development Council regions, Long Island had the most savings, with the Mid-Hudson Valley coming in a close second. The North Country trailed, with less than $1.5 million fully phased in. In terms of total projects, the Finger Lakes and Hudson Valley regions had the most (sixty-four), while North Country had the least (nineteen).

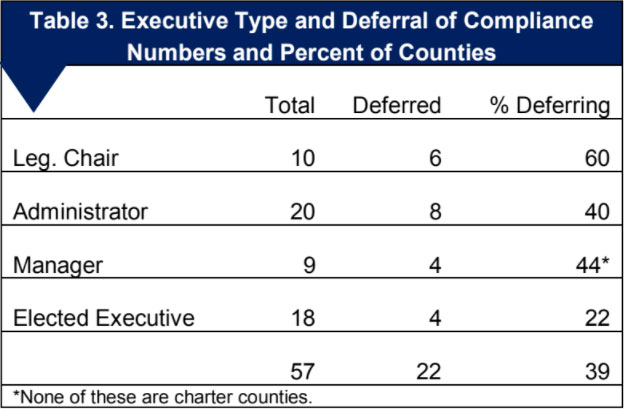

In general, jurisdictions with the legally strongest, most politically independent, locally grounded executives were least likely to defer their adoption of their shared services plans in the first year. In fact, as Table 3 illustrates, counties with elected executives deferred the adoption of their plans about half the time that appointed county managers did.

New York State has sixty-two counties. Five are within greater New York City, and do not function independently as general purpose governments (the boroughs of New York City). The remaining fifty-seven are among the state’s general purpose local governments that are constitutionally required to have “… a legislative body elected by the people thereof….”

Thirty-four of these are organized and function under the State’s County and Alternative County Government laws, which initially vests governing authority in either a board comprised of the supervisors of the county’s constituent towns or a separately elected legislature.

The remaining twenty-three counties have adopted home rule charters under the provisions of Article IX of the state constitution which provides that “Counties, other than those wholly included within a city, shall be empowered by general law, or by special law enacted upon county request … to adopt, amend or repeal alternative forms of county government provided by the legislature or to prepare, adopt, amend or repeal alternative forms of their own.

In 2017 there were sixteen counties operating with boards of supervisors and forty-two — twenty-three with charters and eighteen others — with legislatures. Boards of Supervisors are the traditional governing structure for counties in New York State. Legislature systems in counties were created in response to United States Supreme Court’s one-person-one-vote decisions of the mid-1960s. Board of Supervisor systems in counties that retained them were able to achieve compliance with one-person-one-vote by adopting weighted voting schemes.

Though most have separate executives, there is no state constitutional requirement that county governments in New York State have a separation of powers system. In seven counties with Boards of Supervisors and three with legislatures executive duties are performed by the body’s presiding officer, elected by his or her peers. A county operating under state law may choose to adopt one of four specified alternative forms of government with varying degrees of independent executive authority. Counties may appoint: an administrator (who may also be the board chair) to serve conterminously with the elected board; a director to serve a fixed four-year term; or a manager — uniquely given authority to appoint and remove other department heads — to serve at its pleasure. Or a county may choose to have a president elected to a four-year term, with veto power.15 If one of these options are chosen, executive powers and responsibilities are specified in state law.

Currently, seven counties operating wit Boards of Supervisors have administrators, and two employ managers. Three of the counties with legislatures and operating under state law assign executive duties to the legislative chair, four have managers, and eleven employ administrators. The director and president options for counties are not currently in use.

Of the twenty-three charter counties, eighteen have chosen a separation of powers system with an elected executive. These tend to be the state’s largest counties in population and size of budget. Three have managers, and two administrators. The powers and duties of these executives are locally determined; they are based in the county charter, not state law.

Twenty-two counties deferred compliance with the 2017 state shared services planning requirement. Of these, six (or 37.5 percent with this form of government) were governed through Boards of Supervisors. Half of these Board of Supervisor counties had no separate executive, two had administrators and one had a manager. Of the remaining sixteen counties that deferred, six had administrators, four had elected executives, three had managers and three had no separation of powers in their governments. Additionally, none of the three with manager systems was a charter county.

Many plans that were submitted illustrated that they built on past work. In addition to real property tax savings, finding more efficiencies in government were also a central element to the plans. Initiatives were classified based on the type of services performed. A cursory analysis of each county’s shared services report finds that CWSSI participants produced a range of programs in twelve main areas. Those areas are: public health and insurance; emergency services; sewer, water, and waste management systems; energy procurement; parks and recreation; education and workforce training; law and courts; shared equipment, personnel, and services; joint purchasing; government reorganization; transportation and highway departments; and, records management and administrative functions. Table 4 includes the total number of projects and 2018 savings by type of service.

The Institute only used 2018 data when breaking down by project in this section because it was the most complete.

Pooling health insurance costs is an area that could result in significant savings to municipalities. Several counties, including Albany, Broome, Monroe, Saratoga, Schenectady, and Tompkins, are developing health consortia designed to improve the quality of health care and reduce costs — finding at least $10.8 million in savings. Under existing law, small municipalities are often prohibited from adopting a self-insured plan because “the small number of health contracts and the potential volatility of a small pool of contracts present too much risk” (Schenectady County County-Wide Shared Services Property Tax Savings Plan). However, by aggregating municipalities into one self-insured consortium, smaller municipalities are able to participate and achieve greater savings.

In Schenectady County, for example, local officials engaged health care consultants from Locey and Cahill, LLC, to evaluate alternative models under Articles 44 (Employee Welfare Funds) and 47 (Municipal Cooperative Health Benefit Plans) of the New York State Insurance Law. Following an analysis of demographic and health cost claims data, health care plans, labor contract language, and premium equivalent rates, Locey and Cahill, LLC, identified approximately $766,000 in initial savings. Under the consortium model, the county predicts that the majority of savings will “accrue to the Pooling health insurance costs is an area that could result in significant savings to municipalities. Several counties, including Albany, Broome, Monroe, Saratoga, Schenectady, and Tompkins, are developing health consortia designed to improve the quality of health care and reduce costs — finding at least $10.8 million in savings.

Under existing law, small municipalities are often prohibited from adopting a self-insured plan because “the small number of health contracts and the potential volatility of a small pool of contracts present too much risk” (Schenectady County County-Wide Shared Services Property Tax Savings Plan). However, by aggregating municipalities into one self-insured consortium, smaller municipalities are able to participate and achieve greater savings.

In Schenectady County, for example, local officials engaged health care consultants from Locey and Cahill, LLC, to evaluate alternative models under Articles 44 (Employee Welfare Funds) and 47 (Municipal Cooperative Health Benefit Plans) of the New York State Insurance Law. Following an analysis of demographic and health cost claims data, health care plans, labor contract language, and premium equivalent rates, Locey and Cahill, LLC, identified approximately $766,000 in initial savings. Under the consortium model, the county predicts that the majority of savings will “accrue to the smaller municipalities that cannot independently capitalize on the savings of a self-insured plan.”

In addition to developing health care consortia, several others are considering participation in pharmaceutical prescription programs. In Albany County, for example, local officials are considering joining the Capital District BOCES Pharmacy Purchasing Coalition, which would allow schools to collectively purchase pharmacy benefits without sacrificing existing coverage. Similar pharmaceutical coalitions that seek to leverage large-scale group purchasing discounts are under consideration in Broome and Franklin Counties, as well. Other counties committed to pursuing health insurance coalitions/consortia in the future such as Ontario and Rensselaer counties.

In just over ten counties, local officials proposed to consolidate emergency communications, fire and ambulance services, and dispatch operations for a total of $21.6 million in 2018 projected savings. While in some instances, the county will assume responsibility for dispatch services and emergency communication systems, others seek to shrink costs and generate savings through shared personnel and equipment. With respect to the former, Sullivan County 911 has agreed to provide police dispatching services to the town of Fallsburg. With a population of 12,870, the town has struggled to meet growing demands for policing without raising taxes. However, by empowering Sullivan County 911 to take over its police dispatching services, the town will be able to add up to five additional police officer positions, or one additional officer per shift (Sullivan County Shared Services Final Plan and Report).

By comparison, Chautauqua County plans to offset the administrative burden placed on individual fire companies by hiring a full-time administrator (County-Wide Shared Service Property Tax Savings Plan for Chautauqua County). As the ranks of volunteer firefighters continue to dwindle, the county believes that a shared staff person will reduce the growing paperwork burden imposed on fire chiefs and extend the availability and activity of existing volunteers. In order to identify current and future needs for support, Chautauqua County will conduct a thorough evaluation of existing operations under the direction of local fire service leaders. Undoubtedly, their participation in the Countywide Fire Services Initiative will result in greater buy in.

In 2018, the greatest level of projected savings was reported in sewer, water, and waste management service. However, nearly all projected savings in this area are contingent on a single initiative, namely the $128 million plan to consolidate sewage treatment services in the city of Long Beach with Nassau County. If the plan is successful, the city’s wastewater will be transported through an aqueduct under Sunrise Highway to Bay Park Water Reclamation Facility, where Nassau County is currently installing advanced denitrification technology. Once treated, the city’s wastewater will be transported to the Cedar Creek Wastewater Treatment Plant and pumped into the Atlantic Ocean. In June 2017, city officials told the Long Island Herald that the project would prevent more than fifteen tons of pollutants from being deposited into Reynolds Channel and the Western Bays.

The remaining initiatives in this area are far more modest in size and scope. In Schuyler County, for example, the villages of Watkins Glen and Montour Falls hope to achieve cost savings by developing a joint wastewater treatment plant. In addition to decommissioning existing plants and building a new state-of-the-art facility, both villages plan to create a regional governing structure comprised of all municipal users. Cost savings of $200,000 will be achieved primarily by reducing staffing levels. However, the county anticipates that, by decommissioning existing sites, two additional waterfront locations will become available for future development. In addition to shared facilities, counties such Chautauqua plan to address staffing problems by developing a shared pool of water and wastewater system operators.

While smaller municipalities are generally forced to rely on a single operator who is almost “always on call,” larger systems attempt to meet staffing shortages with costly overtime pay. By combining staff from as many as twelve municipalities, several of which are located in neighboring Cattaraugus County, the Chautauqua Region Water & Wastewater Cooperative aims to reduce staffing costs by as much as 20 percent (or $317,000 annually), while improving the overall quality of service.

Finally, other municipalities plan to share responsibility for water and sewer line construction. In the town of Dickinson, for example, SUNY Broome and Broome County signed a three-way agreement to install a new waterline on the SUNY Broome campus. The town of Dickinson will perform the work, which will result in a savings of $64,000 to the county.

Many counties, like Albany, Clinton, Monroe, and Schenectady adopted proposals to pool energy costs and implement energy efficiency program. Several counties are already participating in the Municipal Electric and Gas Alliance (MEGA) — a multicounty/municipality energy purchasing consortium. In Albany and Monroe Counties, participation in Choice Aggregation programs will allow local governments to achieve the most competitive prices for electricity by encouraging municipalities to collectively purchase energy products and services. In Albany, each municipality must pass a local law to participate. However, residents and businesses may opt out of the program at any time. An initial savings of $1,000,000 is expected in Albany County in 2019. Other counties considering participation in the Municipal Electric and Gas Alliance are Cattaraugus, Clinton, Schenectady, and Sullivan.

As many as five counties are considering the possibility of converting conventional street lighting to LED lights, which use approximately 75 percent less energy than traditional incandescent lights. Although the cost to taxpayers for street lighting has compelled local officials to consider alternatives, counties have responded in a multitude of ways. In Albany, for example, the county plans to address local concerns about the specialized maintenance of lights, overall capital costs, and negative encounters with utility companies by centralizing installation services and developing a team of shared maintenance personnel for those municipalities and school districts that need assistance with upkeep. By comparison, Rensselaer teamed up with Siemens Corporation, one of the world’s largest producers of energy-efficient technologies, “to provide the County with an evaluation of energy savings for street lights, to work with National Grid to coordinate buyout of existing street lights and to provide a turnkey solution to migrate existing street lights to LED.” Still other counties have expanded these initiatives beyond street lighting to include municipal buildings. In Schenectady, for example, the establishment of a Municipal Lighting Fund seeks to incentivize installation of LED fixtures through a $125,000 co-fund. To access the fund, municipalities will be required to take advantage of other rebate programs, including those offered by National Grid. However, the county will continue to identify and apply for grant funding. Based on the fund’s current size, Schenectady estimates over $54,000 in annual savings.

Seven counties proposed more than fifteen different initiatives designed to cut back on the costs of maintaining recreational facilities including parks, sports fields, and outdoor movie theaters. As just one example, the village of East Aurora in Erie County has agreed to allow the town of Aurora to utilize a number of village-owned facilities for its summer recreational program, including a general-purpose building, restrooms, tennis courts, and sports fields. In return, the town has promised to provide maintenance services for the facilities while in use. Whereas this arrangement will save East Aurora approximately $8,000 in annual maintenance fees, not having to rent such facilities will save the town of Aurora nearly $18,000 per season. In a similar vein, Broome and Onondaga Counties plan to merge resources and consolidate personnel by offering mowing and landscaping services to several municipalities. Also of note is Onondaga’s proposed web-based data center, which would provide park facility reservations and rental information for every park located in Onondaga County regardless of municipality jurisdiction.

A few initiatives focused on education and workforce training initiatives. One notable example is Montgomery County’s DSS (Department of Social Services) to Work Initiative. Under this initiative, local officials partnered with Fulton Montgomery Community College to develop Job Readiness Skills Training, “a four-week workshop that … mentors participants towards creating positive attitudes and workplace behaviors they need to begin and change their lives.” Beginning in 2018, Montgomery County DSS plans to expand working relationships to include several local school and Hamilton-Fulton-Montgomery BOCES, “drawing upon resources available through the Summer Youth Employment Program and the extraordinarily innovative Agricultural PTECH (Pathway to Technology) program.”

Reorganizing and consolidating courts was included in many plans. Nearly twenty-six initiatives, totaling a projected savings of $3.7 million in 2018, fall under the heading of law and courts. Shared services in this area generally take on one of three forms:

Other counties, such as Cattaraugus, did not include a formal proposal, but would explore court consolidation in the future.

Virtually every county proposed sharing specialty equipment, services and personnel among local governments and school districts. While many informal agreements were already in place, several counties plan to formalize these arrangements through signing a memorandum of understanding. Some of the most common cites for shared services include the following:

Seventeen of the thirty-four participating counties also proposed joint purchasing agreements for materials, parts, and services, sometimes through the county, or among the various municipalities. As just one example, Albany County will create a centralized purchasing system, available to all municipalities, for such items and services as medical supplies, software, computer hardware, equipment, telecommunication systems, gasoline, diesel fuel, waste removal, recycling, electrical, plumbing, heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC), and asbestos removal.

Local municipalities in at least four counties are exploring the possibility of consolidation and dissolution. According to a summary of Article 17-A of the general Municipal Law, “[t]he consolidation of local government entities can result either in the elimination of the original local governments and the forming of a new local governmental entity or in one surviving governmental entity with the others absorbed into it.” By comparison, “dissolution is the termination of a local government entity” (note Article 17-A does not apply to agency consolidations within municipalities). In Chautauqua County, municipal officials are considering both options. Thus, local leaders of the towns of Gerry and Charlotte are seeking a merger with the understanding that the largest source of savings will stem from cost reductions in the highway departments. Indeed, the combined highway crews will be less likely to contract for services from outside agencies; the combined department will purchase less capital equipment; and the cost of administrative functions is also likely to decline (County-wide Shared Service Property Tax Savings Plan: Chautauqua County). By comparison, the village of Cherry Creek is seeking dissolution into the larger town. Spurred by a petition from residents under Article 17-A, negotiations led to a dissolution plan that currently enjoys support from the town board. However, because the town has already assumed many local services, dissolution is expected to result in relatively minor savings. Similar initiatives are under study in the village of Cattaraugus in Cattaraugus County and the village of Cazenovia in Madison County.

Overall, participating counties proposed the greatest number of projects in the areas of transportation and highway departments. By and large, a significant number of these counties and their corresponding municipalities aim to share materials, parts and services that are necessary to the safe and efficient operations of their Public Works Departments. This may include county-wide purchase of salt, sand, asphalt zippers, excavators, and other public works equipment. In Cattaraugus, as in many other places, “[t]he County’s buying power allows it to obtain discounted prices on products and services due to volume and competition among its many vendors. Municipalities are able to piggyback on material bids or purchase items from the County at costs,” (Cattaraugus County Shared Services Plan). Aside from joint purchasing agreements, nearly half of the participating counties expressed interest in equipment sharing, plowing, street sweeping, snow removal, or repaving services. While the full list of services is too long to reproduce here, some notable examples include the following:

Second only to the total number of transportation and highway initiatives, county and municipal government officials identified nearly seventy opportunities to share administrative and “back office” functions. As the Office of the New York State Comptroller has observed, “business office functions appear to hold promise because there is both the potential for savings and they are often easier to implement.” One way to think about shared service opportunities in this area is to group them by subcategories.

In our review of the Shared Services Plans submitted by counties to the Division of Budget and Department of State, including draft plans that were not formally adopted, a number of barriers to sharing services between municipalities and school districts were identified. These include:

This was identified as a problem by Albany, Cattaraugus, Chenango, Columbia, Erie, Madison, Oswego, and Schenectady counties. Currently, municipalities in New York State have three primary options for health care. They can:

According to the Cattaraugus County Shared Services plan, approximately thirty counties are self-funded for health insurance. Similar situations occur in school districts, generally coordinated by the local BOCES. Self-funded plans often purchase stop loss insurance to protect themselves against catastrophic illnesses and accident claims. These self-funded plans are not subject to NYS Department of Financial Services oversight or federal Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA) regulations.

By state law and/or regulation, local governments with fewer than fifty covered employees (the number increases to 100 if starting after 2016), must be community rated. Only employers with more than fifty covered employees (the number has increased to more than 100 employees starting after 2016) can be experience rated, based on recent claims. Further, municipalities that have fewer than 100 employees cannot buy stop loss insurance. These limits imposed by state law and/or regulation effectively limit the availability of municipal health insurance plans and have the effect of driving municipal health insurance costs higher, particularly for smaller local governments.

When two or more municipalities come together for the purpose of providing employee health insurance, they are subject to either Article 47 or Article 44 of the NYS Insurance Law. The process for achieving Article 47 compliance, for self-insured programs, is both time consuming and costly. Only Tompkins County has been able to

achieve compliance, and yet this process took more than three years to complete with the liabilities fully funded. Some of the challenges the Greater Tompkins County Municipal Health Insurance Consortium faced included the governance structure with labor representation, funding of reserving requirements in advance of the effective date (a significant financial burden for municipalities, especially smaller municipalities); filing of plan documents (insurance certificates); development of budget and premium rate models; and a number of other items that the New York State Department of Financial Services required.

A summary of the impacts of Article 47 of the NYS Insurance Law upon cooperative insurance purchasing is delineated in a document entitled “Cooperative Health insurance Purchasing: Article 47 Impediments,” which was provided in the Cattaraugus County Shared Services Plan. Effectively, the requirements of Article 47 compliance upon a self-insured program significantly impact cost effectiveness.

According to the consultant reports cited in the Albany and Schenectady County Shared Services Plans, the process of forming and operating a consortium under Article 44 of the NYS Insurance Law is less onerous than under Article 47 with less reporting and filing requirements. Medical benefits can be provided through an “employee welfare fund”. For these purposes, an employee welfare fund is a trust fund maintained by one of more employers with one or more labor unions, directly or indirectly through trustees. The benefits can be provided through the purchase of insurance or otherwise. We are unaware, however, of any county that has formed a health insurance consortium under Article 44. This may be due to confusion about whether Article 44 health instance consortiums are subject to community rating. The Albany County consultant report cites a December 28, 2004 opinion of the Insurance Department’s Office of General Counsel exempting a Taft-Hartley Fund from the small group rules. However, the language of the opinion implies that other trusts established under collective bargaining agreements may qualify.

Both the Albany and Schenectady County Shared Services reports made suggestions regarding policy changes that could make it easier for municipalities to form health insurance consortia. These include:

The state Department of Financial Services should work with local governments to find ways to streamline its current regulations and provide technical assistance so that it is easier for counties to form municipal health insurance consortia and reduce health insurance costs for its municipalities and school districts.

Identified as a problem by Cattaraugus, Hamilton, Madison, Ontario, Wayne, Westchester, and Yates counties, many local governments believe that New York State is restrictive and prescriptive about how the consolidation of justice courts are to be handled.

For the dissolution of a village court, the village must pass a resolution or local law indicating the intent to dissolve into a town court, subject to permissive referendum of village residents. This dissolution can only take effect upon the expiration of the current justices’ term.

Town courts may consolidate per NYS Uniform Justice Court Act Section 106-b. The legislature authorizes multiple towns to elect a single justice to preside in the justice courts of two or more adjacent towns within the same county. The Cattaraugus County Shared Services plan explains the process as follows:

The process of electing a single justice would begin with each town enacting a joint resolution agreeing to undertake a study of this idea. This resolution must be filed with the town clerk of each of the participating towns. Once this occurs, a study may begin. Within 30 days after the study is completed, each town must publish a notice in its official paper notifying the public that a study has been completed, and shall set a time for a Public Hearing on the results of the study. This hearing must be completed no less than 20 to no more than 30 days after the publication of the notice and the Public Hearing.

Within 60 days following the last public hearing, the town boards of each town must decide whether or not they will participate in the joint plan to elect a single justice. If two or more adjacent towns do not approve the plan, the process is then terminated. If the plan is approved by two or more adjacent towns, each board that approves must adopt another resolution. This resolution should call for 1) election of a single justice to preside over the courts, 2) abolition of the existing office(s) of Town Justice in each of the participating towns and 3) the election of a single Town Justice every fourth year thereafter.

Once the joint resolution has been passed, a resolution must then be forwarded to the State Legislature as a “home rule message”. The State Legislature will then have to enact legislation implementing the plan. The shared justice would have jurisdiction in each of the participating towns. The shared justice would be required to keep separate books, dockets and records for each Justice Court, as well as a separate bank account for each. Revenue would continue to be allocated to each participating Town. (UCJA-IO6-b) The State imposed process to achieve consolidation is deliberate, detailed and cumbersome, it is not amenable to quick implementation. It is also expected the State requirements for maintaining records by municipality may be problematic.

In order for a town to reduce the number of its justices it is subject to permissive referendum as provided by New York State Town Law Article 7, Section 90 through Section 94. In addition, the current options and flexibility offered in Section 106a and Section 106b of the Uniform Justice Court Act lacks the flexibility to deal with two or three towns, when they start out with different numbers of justices. For example, Hamilton County is made up of six towns with two justices and three towns that each have one justice and they have found it difficult to consolidate their town courts due to the restrictions in Section 106a and Section 106b of the Uniform Justice Court Act. The Yates County Shared Services Plan cites the problem of justice court consolidation into a “district” court that occurs when two of the county’s villages are divided among multiple towns, each of which might or might not choose to participate in a district court. They believe that state legislation is needed to ease this and other barriers to establishment of a “district” court. Ontario County cited operational and security mandates that increase expenditures relating to the court system including staffing, access control, and the inability to use court facilities for other municipal operations like committee meetings, boards, and community access.

Under current state education law shared services purchased from a county are not eligible for state education aid reimbursement. This was identified as a problem by Albany, Chautauqua and Onondaga counties. There was support to have the state and counties work together to allow shared services purchased from a county to be eligible for reimbursement (just as it is for BOCES) as long as the shared service is for the same or lower cost than the cost available from BOCES. School districts cannot obtain power from solar facilities located outside school district boundaries. This makes it difficult for school districts in urban areas to take advantage of solar power. It also makes it impossible for solar collaborations between neighboring school districts and municipalities when economy of scale can result in greater energy cost savings.

Currently Section 8 of the 1950 Education Law does not allow Big Five school districts to participate in cooperative purchasing with BOCES across New York State. It should be amended to allow Big Five school districts to engage in shared bids or piggybacking on BOCES contracts.

Real Property Tax Law only allows for a one year contract between the towns and county for assessing duties. The law should be changed to allow for a town to dissolve their assessing function if both parties agree. This was identified as a problem by Cattaraugus County. This is similar to when the villages dissolved their assessing. If this is not done, then it would be a disaster if towns buy-in to having the county do their assessments and then drop out down the road. To insure workflow and quality services there needs to be a change in state statutes to allow for, and even endorse, this option.

Given the current low-interest rate environment, there was an idea to allow the county to offer municipalities an option to consolidate and pool debt. While some municipalities have refinanced and consolidated their debt on their own, lowering interest rates, and therefore overall annual costs, during the process, Albany County floated an idea to pool all municipal debt at a lower rate. However, upon working with the county’s bond counsel, it was raised that consolidating debt for municipalities is prohibited. Therefore, the state should work with municipalities to determine the legal impediments and clear a way to give counties more flexibility to pool and refinance local debt.

This was identified as a problem by Hamilton County. Hamilton County is working with the Town of Inlet and the town of Webb in Herkimer County to allow for one shared police force. This opportunity to combine the Inlet and Webb Police Departments makes fiscal sense and will provide better law enforcement coverage. In order to accomplish this shared services project state legislation is needed but the local governments were unable to obtain legislative approval in 2017.

The first round of the CWSSI program has yielded taxpayer savings, efficiencies, and better coordination among local governments across the state. Many plans submitted highlighted that there were many shared service efforts already underway, yet overall not only did the CWSSI yield additional taxpayer savings, it more importantly created an infrastructure for better coordination and cooperation among local governments.

As county shared services panels move into the implementation phase or complete and adopt plans next year, the following are findings based on our review of the program to date:

There was great variation among the plans, including how they arrived at cost estimates — and the reporting itself. For example, plans such as Franklin and Westchester Counties did not describe how they achieved the savings, while Cattaraugus County explained their estimates with great specificity.

Remaining plans due next year should include a clear description of goals and a specification of the goals in terms of each of the stakeholders. Moreover, detailed analysis of the proposed project is needed in terms of key stakeholder. Questions to be answered, such as: Does the enabling policy framework exist? How will the work processes be redesigned to be interoperable across boundaries? Who are the responsible parties and what role will each play in planning and execution of the shared service?

Other details such as milestones, expected challenges and potential solutions, and workflow and timelines characterize leading plans. Finally, clear and specific methodology for determining the cost and the savings estimates, as well as a list of underlying assumptions related to the plan should be included.

Many of the shared service panels included additional work and future issues beyond the scope of the CWSSI process. There were a number of examples including Albany, Ontario, Rensselaer, and Yates counties. Although Yates County was unable to adopt a plan with any savings in the first year, they were explicit in saying they would continue to work together. “The Panel recognized the value of the process and the identification of possible opportunities for efficiency and cost reduction….Through the Readiness Initiative, the Panel will in the future continue the work initiated under the Shared Services process and continue its pursuit of further options for service consolidation and cost reduction” (Yates County Shared Services Plan). Likewise, Jefferson County stated in its plan that “many on the Panel have decided to continue informally reviewing a series of other potential shared services that have already been identified.”

The success of shared services is based in large part on the success of the shared governance put in place to design, manage, and monitor the shared service implementation. Many county plans made no mention of the governance structures necessary to ensure that shared service is managed through an open, well-defined, and effective shared resource. The identification of what decisions will be made and by who is critical for ensuring the long-term success of the shared service.

Overall, the initiatives presented within the plans require to a great extent the creation of new ways of working and of working together. Whether counties and municipalities are engaging in shared services or managed services, some level of change is required of all those providing, requesting, and receiving services. It may be fair to assume that some counties and municipalities who have already been successful in creating complex shared services arrangements understand the upfront investment needed to identify the depth and the nature of the changes and investments required and to create the necessary capability to make and sustain those changes. Those who have created successful managed services arrangements may be less experienced in the deep and thorough analysis and change management that will be required to create a fully functional and value generating shared service. Even the simplest shared services projects will require new levels of knowledge and information sharing such as providing shared access to data and creating joint scheduling systems for shared resources, among others. Variations in the level of understanding that shared services requires new ways or working and will not generate envisioned savings if systems are put in place that replicate how work has always be done.

Our review found that many officials on the panel thought the core process of working together was helpful, especially as new issues emerged — technology issues, new policies that had to be implemented, and the like. In addition, many of the proposals raised in the plans submitted will be over multiple years and take an ongoing concerted effort among municipalities.

Therefore, we recommend that counties formalize and make permanent a shared services panel. One model adopted by Onondaga County was to use state General Municipal Law section 239-n, which authorizes the creation of intergovernmental relations councils. The purpose of the law is “to strengthen local governments and to promote efficient and economical provision of local governmental services within or by such participating municipalities.” The state law authorizes this council — which is made up of the local governments within counties — to make recommendations of additional efficiencies, operate as a purchasing consortium, and hire staff and create by-laws.

In addition, there are other ways to create a more formalized arrangement, like under section 239-n of the General Municipal Law, which are found under some county charters. For instance, the Ulster County Charter has a provision for Intermunicipal Collaboration, which has yet to be implemented (see ARTICLE XXXVII of the Ulster County Charter).

There are many laws, regulations, and policies in place at the state and local level that make commonsense shared services and efficiencies more difficult. For example, as was mentioned in the barriers to shared services sections, there were examples where motivated school districts and municipalities ran into regulatory walls, like school districts inability to build solar panels outside their district lines. In many cases, there was confusion about whether there was an actual legal prohibition, whether the problem was regulatory, or simply policy. Case in point, there was confusion around the creation of health consortia. Already a complicated undertaking for local governments, the process could be eased by a clear line of communication between local governments and state agencies to eliminate unnecessary and antiquated laws, rules, and regulations, as well as speed the process of implementing shared services.

In other cases, some of the more impactful shared services ideas, like health and other insurance consortia, energy efficiency (like LED lighting and solar installations), and government consolidations, require more technical policy, financial, and other expertise that some of the smaller municipalities do not have. Therefore, the state and local governments should develop a formal regulatory and technical assistance working group to break down barriers to shared services.

As mentioned above, we believe the CWSSI process should be made permanent through the permanent creation of shared service panels. If that is implemented, the state should create new financial incentives or align the existing financial incentives offered for shared services and government efficiencies to the panels to spur ongoing work.

The state’s one-time match is a great start. However, some counties believe the shared services law creating the 2017 process provides financial disincentives to municipalities to complete the plan this year since the law only allows the state match for savings achieved in year one of their plan. All counties that did not submit a plan in 2017 either explicitly or implicitly stated a major reason for not submitting their plan was to maximize state matching funds in 2019.

In addition, many of the proposals included in the submitted plans were contingent on receiving existing state funding, like four of the six shared services proposals described in Ulster County that are contingent on winning the state Municipal Consolidation and Efficiency competition.

Realigning or additional financial “carrots” were raised in various plans. Ontario County observed in its shared services plan that the state should consider permanent incentives for inter-county cooperation and dialogue and regionalization of continuing services that result in reduced property taxes. Similarly, the Tompkins County plan states that the state should incentivize large-scale shared services activities through the provision of grant funds offered through the NYS Department of State or other agencies:

If these panels are made permanent, it will take additional financial realignment to fund their activities and make them successful—especially the larger and more complex proposals. Therefore, the state should realign existing financial incentives or create new financial incentives for any panel made permanent by a county.

Even with the guidance provided by the state, many of the plans greatly varied in terms of how they analyzed proposals and reported their findings. Not only was that not in compliance with the requirements under the law, it made it difficult to compare to other plans. Counties, like Franklin, had “tbd” or no information provided in some parts of their plan. The format of the plans were also varied, making an apples-to-apples comparison impossible. Therefore, the state should work with the panels to develop a common template on reporting information.

Simply because the chief executive officer of the county chaired the panels did not mean that the counties were best suited to provide all the services. In many cases, it was not the county, but towns, cities, and villages that had the expertise and equipment to share — so the services does not always have to come from the county itself. For example, in the Albany County plan, the county will coordinate shared personnel services, but the local municipalities would share the needed personnel to one another. The critical factor was a centralized process to organize efforts, but the better plans used the strengths of all of their local governments to share services and find greater efficiencies.

Some counties, like Sullivan noted it was “unfair” that schools were not required to participate. However, the law allowed the panels to include school districts—it was up to the county. Nine counties, included school districts in the process. In many cases, it was simply a matter of leadership by the chief executive officer of the county. Because school districts use BOCES, they have expertise to offer in shared services generally. But, more importantly, many ideas for savings and better service came up among local governments and school districts that would not otherwise have been adopted unless they were included.

Every shared service has some aspect of technology are a core element. The shared service plans put forth appear to fall into two general categories: (1) IT as the focus. These include initiatives that specifically state that a project that is or relies on IT and (2) IT as an enabler. These include initiatives those focused on a new cooperation, sharing of resources, consortia, among others.

Of the plans that present new technology as the main focus of the shared service, the tendency is to focus on the new technology versus the business goals and what is involved in realizing those business goals. Emphasis is placed on the availability of new systems rather than the system as an enabler for a business process. Lack of attention to the business processes and the overarching service delivery goals of the shared service increases risk and cost, leading often to failure of the system to deliver any particular public value. In order to mitigate that risk, the 80/20 rule applies here. Eighty percent of the work associated with a public sector innovation should be focused on the upfront work; identifying the desired goals, requirements, interdependencies, agreements, and necessary modifications to current policies and processes. If the “before the beginning” work is completed, the implementation typically requires only 20 percent of the overall effort. Conversely, if there is no time spent at the beginning and there is a rush to a solution, technological or otherwise, then implementation is high risk and prone to failure.